When Charles Portis died last month, Rebecca Bengal urged me to read his essay Motel Life, Lower Reaches. I replied by suggesting we devote a newsletter to the theme of motels. One month later we’re in a state of emergency and the subject sounds a little trivial. But as we come to terms with the implications of ‘social distancing,’ maybe there’s something to be learned from reflecting on our creative attraction to these lonely rooms. If nothing else, it’s something to pass the time in quarantine. In that spirit, I’ve also recorded another episode of the The Little Brown Mushroom Podcast. You can listen to me read Brad Zellar’s book, House of Coates, in its entirety HERE.

In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: Self Portrait by Cynthia Cruz

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: “I Dyed My Hair in a Motel Void”

- Dear Lester: Should I move back? Nature vs. Nurture?

- Ex-Libris: 24 Pieces by Allen Ruppersberg

- Recently Received: Oobanken by Jerome Ming

- The Lunch Table

Picture & Poem:

I know it’s a cliché, but hotels energize my creative process like nowhere else. If photography is a place for me to simultaneously go out into the world and dive deep into myself, hotels are my creative headquarters. I sometimes think of my time spent in hotels as a kind of unseen performance art. Every once in a while, usually while drunk, I document this performance. In Tokyo I not only photographed myself drinking whiskey, I made a video of myself taking the picture. An artist in Italy recently sent me a drawing he made of this photograph. My ego was sufficiently stroked, but what value can my navel gazing have for others?

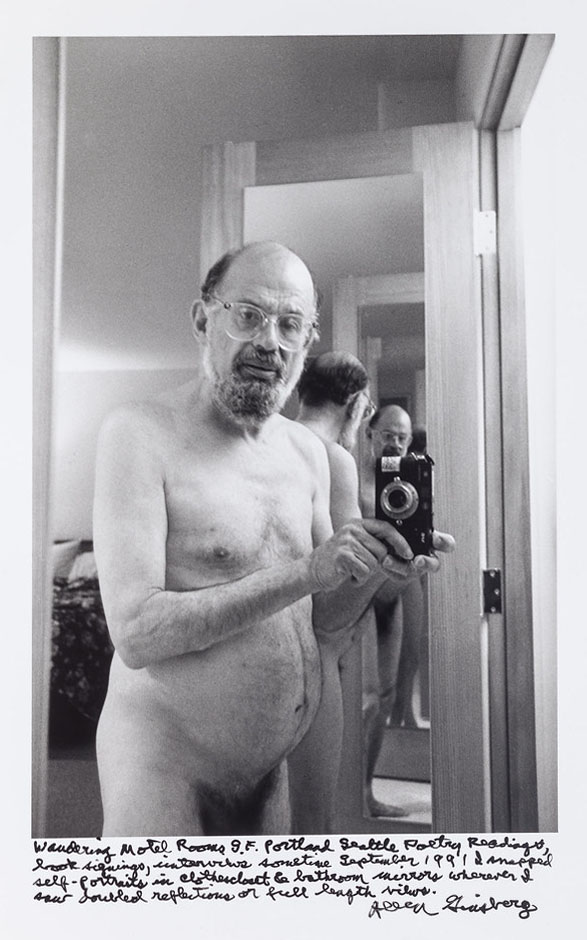

I thought about this question while reading the poetry of Cynthia Cruz. Cruz is a writer who is willing to ruthlessly look at herself in lonesome mirrors. She has numerous poems titled “Self-Portrait” and even more located in hotels. As with the photo of a 65-year-old Allen Ginsberg reflected in an anonymous motel mirror, Cruz’s lonely poetry makes me feel less alone.

SELF PORTRAIT

By Cynthia Cruz

Black and white photographs

torn from the pages of magazines

from the 1970s. And stacks of books

and artifacts on movement theory

and the work of the post-conceptual

artists of the former Eastern bloc.

Small, seemingly mundane actions

such as the washing of one’s own face,

in the isolation of one’s own home

do, in fact, count as an act of art.

Or, rather, as a valid means of protest.

In a society in which the state is everywhere

and sees all. In a culture in which

everything is swallowed and then

refashioned, what constitutes as nourishment

For three years I traveled from city

to city, at work on a performance

piece titled, “Hotel Rooms” in which

I lived for one month increments

in Warsaw, Bratislava, and Belgrade.

Containment is often detrimental.

And I have spent my life trying

in as many ways as I could

to escape it. But some type of containment

is needed. Genet was happiest in prison

and it was there with the other men

that he could love entirely, be

who he was without terror

of exposure, and yet remaining

always on the periphery. In the hotel rooms,

I photographed myself

performing small gestures such as

the act of drinking tea or the ritual

of smearing rose water on the face

when waking, after a bath.

In the embrace of isolation

and the reduction of artistic means,

in that small and nearly silent

opening, that minute movement—

it is there, in that increment,

where, finally, the promise

of a new language will appear.

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal:

“I Dyed My Hair in a Motel Void”

Sure, Cormac McCarthy allegedly received word of his MacArthur Grant while living in a motel in Knoxville, Tennessee, but few writers divined the precise virtues of the lowlife motel quite like Charles Portis, who populated his novels with just the grade of affordable and convenient dereliction to sustain his traveling characters in their inexplicable, obsessive quests. Ray Midge in Dog of the South makes it all the way to Belize from Arkansas, taking a room in the Fair Play Hotel sleeping in a bed with a headboard engraved KARL. Jimmy Burns in Gringos: “The towels are rough-dried in the sun. Very stiff and invigorating after a bath.” In his 2003 essay “Motel Life, Lower Reaches,” Portis mapped his own odyssey through the “rooms to let” era of which Roger Miller sang. He wrote of freckled mirrors and towels too short to use as a wraparound sarong while you shaved; in cesspool green swimming pools he detected a “Sargasso calm.” You get the sense that Portis simply wanted to sail through every lodge anonymously and yet, within Motel #3, “not quite a dump, at dump prices,” he quickly becomes a known commodity for a powerful set of jumper cables, bringing to life the sputtering cars in the lot. And then, not far from the town of Truth or Consequences, spooked by what is inexplicably too good a deal amid too unsettling a metaphor, he bolts—“the very carpet was clean. Motel carpet!”—bringing the whole excursion to a sudden halt.

A deeper meaning surely lay under that carpet that had long eluded me but I had come around to the thinking that maybe it had something to do with grace. Portis’ jumper cables hadn’t performed any good works in this place. He was paying exactly what the room seemed to be worth. And yet. The unease made him bolt immediately out of that room.

In mid-February, days after Portis’ death at 86, I sit sprawled out on very trustworthy motel carpet, mustard and orange and blue-gray, as if some enterprisingly thrifty person had stitched together a few samples from the 1970s and added a few coffee stains for authenticity. I am sifting through a shoebox of vintage matchbooks and keys with the plastic markers of their lodges and inns. A distant, perhaps no longer existent Howard Johnson’s. The Billy Mitchell Motel in Hatteras, North Carolina. Never mind how I got these things, that belongs to another story. The oceanfront studio efficiency in which I am sitting, let’s call it the Seascape, is a few grades above Portis’s favored bargains but it made me think of him instantly for it dates back to “Motel Life” era—built in the 50s, imitation Miami plunked at the north end of the boardwalk in Virginia Beach.

The motel I live in is not technically a motel anymore—no desk clerk, no housekeeping, all suites individually owned, though many of them rented out by the night, the week, the month. I am here temporarily, an off-season, long-term guest, a snowbird but one with a job. For now. A relief of Neptune and his trident juts out from one exterior wall, overlooking the wobbly blue pool. All along the patio people leave their curtains open at night. Two girls staying poolside listen to music on TV and Manic-Panic each others’ hair, one purple, one blue. I dyed my hair in a motel void is stuck in my head every time I see them after. I think of it as the motel where Shelley Duvall lives in 3 Women, minus all the yellow; The Karate Kid, my sister says when she visits, and she’s right.

In the basement, on a giveaway shelf of trashed beach reads, underneath a jubilantly forgotten textbook, I find a 90s-era postcard shot by the pilot of a beach-banner plane. It’s a picture of a family trying to secure their tent in the wind, faraway and overhead and slightly out of focus, just the kind of bad postcard photography I like. Over the years the Seascape has fallen apart and been redone again and restored to its imaginary mid-century glory. Ish. Portis would have been assured by the paint flecking off the outdoor railings and the dolphin emblem clock stuck at 4:18, the possum scurrying through the landscaping at night. The good looks of the room might have unnerved him, plus the fact that everything works, everything seems new—most everything that is, but the carpets.

Back in December as I’d prowled the sublet listings, I warmed quickly to the idea of a longer lease on motel life; a late-night Internet spiral led me here.

I arrive after nightfall on the first full moon of the new year. A man parks his bicycle and stretches out a sleeping bag at the end of the boardwalk, lined mostly with towering hotels, windows steaming from their heated pools. But most of the little guys, the actual motels as dated as mine, lock their doors, turn off their neon, and hibernate for winter.

*

He prowled the pool

Of the Holiday Inn

And felt a fit of uselessness

The sight of a pool

At midnight

In Texas

Poor Texas

Carved into

Like all the rest

3/79

San Marcos, Texas

Sam Shepard, Motel Chronicles

*

Of the motels that I’ve known, the ones that stick out are the dingiest. The rooms I’ve shared, the rooms I’ve slept in alone. The bad art, the plaid and flowered coverlets, the envelopes, the phones and the Bibles. The palm trees etched into the mirrors. The insistence of the streetlight flicker through every heavy drape, every louvered curtain. The smell of air conditioner leak in a Copacabana-themed room in roadside Pennsylvania. The perfect array of 70s catalog browns and tans and a tin ashtray inside the Thunderbird in Marfa before it got made over, where I had come alone almost all the way on a train to write. A few years ago I visited a motel run by a man named Tater to whom I am blood related in some realm of cousin. My grandmother and uncle waited in the truck as Tater and I talked through the glass. His was the ultimate no-tell motel: Decades and decades ago bootleggers, some also my relatives, hid in Tater’s rooms.

I remember at eleven, sliding into the middle of a sagging mattress I shared with my mother, when we were caught in a strange town overnight with very little money and me in surgery the next morning; I remember the voices all night near the dumpster by our Motel 6. Once I woke from a strange motel dream unsure whether it was something I was hearing. In a Best Western parking lot somewhere in Kentucky, cows stirred inside their trailer below me. At twenty-eight at a motel in Midtown Memphis all the attendants addressed me as Madam. When they delivered a light bulb to my room, it illuminated a large dark footprint on the wall which I preferred it infinitely to the Heartbreak Hotel, where I also stayed that trip. I have woken in plenty nicer places. Like Portis I never felt I belonged to them, much less deserved them.

*

Sometimes I drive the whole long shore route, where the motels thin out into mansions and cross the bay and become a motel strip again, up through the Eastern Shore and its off-season inns and KOA campgrounds. Even the side street motels, the Beach Carousel and the Cutty Sark and the MacThrift and the Royal Clipper, should be filling up about now, I’m told, opening up for spring. Robust demolition carries on—a biker sharp-turns into an abandoned gas station and cuts his engine to watch a wrecking ball attack the Neptune Park Motel. Off-season is its own little apocalypse—the ominous chandeliers in the closed windows, the gloom of gray fog on winter beach, the T-shirts in the souvenir stands showing the stale phrases of a summer ago, the palm trees on the lawns of the nearby mansions still wearing their winter blankets.

Among the books I had brought with me, anticipating the strangeness of my situation, possibly a different strangeness, were Motel Chronicles and Breaking and Entering, by Joy Williams, the story of Liberty and Willie, breaking into the second homes, the deserted mansions. This was the long vacation in a rented world. This was their life.

Back at the Seascape, hitched to one end of the motel is a restaurant, Eat, and its bar, Drink, Alice in Wonderland meets Repo Man. On one desolate, ice cold night that demands a margarita, a waiter eyeing his last check drop of the night spreads out a handful of locks on the bar, proceeds to pick them all. He tosses me his watch. Time me, he says.

Everyone I encounter around the Seascape I ask if they are year-rounders or, like me, just passing through. I meet Loretta and Geraldine, not their real names, sitting in plastic captain’s chairs by the startlingly blue pool. There’s water in it, but it, too, is closed for winter. We’re trying to play cards, Loretta says, though this wind. She slaps a palm over the base of her wobbling wine glass. I’m Loretta, and this is Geraldine. We’re just two friends whose marriages ended two decades ago and we just like to hang out and drink and eat and have fun.

Neither of us is trying to complete ourselves with a man, Geraldine says. Loretta owns one of the condos but she lets her son live in it. She still does his laundry. You should come out with us sometime, Loretta offers. Except we’re not going out anywhere anymore. I say, me neither, standing a good stretch of patio tiles away. It’s two days after three feet, and two days before six feet and three before ten.

Juanita has an upper corner studio, and two large-screen televisions inside it and a windowsill of poinsettias that partially conceals the view of the winos and skateboarders who loiter the boardwalk’s end as she goes to and from work. Delores has short white hair with one wide streak of gray and a sobering stare; her studio faces the ocean. She was lucky to buy when she did. Finally she wondered why she wasn’t just living here all the time. She quit her job and planted solar lights in the yard and put her cat Al, short for Alfonso, on a diet. It does not work. Al wanders in and out of the cat door onto a communal lawn bordered with imitation Adirondack chairs, loudly looking for love.

It’s not only women here. There’s Loretta’s son, and the guy with the barking miniature poodle who comes on weekends, and the on and off-again boyfriend who either belongs to the woman with the shabby chic balcony furniture or the woman with the lobster claw heart relief mounted above her sliding doors. There’s sunglasses-and-tan guy with the biceps poking out of his GOD IS DOPE T-shirt as he takes out the trash. The dad and his daughter, who, like me, uses the cuff of her hoodie to tip open the gate latch so she doesn’t have to touch it.

I don’t see the Manic Panic girls anymore. A hurricane suspension hangs in the air, a storm for which there is no eye and no rain and no predictable end. For there does exist a kind of us. We’re all decorated different, Delores says. No one is singing from our balconies but some are standing at attention, smoking furiously.

Are we year-rounders or just passing through? These days, if anyone asks, I will say I am another month and change. I will clear out when the true season begins, in summer, I say. I know I will try to get the coffee stains out of the motel carpet before then, even though they are not mine.

*

Far on the horizon container ships and cruise ships prowl along. South of the Seascape, in a mid-level room in the Oceanaire, a man stands in his underwear looking out at the silver sea, covered in the hot pink light of his room for which he must have packed his own bulbs.

Immediately north of us a new towering hotel busies itself for an opening that may not come for a long, long time. Lights on in the unslept-in rooms. The outdoor spa is the final touch. Since January a construction crew circles the grounds in fluorescent vests. Newly purchased palm trees lie in the scraggly pale actual grass on their sides, waiting to be planted alongside the strips of Astroturf—outdoor carpet. One day there is blue tile and the next water flows in the infinity pool and the PA system echoes all the way out to the wide, still mostly empty beach. All through the off season it is the provenance of just a few, belonging to the birds and the dogs and their people, the winter surfers, the hard luck metal detectors, few walkers and runners who sometimes go sideways against the wind, the one intrepid cat, the city trucks that come out to dump sand and drive over it, in endless Sisyphean strips and circles.

Sometimes when the construction workers leave, the music stays on, playing to the waves. The other day, it’s Stevie Wonder.When you believe in things/ That you don’t understand/ Then you suffer/ Superstition ain’t the way. In the shallows the dolphins swim along, south in the morning, back north before sunset. Lately they pause, jumping, darting through the waves, playing. They can’t hear it of course.

Dear Lester: Should I move back? Nature vs. Nurture?

Dear Lester: I grew up in the Upper Midwest, and left in my mid-twenties. I’ve been gone nearly ten years, with the last several in California. I do like the weather here, and I benefit from being around expressive people who balance my lack of expressiveness. Still, it’s expensive, and I’ve never been able to feel invested in a future here. I think about moving back to Minnesota often, but (in spite of myself) I worry that it’s not a step forward and that I would be settling for something safe. I keep delaying a decision. What are your thoughts on moving home? — Putting Off The Inevitable

Dear POTI: A few days ago, I spent time with a Holocaust survivor named Adam Han-Górski. You can learn about his childhood story here. He was born in Poland, moved to Israel, and then became a concert violinist who lived all over the world. In his early 30’s he was first chair of the Minnesota Orchestra. It was the swinging 70’s and Adam knew how to have fun. But in order to move up the musical ladder, Adam kept changing jobs until he eventually landed in Vienna. After he retired, Adam moved back to Minnesota. He said he came for the abundance of nature (“I can’t live in a concrete jungle”) and accessibility of culture, but I think his youthful experience played just as much of a role. “I was popular with the ladies,” he said.

As I was leaving Adam’s house, he showed me his collection of electric bikes, scooters and hoverboards. Watching him ride his all-terrain carving scooter in a non-descript cul-de-sec, I thought about how much life Adam was sucking out of Minnesota. What mattered most wasn’t the location, but his passion for life.

In mentioning your interest in moving, you mostly spoke in negative terms: the expensiveness of CA, the risk of “settling for something safe.” Before making such a move, I would work on your passion and let that positive energy be your guide. Wherever you go, there you are.

*

Dear Lester: My wife and I found out just a few months prior that we’re expecting in June. We have three dogs, live in New York City, and are both working artists. While we’re both excited (and nervous) at the thought of raising a child in New York, lately we’ve found ourselves reminiscing about our childhoods and the ways our parents raised us. The question of nature and nurture is always present. What makes a good parent? Are we unconsciously programmed to make the same intuitive decisions as our parents? What’s the first piece of artwork you remember seeing as a child? Best wishes, William

Dear William: Congratulations! Nature, nurture, tomayto, tomahto – forget about it. The process of parenting defies logic. After meeting Adam Han-Górski, he became one of my heroes. But what lesson am I supposed to take from this video of him talking about being raised by two different sets of parents in wartime Poland? The web of influence is too complex. It’s true that Adam’s birth mother was a musician and forced him to play violin. But Adam also told me that he never loved the instrument and always wanted to be a geologist. His simple, working-class adoptive parents were just as influential on his life.

As for myself, I have no memories of artwork from my childhood. Meanwhile my kids have been to countless museums and galleries and have little interest in art. Whenever I try to untangle these threads I’m just left with a bigger knot. Nature and nurture are too complex to analyze. You just have to go with the flow.

Do you need advice?

Creative or otherwise.

Email Lester: DearLester@LittleBrownMushroom.com

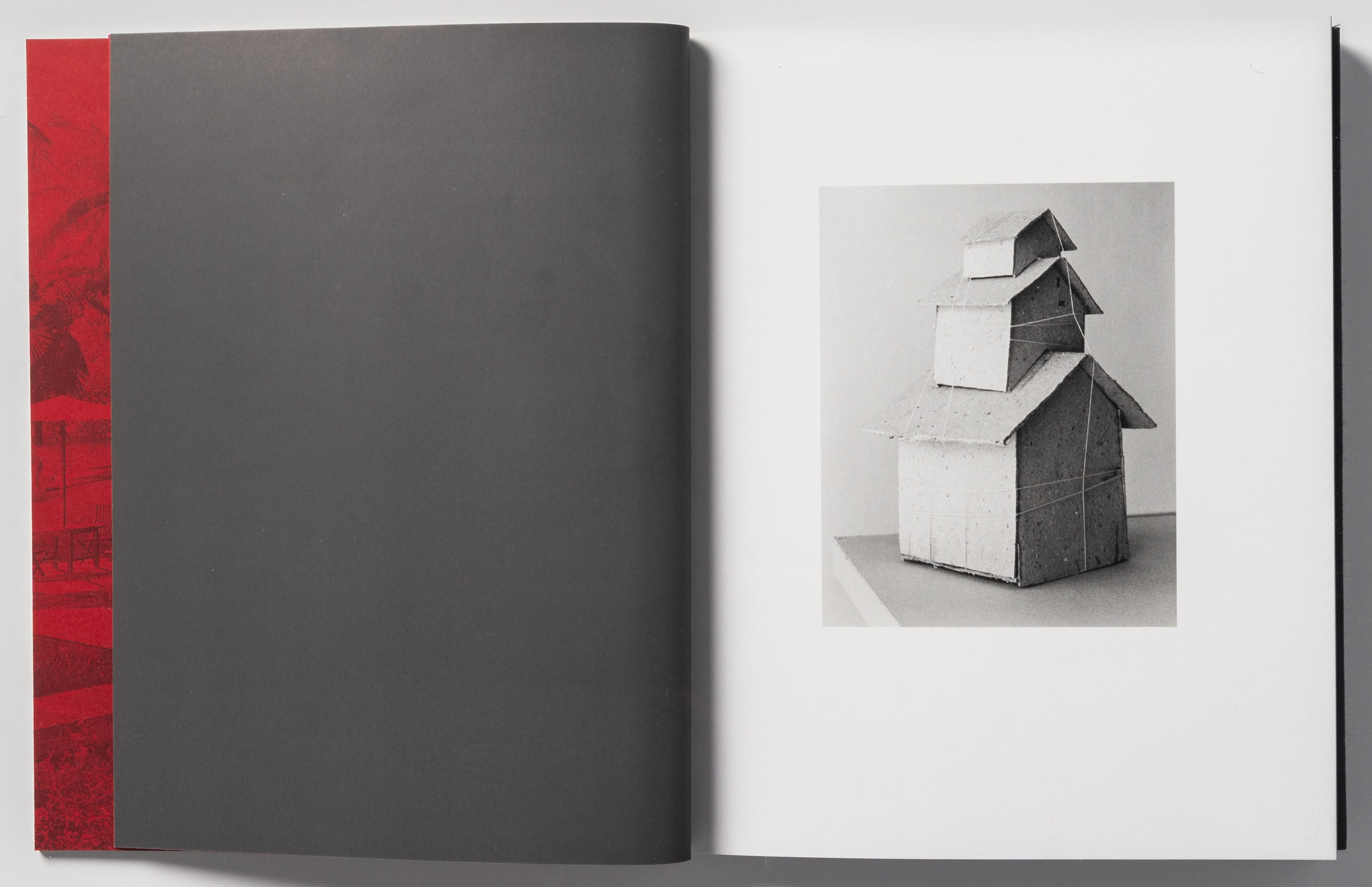

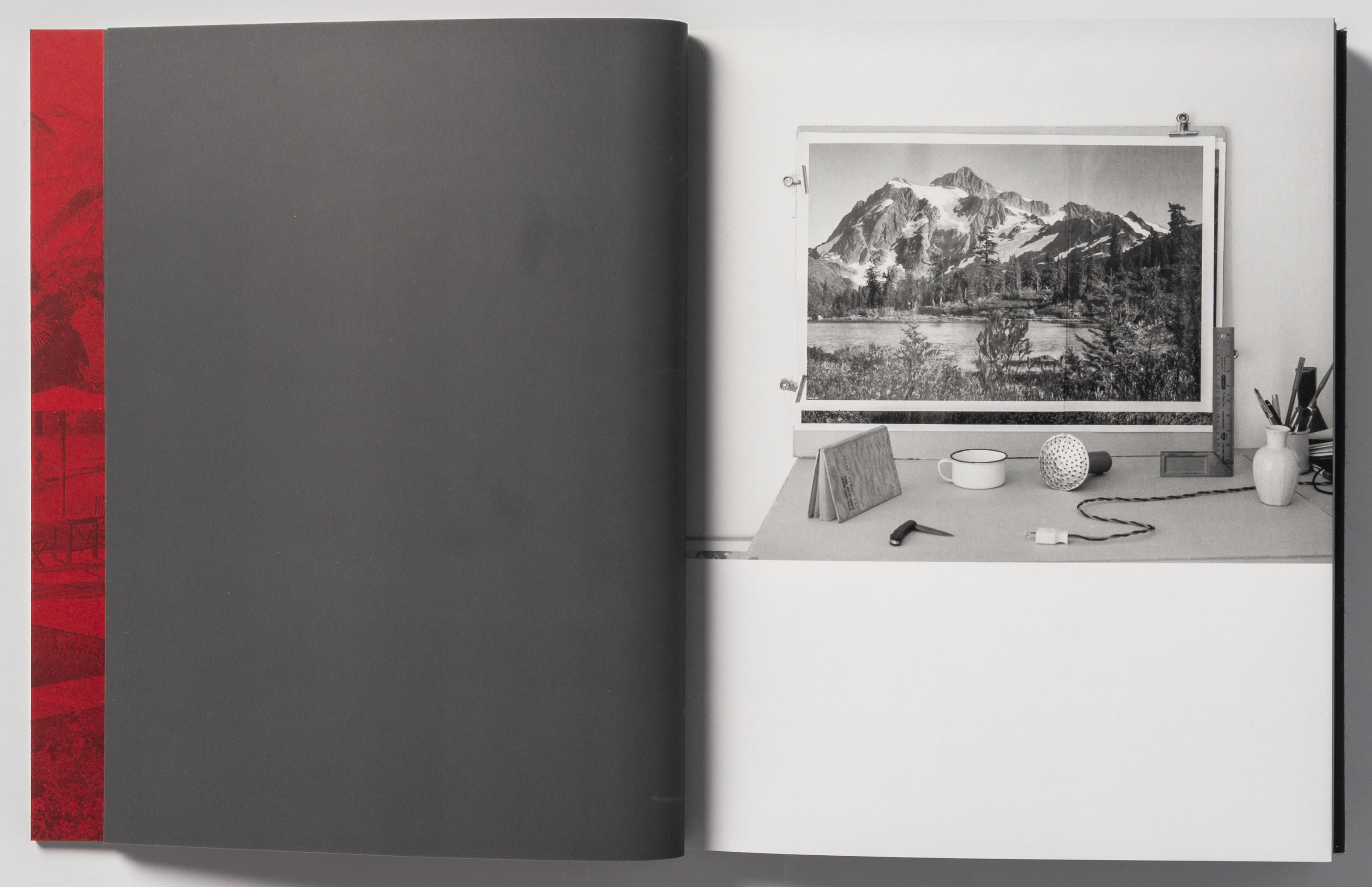

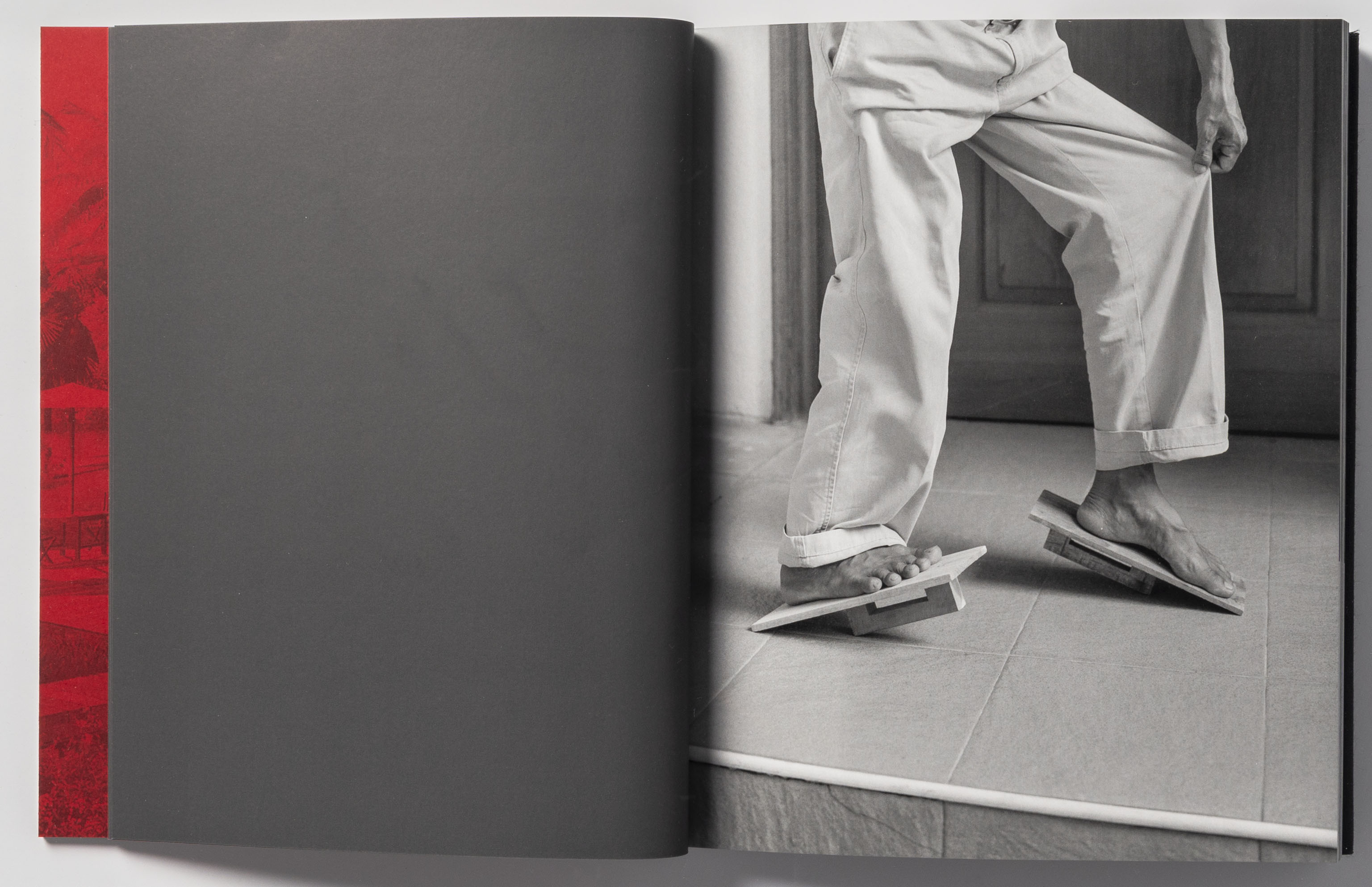

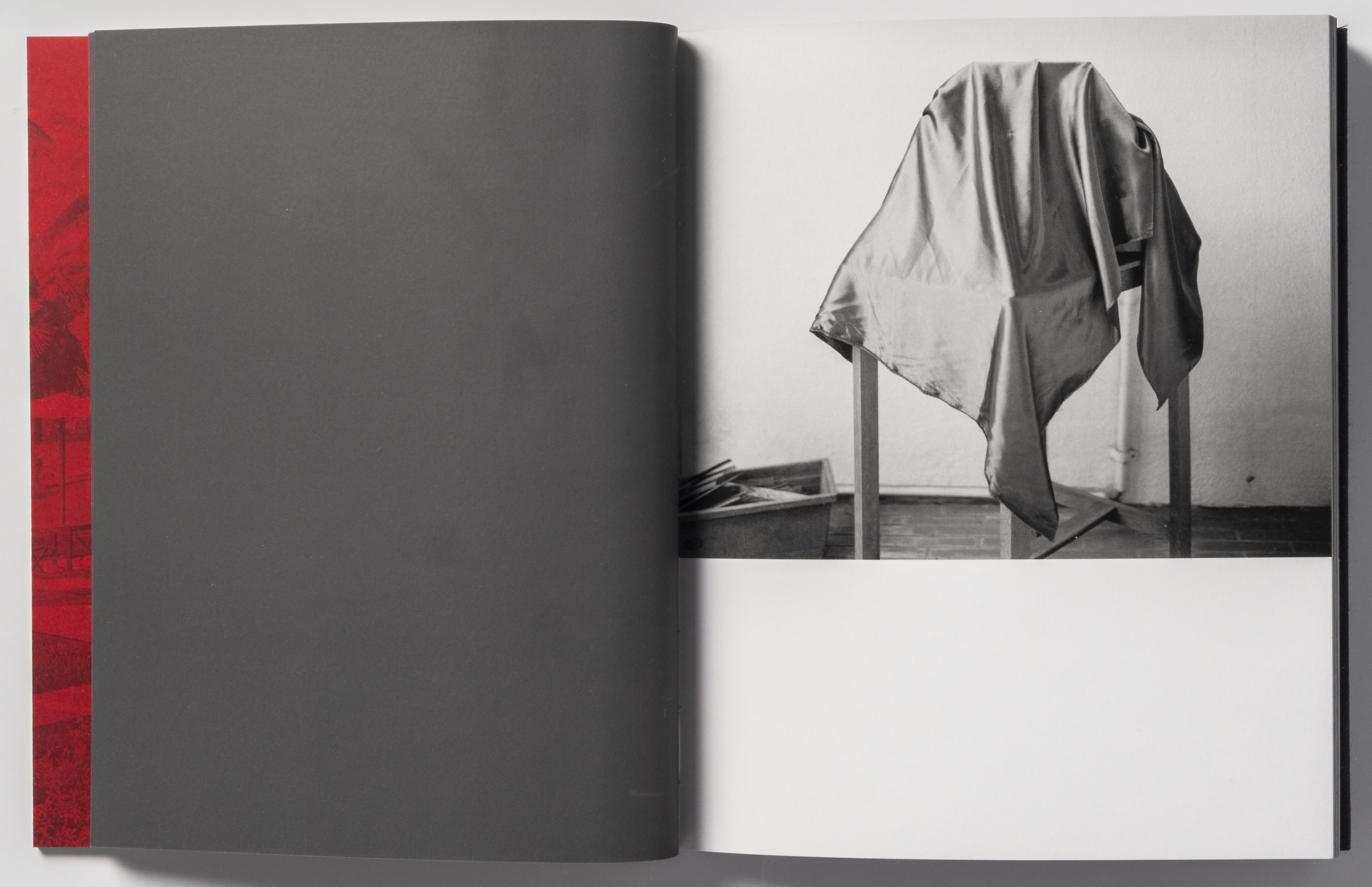

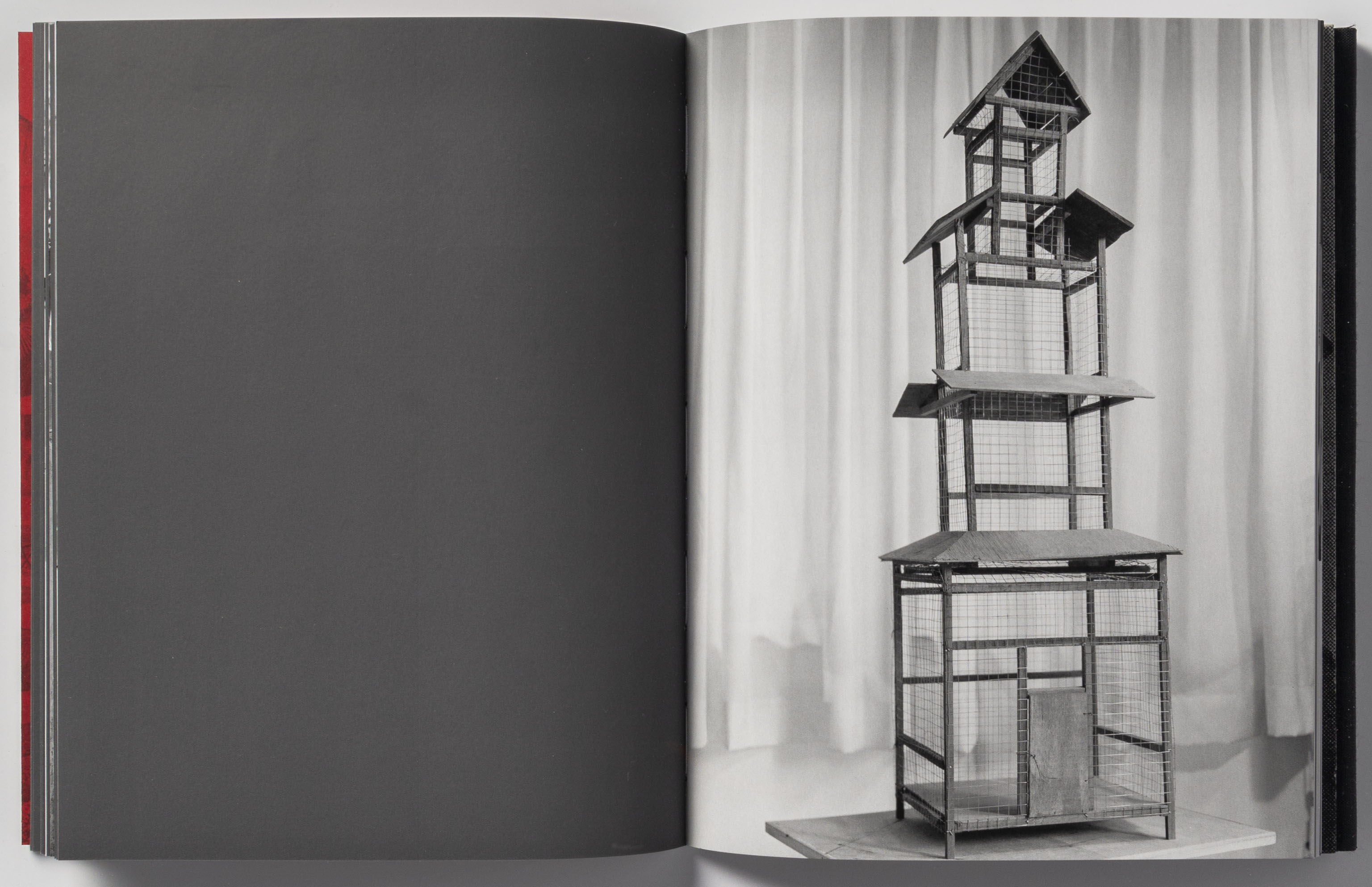

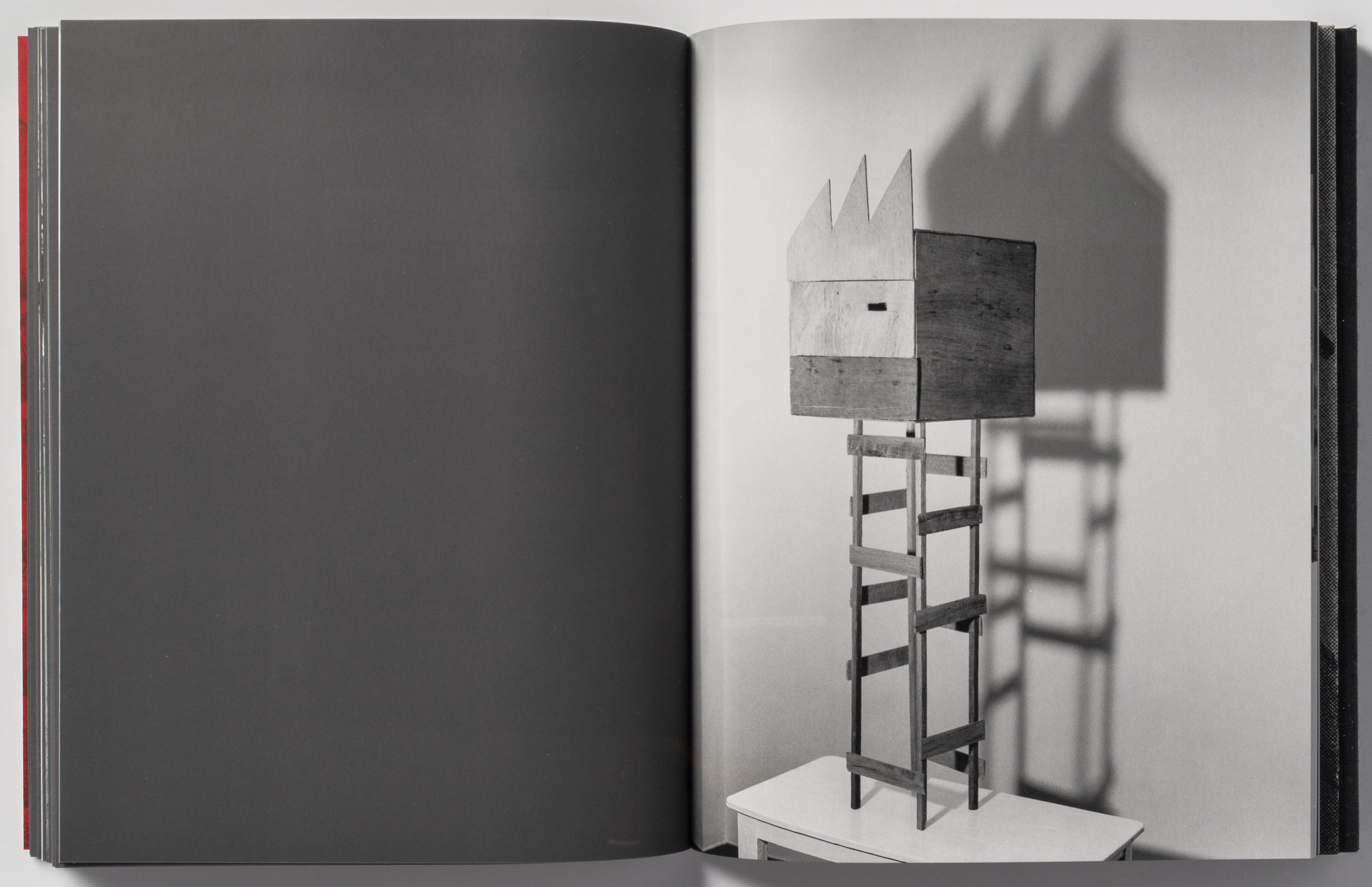

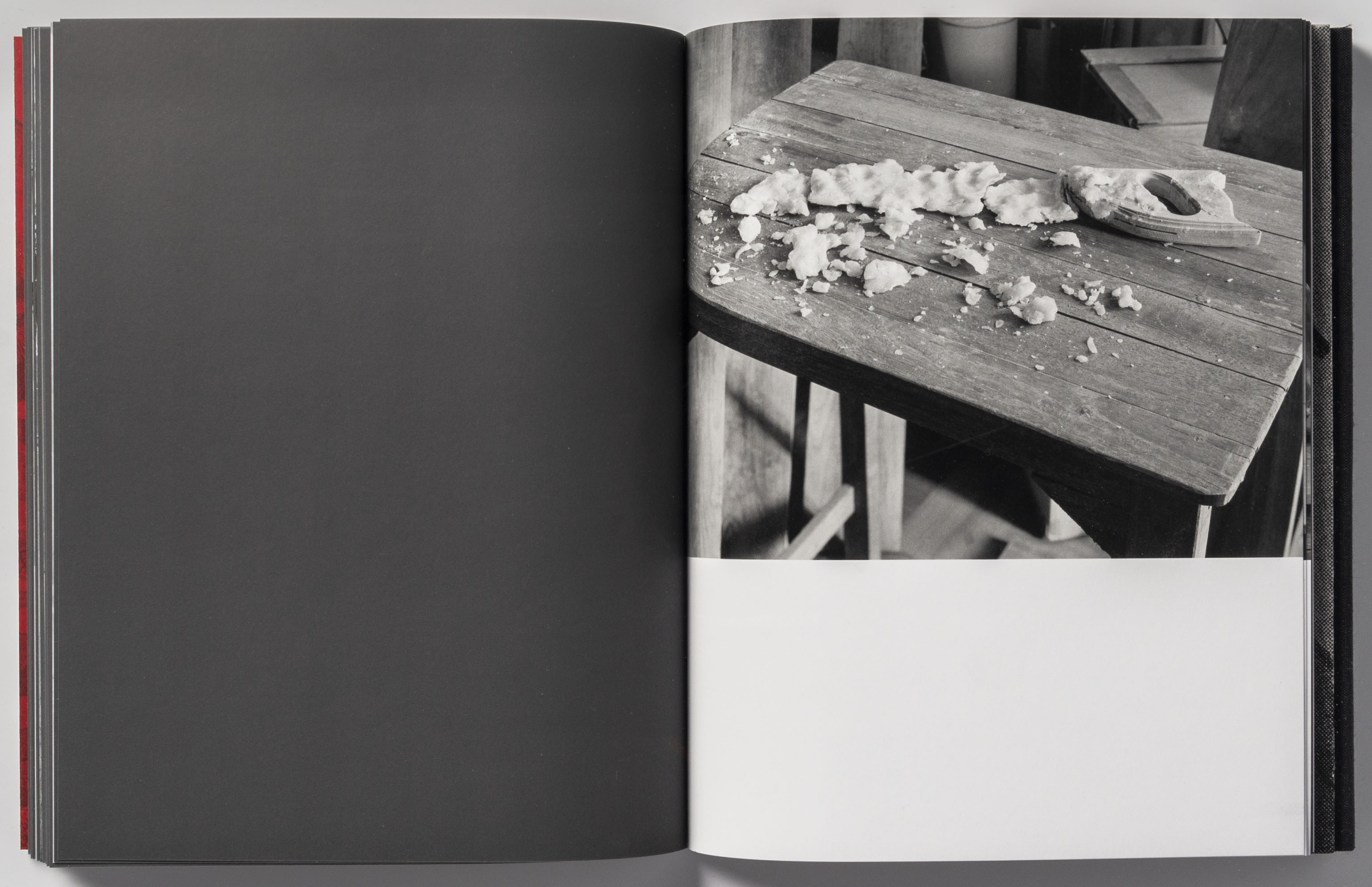

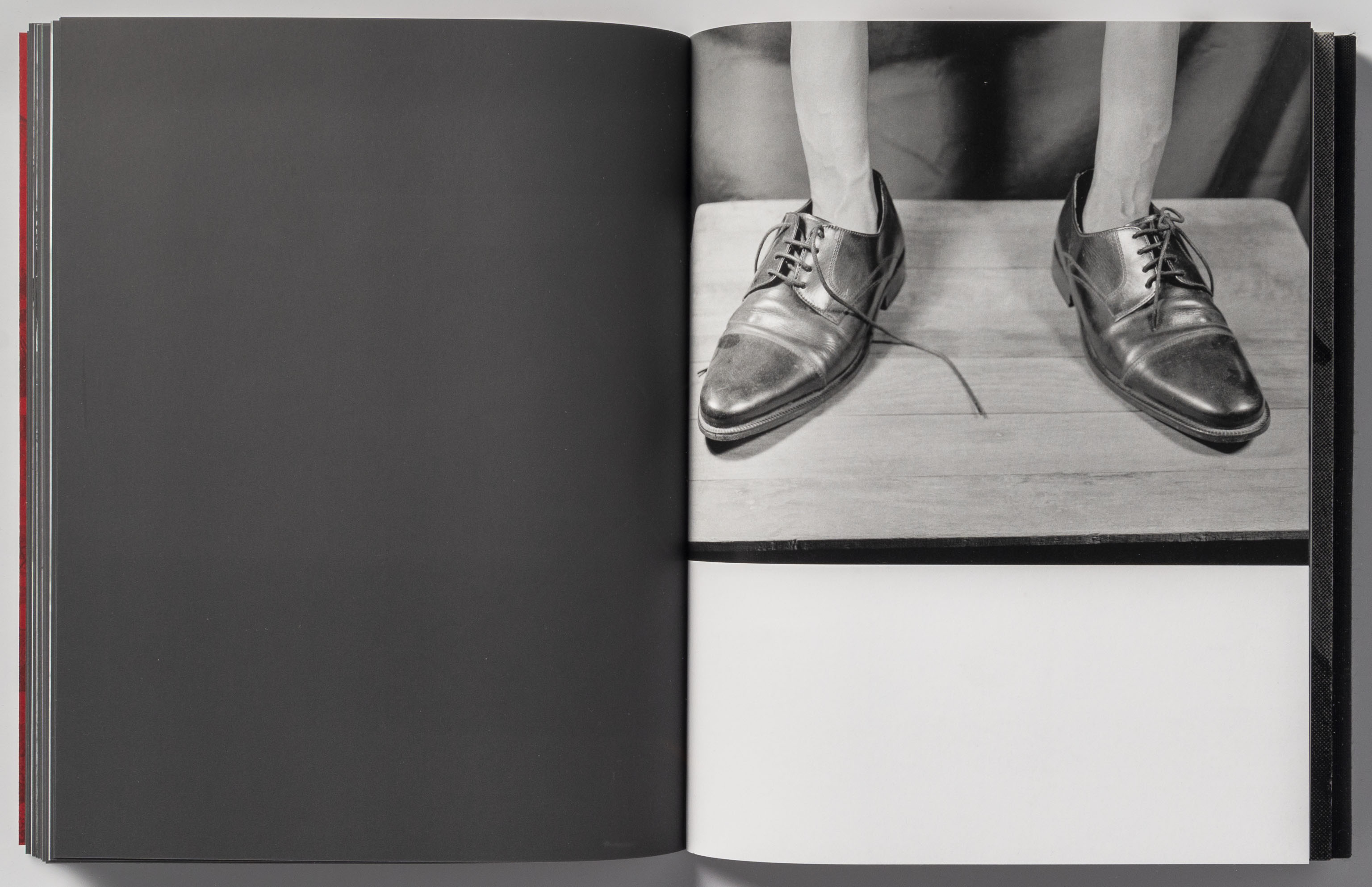

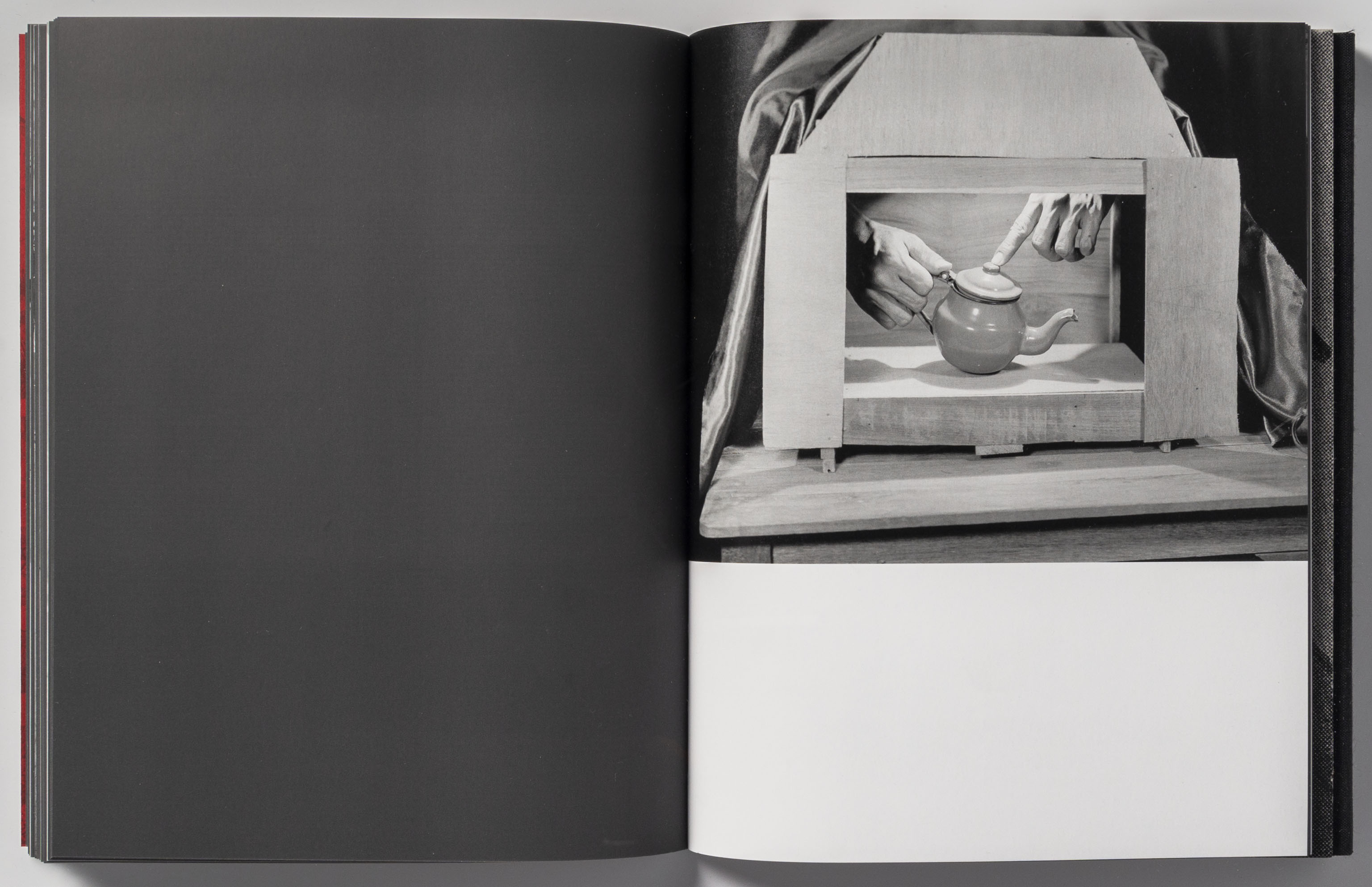

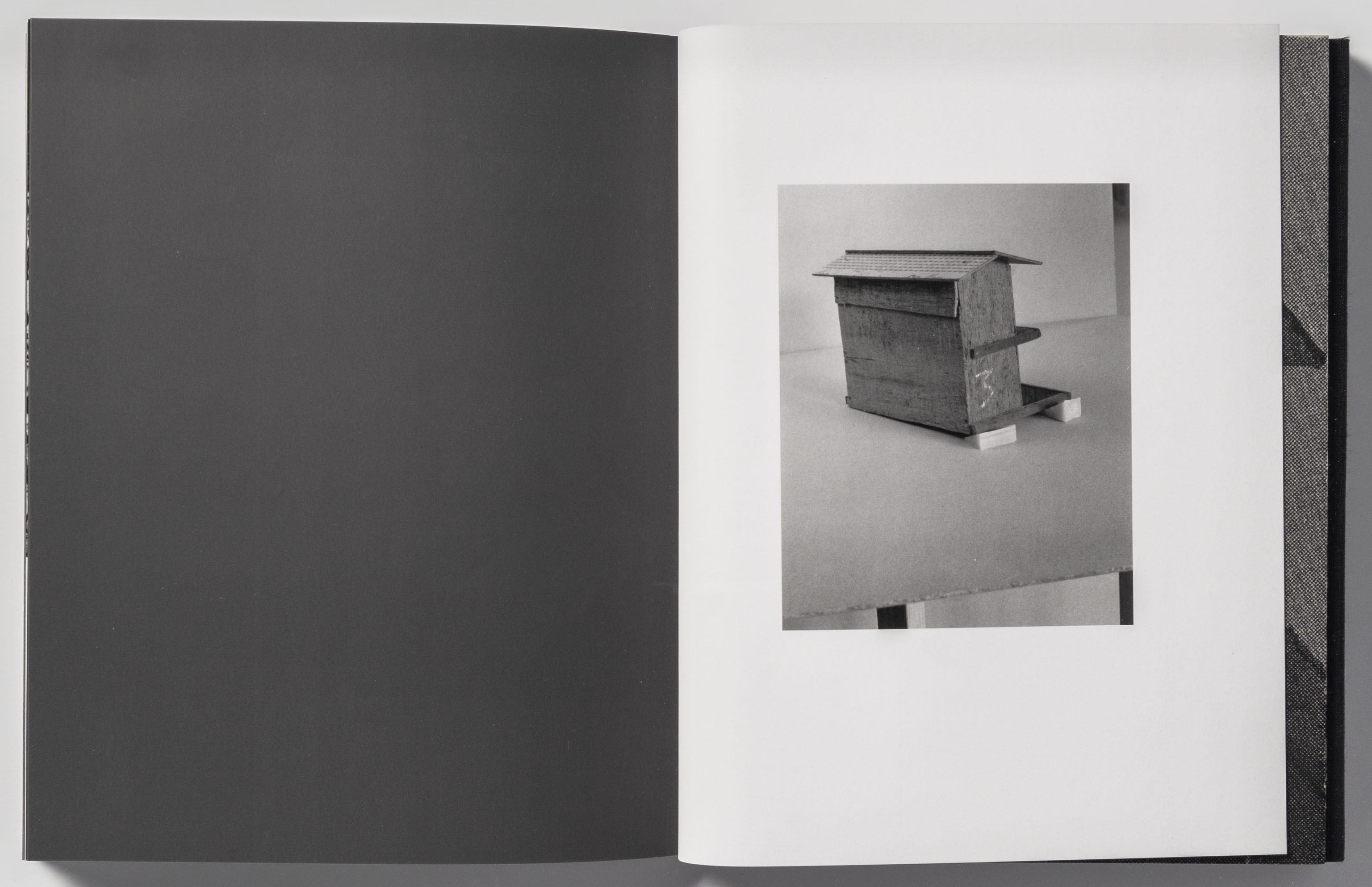

Ex-Libris: 24 Pieces by Allen Ruppersberg (1970)

I’ve often said that a book of photographs should have as many pictures as the photographer’s age. Allen Ruppersberg’s first three books, 23 Pieces (1969), 24 Pieces (1970) and 25 Pieces (photographed in 1971 but published in 2000), are the only books I know of that took this idea literally.

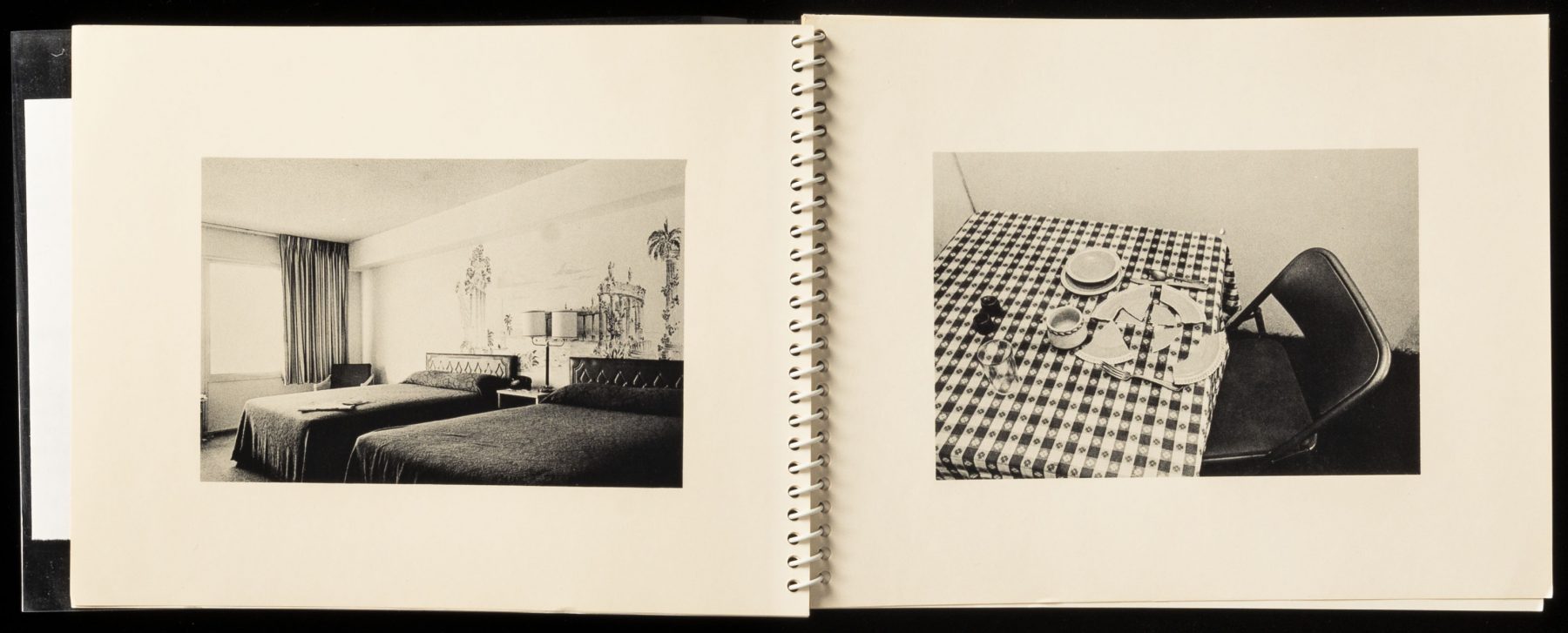

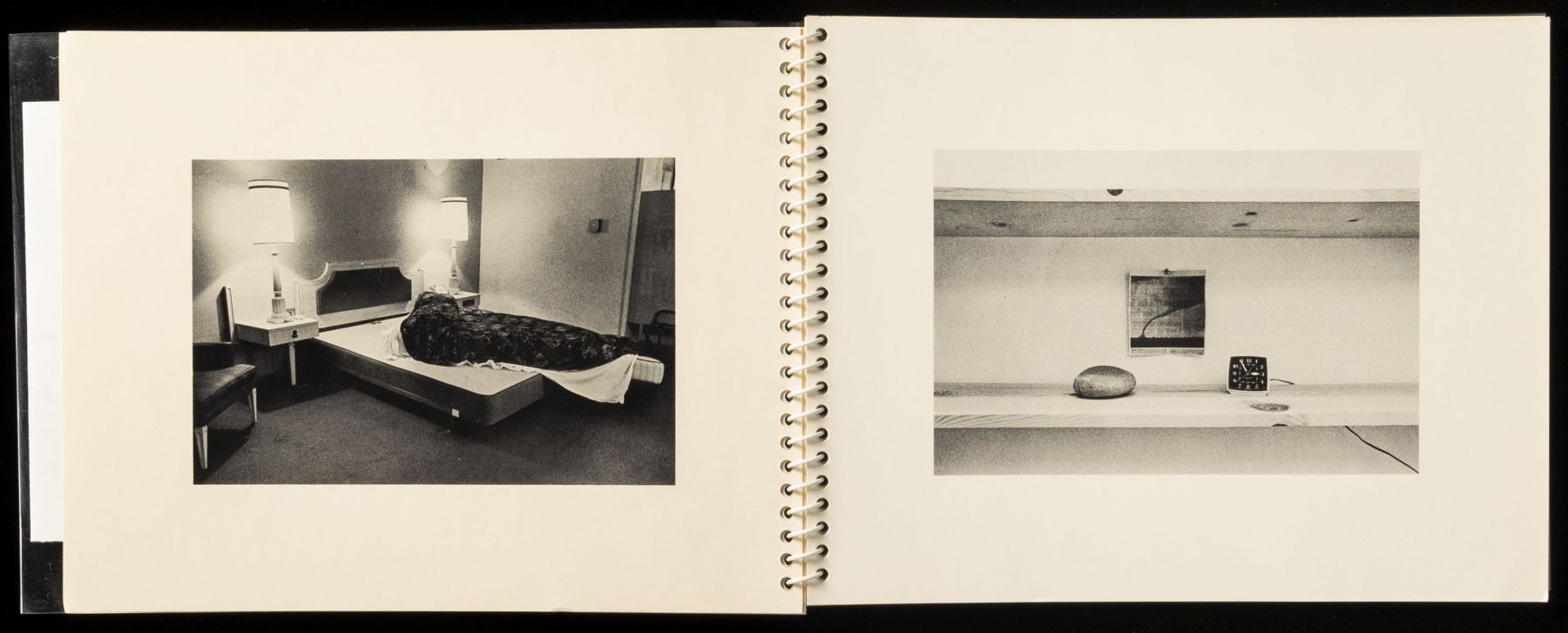

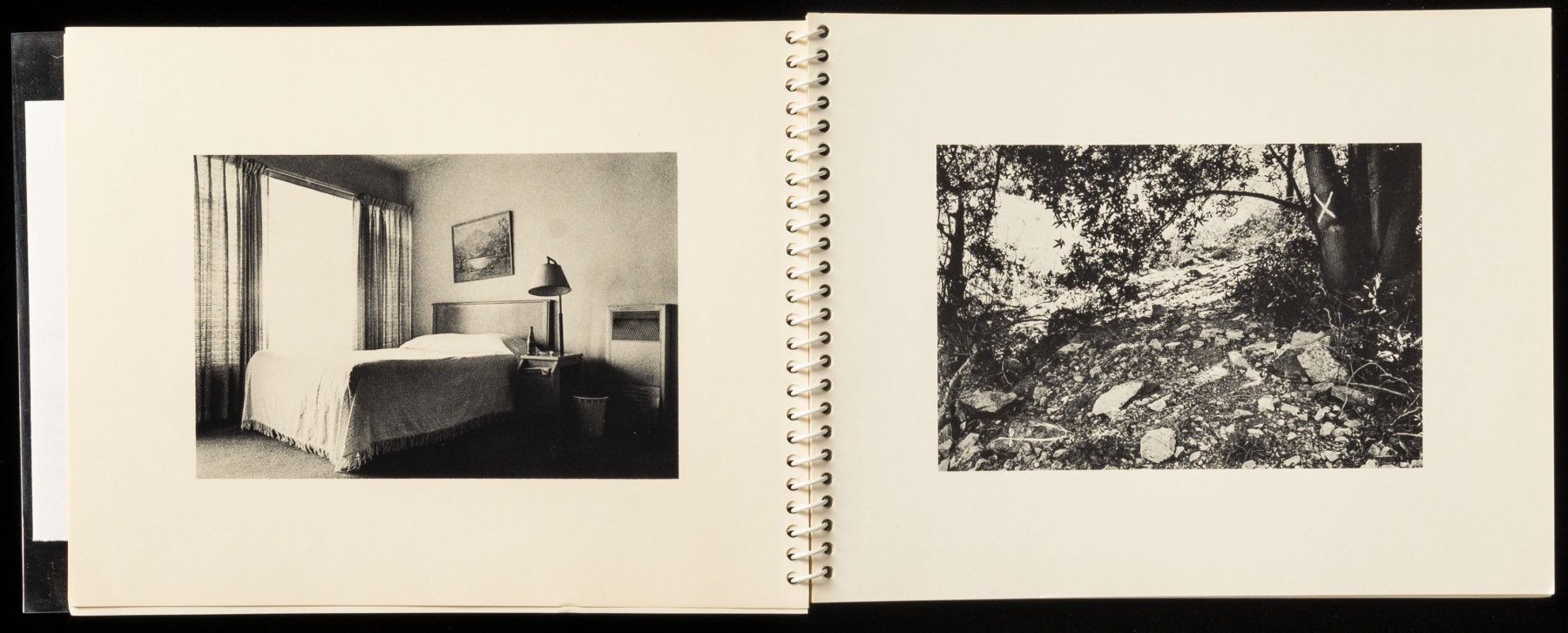

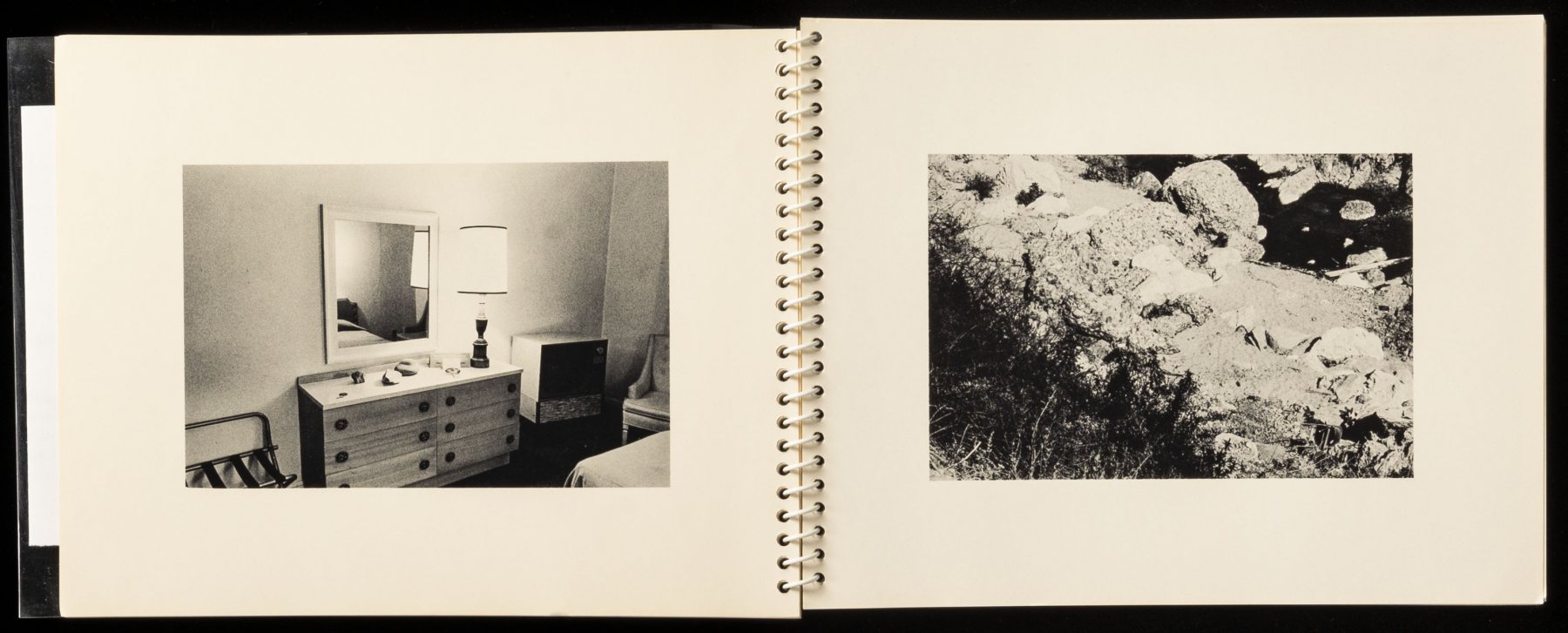

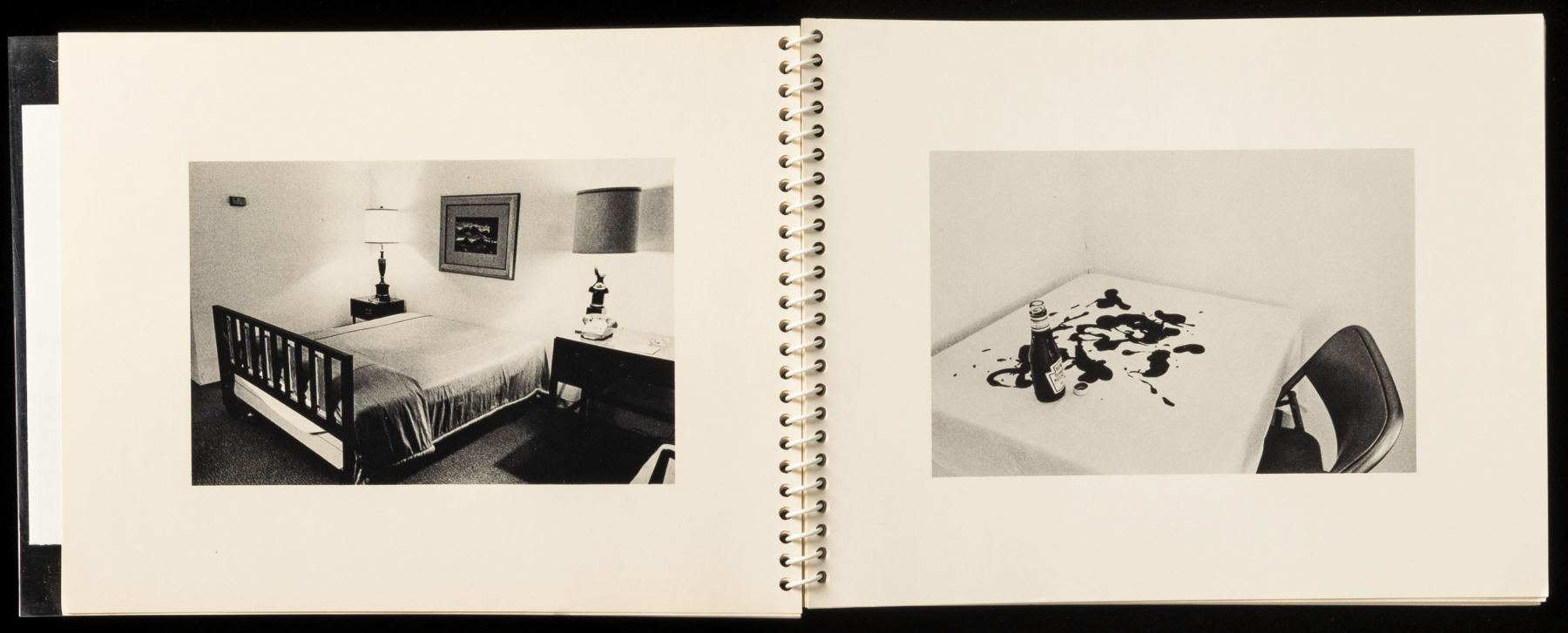

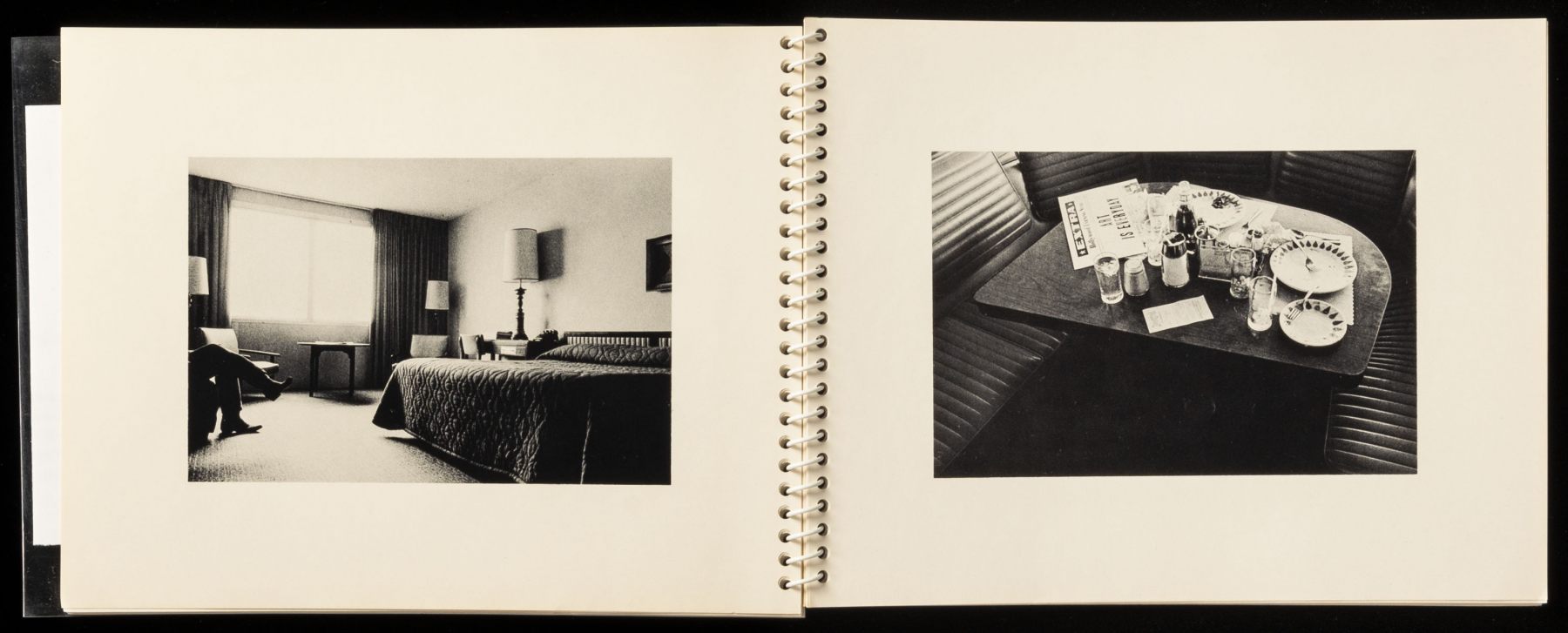

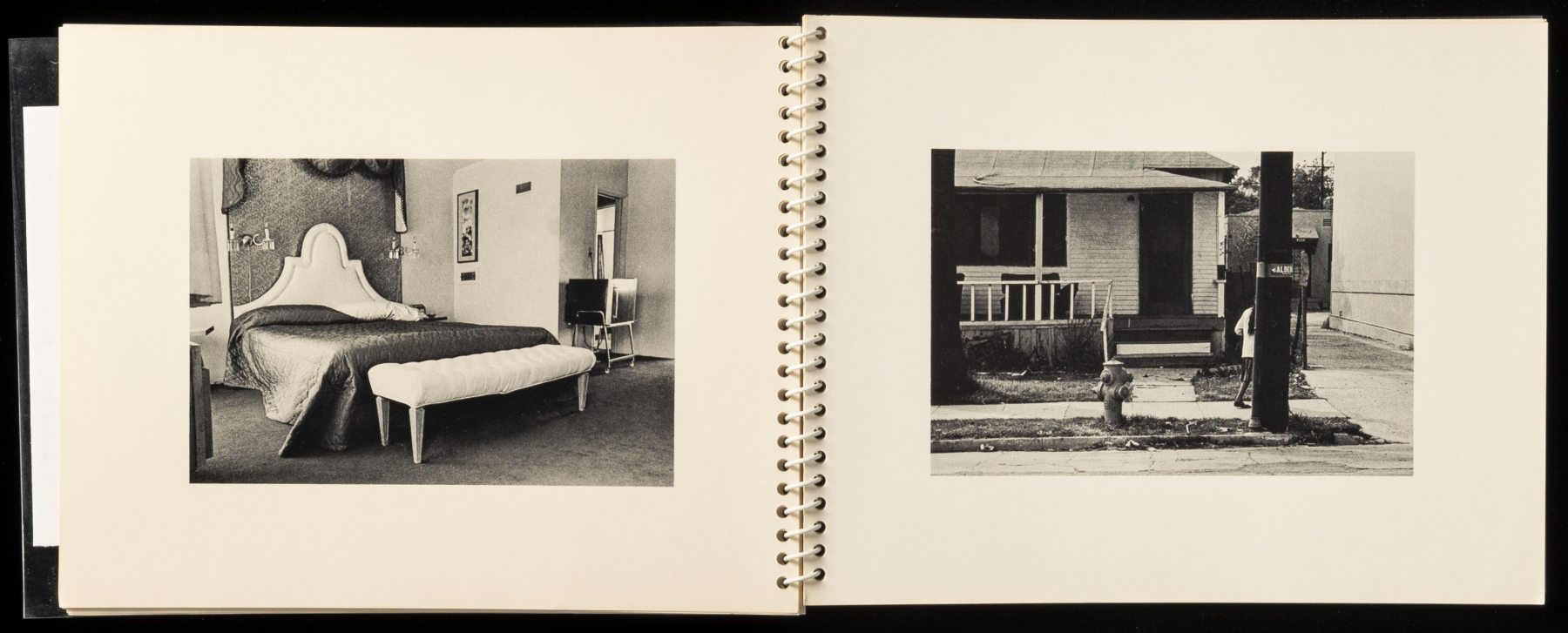

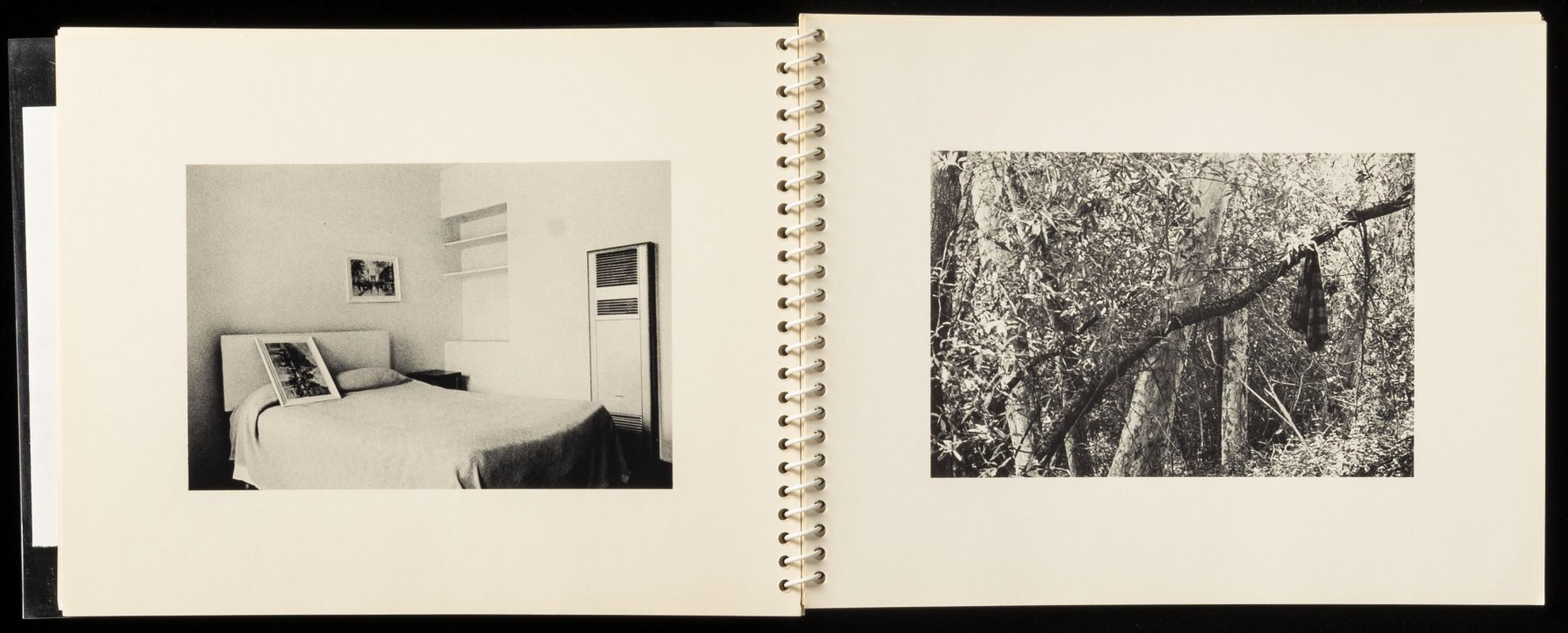

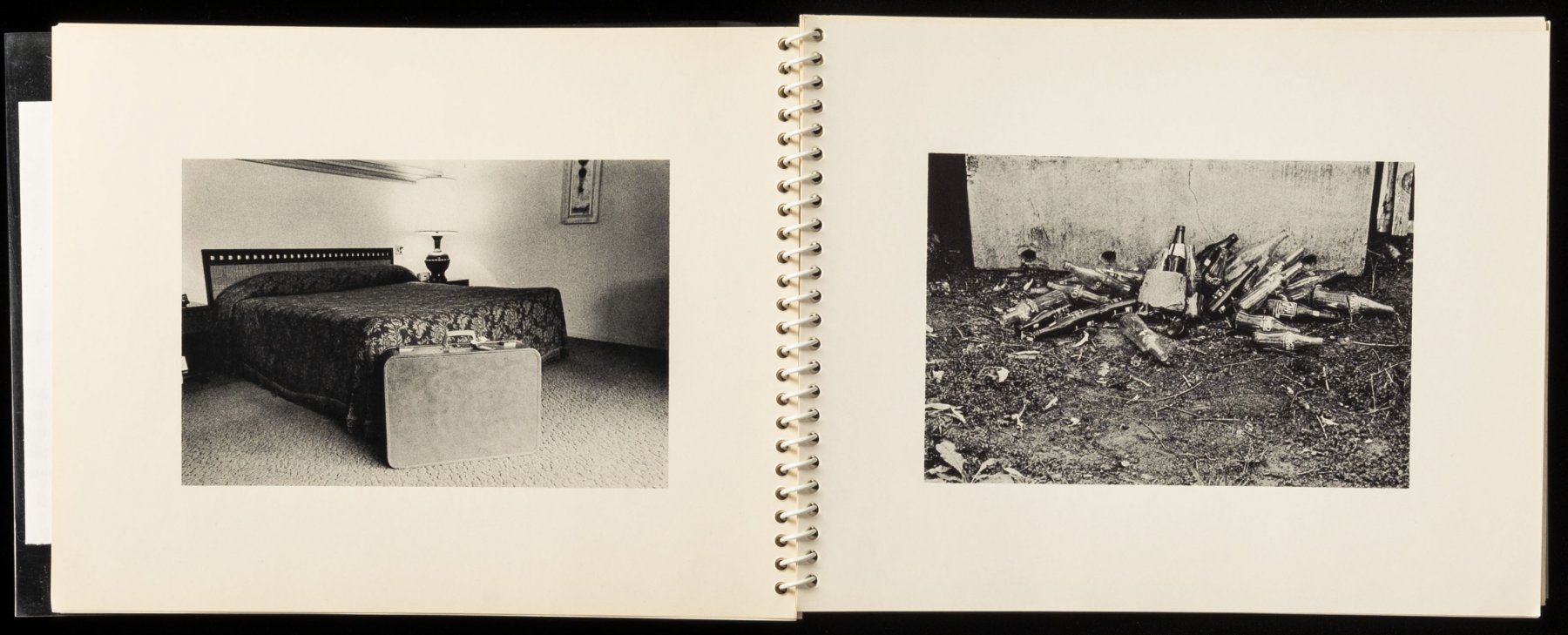

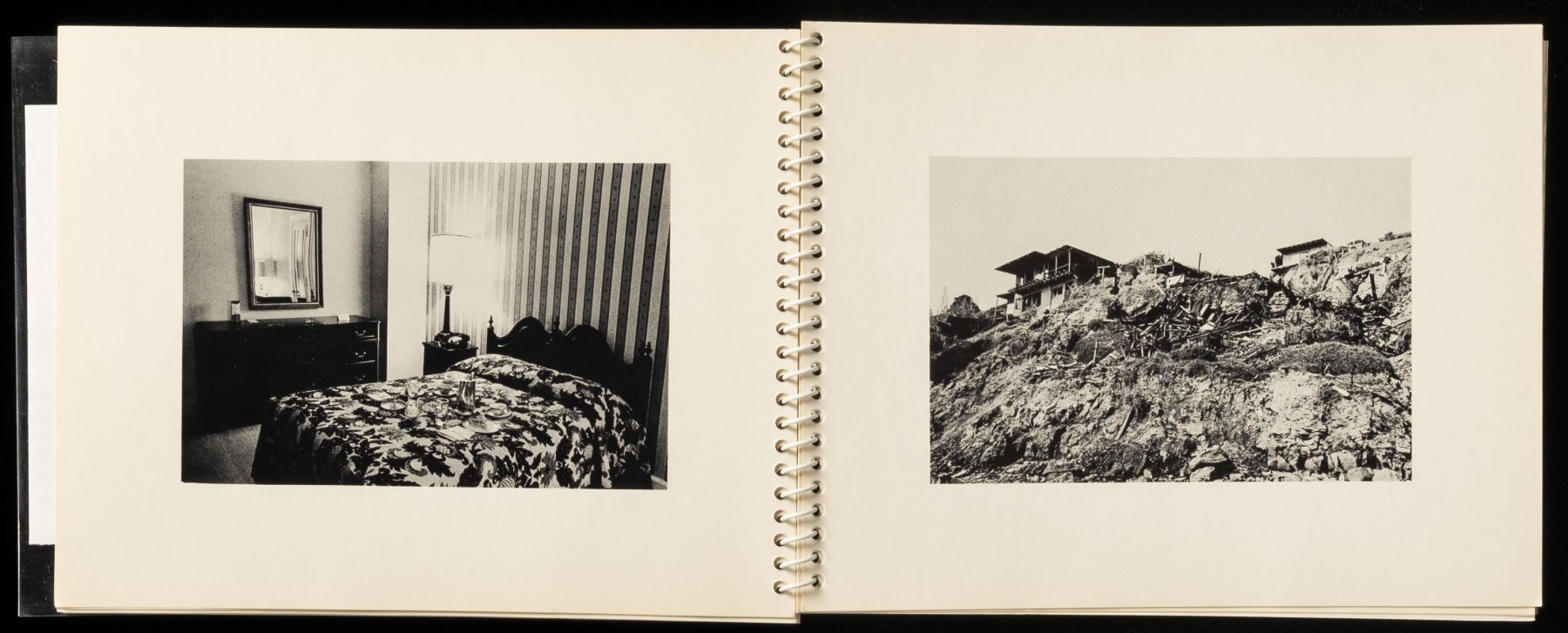

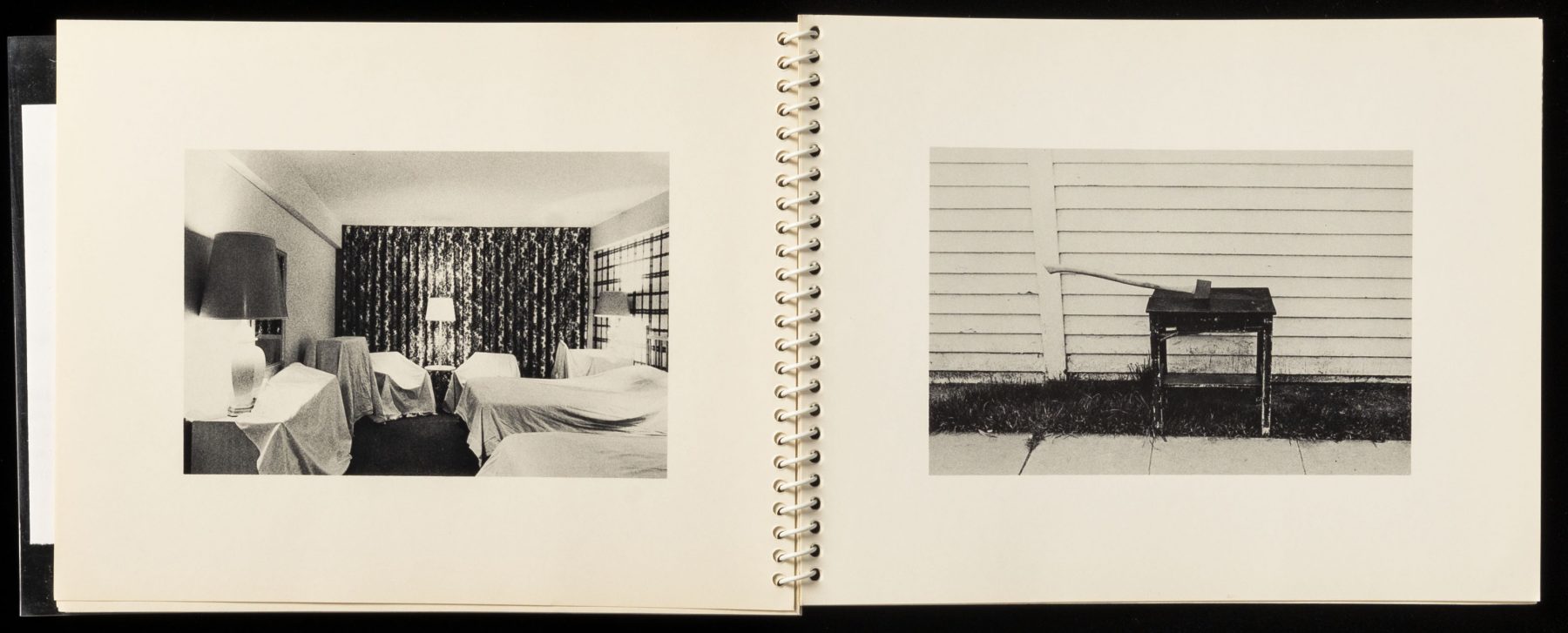

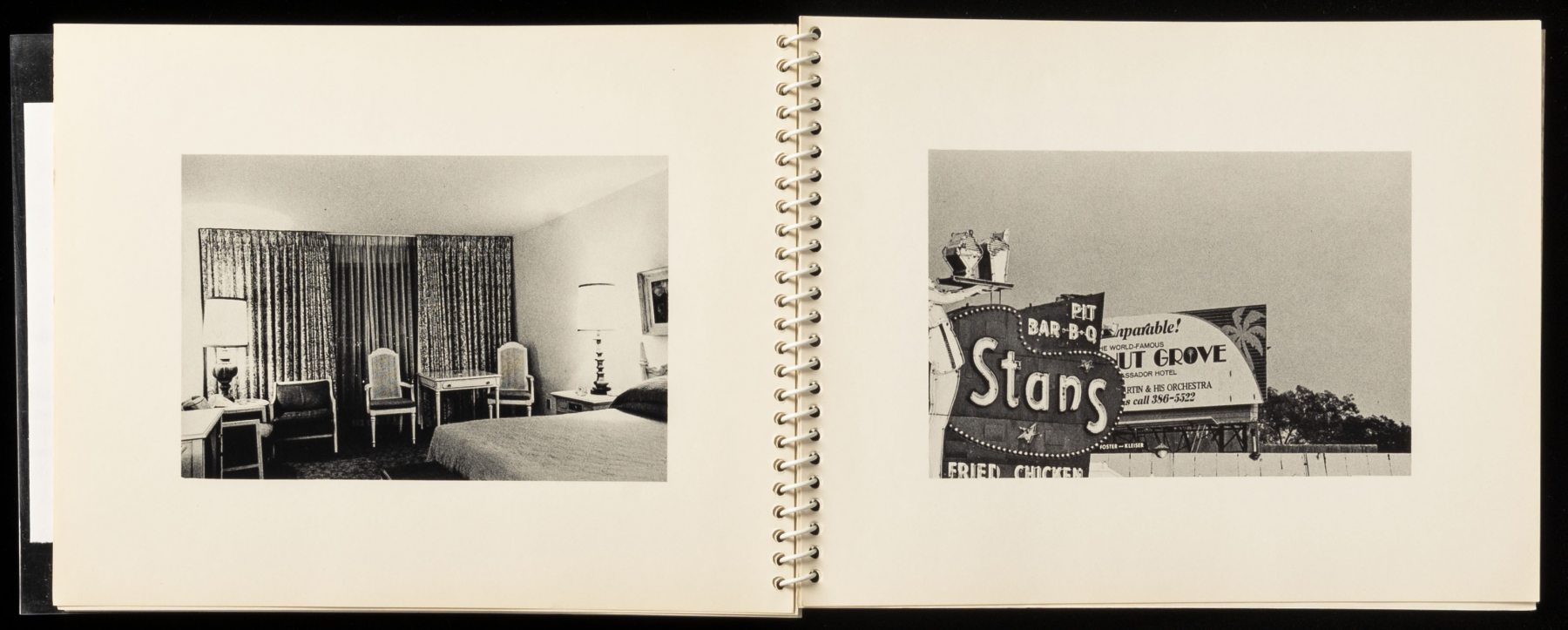

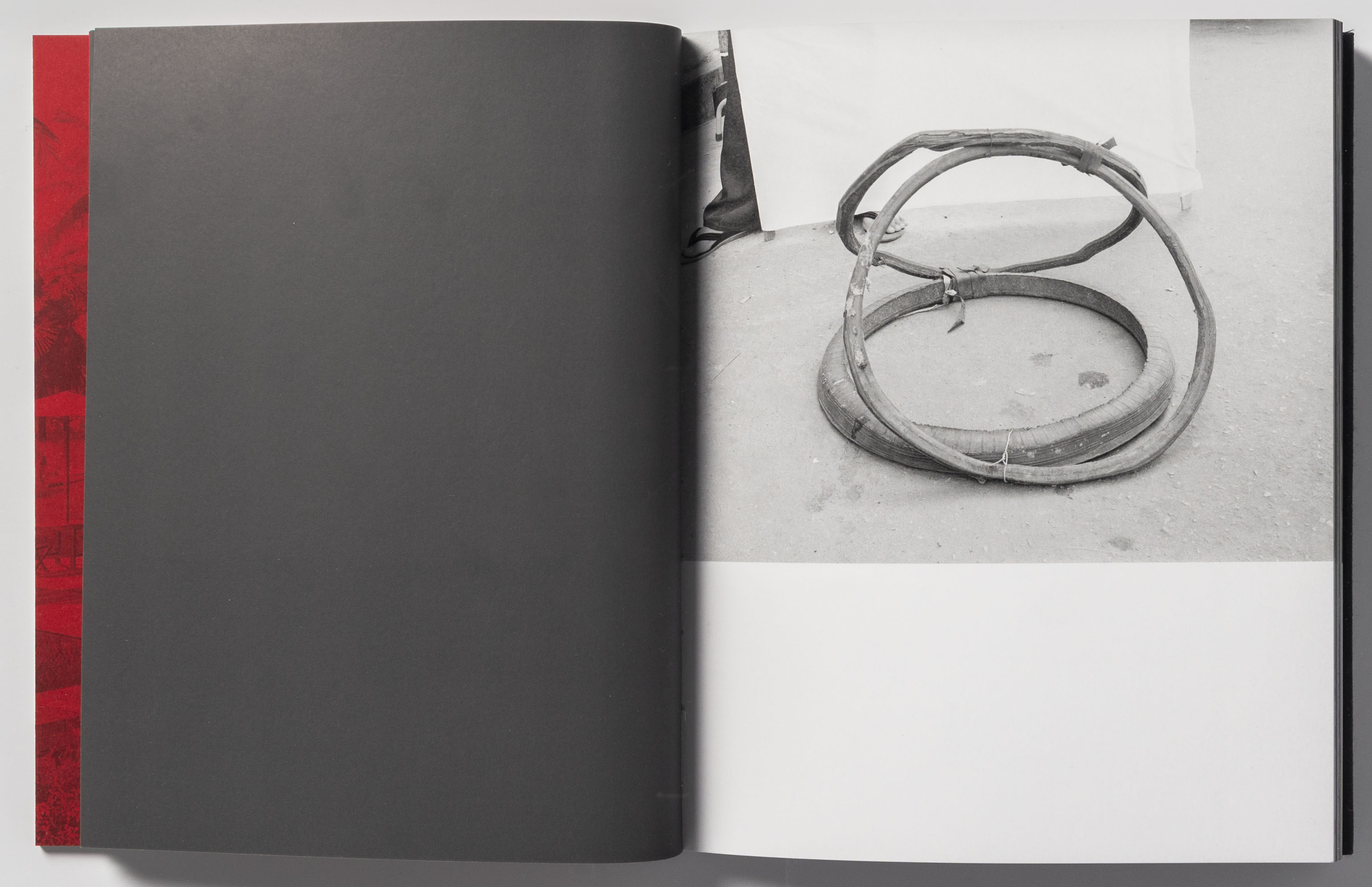

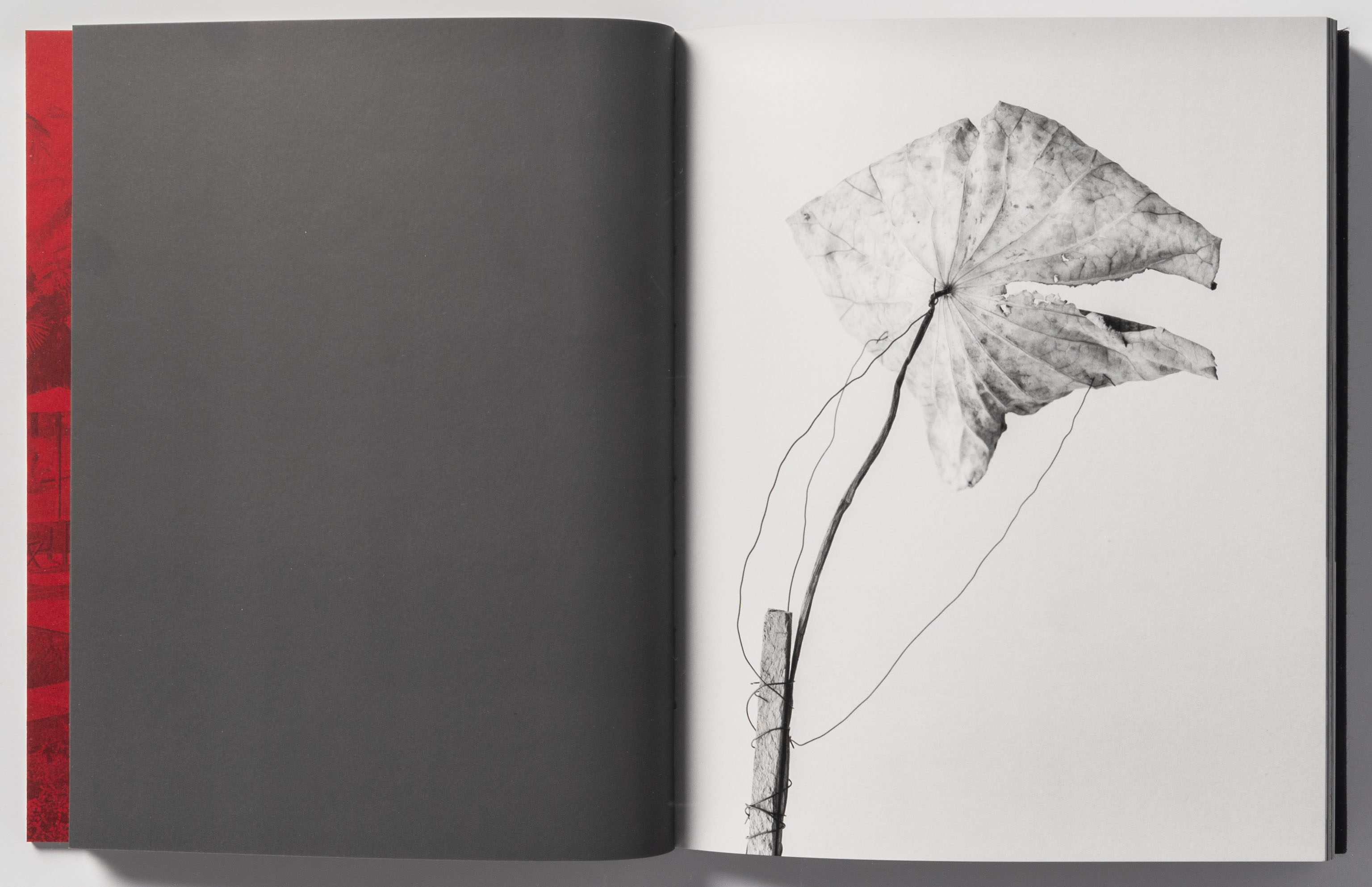

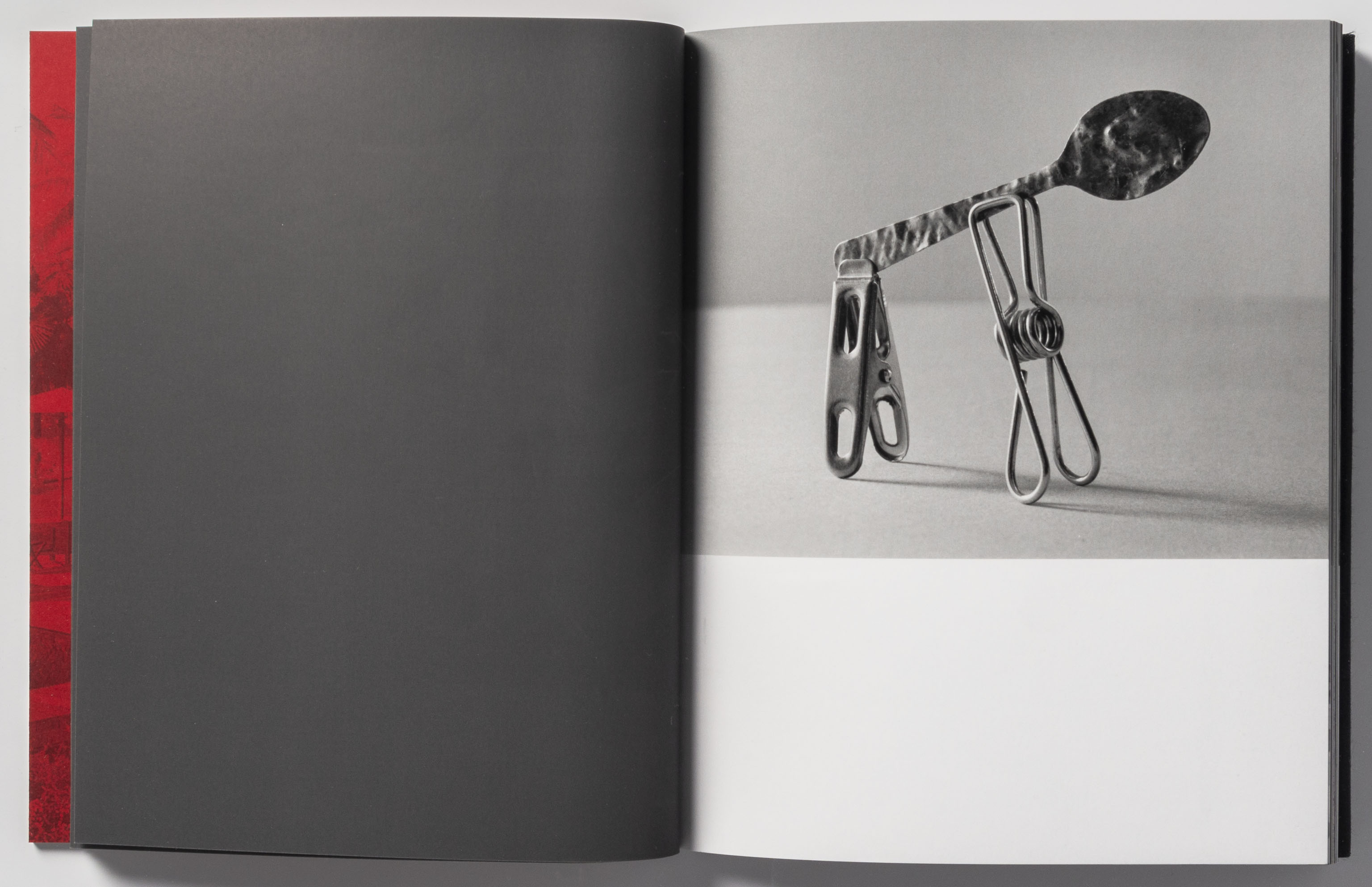

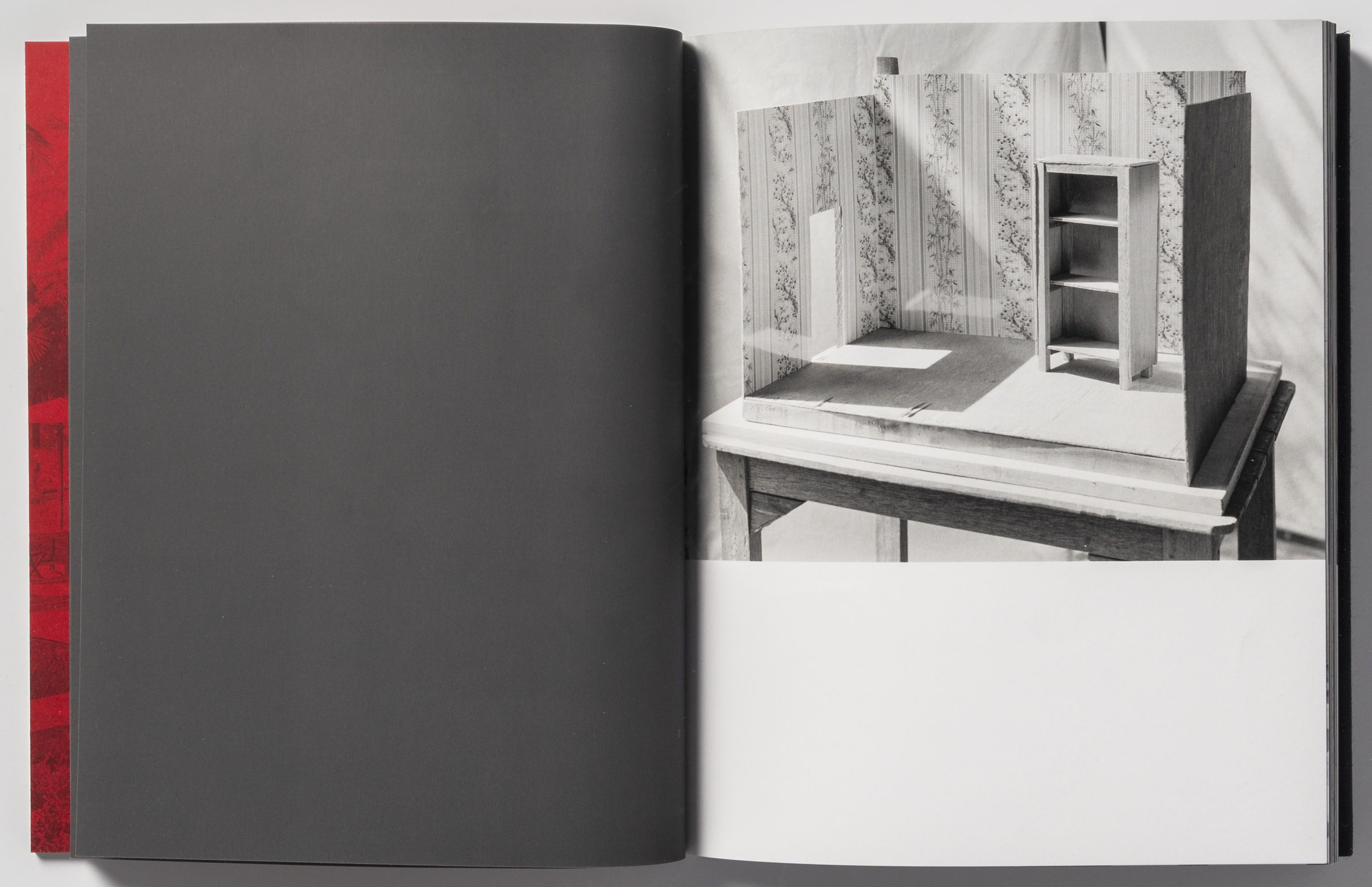

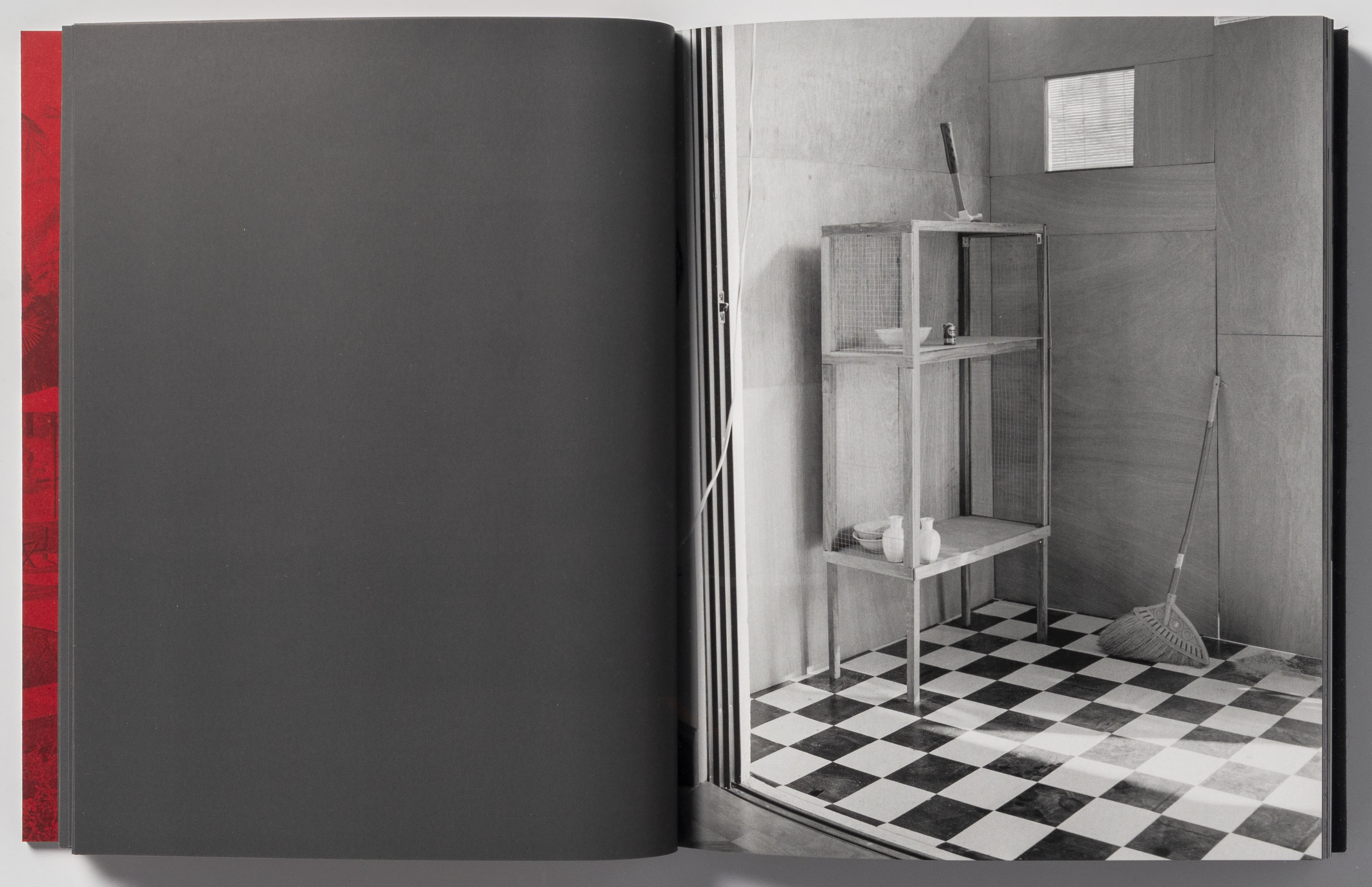

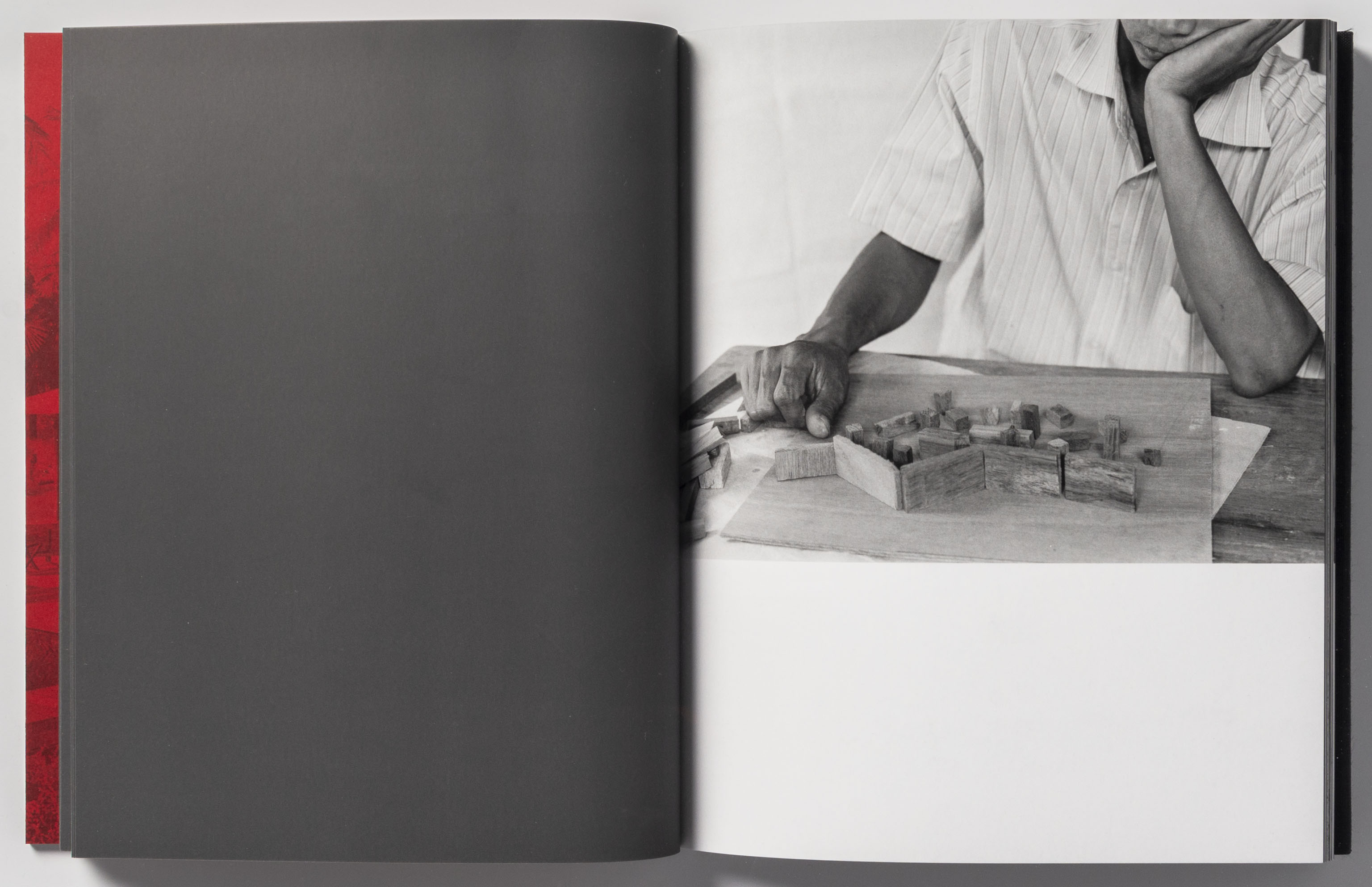

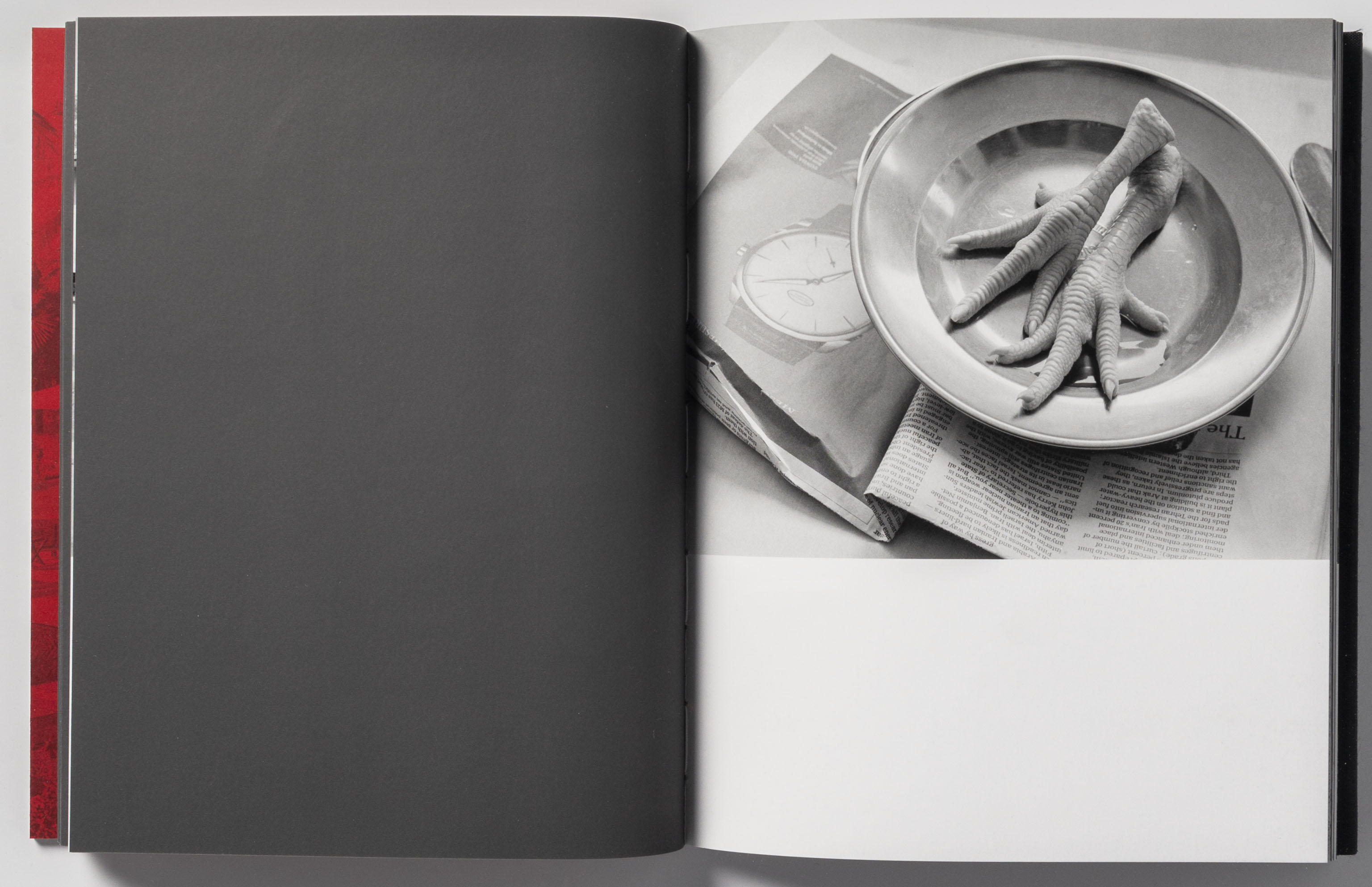

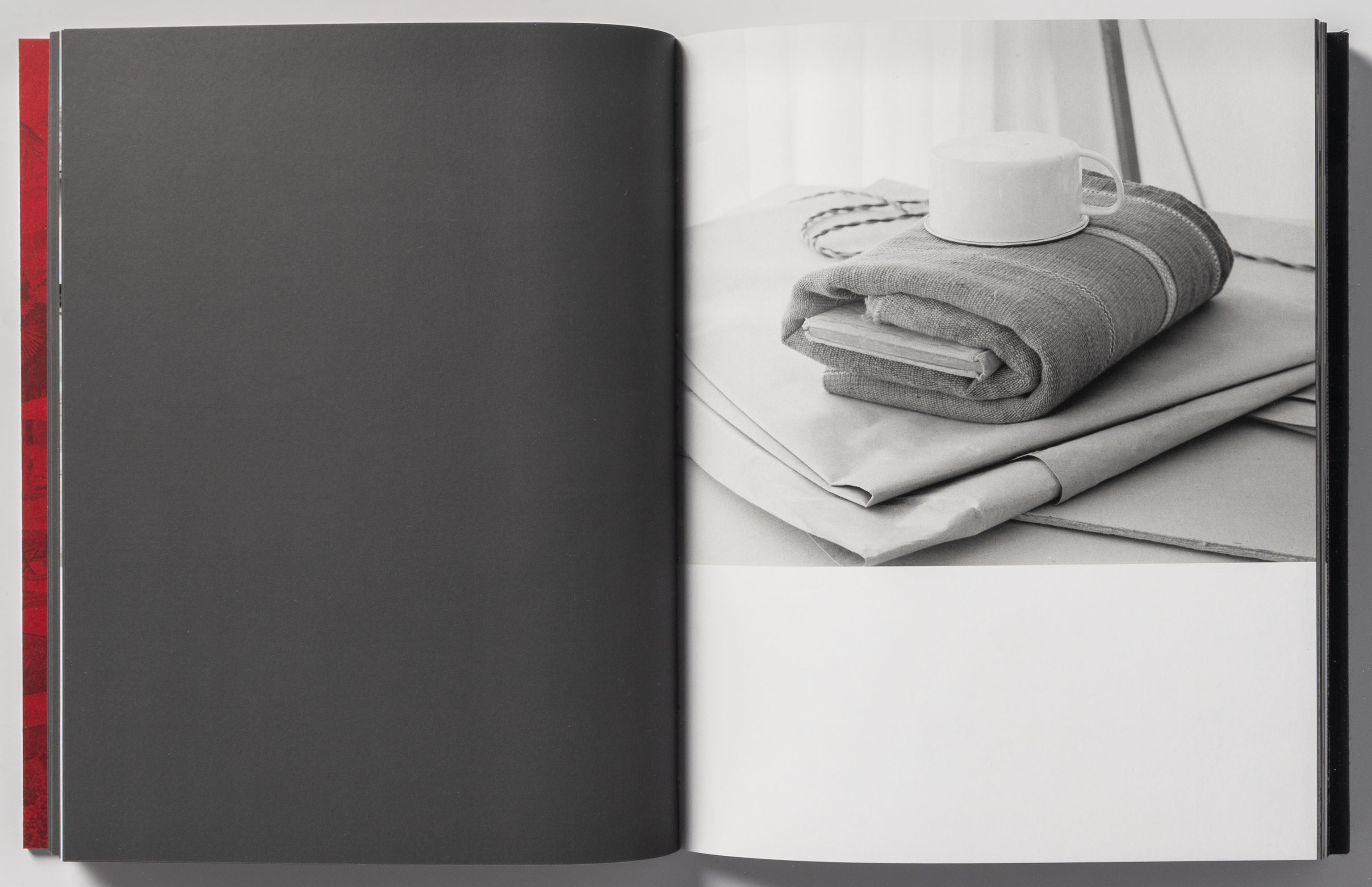

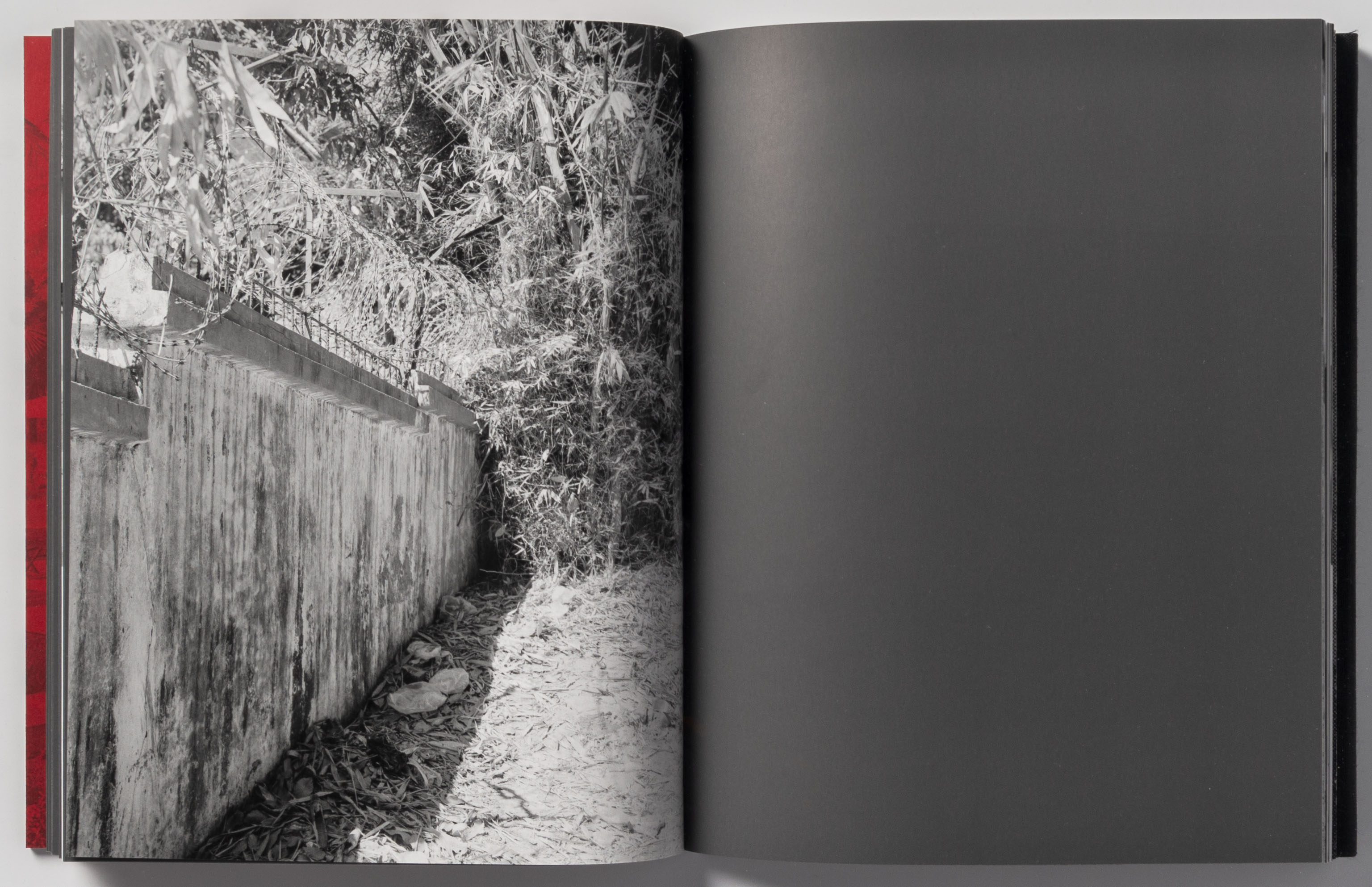

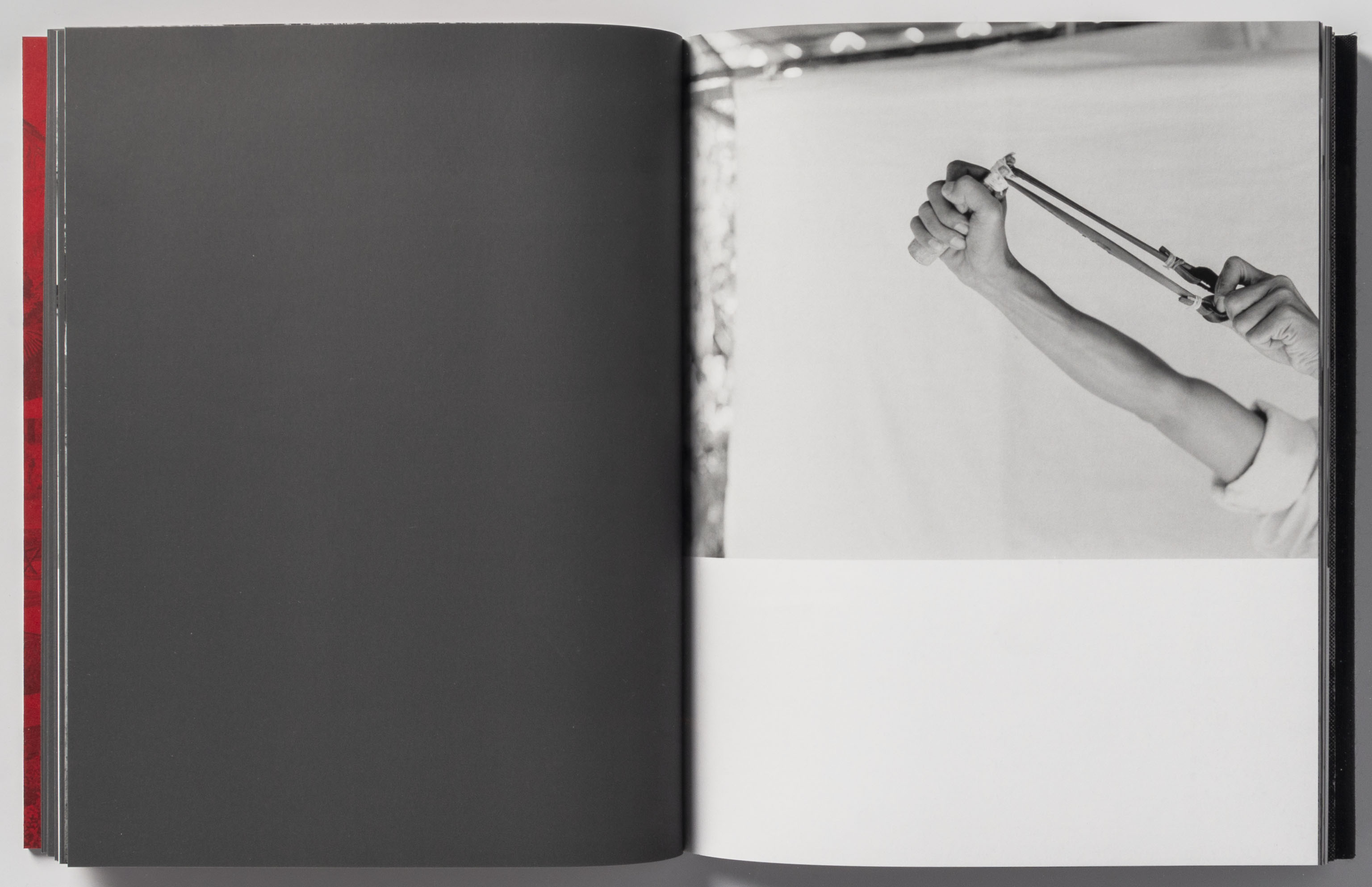

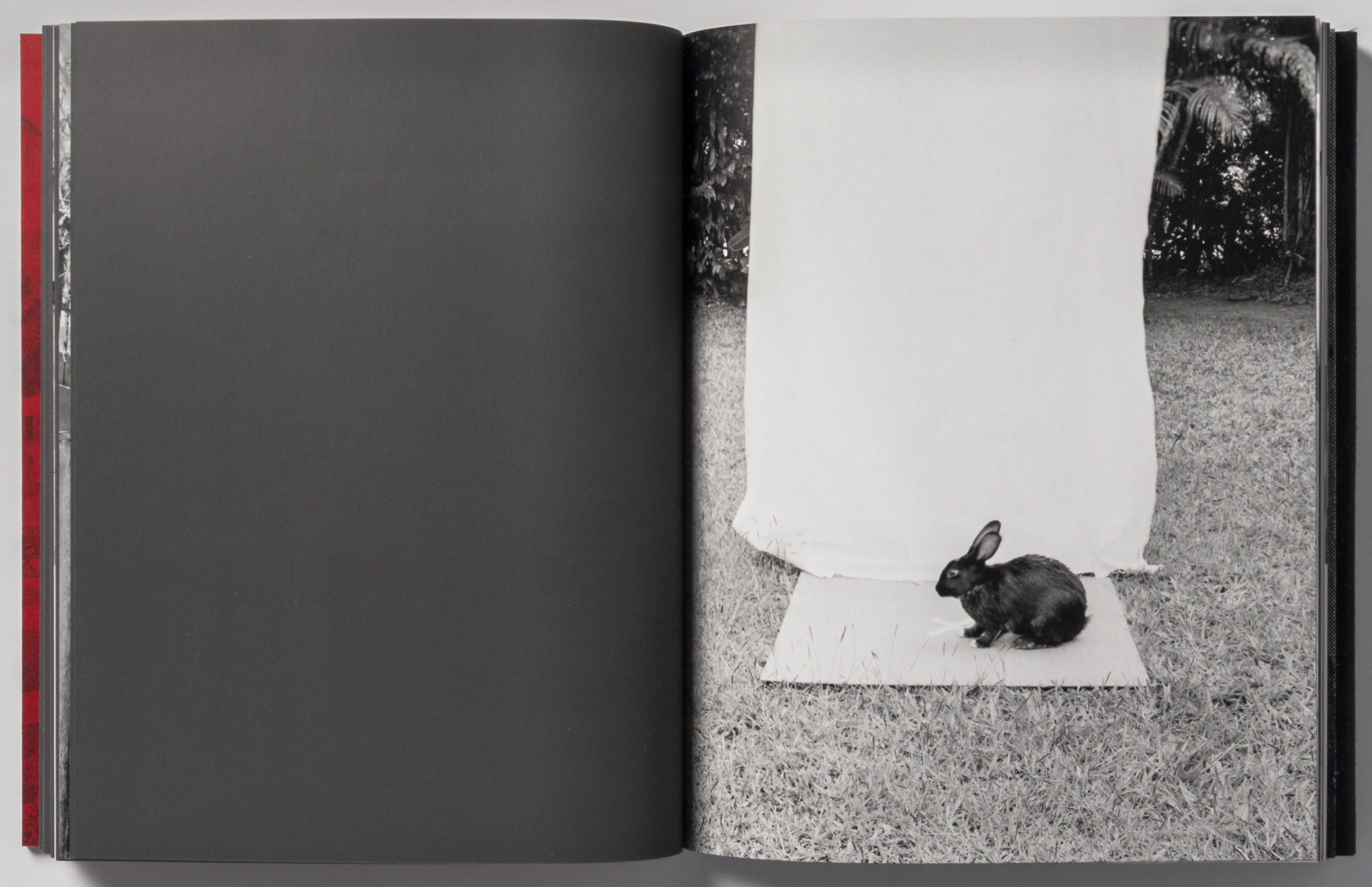

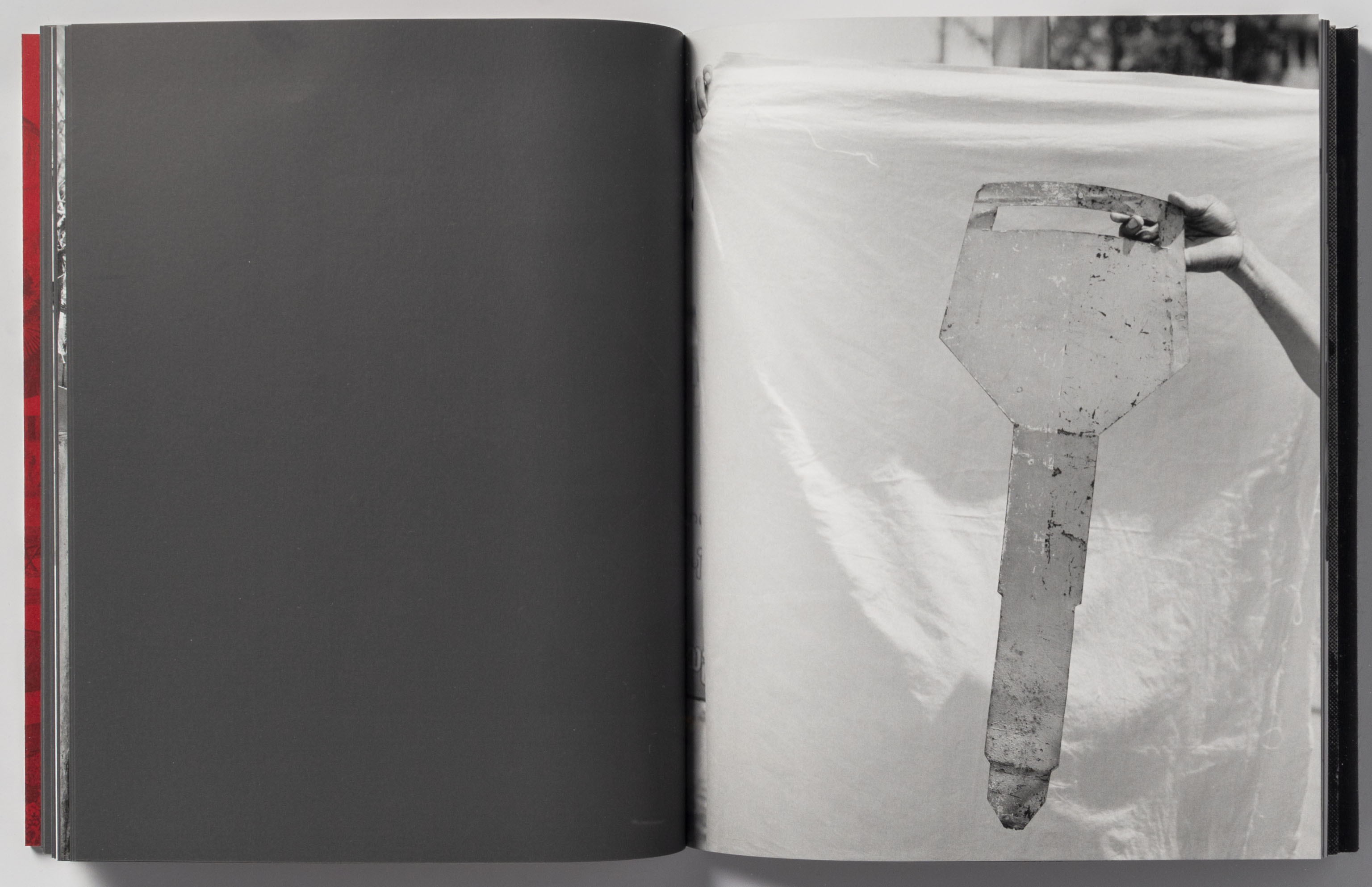

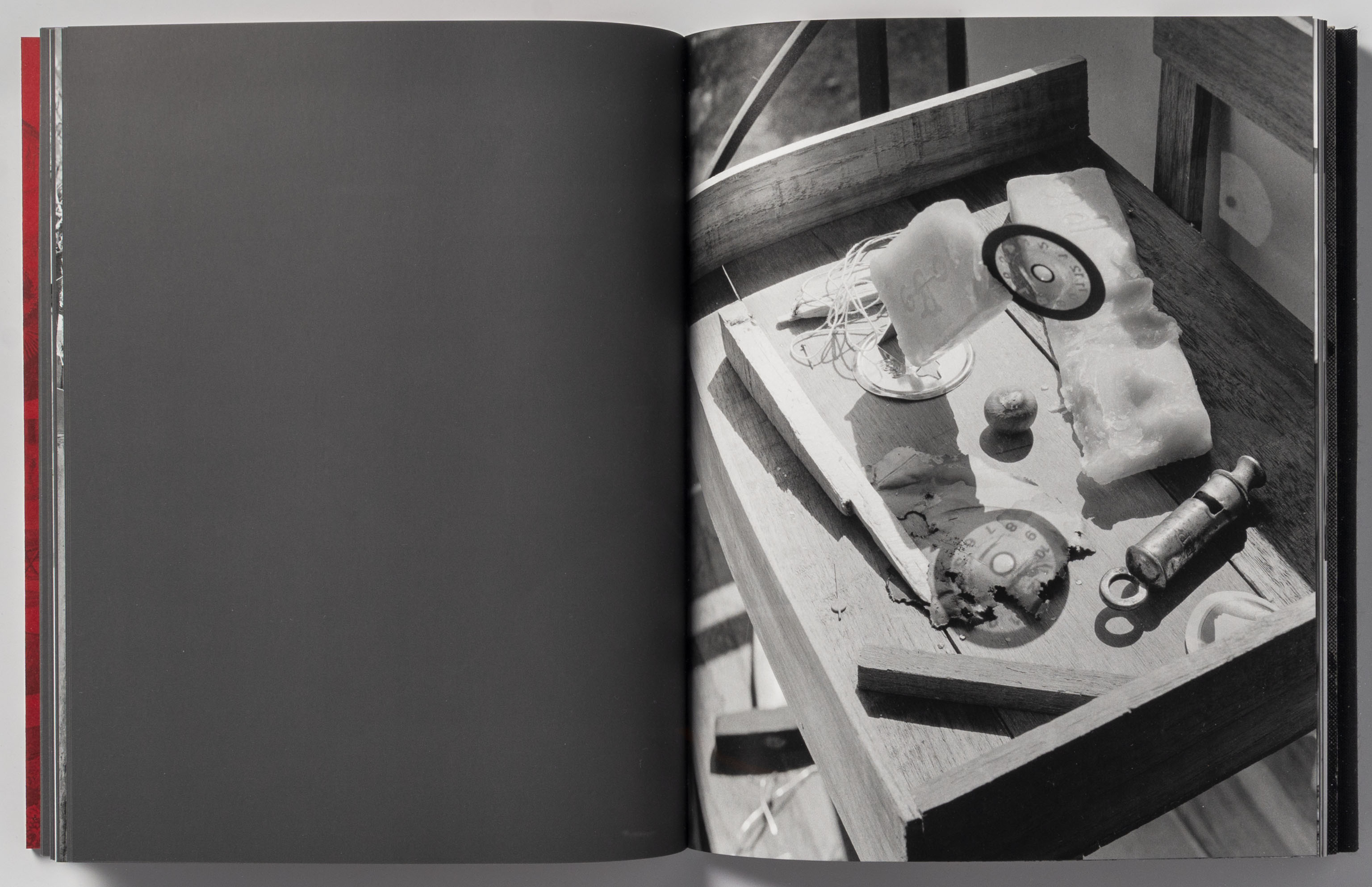

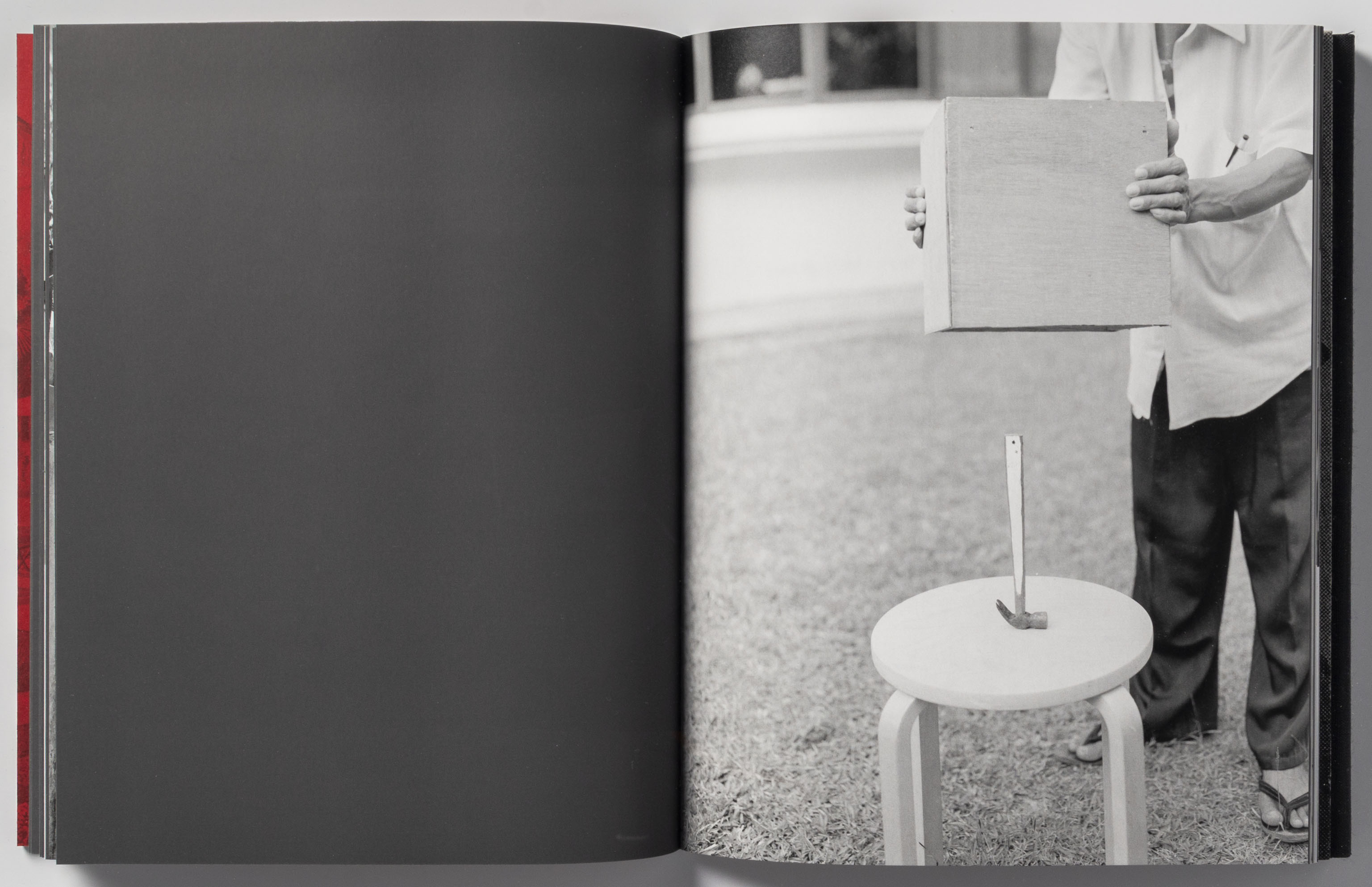

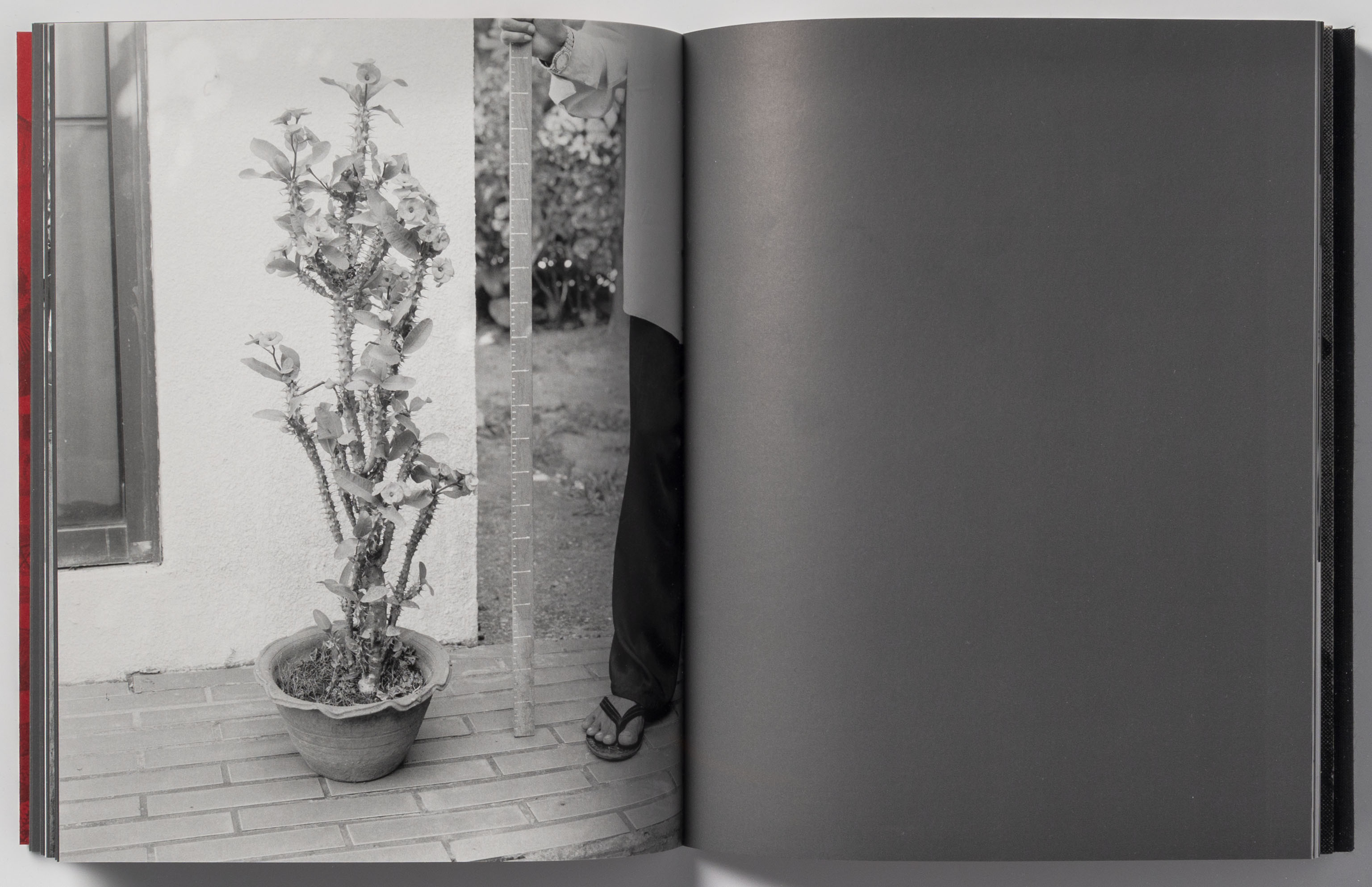

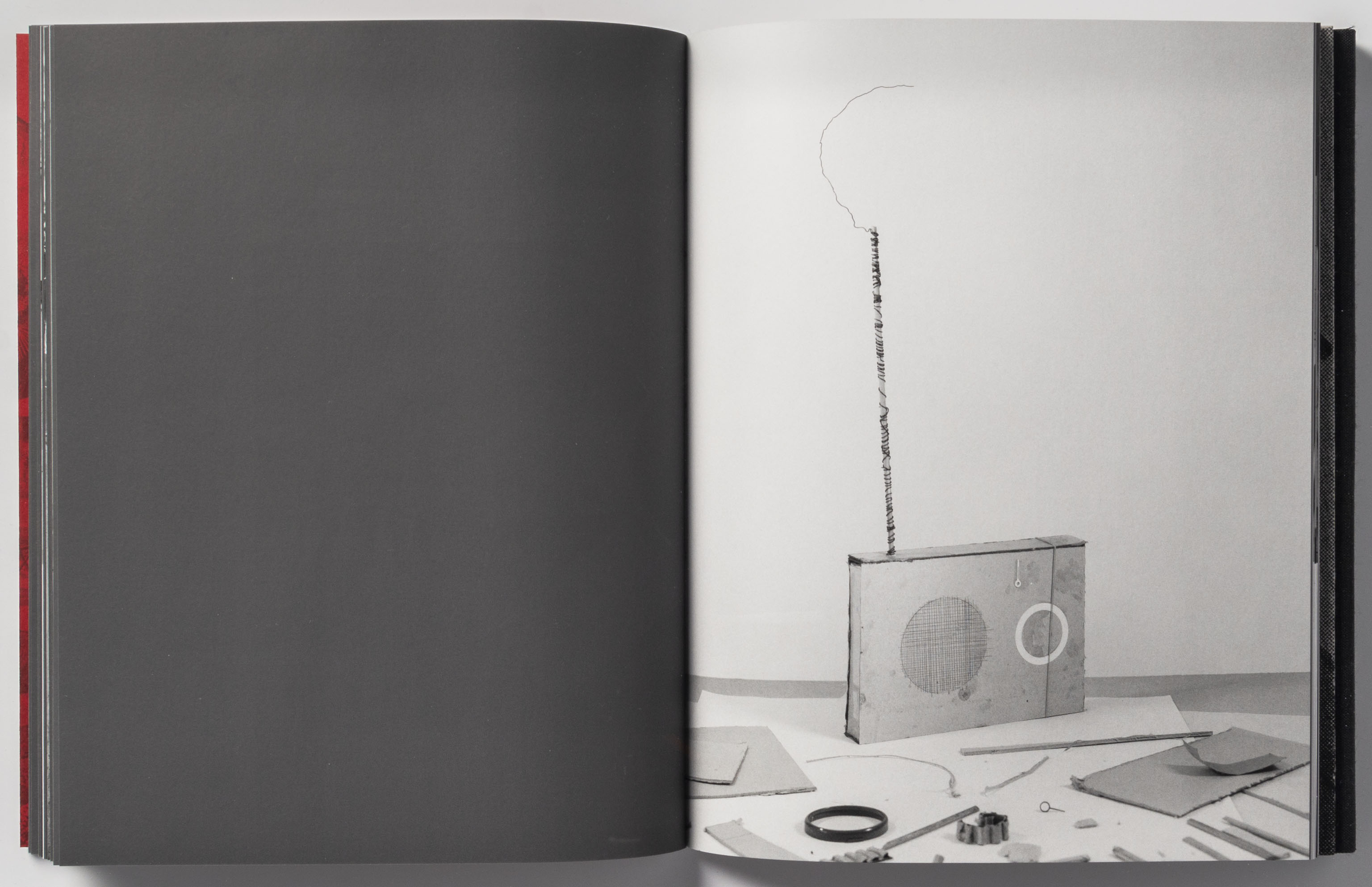

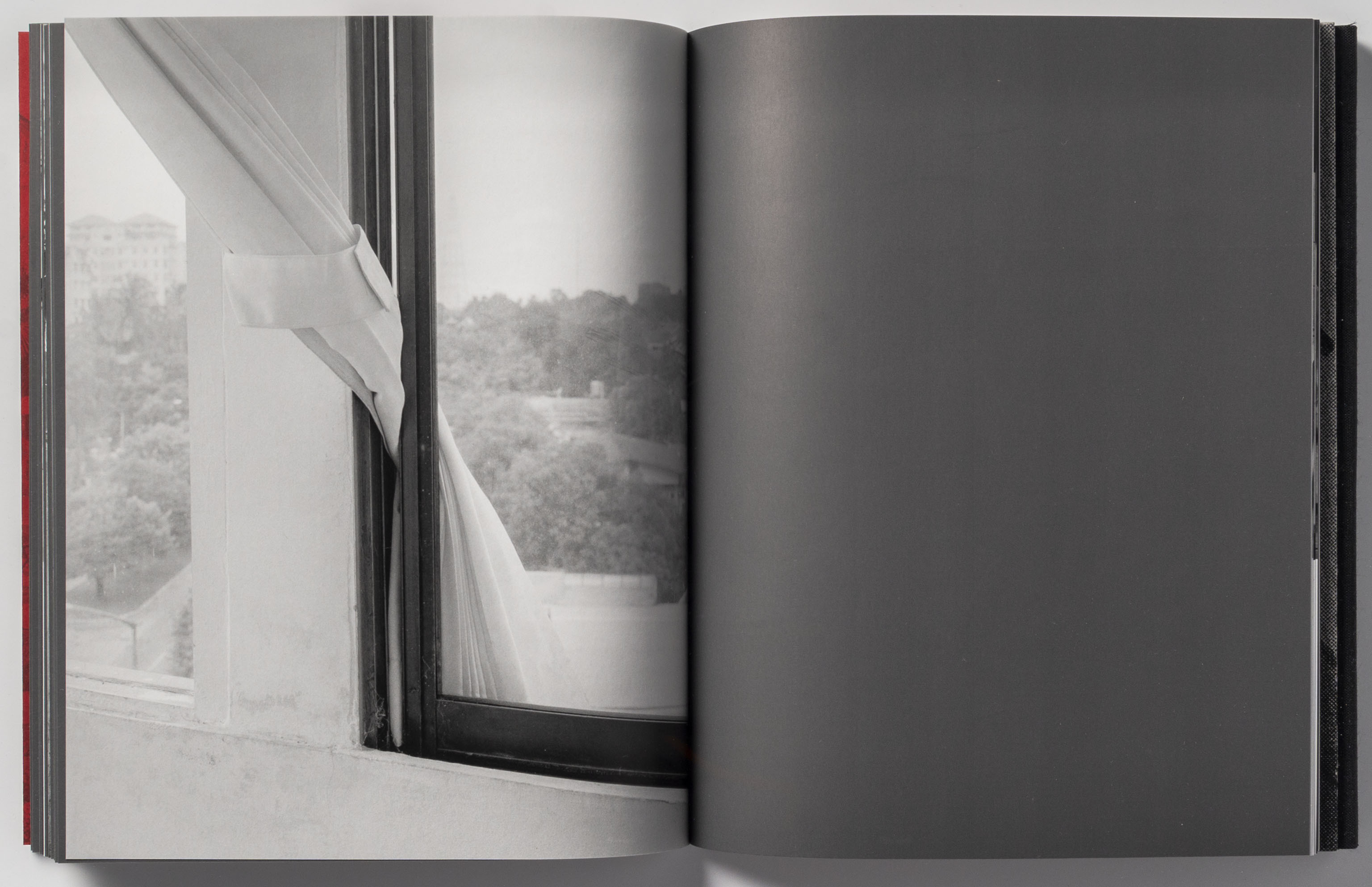

My favorite of the three books is 24 Pieces. Unlike his first book, an Ed Ruscha-ish look at LA, 24 Pieces merges the deadpan aesthetic with qualities of performance and playful narrative suggestion. The twenty-four images are presented in facing pairs. The left-hand image always shows the interior of a hotel room while the right-hand page varies. Looking closely, one can always find an act of human intervention within each pair. Each spread functions like an equation: A (hotel) + B (random image) + C (intervention) = suggested narrative.

In his forward to 2000 reprint of the book , Christophe Cherix writes:

“In the end it is up to the spectator to make the connections and the oppositions, to construct his own stories…Ruppersberg recently told the story of a person from the American South (where the weather is often violently unpredictable) who interpreted the third and fourth pictures in the following way: during tornadoes (a newspaper pinned on the wall shows a tornado), which usually occur around 3 in the afternoon (the time displayed on the clock on the shelf), one must hide under the mattress (the left picture shows a bed whose mattress has been displaced.) It is not necessary to point out here that the artist was totally unware of these facts at the time of the publication.”

24 Pieces is one of my all-time favorite photographic books because it strips down the mechanics of photographic narrative into simple parts, but never gives into an obvious formula. This modest book of 24-pictures by a 24-year old artist continues to be a springboard for my imagination.

See 24 Pieces in its entirety HERE.

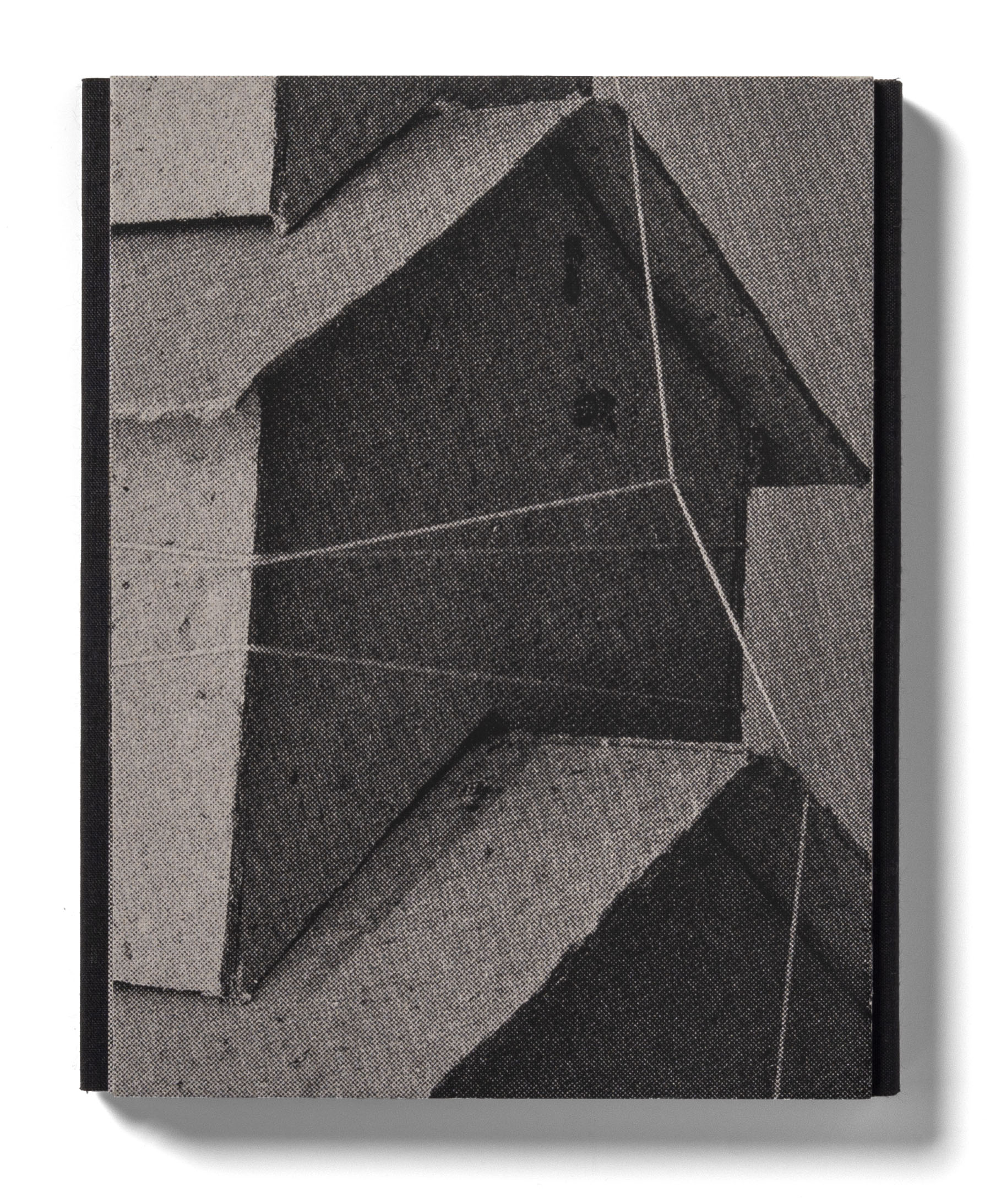

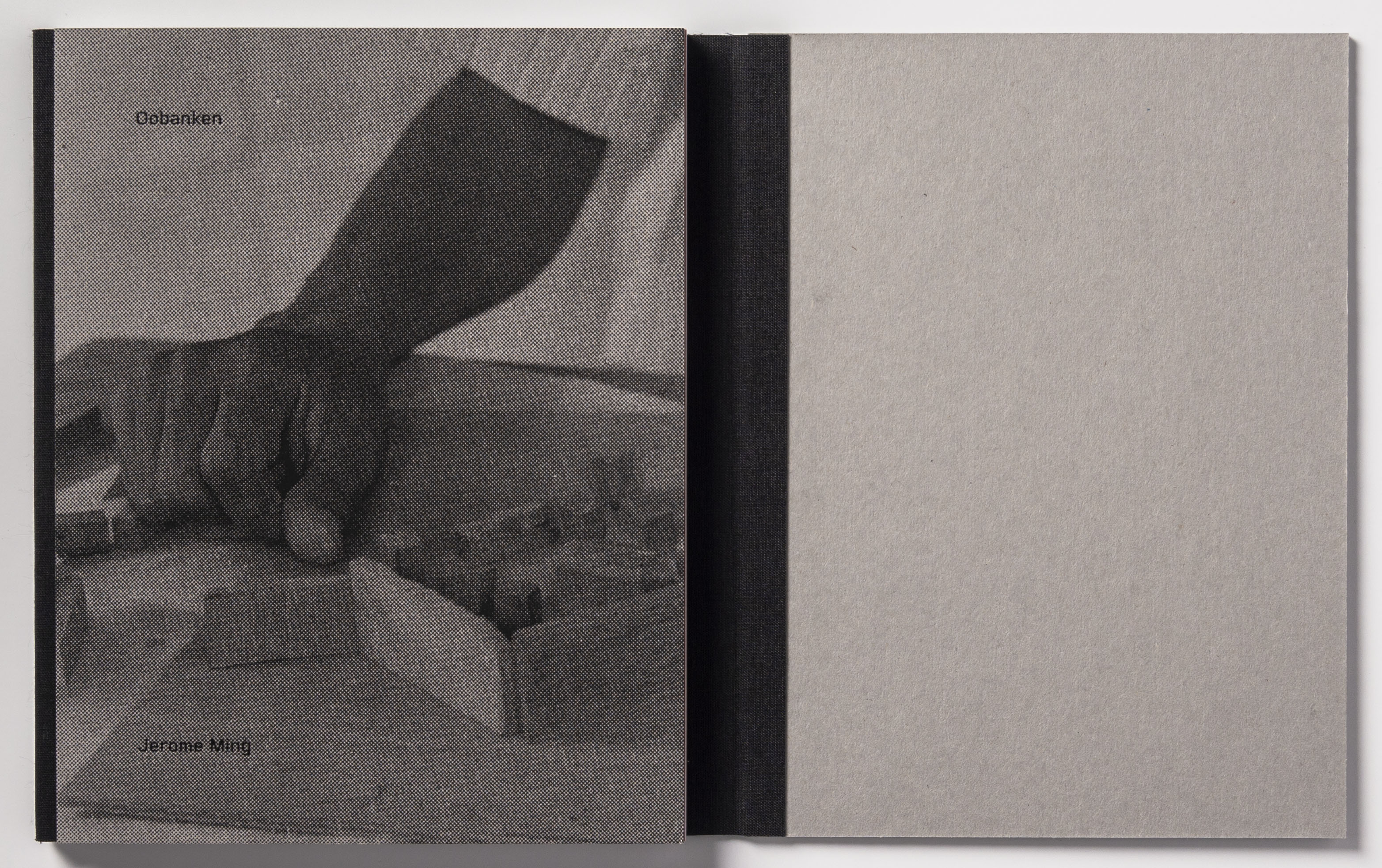

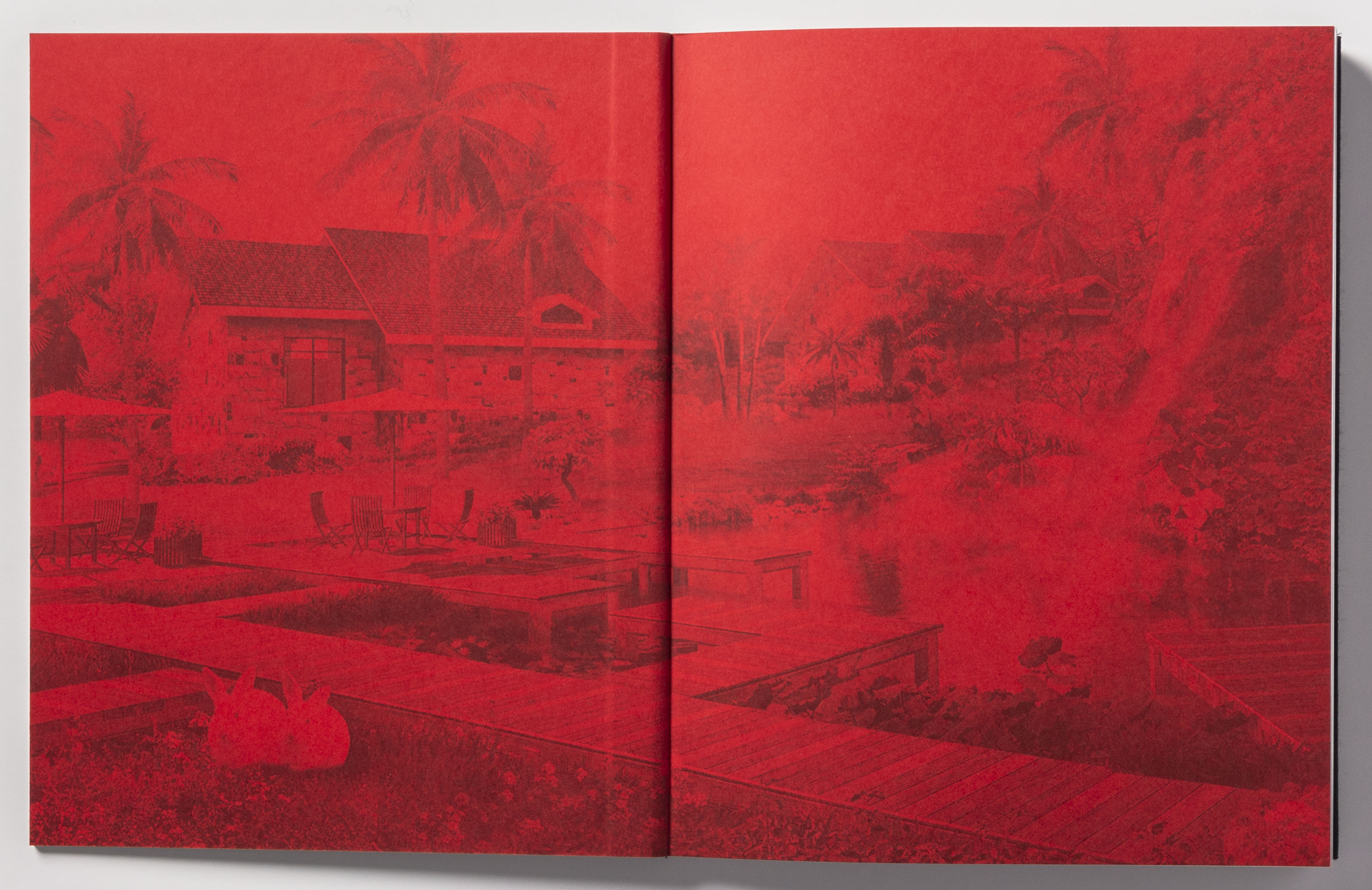

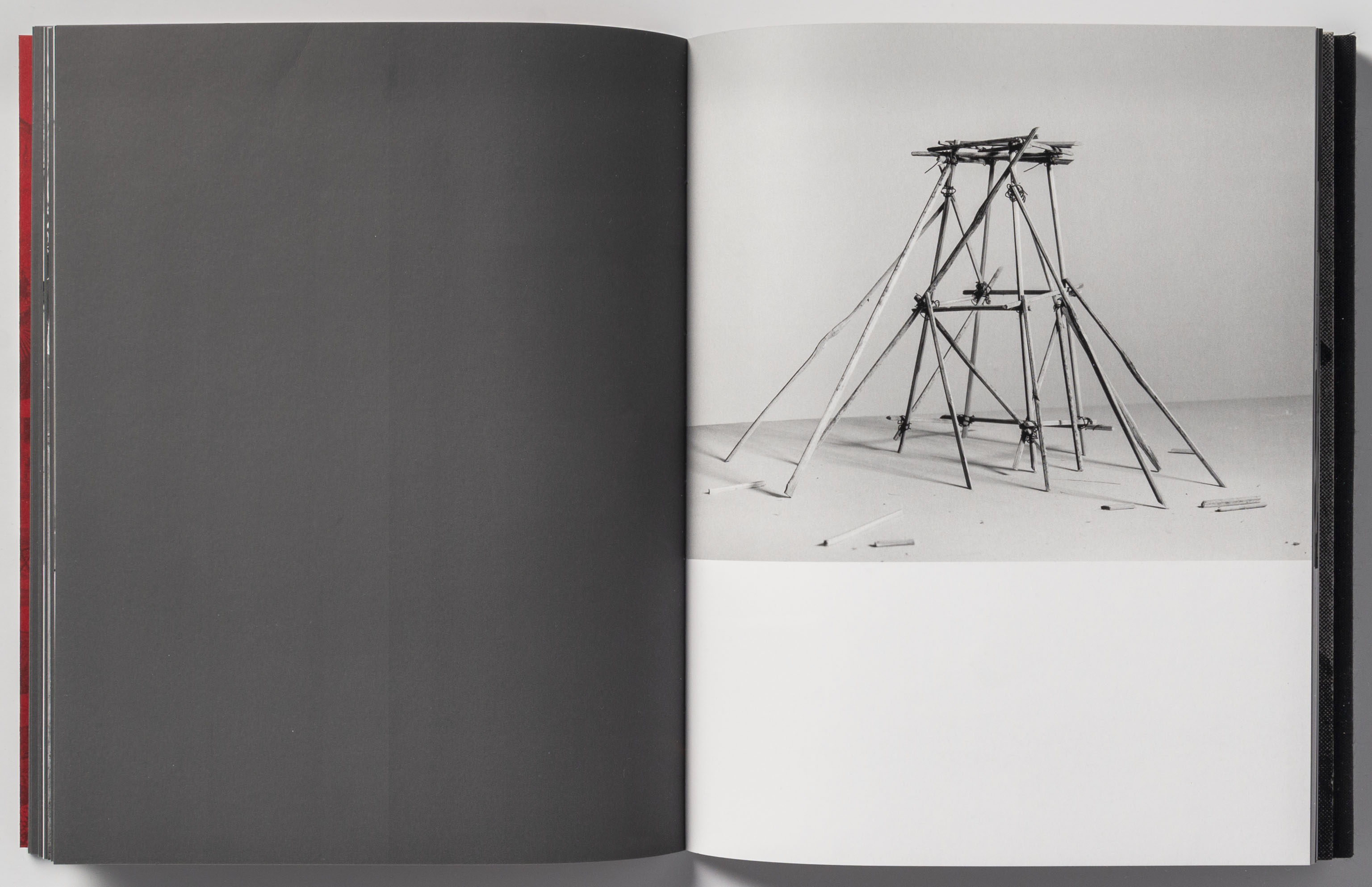

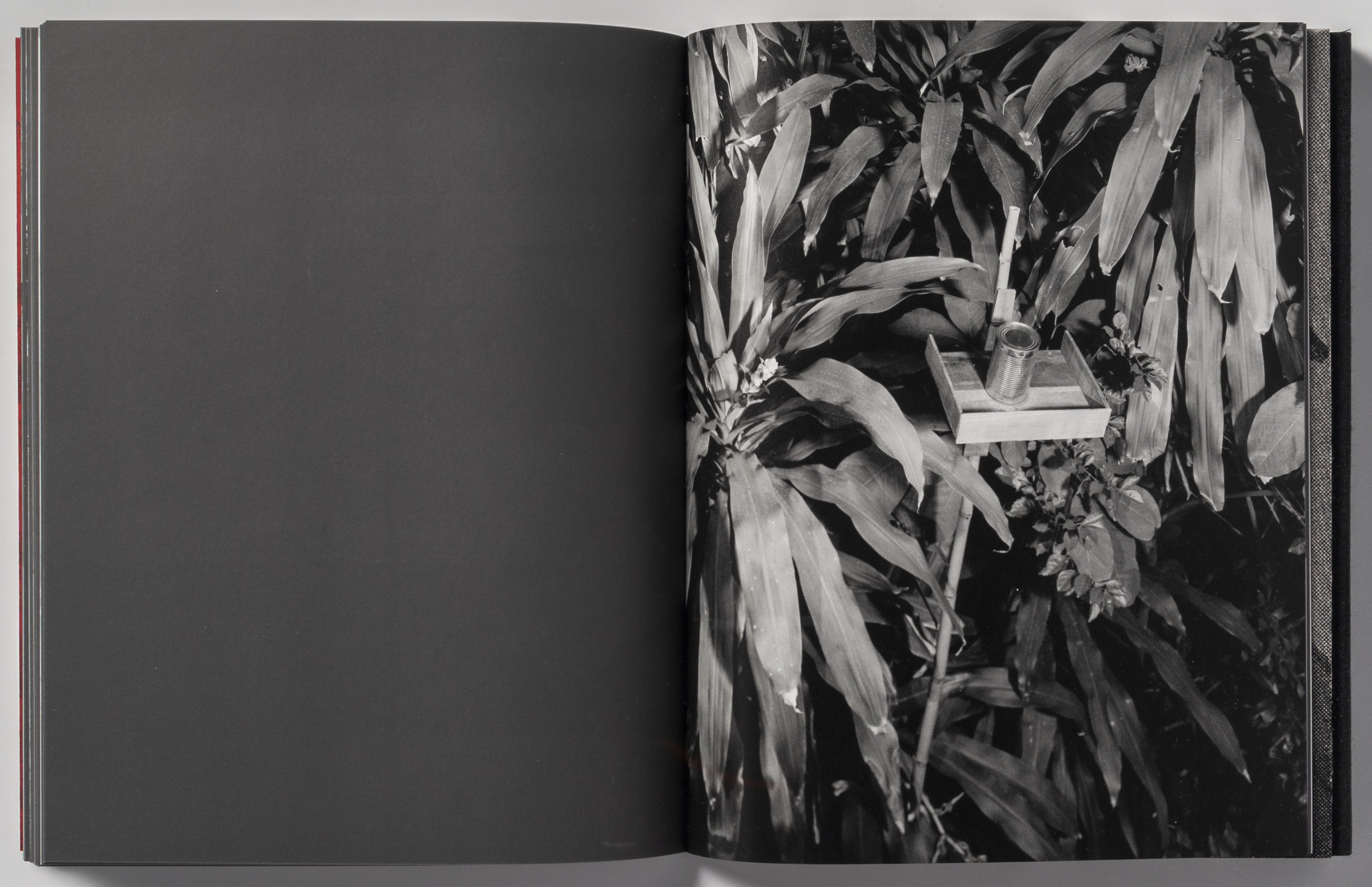

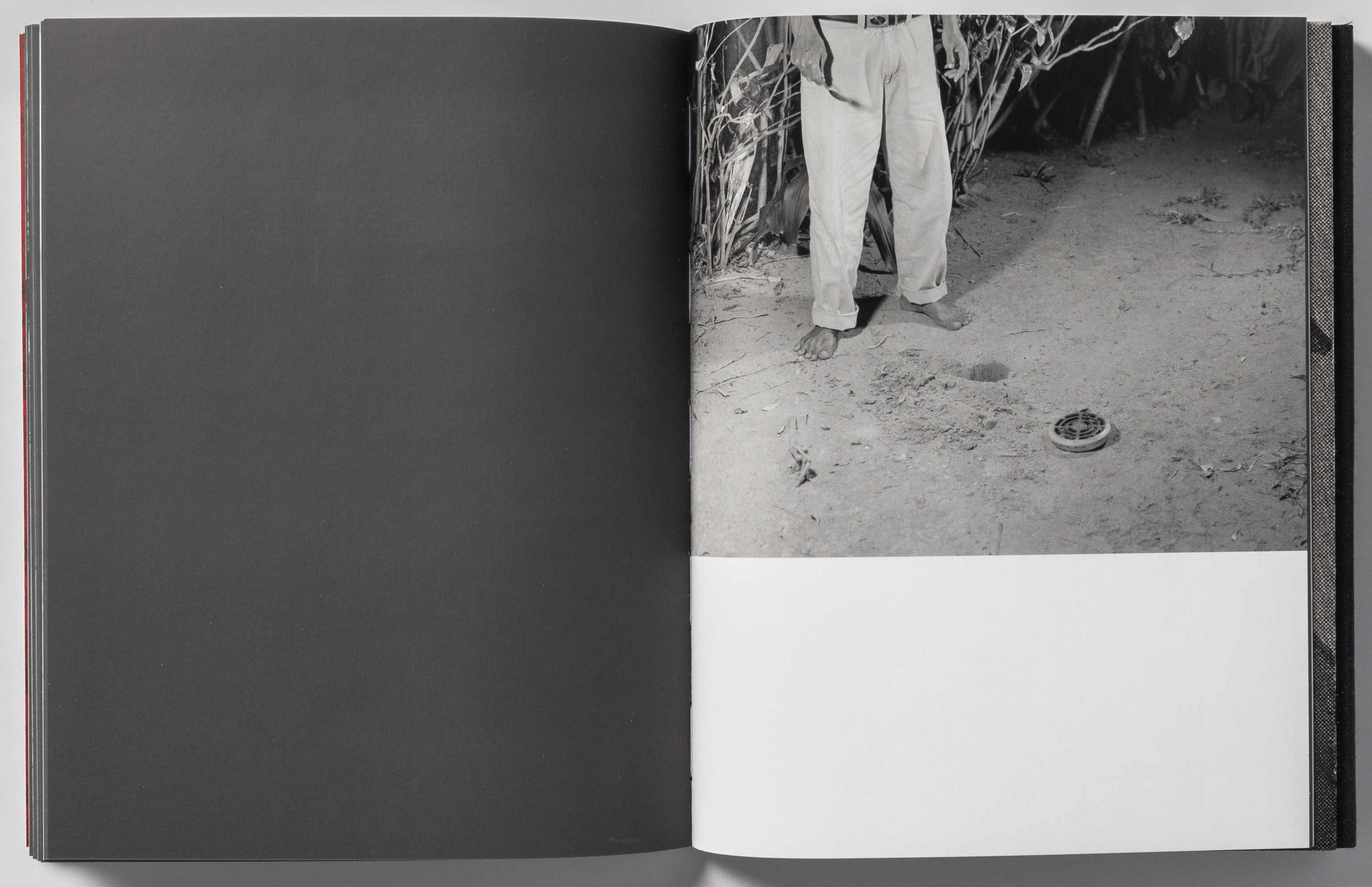

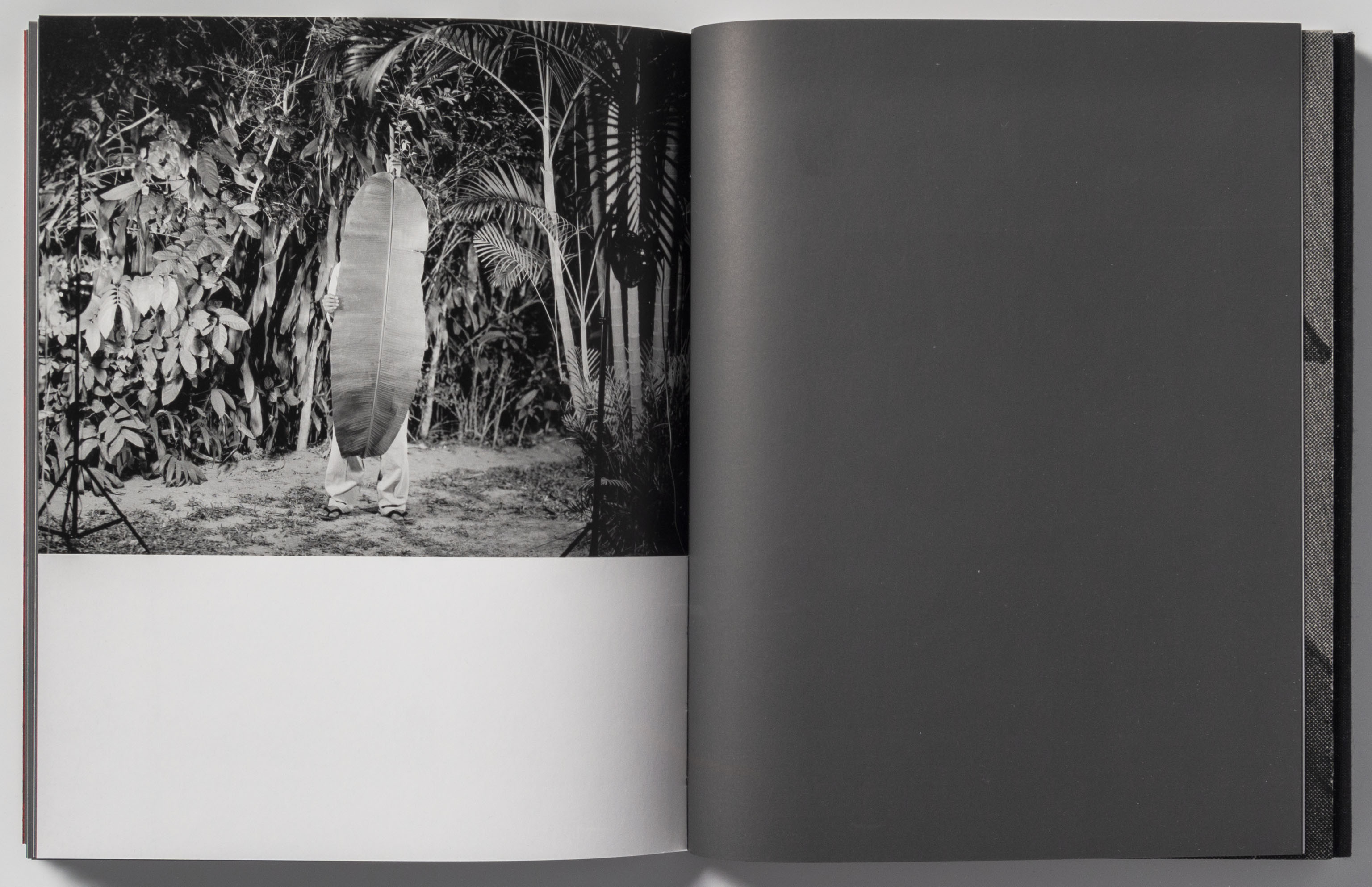

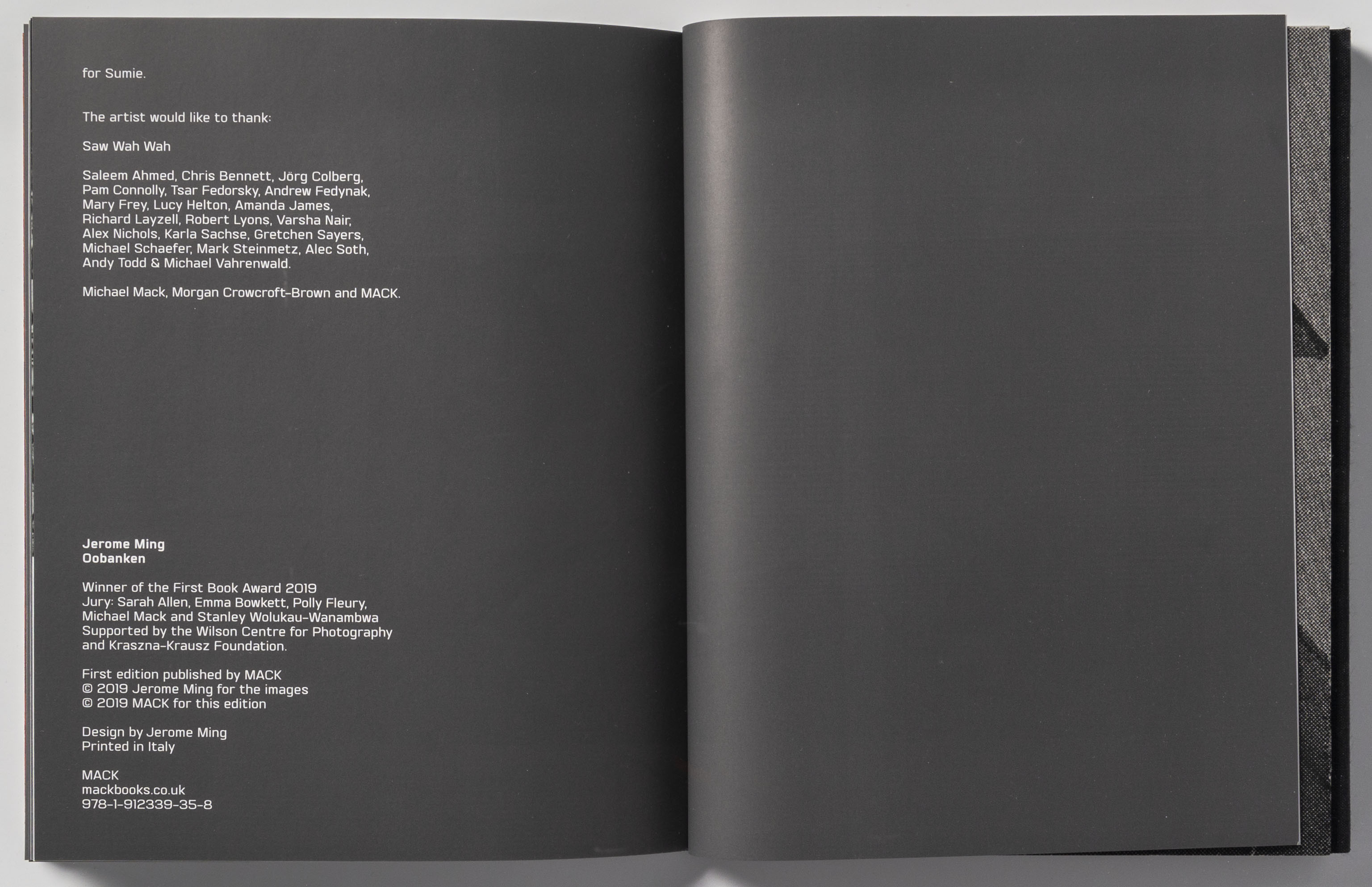

Recently Received: Oobanken by Jerome Ming (2019)

The ‘Greater Council’ (Oobanken in Japanese) is a crow-like cuckoo that is widespread in Asia. A weak flier, it spends most of its time in solitude poking around in vegetation. Its deep call is associated with omens, and its flesh was once eaten as a cure for tuberculosis.

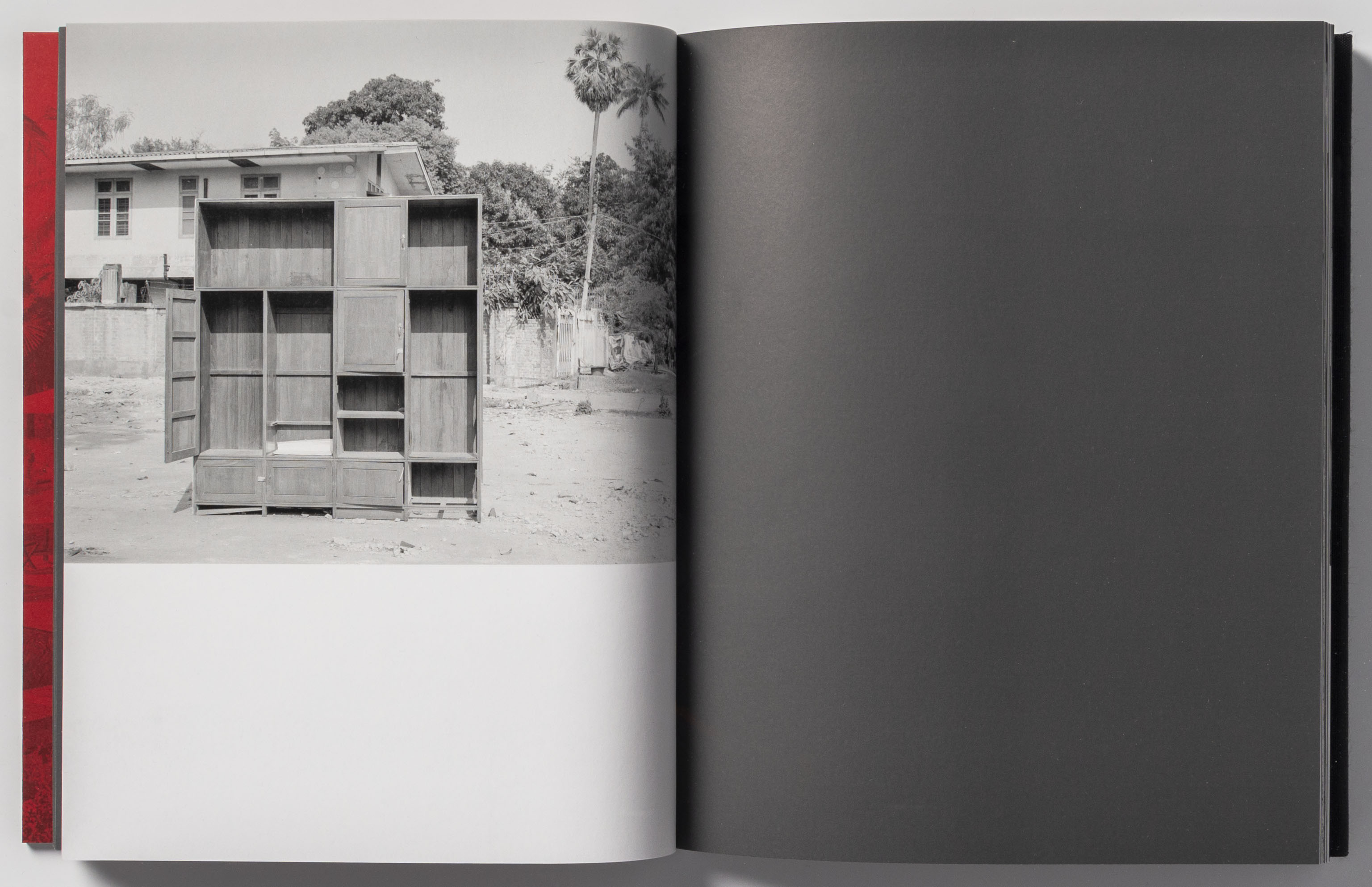

Jerome Ming inhabited the spirit of this bird in his 2019 book Oobanken. While living a largely solitary life in Myanmar, Ming clambered about in the urban underbrush constructing temporary sculptures. Ming’s calls are as abstract as the “oop-oop-oop” of the Oobanken, but just as full of soulful mystery.

See selections from Oobanken by Jerome Ming HERE.

The (virtual) Lunch Table:

Ethan: I’m binge watching Curb Your Enthusiasm right now. Never a poor decision. 8/10

Peter: I recently watched A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood starring Tom Hanks. Hanks’ portrayal of Mr. Rogers reminded me of the value of slowing down, particularly in this time of uncertainty and chaotic energy. 8.5/10

Molly: I am reading on the art and life of El Anatsui a Ghanaian sculptor who creates textural pieces using recycled metal bottle tops and covers. I remember seeing his piece Hovor II (2004) in the de Young with my dad when it was first installed, an exciting and fascinating experience at such a small age. 9/10.

Ky: Last week I went to see Harriet Bart’s exhibition, Abracadabra and Other Forms Of Protection. She had quite a variety work and I especially liked the various ways she represented and honored anonymous workers of different trades. 9/10

Alec: I’ve been watching the Indian police thriller Sacred Games on Netflix. 7/10