I quit the saxophone in 8th grade. No musical talent whatsoever. I continued collecting records throughout high school, but when compact disks took over, I sold them all in frustration. I’ve only been a casual music fan ever since. This has proved problematic when I’m asked to discuss the musical influences on my photography. I can link a few songs to certain projects such as I did with this recent Spotify list, but the connection is tenuous. When traveling alone, it’s just as likely that I’ll be listening to public radio news as a road trip playlist. Fortunately I’ve had the opportunity to work alongside some folks with deep reservoirs of musical knowledge. Rebecca Bengal’s essay is in this newsletter is proof positive.

The one way I talk about photography’s relationship to music is by genre analogy. A friend of mine hates “New Formalism” photography. I’ve suggested she think of that genre as functioning like techno while her work is more like punk. Different genres serve different moods. Just as one might not want to listen to Nine Inch Nails on a rainy Sunday morning, it’s hard to party to Simon & Garfunkel.

As for myself, there’s sadly no getting around the fact that I’m the photographic equivalent of a straight/white/male singer-songwriter. I just hope I’m a little more Will Oldham than James Taylor. With that in mind, I’m happy to finally release the Little Brown Mushroom song. It was written and recoded way back in 2013 by Al James in exchange for my cover art on the Dolorean album “Unfazed.” You can listen to “Little Brown Mushroom” HERE.

In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: LANGSTON HUGHES by Kevin Young

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Who Goñ Bring You Chickens When I’m Gone?

- Ex-Libris: Roy DeCarava

- Archive Dive: Texas Eagle & Sunset Limited

- The Lunch Table

Picture & Poem:

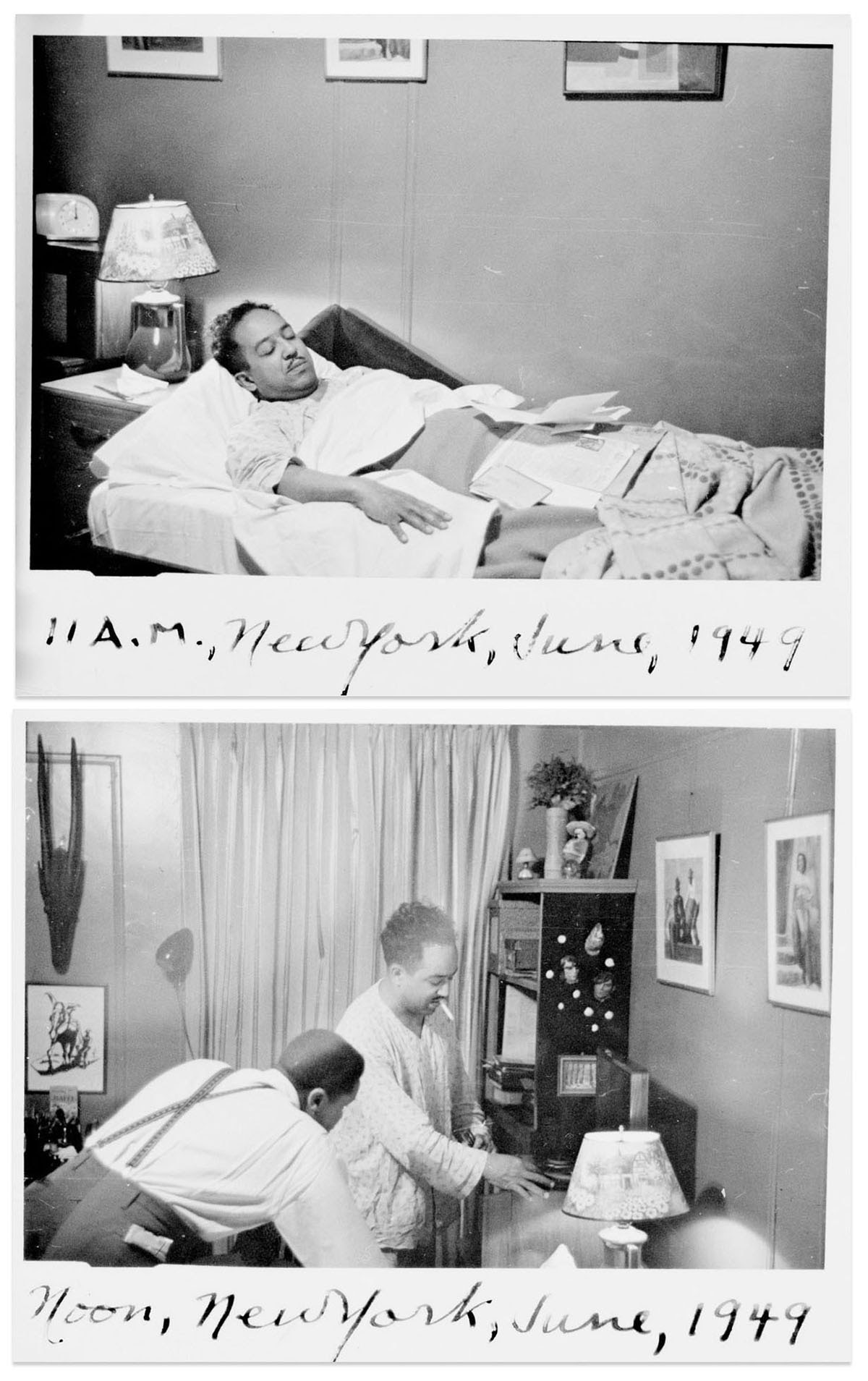

Poking around the Beinecke Library archives, I came across these two photographs of Langston Hughes. No other information accompanies them besides their hand-scrawled captions, which only add to their mystery. It’s hard to know why the time was noted on each photograph, particularly when the clock clearly reads noon in the first image. But I love how the timestamp gives the pictures a Duane Michals-like narrative quality. Having been roused after a late night of writing, Hughes lights a cigarette and puts on a record. One can look at Hughes’s list of 100 favorite recordings (also on Spotify) and imagine what he’s playing.

Who is the younger man in the photo? I’m imagining it is the contemporary poet Kevin Young visiting him in a dream. Named the poetry editor of the New Yorker in 2017, this was Young’s first poem published in the magazine back in 1999:

LANGSTON HUGHES

by Kevin Young

LANGSTON HUGHES

LANGSTON HUGHES

O come now

& sang them weary blues –

Been tired here

feelin’ low down

Read

tired here

since you quit town

Our ears no longer trumpets

Our mouths no more bells

FAMOUS POET©–

Busboy––Do tell us of hell–

Mr. Skakespeare in Harlem

Mr. Theme for English B

Preach on

kind sir

of death, if it please–

We got no more promise

We only got ain’t

Let us in

on how

you ‘came a saint

LANGSTON

LANGSTON

LANGSTON HUGHES

Won’t you send

all heaven’s news

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Who Goñ Bring You Chickens When I’m Gone?

Like you I miss music played live, I miss music played on dingy stages where the floor was like to fall out under your feet, I miss music played in cavernous spaces and small sweaty crowded rooms. Long before I set foot inside any of them, music was remote, distant, yet strangely physical, attaching itself to other spaces where I heard it first: country-singing guest stars of Hee Haw affixed to my grandparents’ kitchen linoleum, Springsteen and Madonna and Prince and Michael Jackson to a boombox propped by a swing set, Run-DMC linked to the backseat of the family Chevrolet, Patsy Cline lodged in the bedroom of a little mountain cabin where a gun stayed tucked under a pillow. Music was faraway then, a tinny dream, a sound bouncing off the wall, reverberating, echoed, absorbed.

Unbeknownst it was all around me too. You’d think, in a tiny town like the one I grew up in, they’d make more of a big deal about one of their very own going off and producing records for Motown, how Johnny Bristol’s voice is the lone male backing up the Supremes on “Someday We’ll Be Together,” how he released his own ode to our shared town. On the outskirts of town, I’d learn, decades later, there’d been little juke joints all over, places called the Ponderosa and the Sundown and the Tombstone, rough and secret places where Little Royal once allegedly played, Sam and Dave too. I didn’t know it then either but the legendary Piedmont blues guitarist Etta Baker lived a mile away from my childhood home; got up with the birds every morning and played the old-time way her father had taught her since her first lessons in 1914 at the age of three.

Another rumor, surfacing among the national obituaries that appeared in the wake of Etta Baker’s passing in 2006 at age 93, was this: “According to legend,” wrote People, “Bob Dylan met Baker around his 21st birthday and was inspired by her style to write “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” How good a story—too good a story, I thought, if my own favorite song of Dylan’s had even in some cracked-up, roundabout way been influenced by the place I came from too. There’s certainly a spiritual relationship between the peripatetic finger-picked guitars that move below the surface of Dylan’s song, and Etta Baker’s knifeblade-slide picking, particularly on “Railroad Bill” and “John Henry”—the old songs and ancient chords she made her own. But it was another thing to picture Bob Dylan making a special trip to a town I spent my teenage years longing to escape.

“It’s a hard song to sing,” Dylan says in Nat Hentoff’s liner notes for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. “I can sing it sometimes, but I ain’t that good yet. I don’t carry myself yet the way that Big Joe Williams, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, and Lightnin’ Hopkins have carried themselves…. You see, in time, with those older singers, music was a tool—a way to live more, a way to make themselves feel better at certain points. As for me I can make myself feel better some times, but at other times it’s still hard to go to sleep at night.”

“Have you been able to find out if the Bob Dylan story is true?” David Holt, host of the PBS series Folkways, asked me when I called him about Etta Baker. I told him I was working on it. Said I’d have to go back pretty far.

***

Start with the song itself, the legend that prompted it. The real Railroad Bill was a circus hand and turpentine worker named Morris Slater, who robbed freight trains in Alabama and Florida in the 1890s and shot anyone who tried to stop him. “I love you and do not want to kill you so do not come after me,” he is said to have written to one local sheriff who set out to capture him (two sheriffs before had not been so lucky). The mythic Railroad Bill did not need to shoot any sheriffs because his shapeshifting abilities allowed him to run from the law. He’d been shot so many times and survived, legend went, that the only fire that could kill him was a solid silver bullet. And he’d live many times over in song.

“Railroad Bill,” ballad of a tale of a folk hero endowed with supernatural powers, was first collected around 1912 by Josh White, Perrow, and Odom; it survived a world war, a pandemic, and just before the start of the Great Depression, it was included in The American Songbag, a now classic anthology of folk music, collected by Carl Sandburg who dedicated the book “[t]o those unknown singers—who made songs out of love, fun, grief—and to those many other singers—who kept those songs as living things of the heart and mind out of love, fun, grief.” Sandburg’s songbook was a book, he wrote, “for sinners and for lovers of humanity.” He stipulated that “Railroad Bill” was to be played moderato: “The verses couple onto each other like fast mail coaches. Singers hesitate nowhere and stride through this with the clip of a non-stop train.”

“Railroad Bill” was likely one of the songs a 43-year-old Baker was playing on the porch of a historic mountain home in North Carolina in 1956 when she was coincidentally overheard by a particularly like-minded group of tourists passing through the area: Paul Clayton, a Greenwich Village-based dulcimer musician and song collector who became a mentor to Bob Dylan; Liam Clancy, the youngest member of the Irish folk group the Clancy Brothers, then just a boy troubadour on his first trip to America; and Diane Hamilton, née Guggenheim, who as a child was kept on virtual lockdown for fear she’d be abducted like her neighbor Charles Lindbergh, Jr. She grew up, changed her name, started a folk label—Tradition Records put out records by Lightnin’ Hopkins and Odetta and Jean Ritchie—and put out records by both Clancy and Clayton.

Picture Justin Timberlake’s character in Finding Llewelyn Davis: Paul Clayton was the Coen Brothers’ model for that role, at least visually. Clayton “mingled the role of the Massachusetts Bay young salt, ragged but right, with the beau ideal of the Virginia gentleman: gracious, sardonic, with occasional duplicity thrown in,” writes his biographer, Bob Coltman. “The seesaw between a glad Galahad and a low-dive crapshooter persisted as a theme in his life.” He still kept the backwoods cabin he’d rented in his days at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, using it as the home base for his song collecting trips. Clayton had romantic relationships with men and women; he liked pills; he liked to drive old cars deep in the hills and collect the music he loved, sailing over rutted roads and hiking swinging bridges with his microphones and recorders to talk his way into strange houses. He’d convinced Hamilton and Clancy to drive down from New York on of these road trips and it was by pure accident that they chanced to pull over and tour the Cone mansion in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina on a day when Etta Baker’s husband had talked the proprietors into letting her sit on the porch and play.

Clayton, awestruck by Baker’s finger-picking, made plans to go to Baker’s home the next day. Baker, a textile worker by trade, shushed her nine children as this trio of strangers set up a makeshift recording studio in her living room. The result was her and her father and sister’s contribution to Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians, which was released on Hamilton’s Tradition Records and quickly moved through the Village folk scene and into college towns where Baker’s North Carolina Piedmont blues compatriot Elizabeth Cotten, Sleepy John Estes, Roosevelt Sykes, and Mississippi John Hurt played coffeehouses.

***

Almost certainly Clayton played Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians for Bobby Zimmerman-not-yet-Bob Dylan, soon after he took a Greyhound from Minneapolis to New York in 1961, and set about immersing himself in the Village folk scene and the music that came before. Clayton quickly became both friend and teacher. In 1964 Dylan would tell an interviewer, “Because folksongs are a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful thing, really like the god-almighty arts … [Y]ou have to use it to learn about you, and whatever you want to do…English ballads, Scottish ballads… The only guy I know that can really do it is a guy I know named Paul Clayton, he’s a medium, he’s not trying to personalize it, he’s bringing it to you… [Joan Baez] can do anything beautiful, she has that kind of thing. But Paul, he’s a trance.”

A year before Dylan’s arrival, Clayton had sourced “Who Goñ Bring You Chickens,” a song collected in a book housed at the University of Virginia library, Eight Negro Songs (from Bedford Co. Virginia), whose title was curiously styled with a tilde over the first n. The song was meant to be sung by a man who is going to jail for a six-month sentence, addressed to his sweetheart, Francis H. Abbot, the song collector instructed. Its refrain: “Who gon’ bring you chickens when I’m gone? Aw, bebeh!” In Clayton’s version, “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone)”, he had rewritten the lyrics: “It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why now, darlin’/ Just wonder who’s gonna bring you ribbons when I’m gone.” Around the end of his first year in New York, Dylan went back to Minneapolis for a visit. At his friend Bonnie Beecher’s apartment he recorded twenty-six songs that his friend Tony Glover recorded on reel-to-reel. The complete Minnesota Hotel Tapes, as the bootleg came to be known, include a number of traditional songs, among them the hymn “Wade in the Water,” “Baby Please Don’t Go,” and “Railroad Bill.”

In May 1962, shortly after the release of his first album, Dylan and his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, the CORE organizer who Dylan had fallen in love the previous summer, and Paul Clayton hopped in Clayton’s car and headed south. In Virginia, Suze Rotolo wrote in her memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time, they detoured onto back roads, dropped in on musicians Clayton had recorded, and threw a party at Clayton’s cabin for Dylan’s 21st birthday. The plan had been to drive down to Morganton, North Carolina, Rotolo wrote, much as Clayton, Clancy, and Hamilton had done six years earlier. “We hoped to visit Etta Baker, the great blues guitarist famous for her song ‘Railroad Bill,’ but it never happened. To impress the folkies back in New York, Bob joked, we should say we met her anyway, but we never did. You could blow your cool by not being cool about things like that.”

***

That summer, Rotolo went with her family to Europe and by fall, she chose to stay on in Italy, leaving Dylan alone and brokenhearted in New York. Stephen Wilson, a close friend of Clayton’s at the time, remembers Clayton telling how Dylan picked up a guitar one afternoon and said, “Hey I rewrote your song, what do you think about this?”

Dylan’s lyrics, implacable and gruff—“And ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe / If you don’t know by now” run through a melody awfully similar to Clayton’s: “It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why now, darlin’/ Just wonder who’s gonna bring you ribbons when I’m gone.” Dylan’s song would be covered by Peter, Paul, and Mary, whose version went to number 9 on the Billboard charts; it’s since been covered by Odetta, Johnny Cash, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Dolly Parton, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, Cher, Nick Drake, and Doc Watson. Even as Dylan and Clayton stayed friends, their publishing companies sued each other, eventually settling. But the larger debate it pointed to—the question of who the song belonged to, if it could in fact belong to only one performer—remains unresolved. “Was Paul just the song’s latest carrier? But he’d rewritten it!” Clayton’s biographer Coltman writes. “But Dylan was borrowing from him as if he was a ‘traditional’ source. Was he? Wasn’t he?”

“And it ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe/I’m on the dark side of the road,” Dylan sings, letting a plaintive pitch in his voice register a confession of yearning—“But I wish there was something you would do or say” before he delivers the kiss-off, perhaps directed at Rotolo: “You just kinda wasted my precious time .” “[I]t isn’t a love song,” Dylan is quoted in Hentoff’s liner notes. “It’s a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better. It’s as if you were talking to yourself.”

***

Is there something of Etta Baker’s playing, especially her “Railroad Bill,” that wove its way into “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right”? Could there have been any truth to the rumor of Dylan visiting my hometown? Rotolo, who died of cancer in 2011, had discounted it; Clayton committed suicide in 1967; and Etta Baker died in 2006, at the age of 93. That leaves Bob Dylan among the living witnesses, and thus far, unsurprisingly, he’s yet to confirm or deny the legend of his supposed visit to Baker’s front porch. As far as I’ve found, the tale originated with Clayton’s old friend Stephen Wilson who told Baker’s label, the Music Maker Foundation, a story of the 1962 road trip—how Clayton had taken Dylan and Rotolo to Virginia and North Carolina to visit some blues players for Dylan’s 21st birthday, how they’d visited some blues players along the way; how they drove down to visit Etta Baker.

“I thought it made a great press release,” Tim Duffy of the Music Maker Foundation, told me. “Then I get a call from Wilson saying he’s just gotten off the phone with Suze Rotolo and she says they never actually met her! I told Stephen, I put the whole fucking thing out there already!” The account survives in liner notes and online, and, as a result, in Baker’s obituaries. “You know, Clayton was kind of a raconteur and I think this is once of his essences that went around,” Duffy told me. “It made for a good story either way.” Or, as someone else told me, “That’s why they call it folklore.”

***

In all her recordings of the song, Etta Baker played “Railroad Bill” without singing the lyrics. Shed of its narrative, it is no longer limited to the tale of the murderous, wanted man with his supernatural abilities. It lifts his supposed shapeshifting powers and pulls them into a song that transcends its origin story, resurrects an ancient feeling and interprets it as a sound that defies anything as confining as words.

“The American Songbag,” Carl Sandburg wrote, “comes from the hearts and voices of thousands of men and women. They made new songs, they changed old songs, they carried songs from place to place, they resurrected and kept alive dying and forgotten songs.” The freight-train-hopping vigilante, the scorned lover turning down the road, the jailed man counting the days till he can be set free, and the keeper of the loping, roving rhythm—they share a willful, wandering spirit. “I call it traveling music,” Etta’s son Edgar told me. Below those tough, pride-wounded vocals Dylan and Bruce Langhorne’s guitars forge on, consciously or unconsciously reminiscent of the feeling of Baker’s lilting finger-picking style, down the same long road.

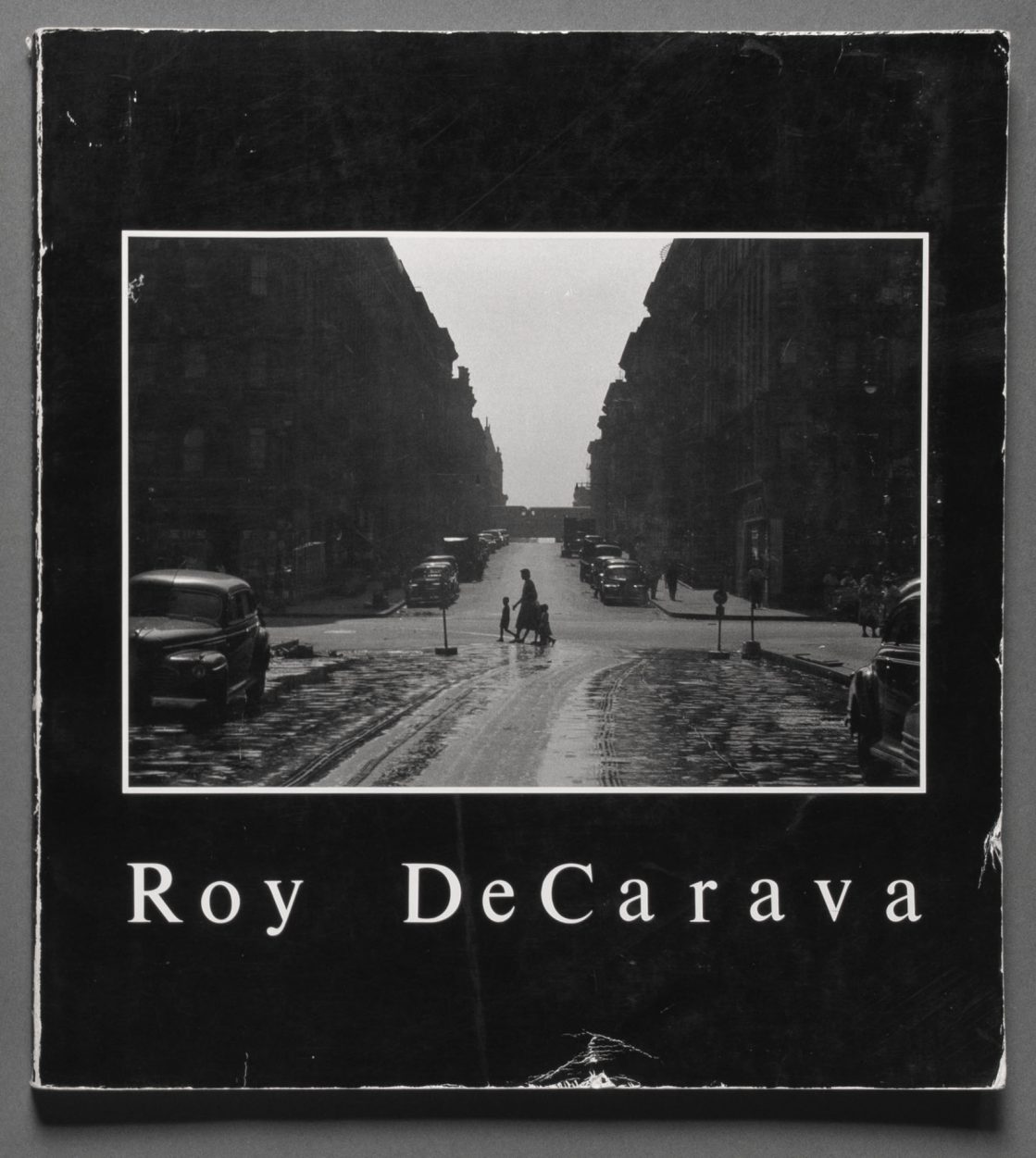

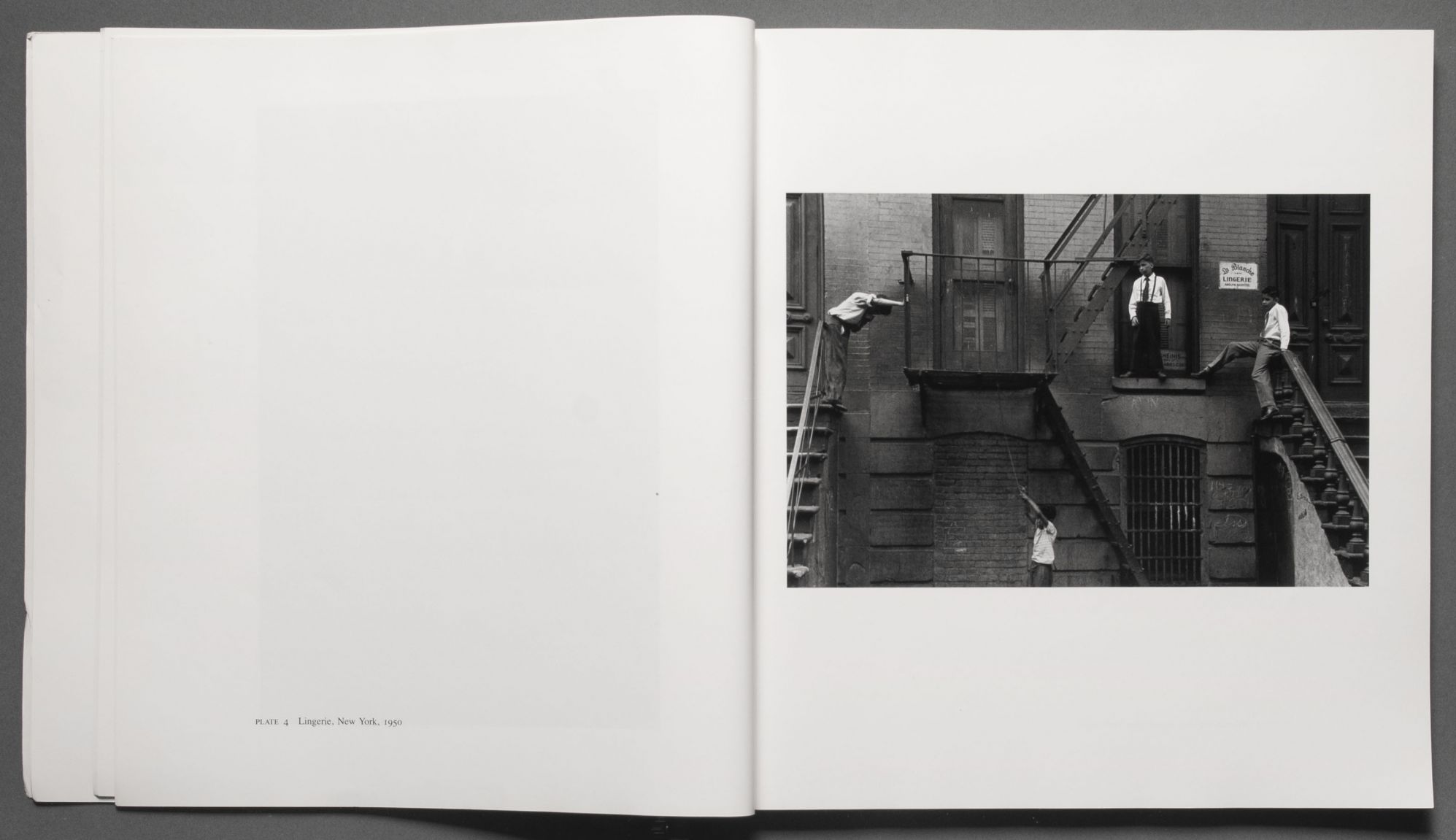

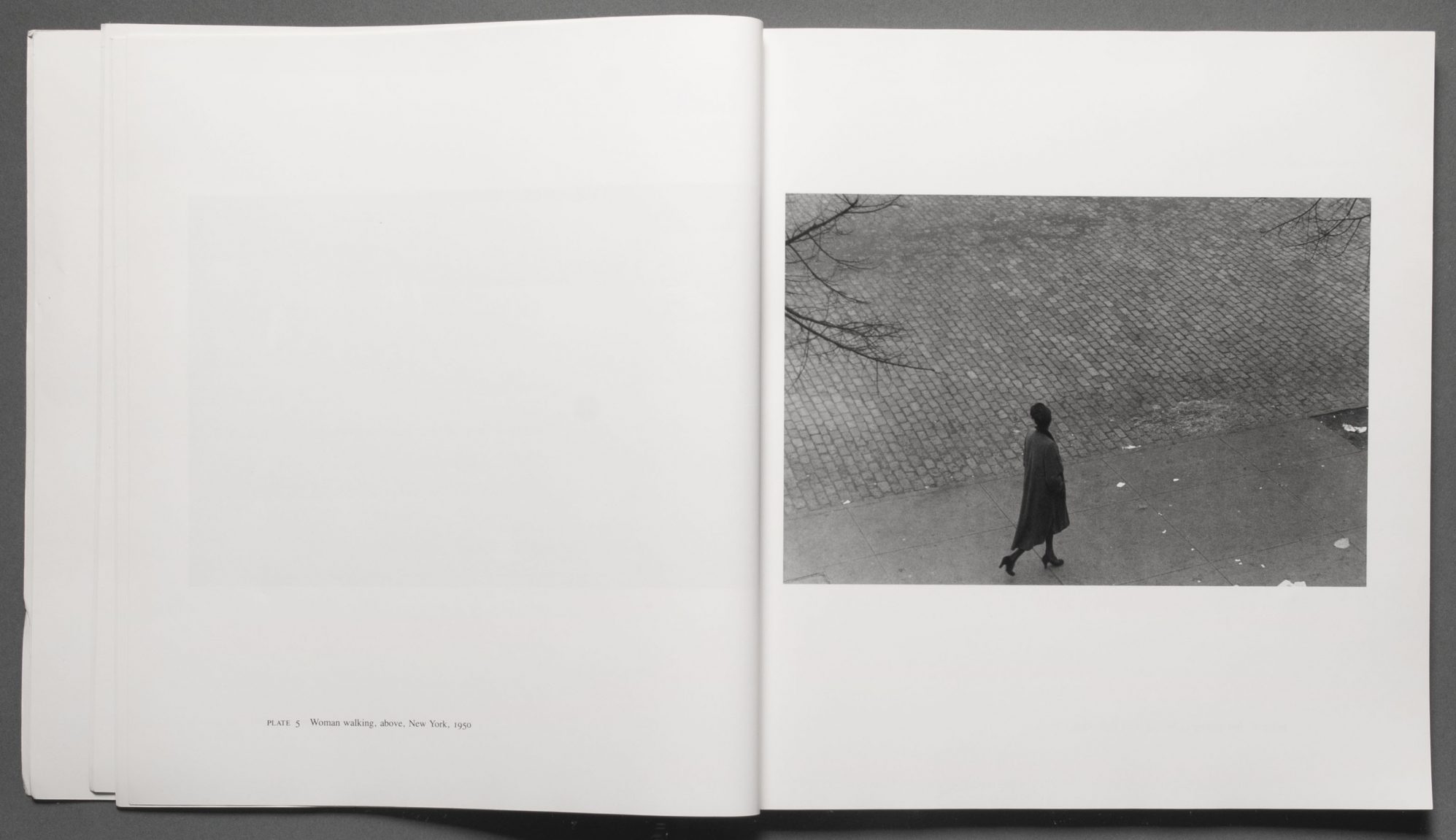

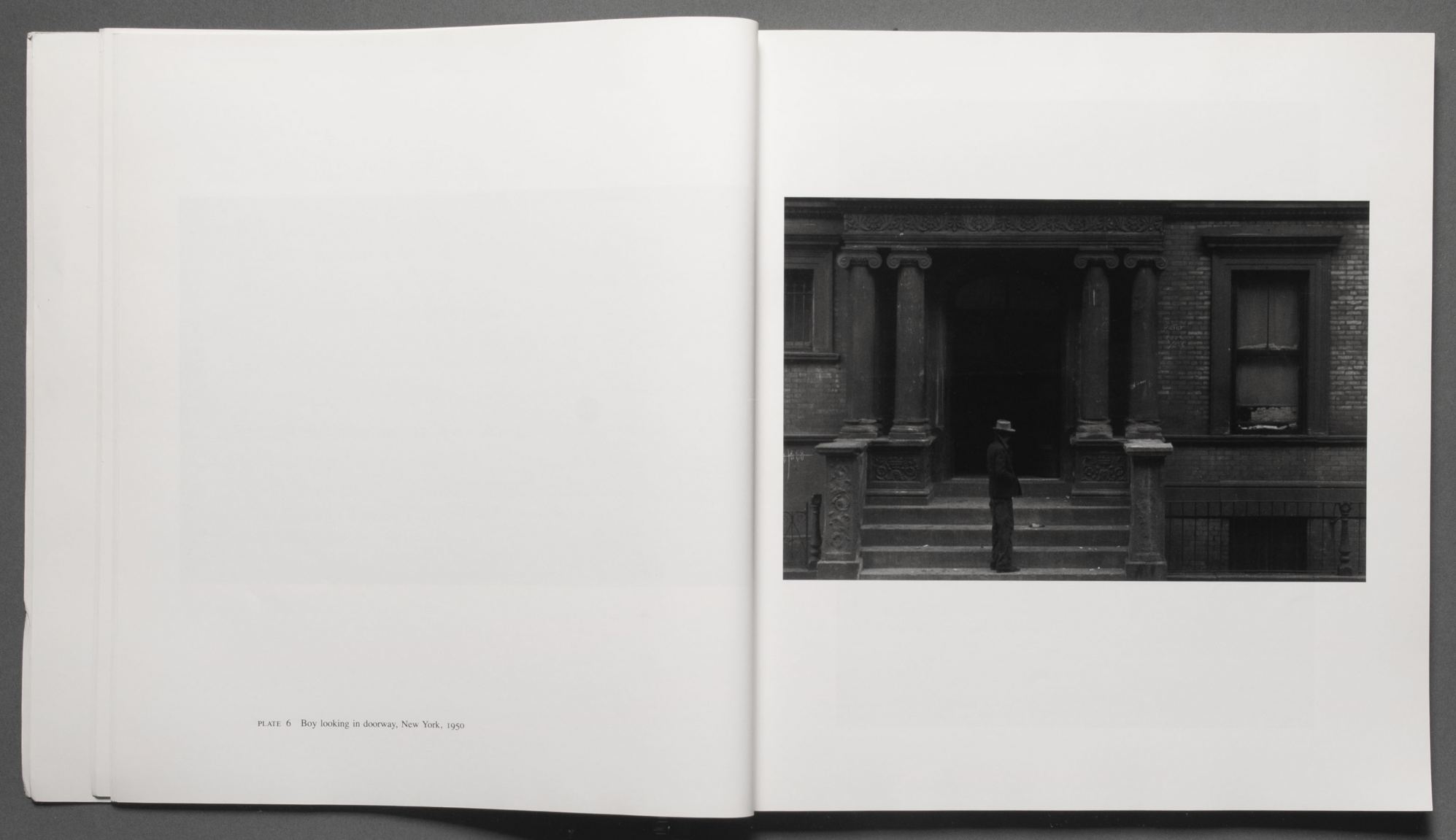

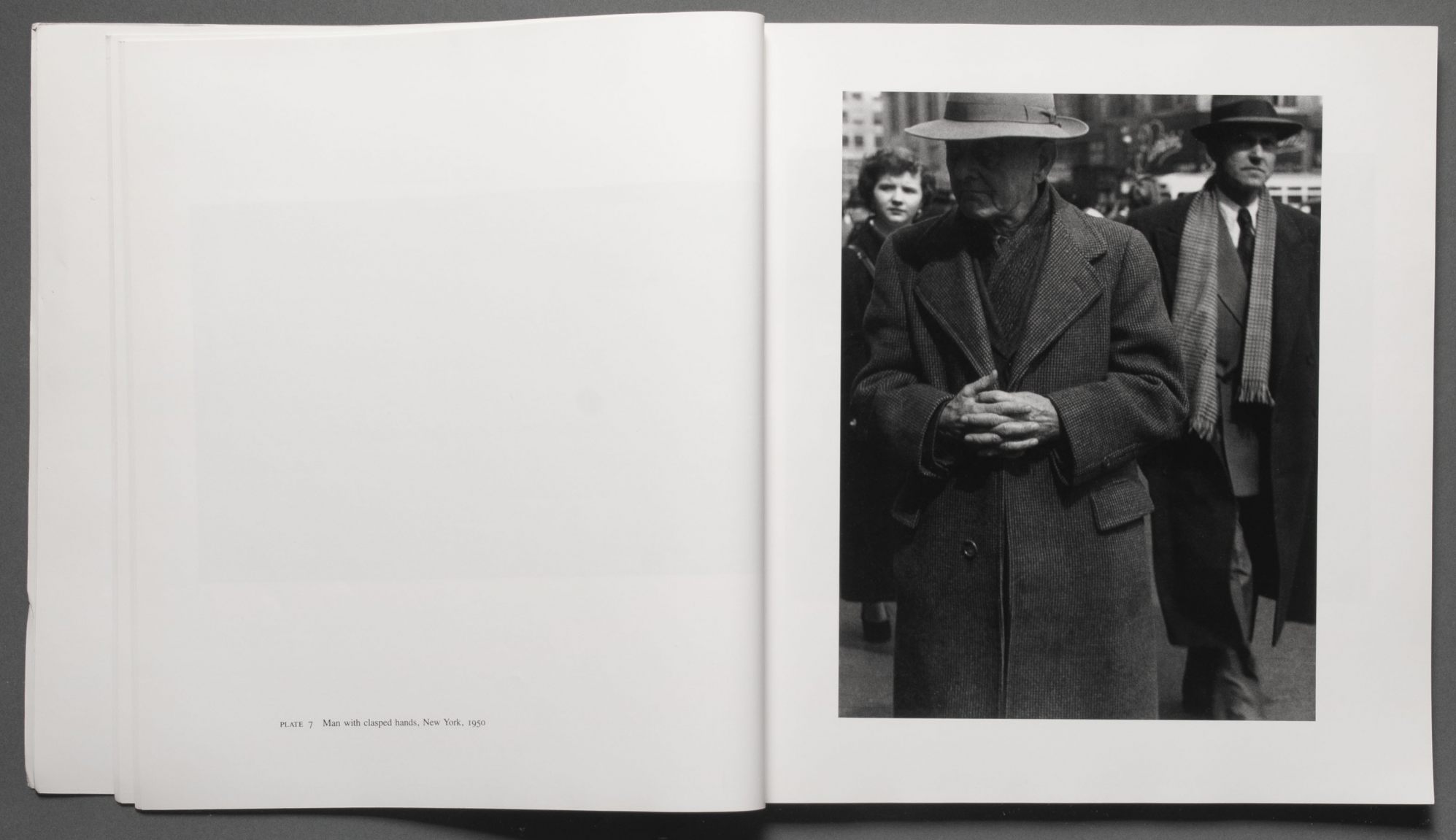

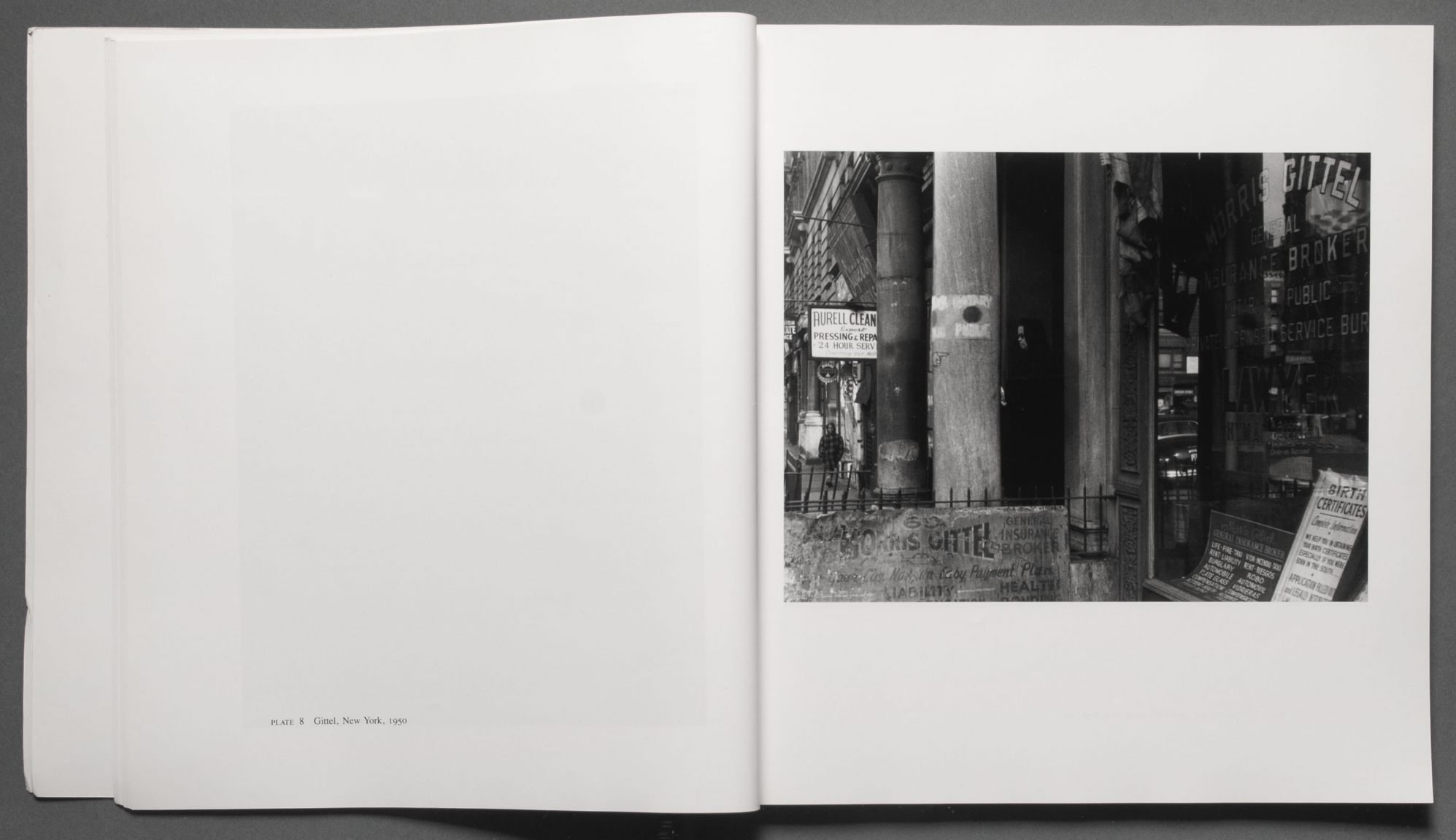

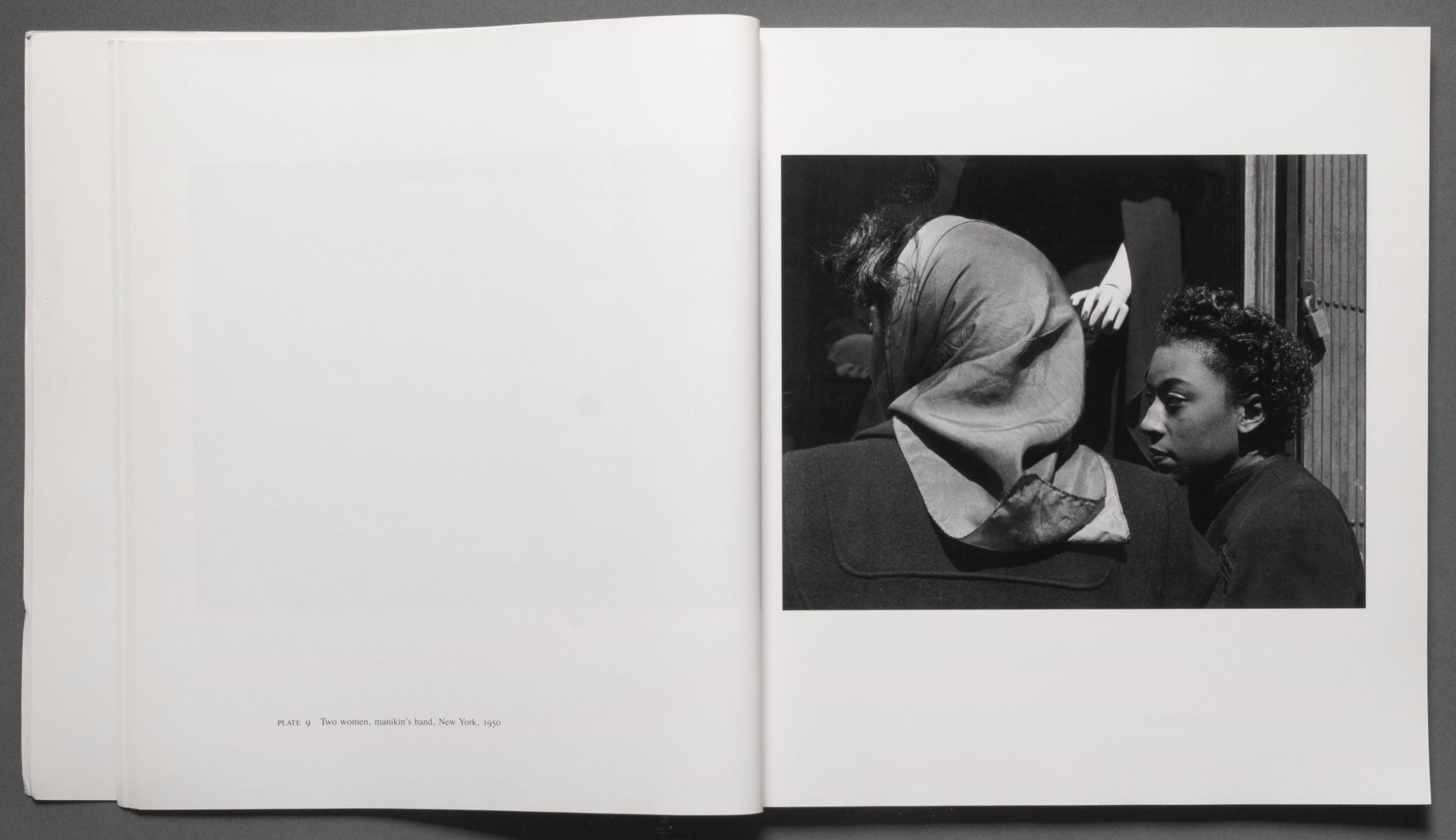

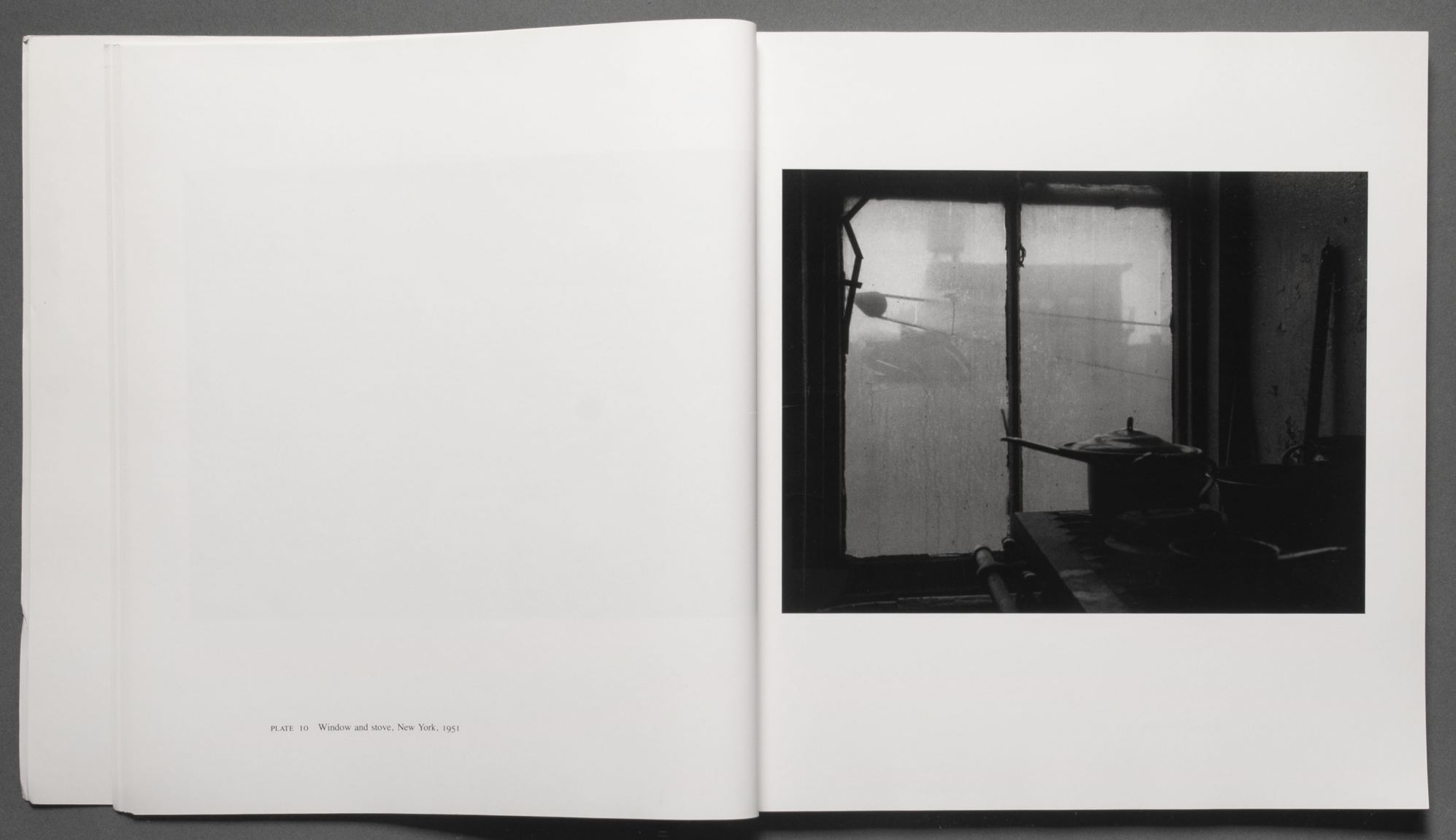

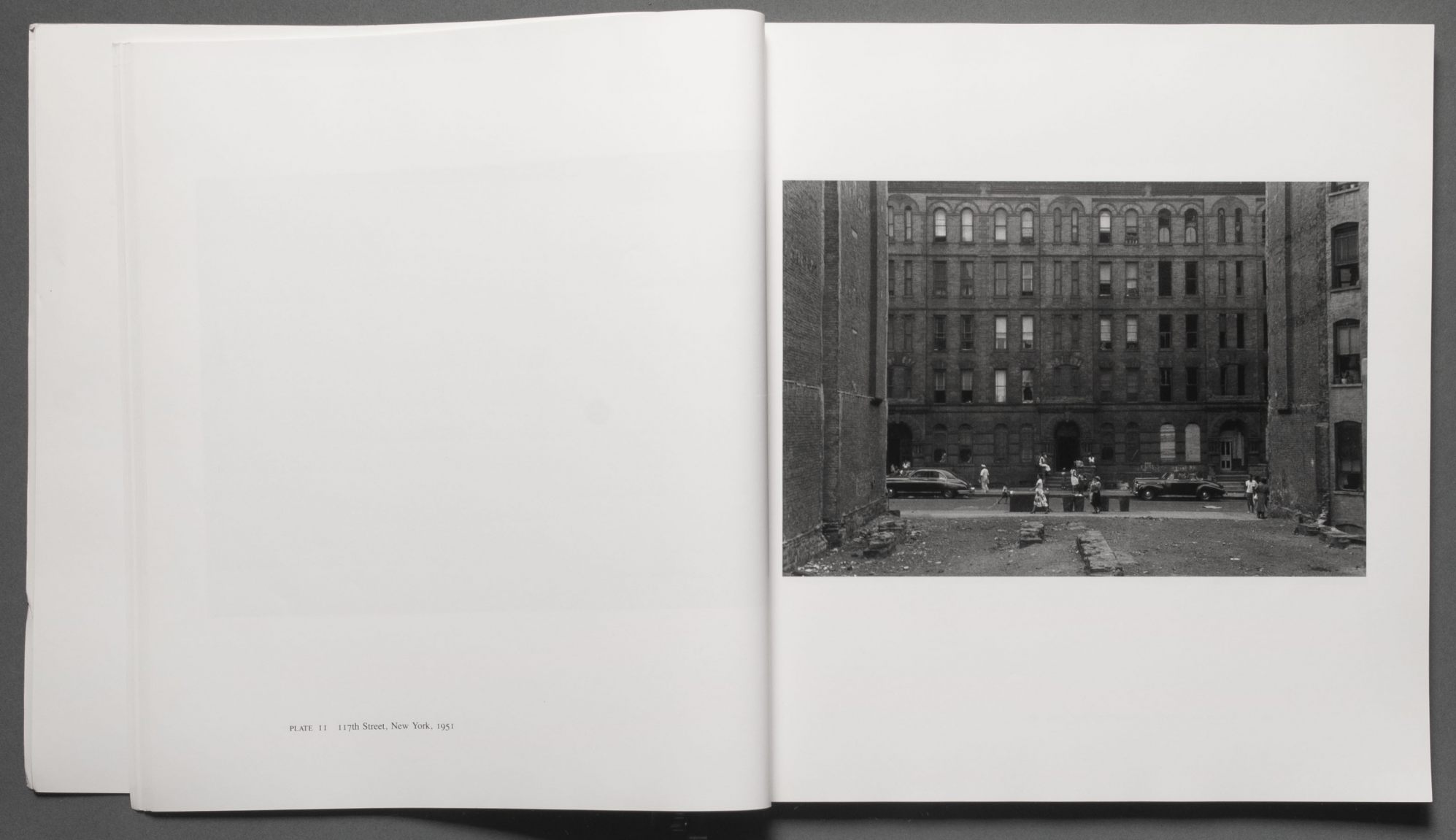

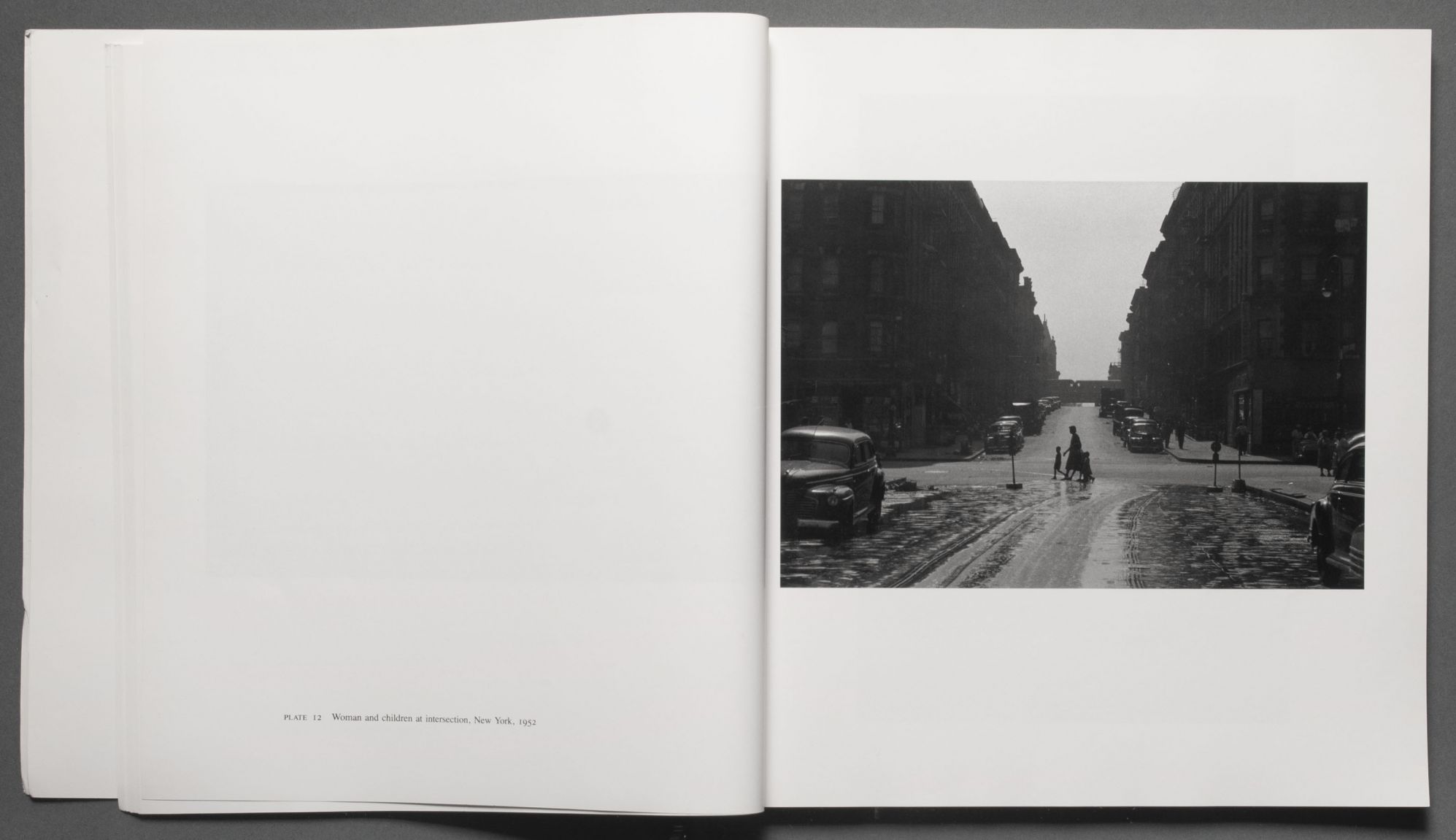

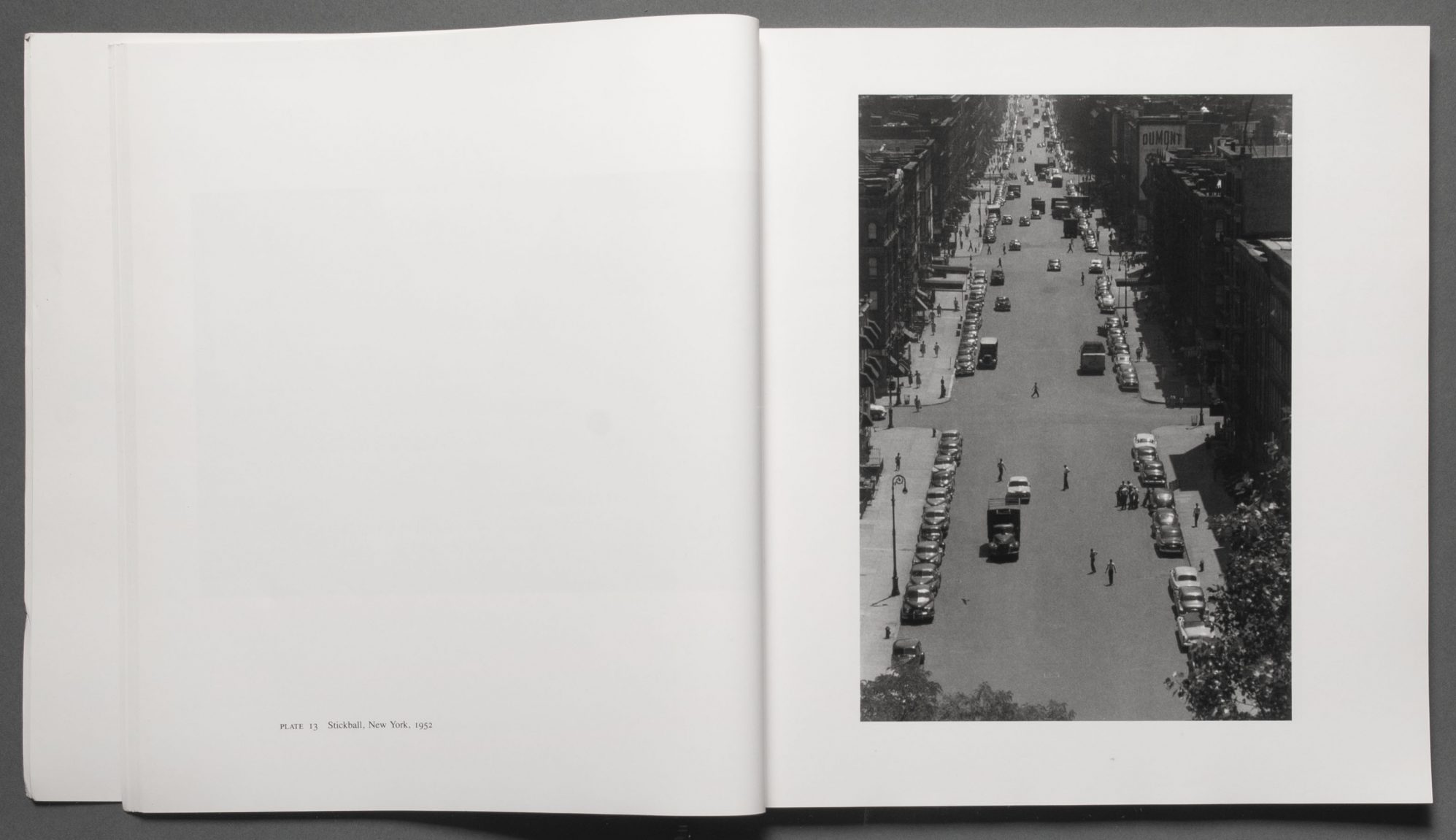

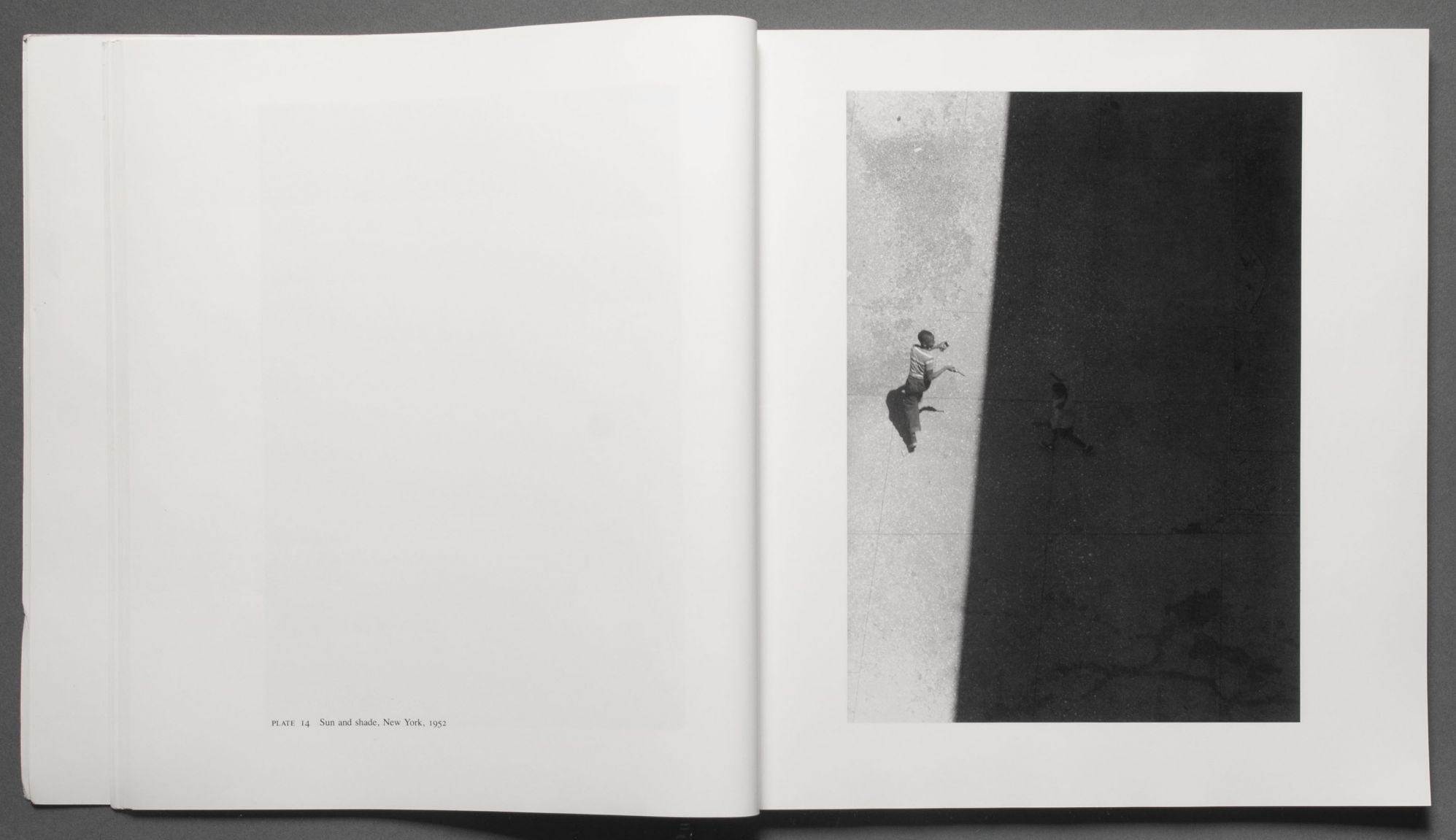

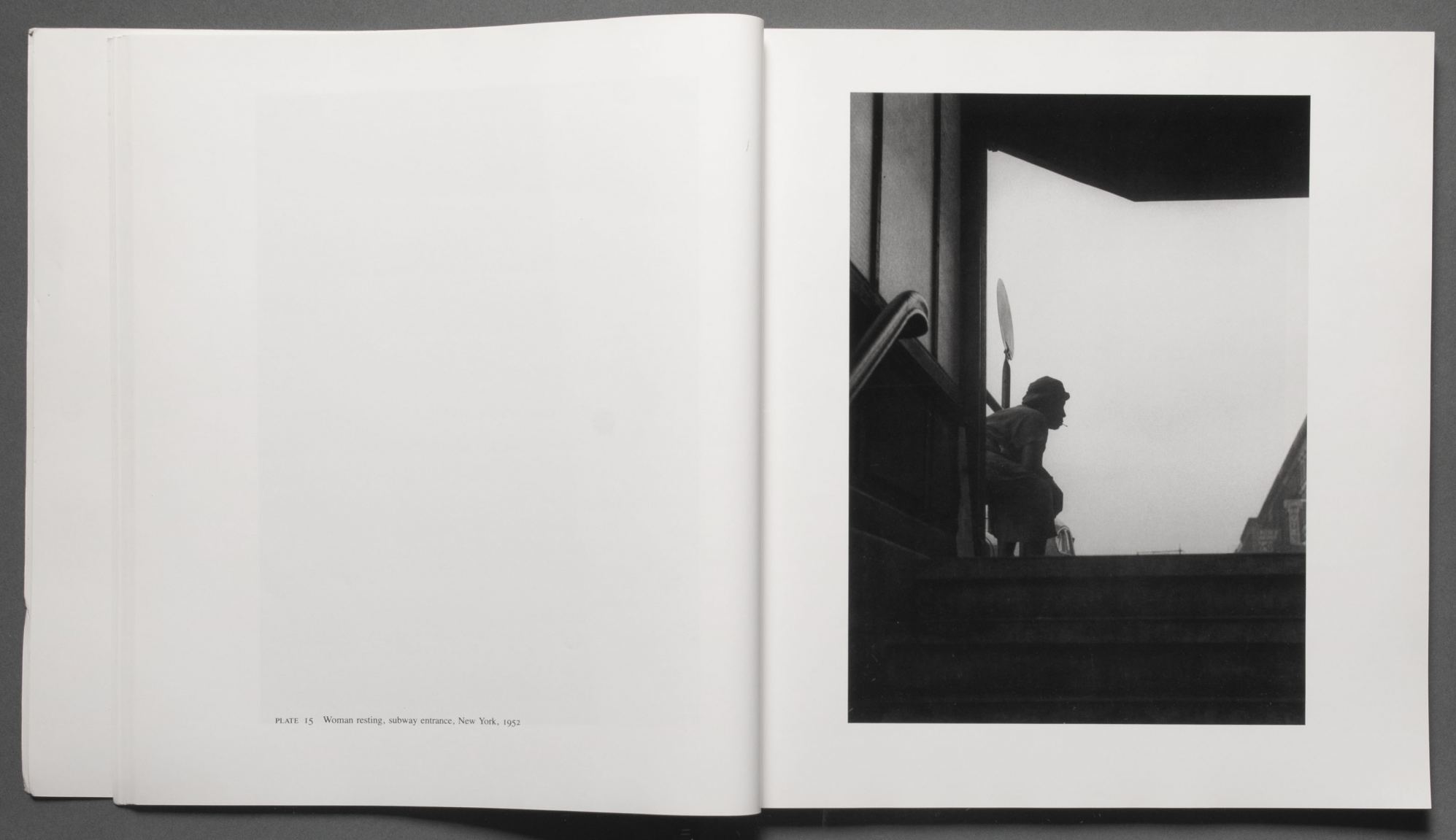

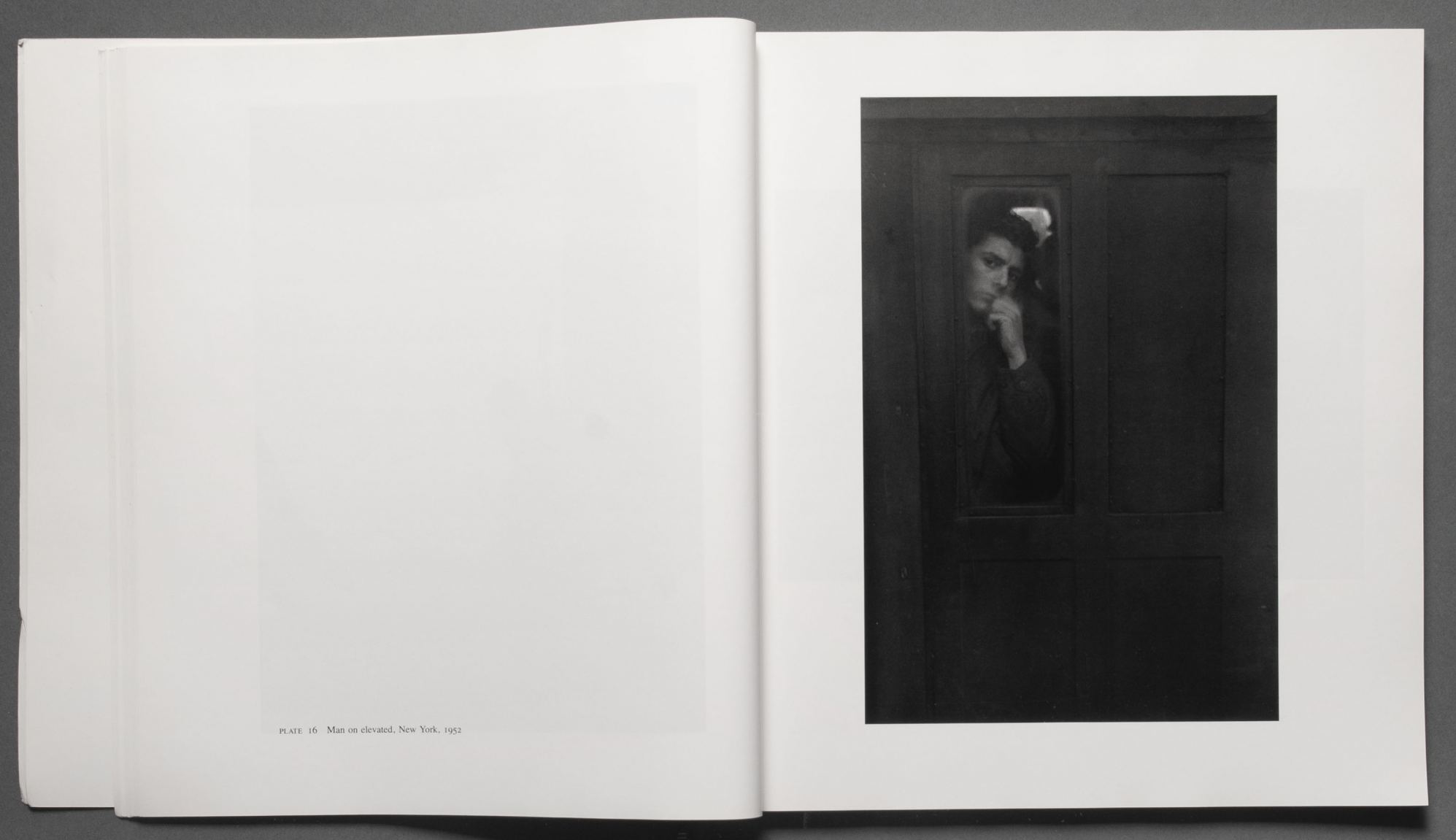

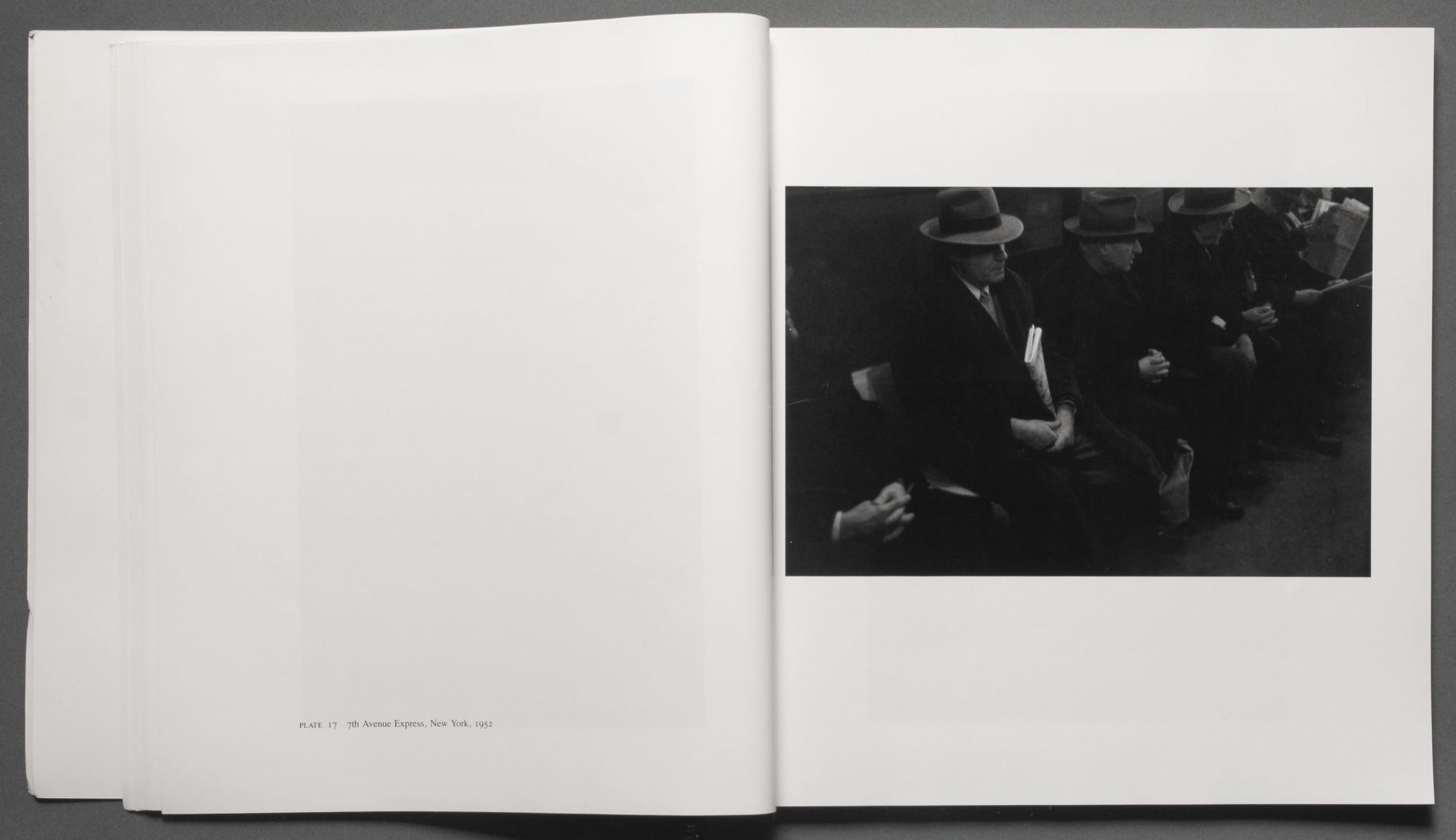

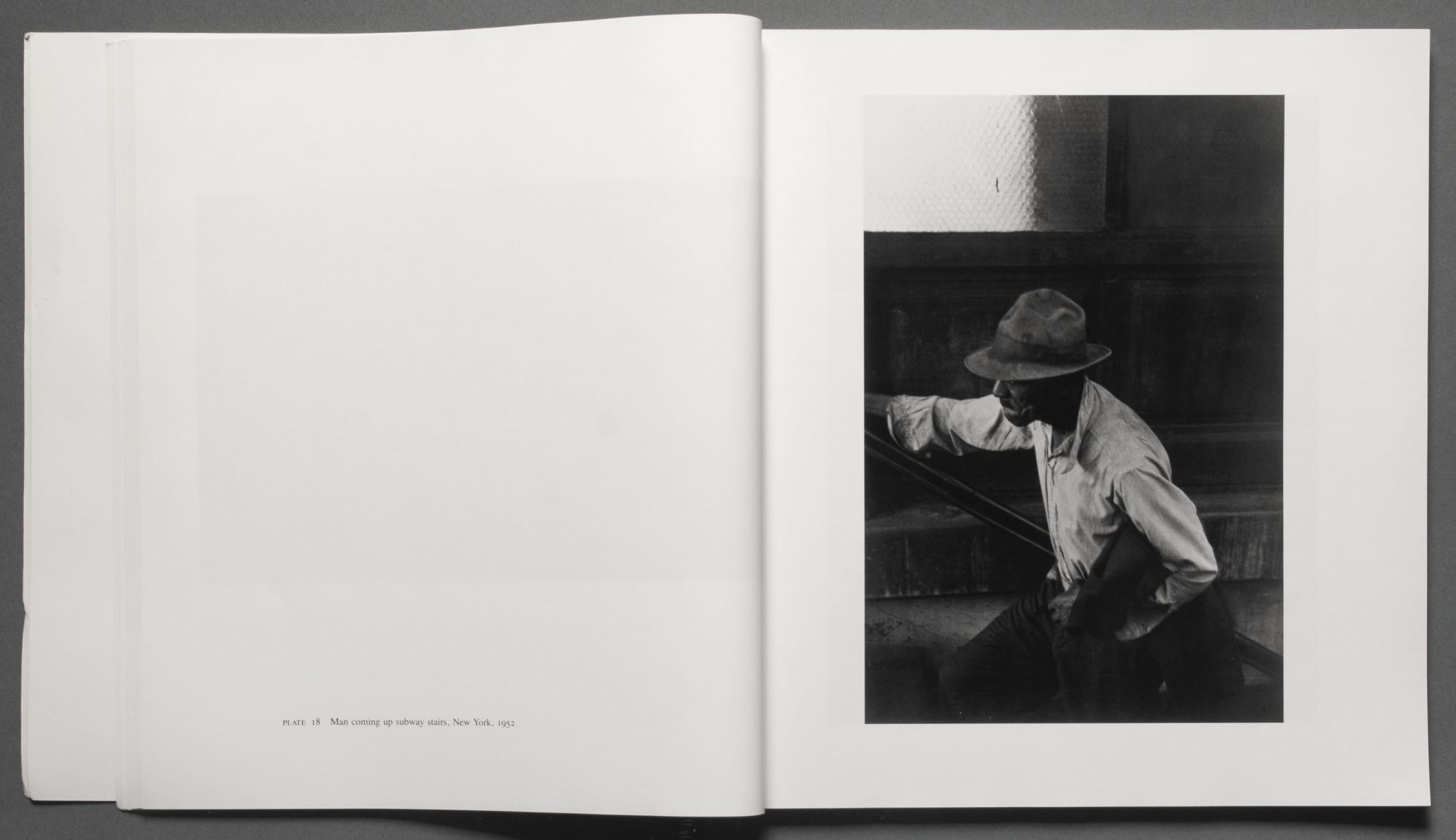

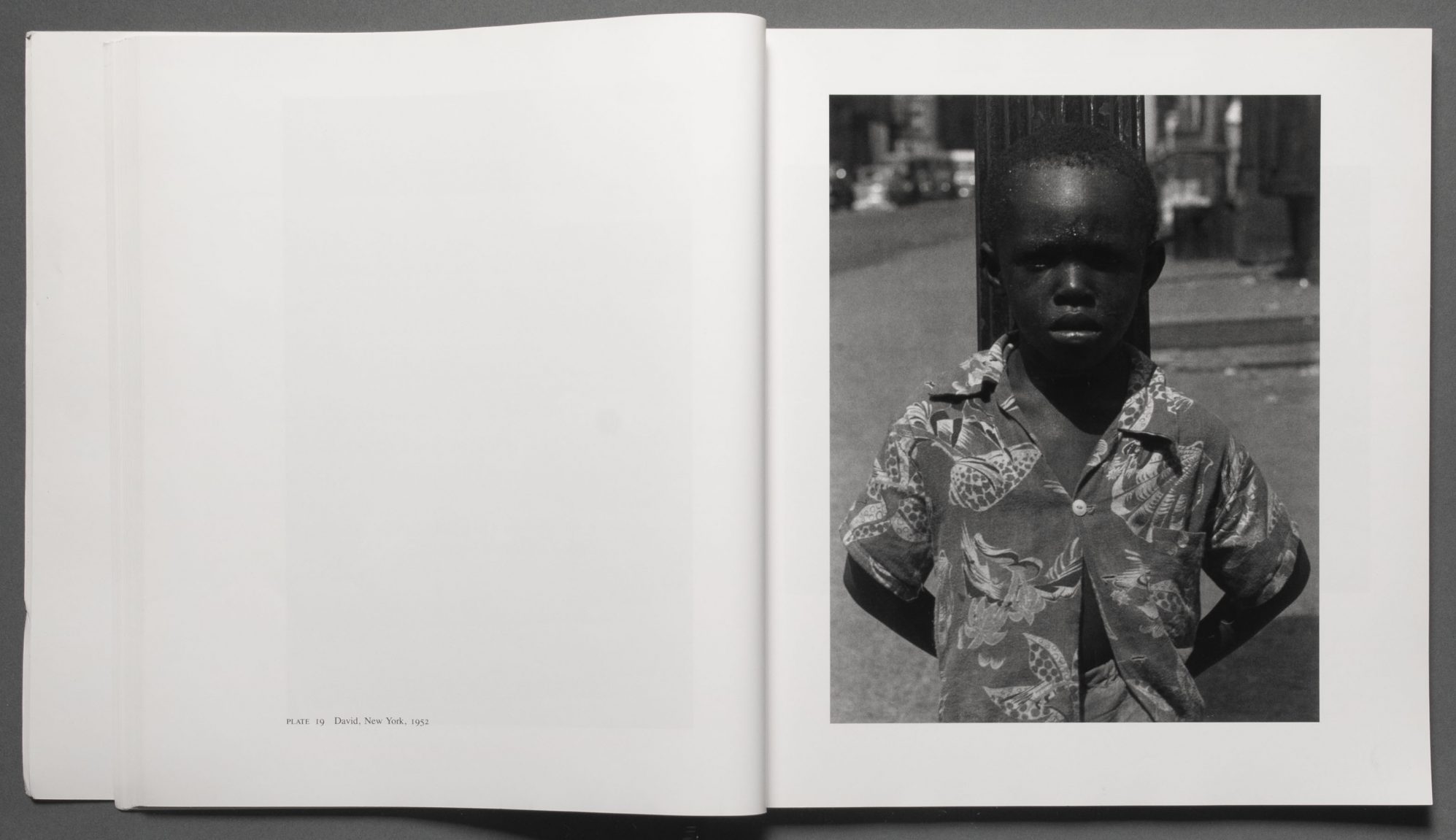

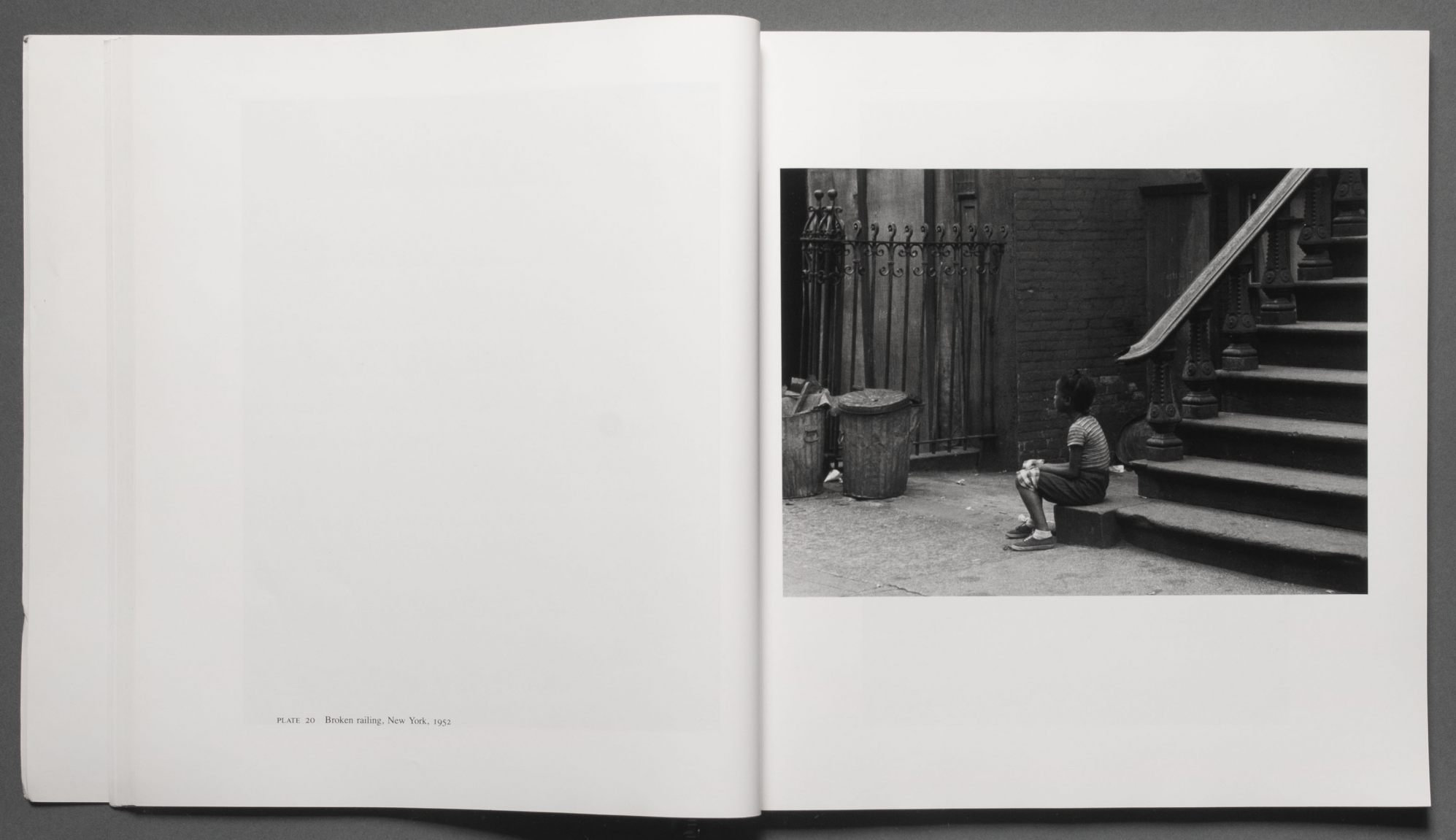

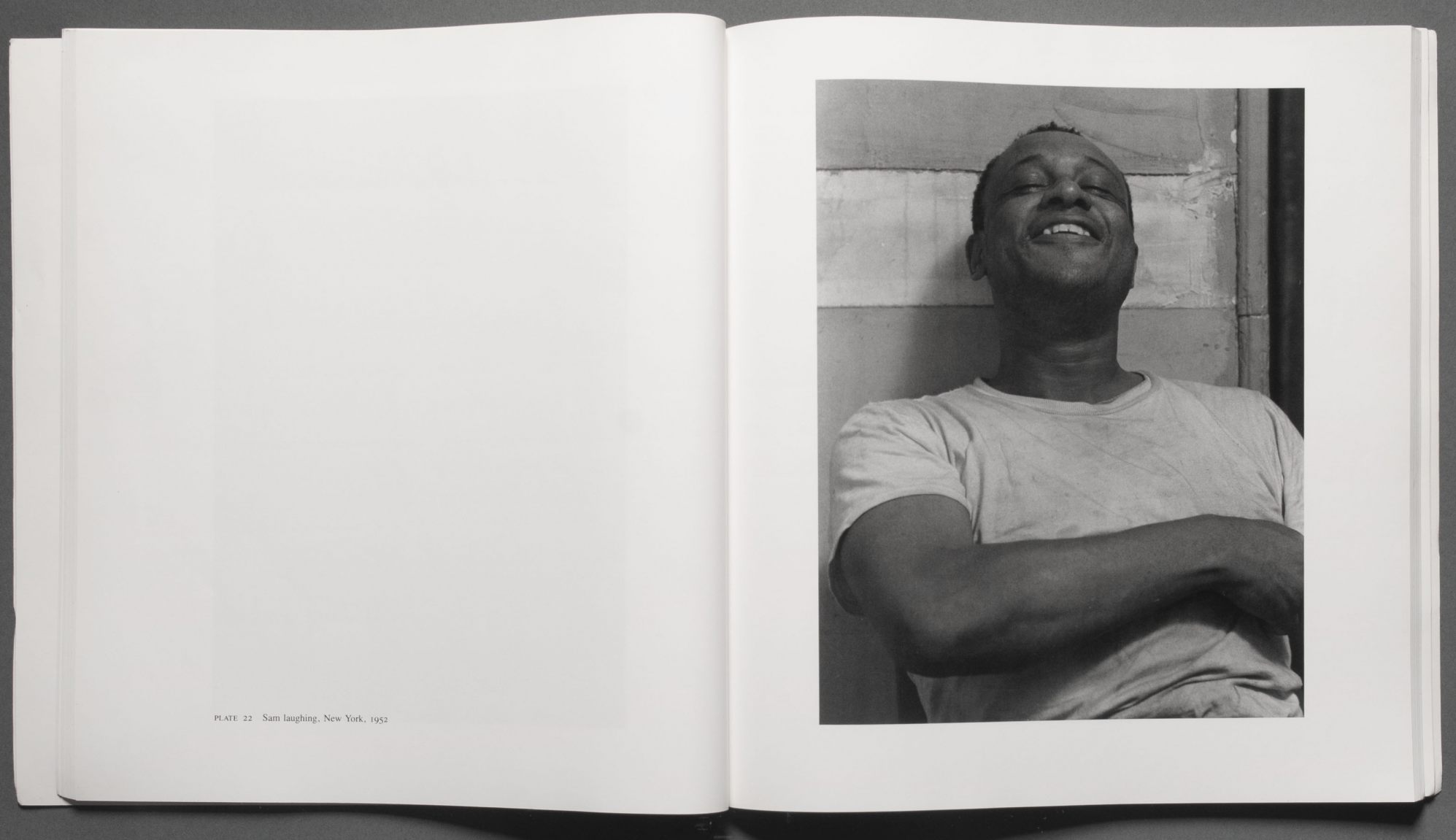

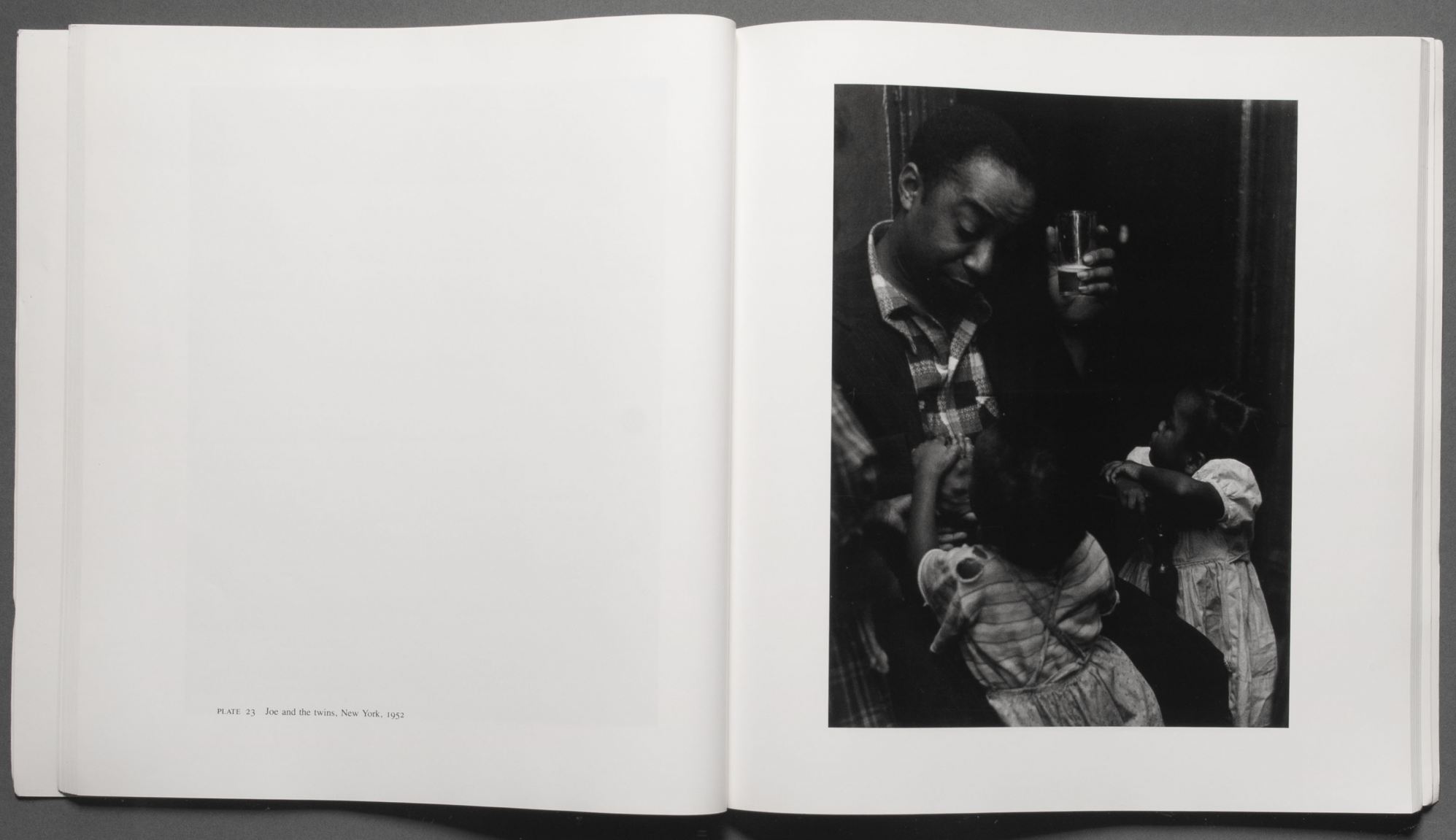

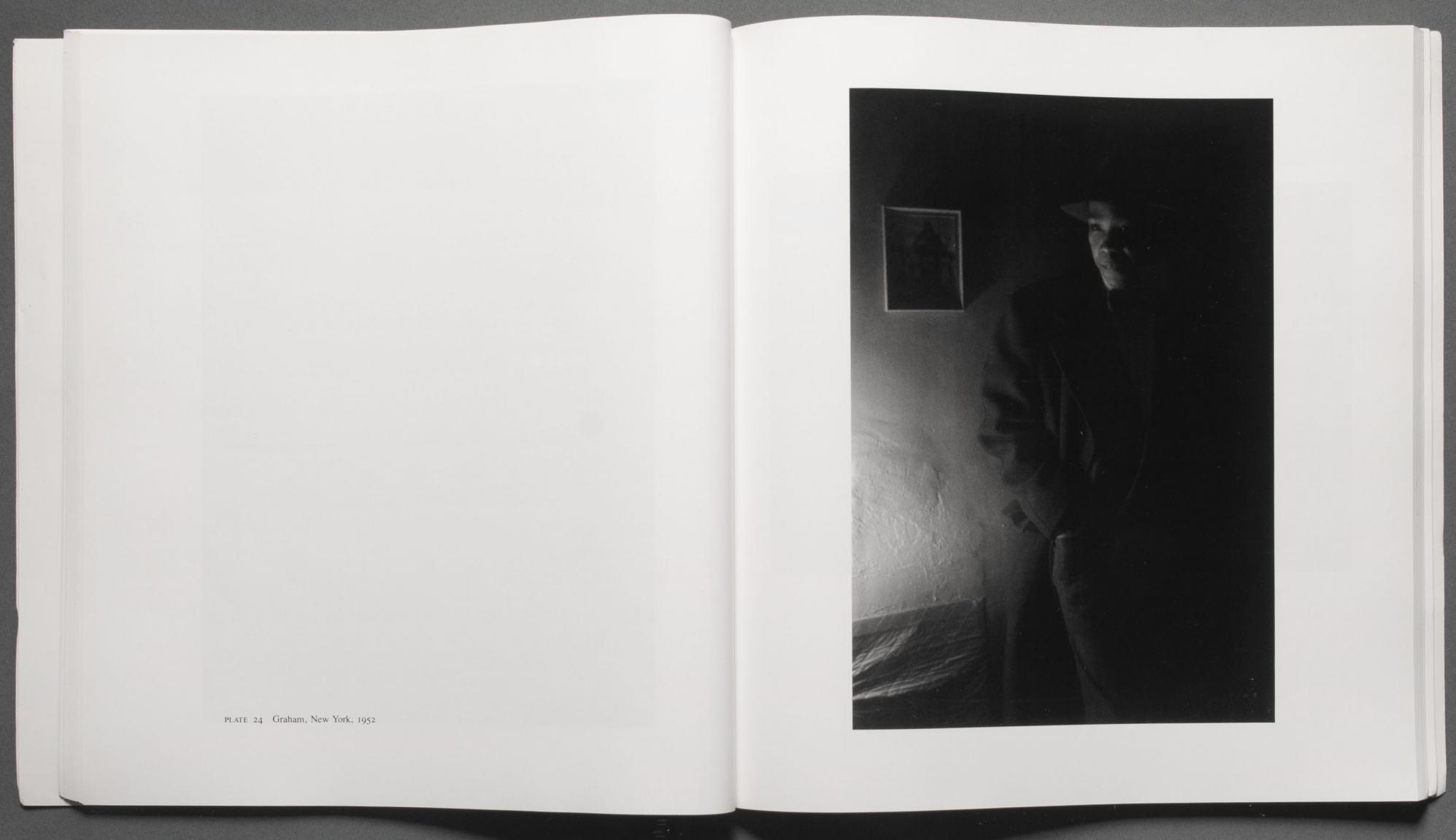

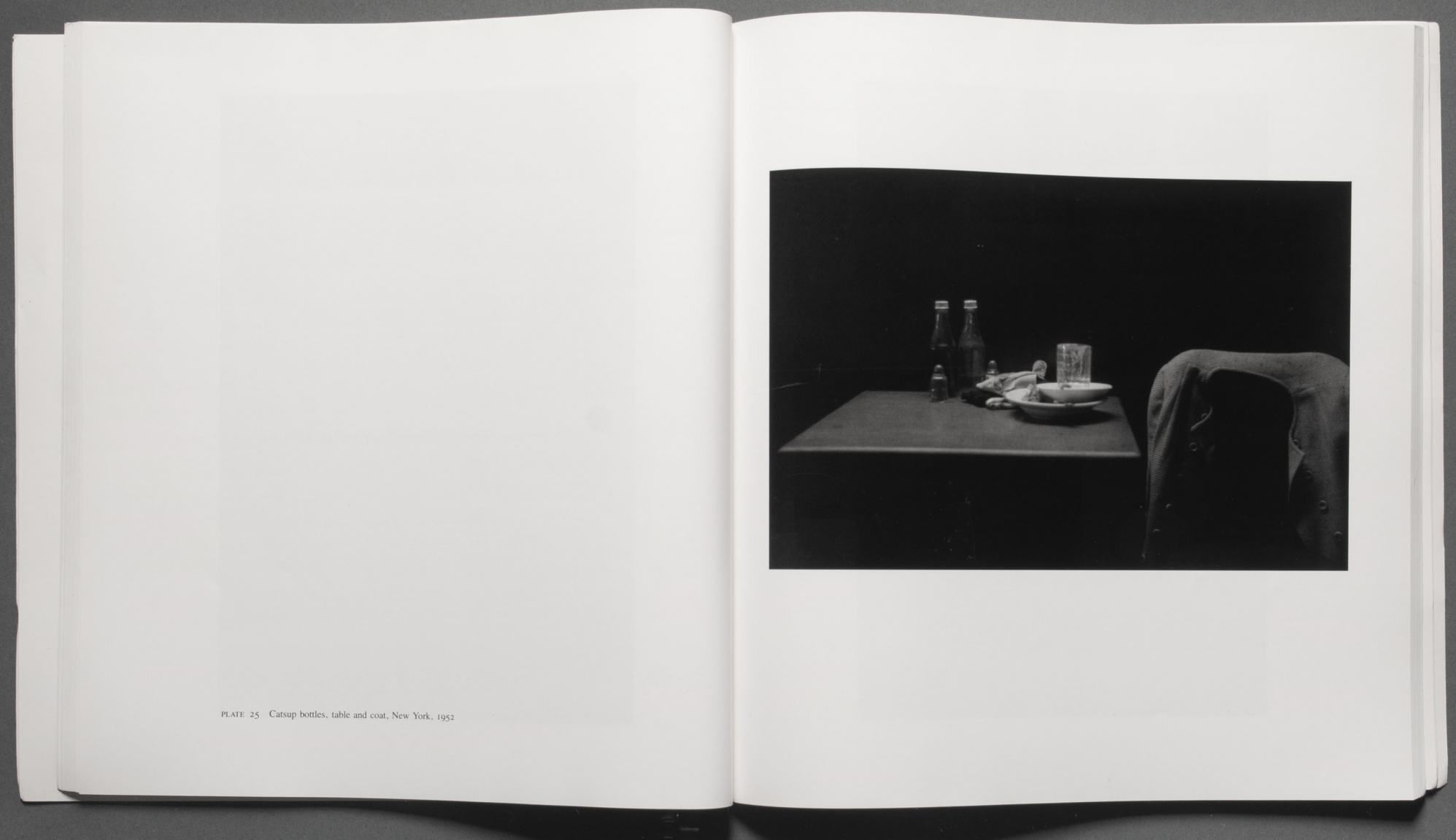

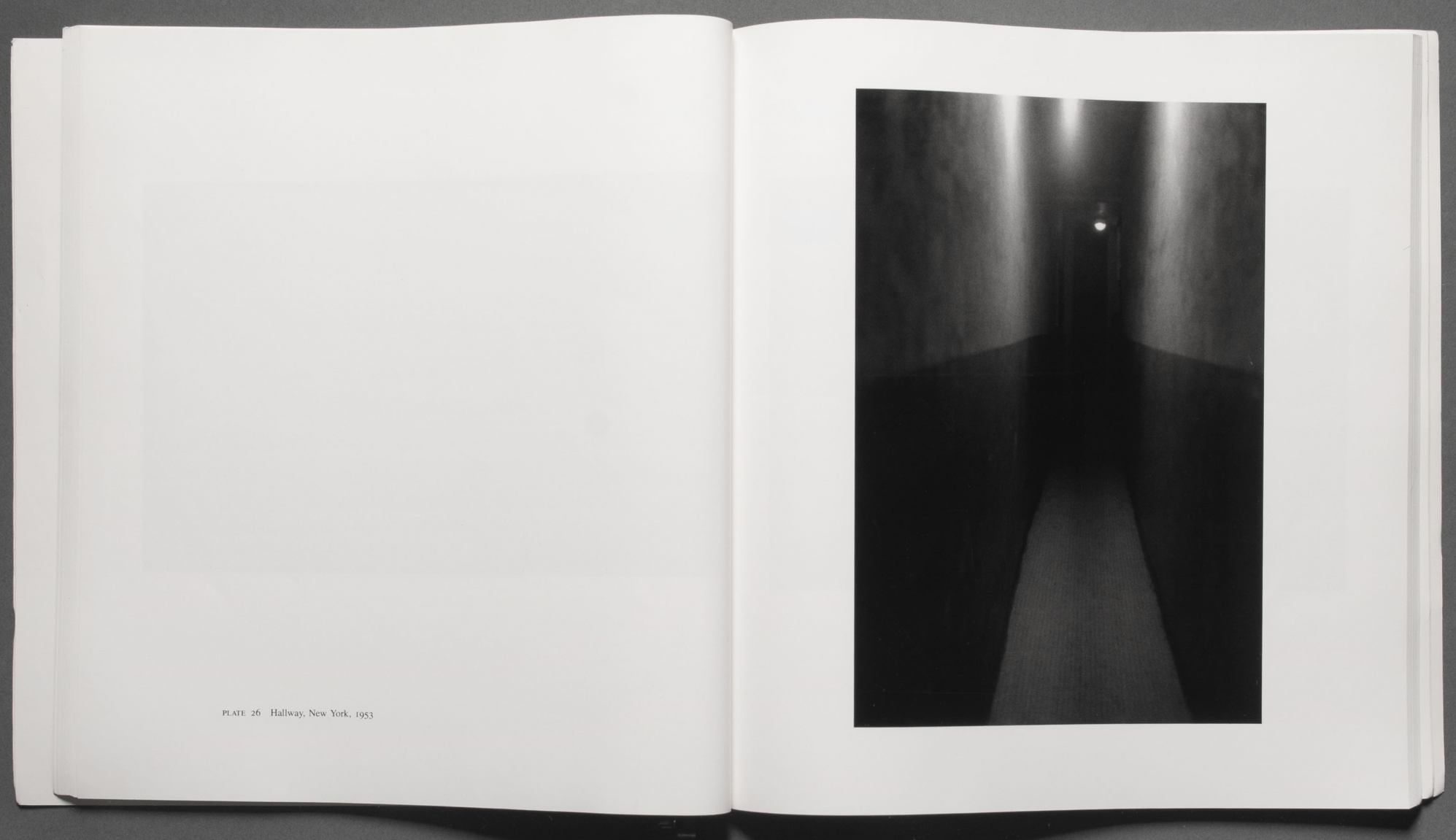

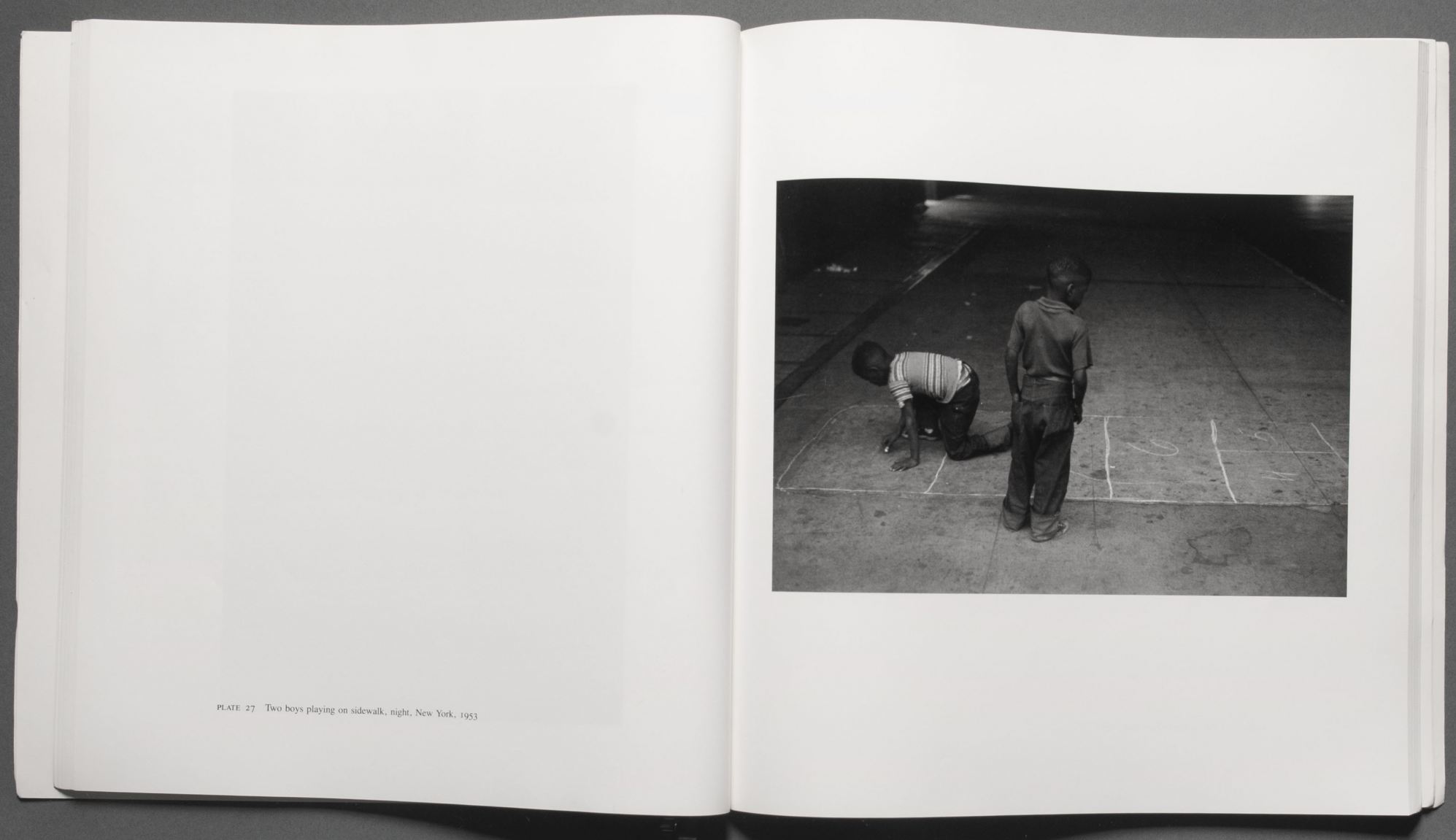

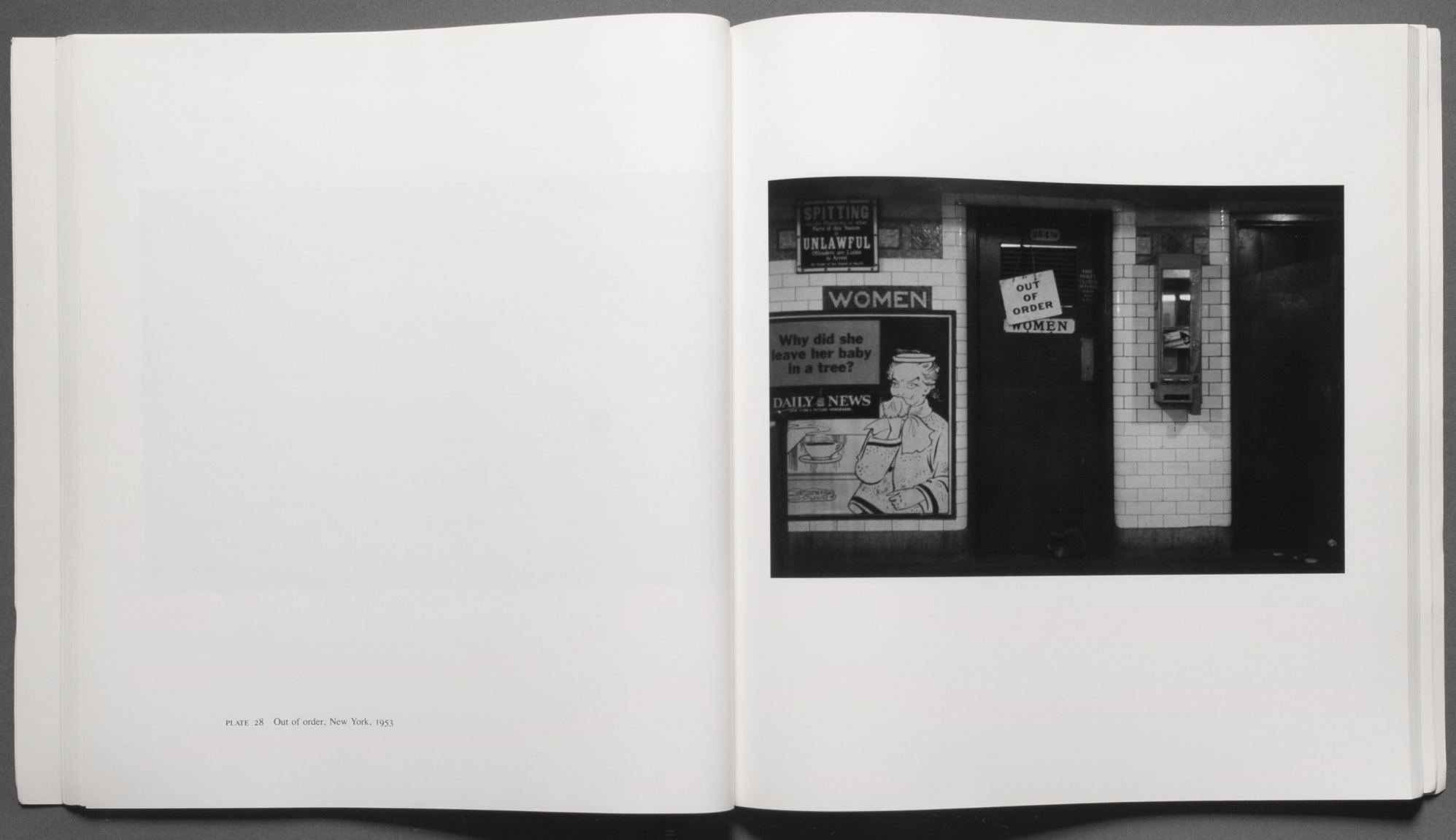

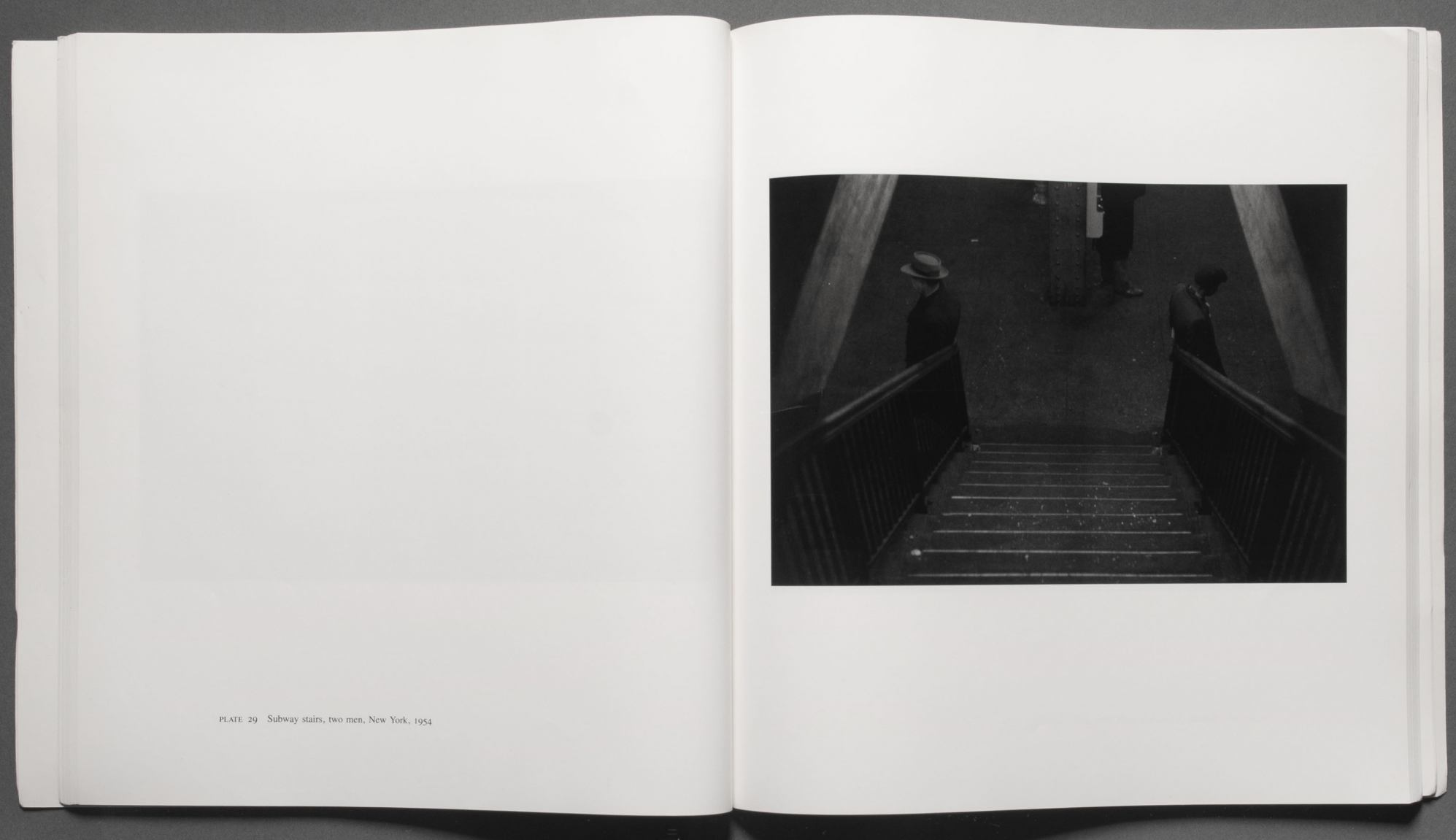

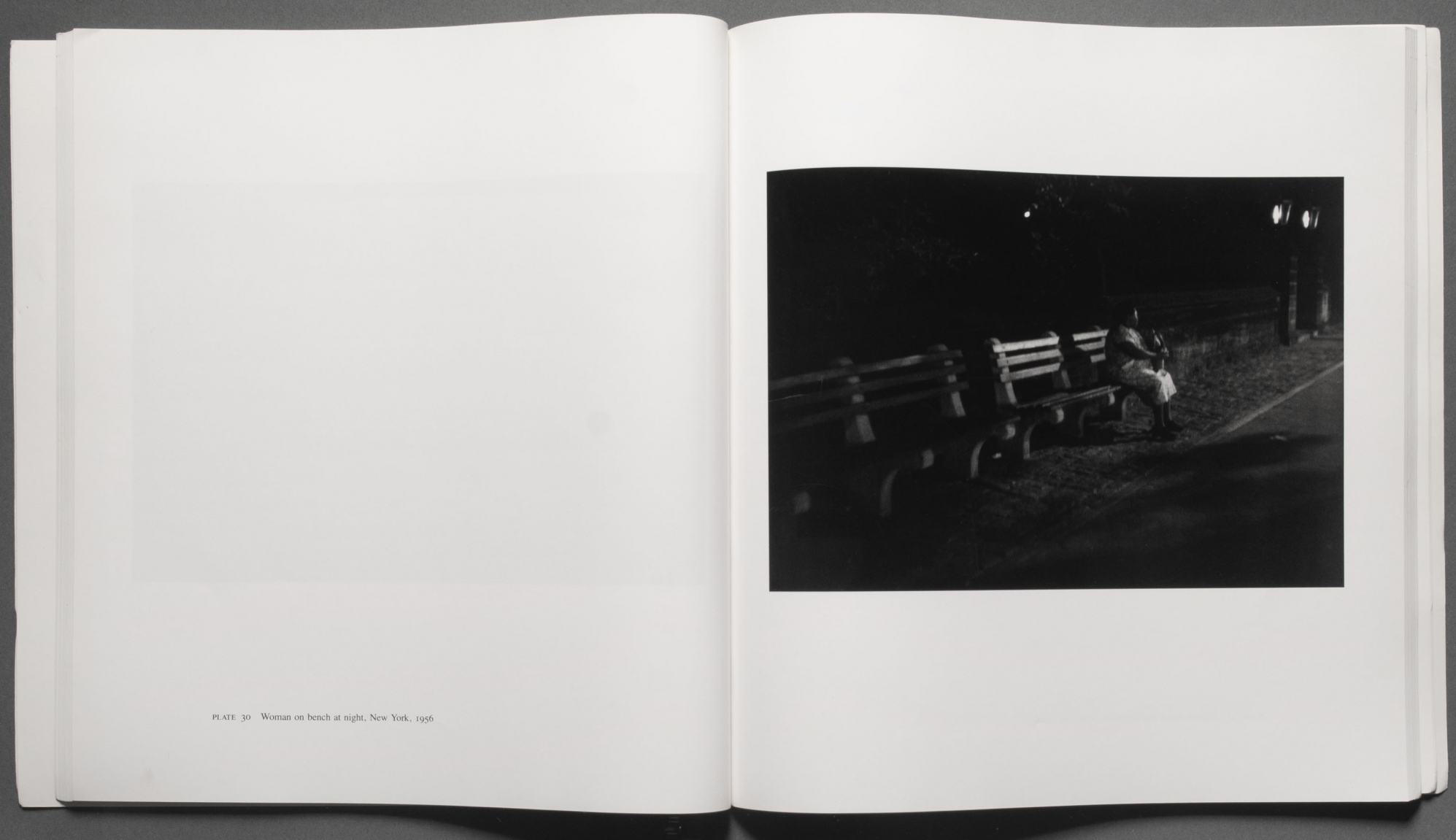

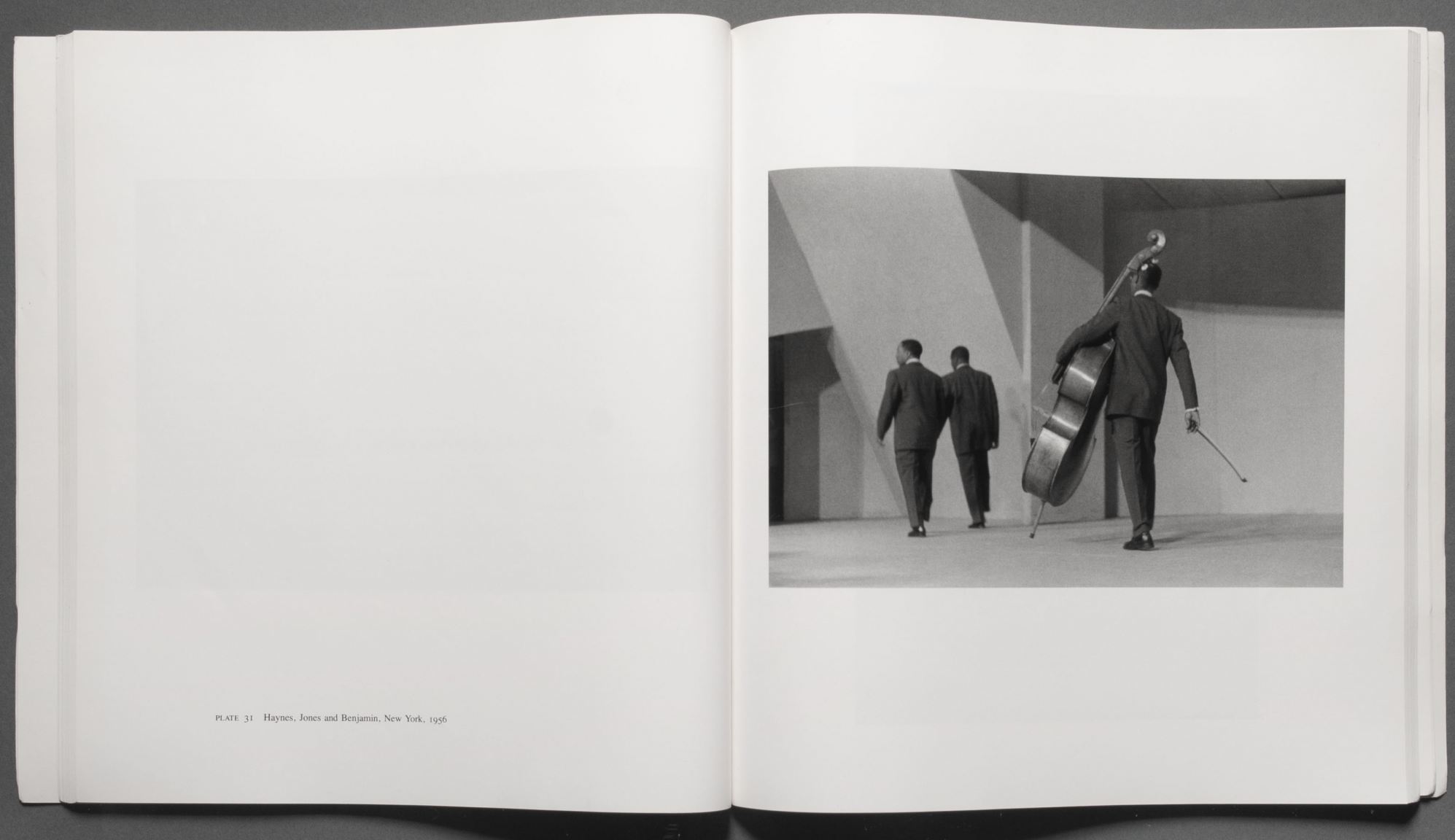

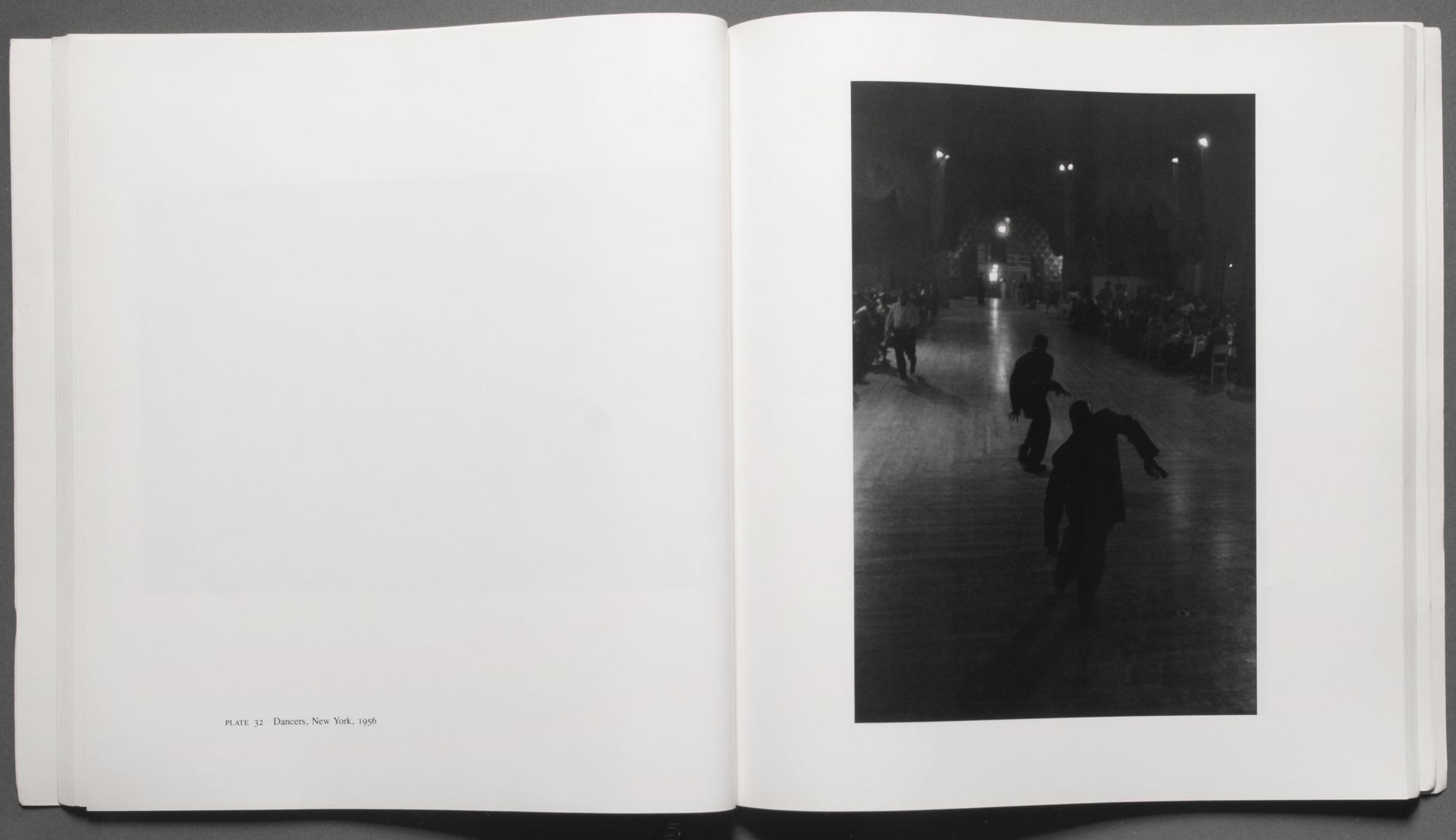

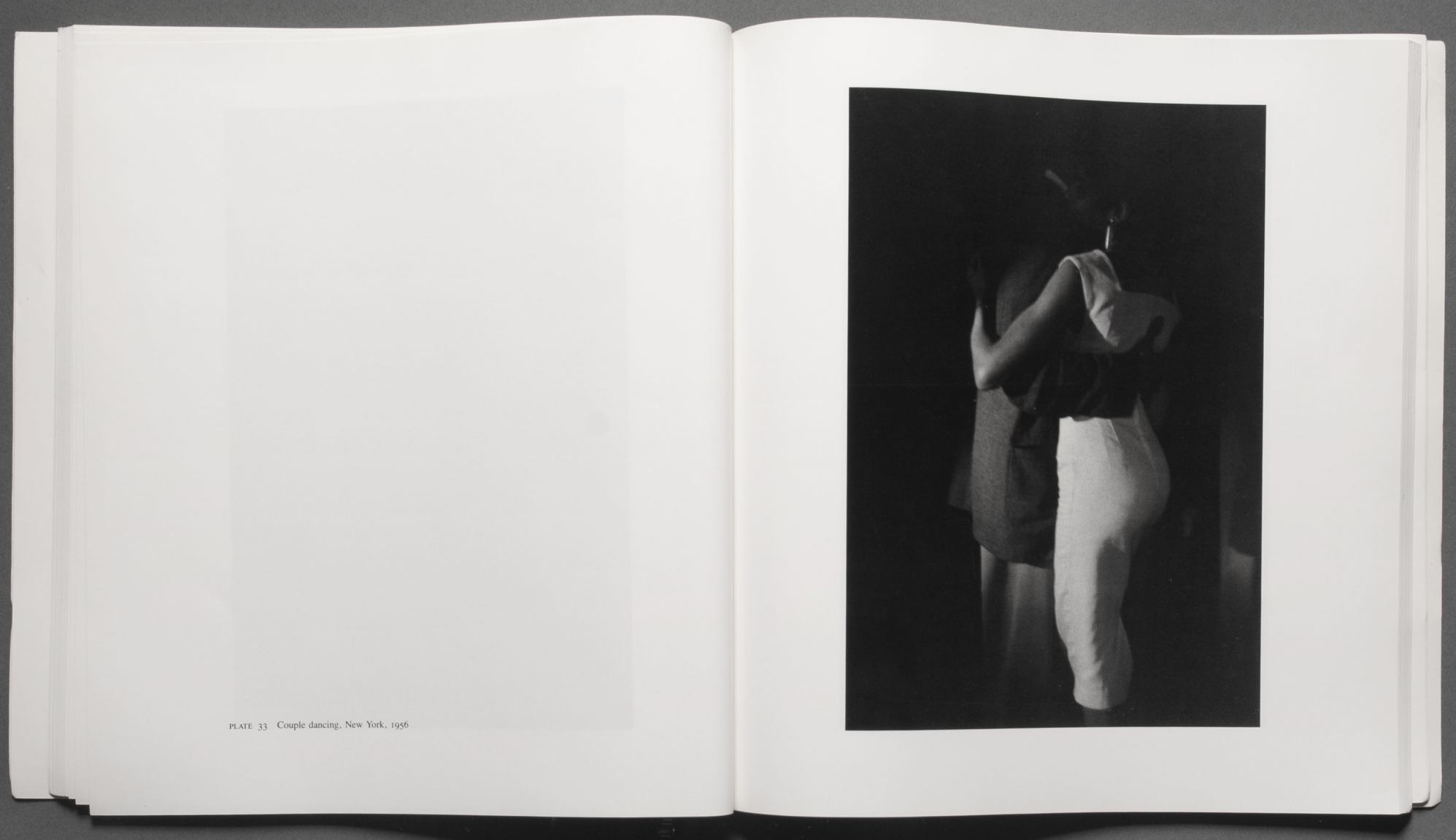

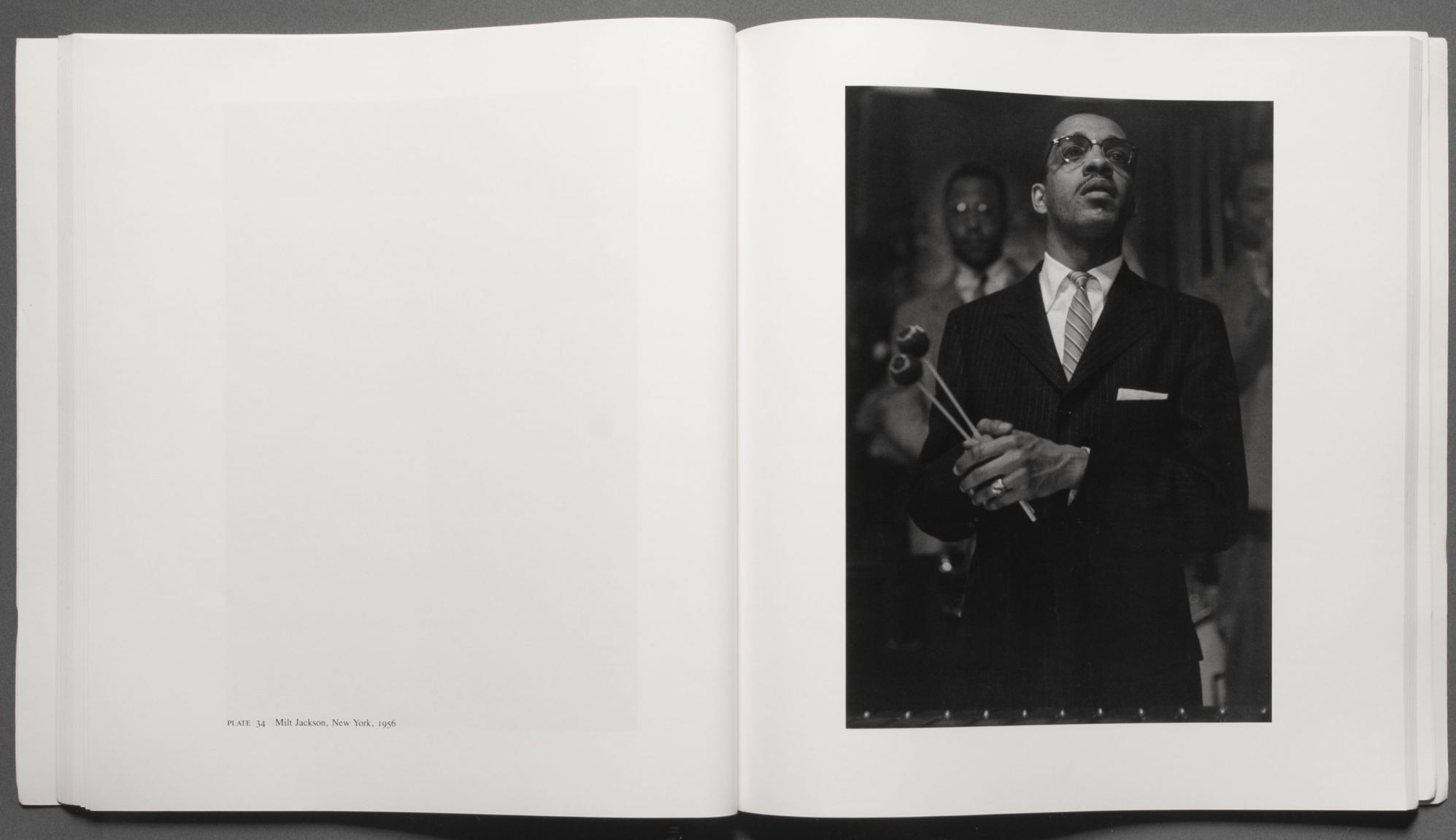

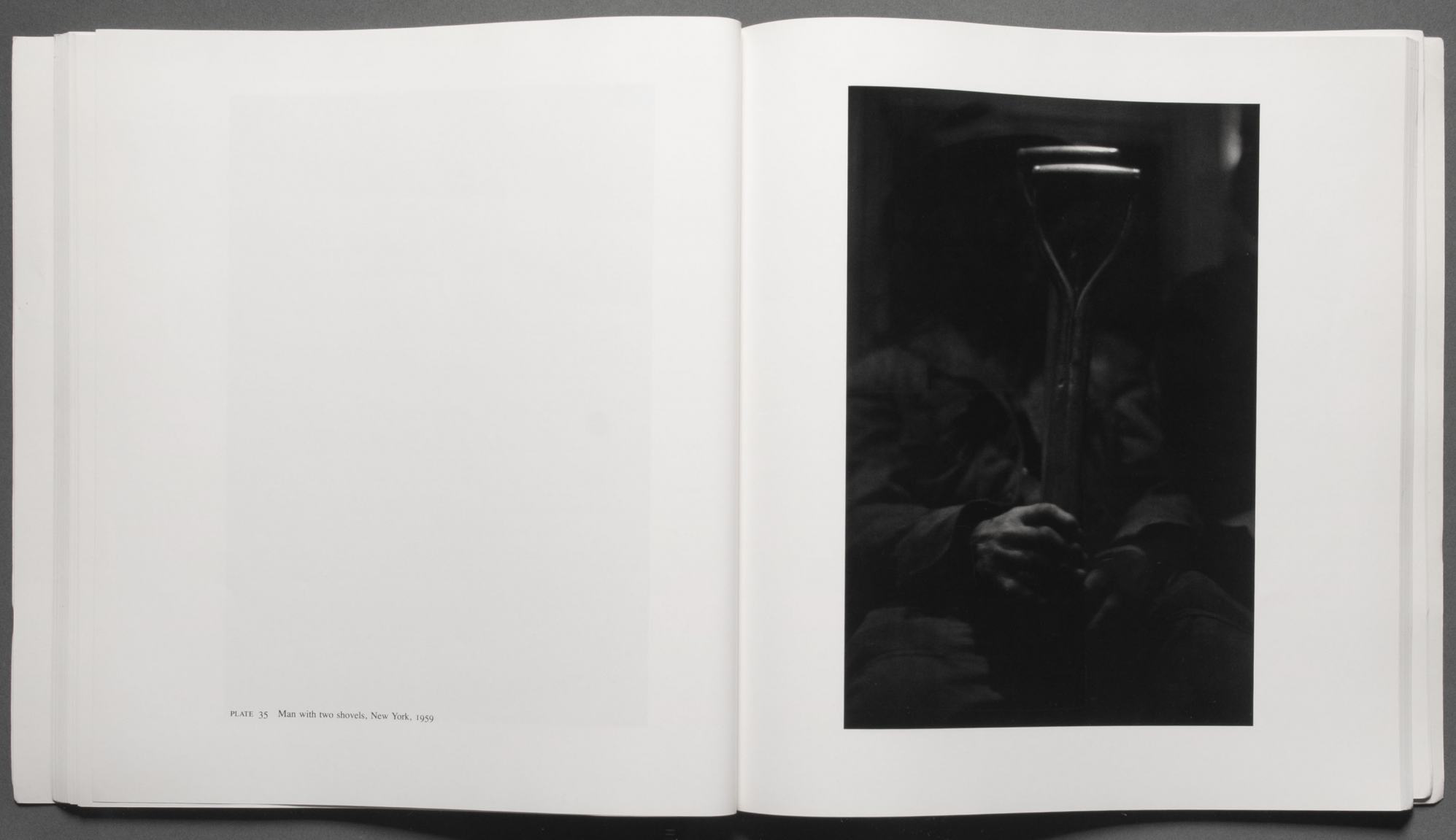

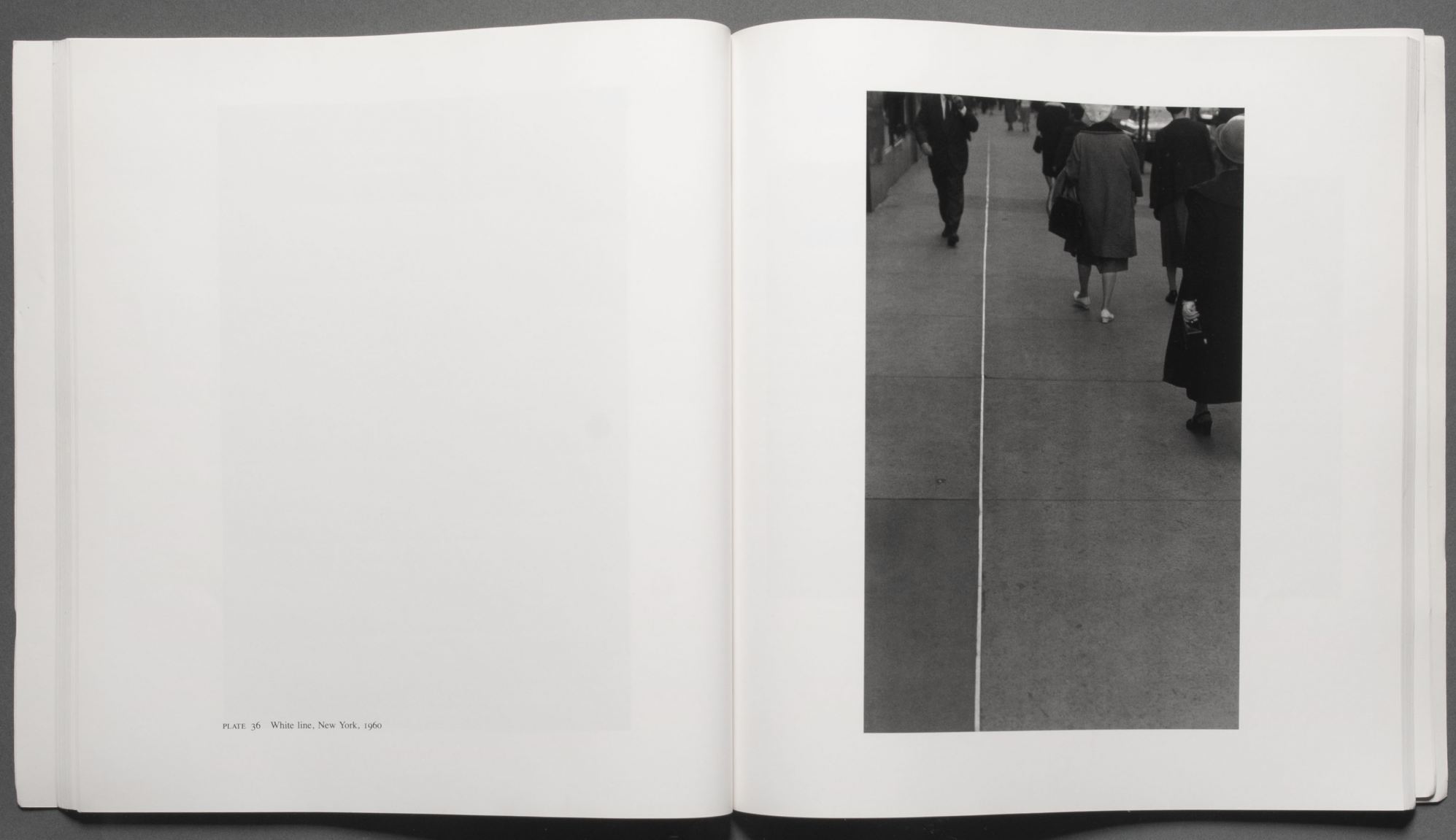

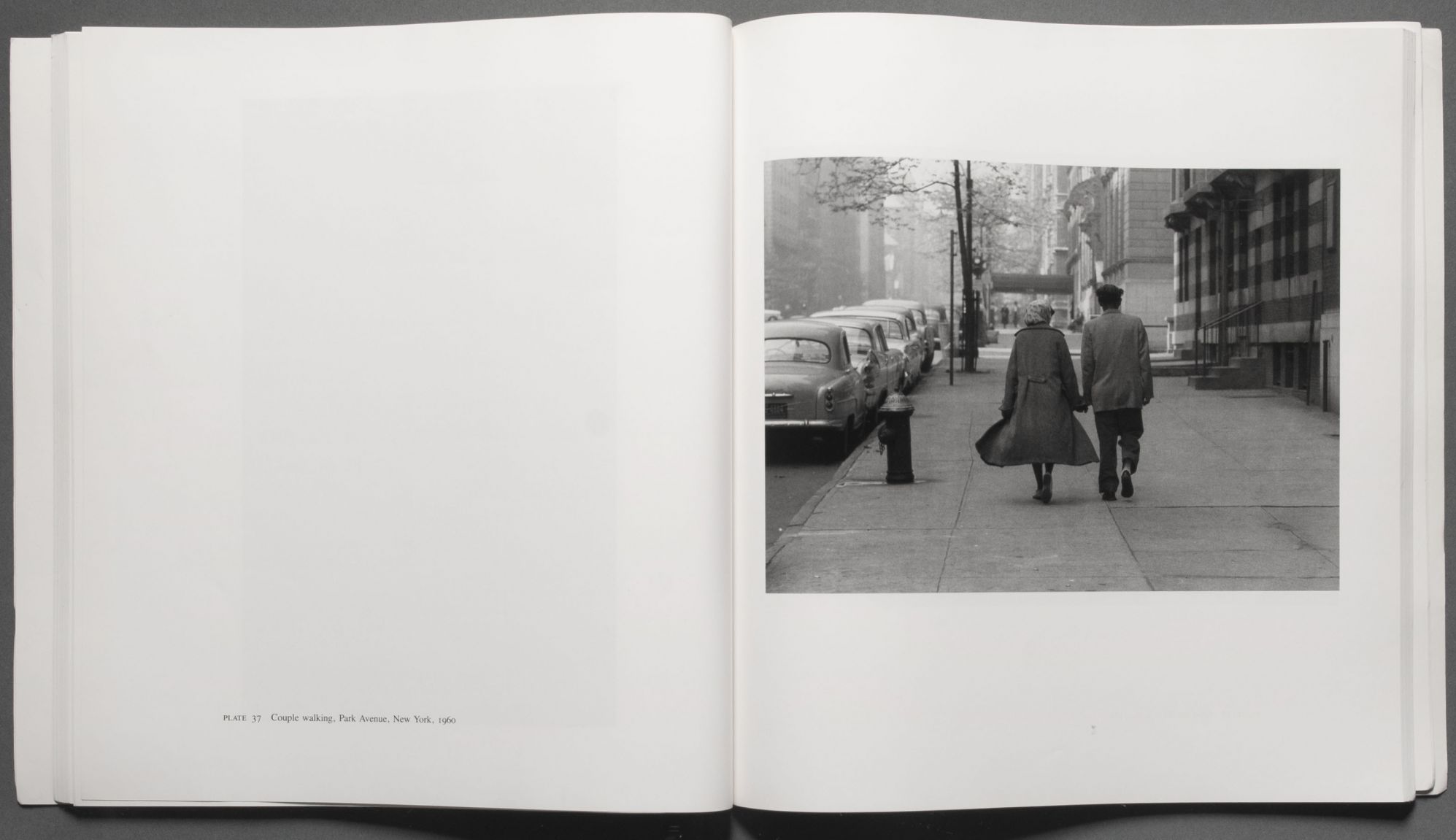

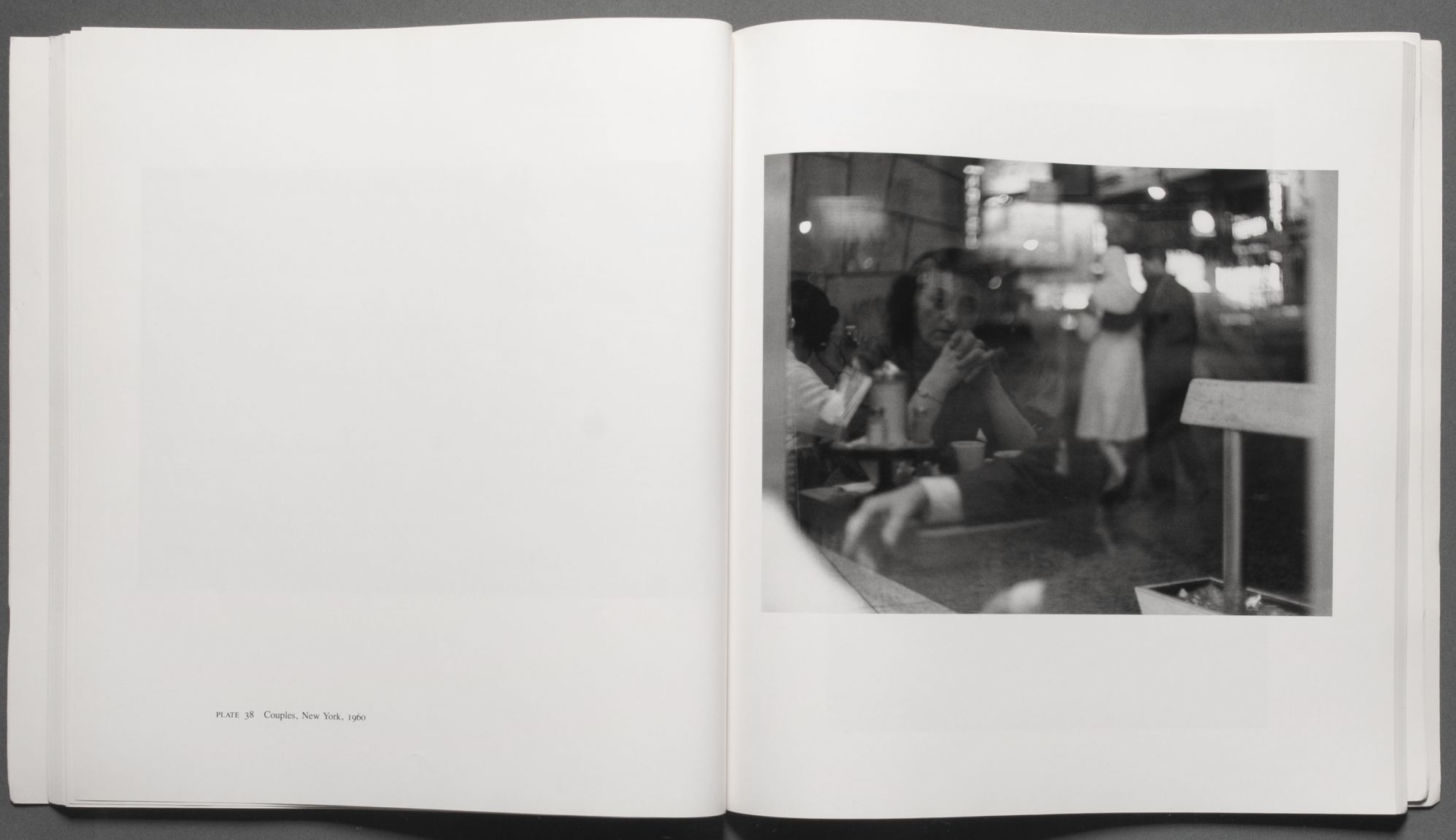

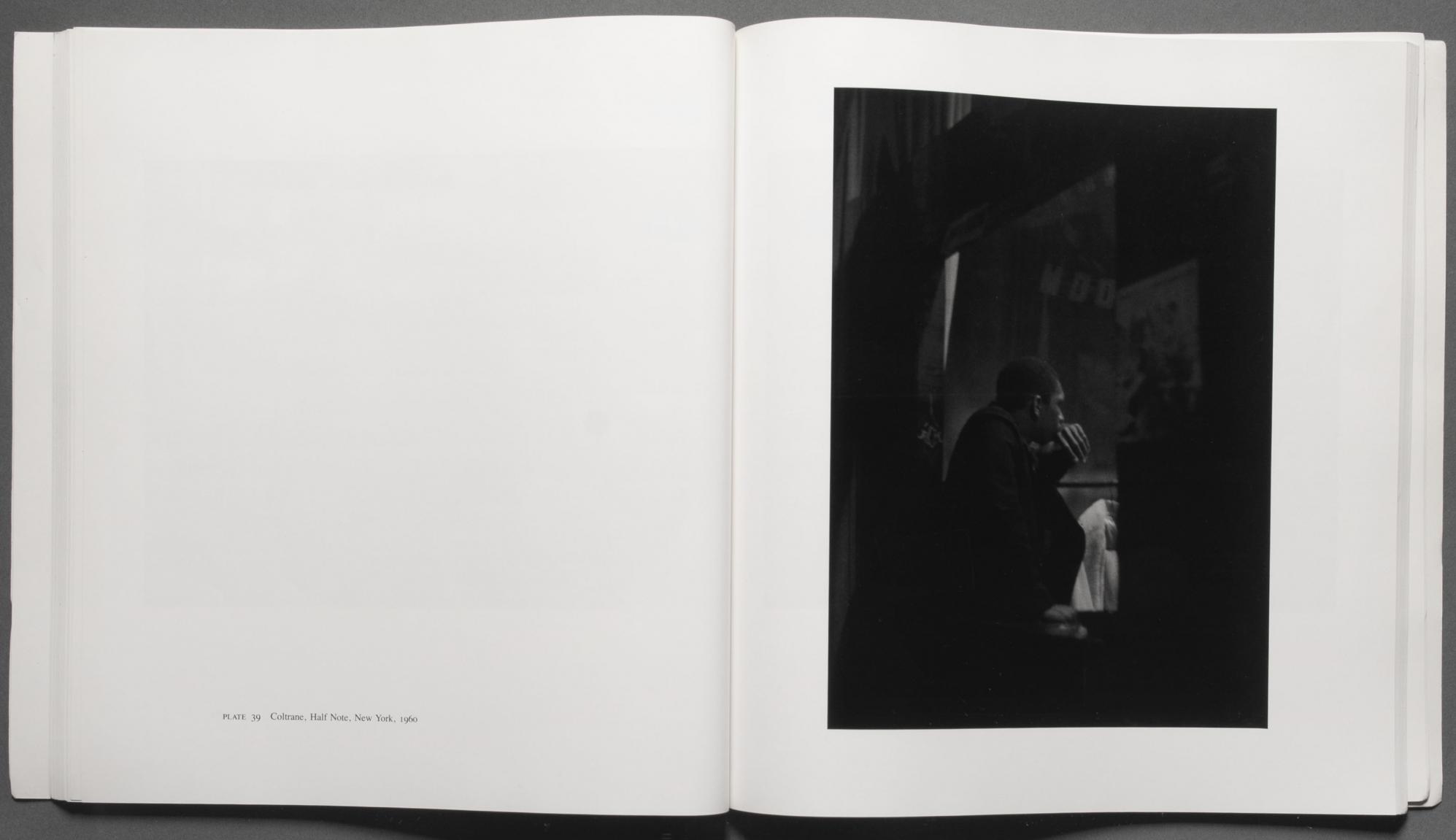

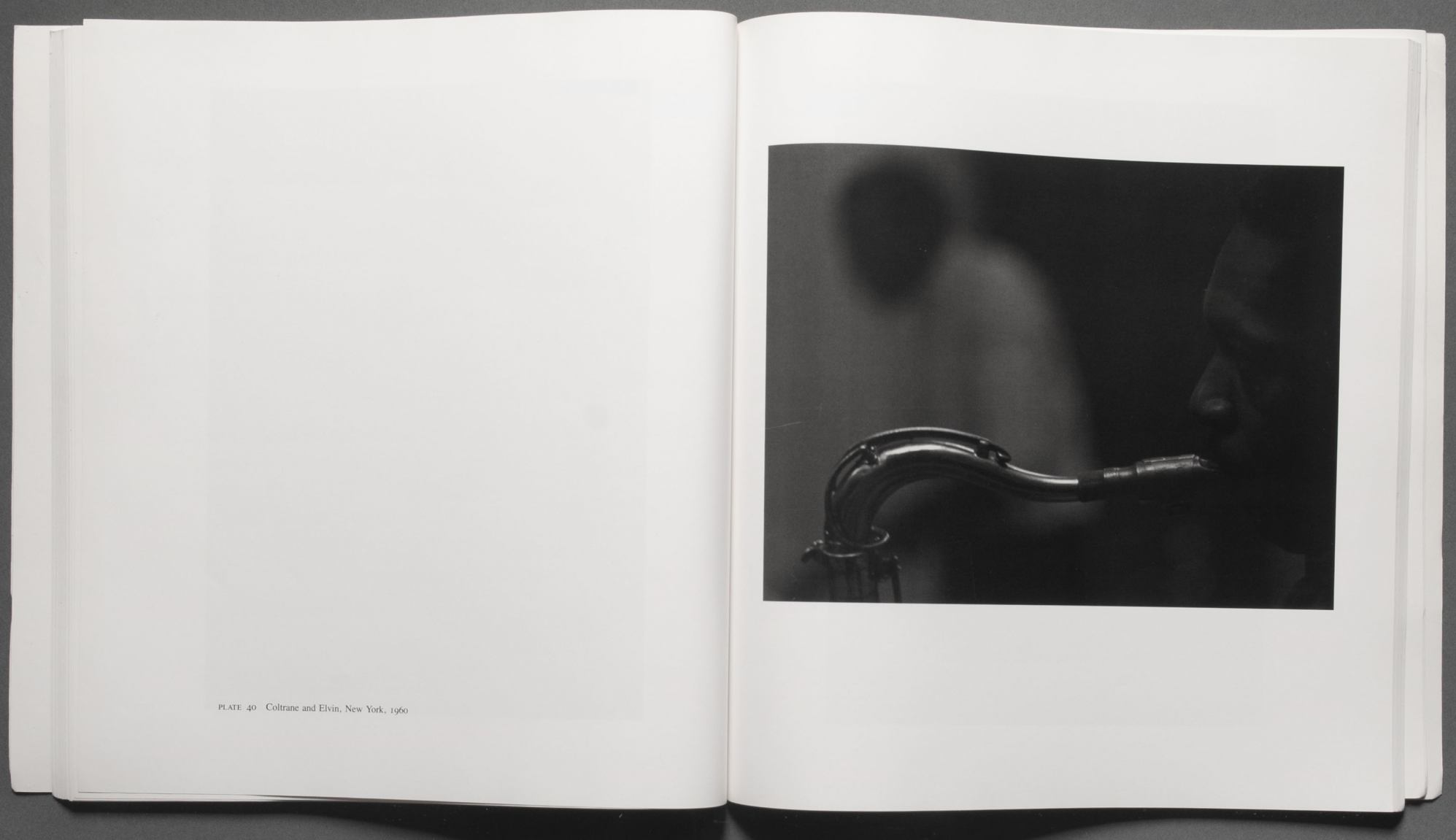

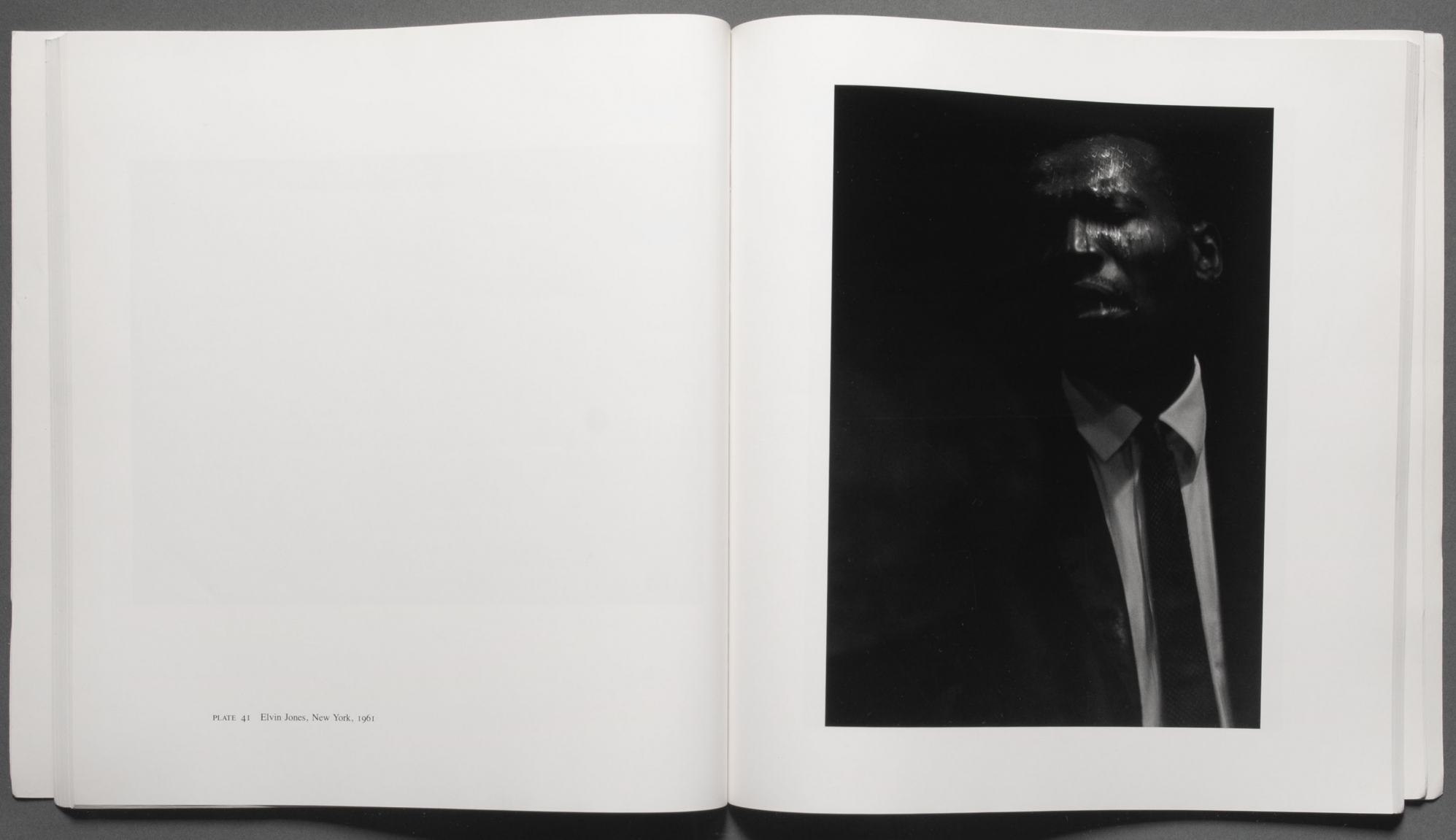

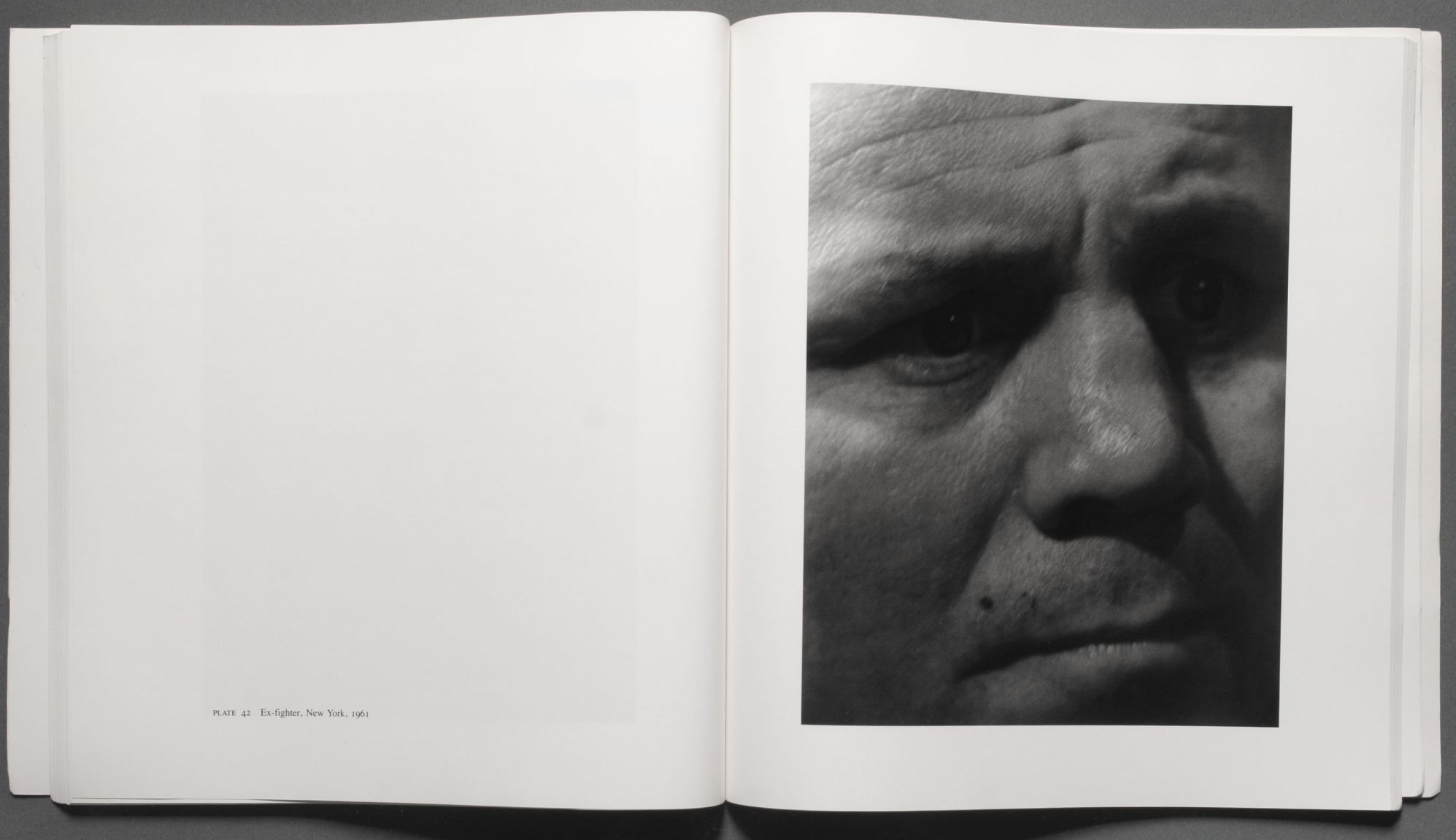

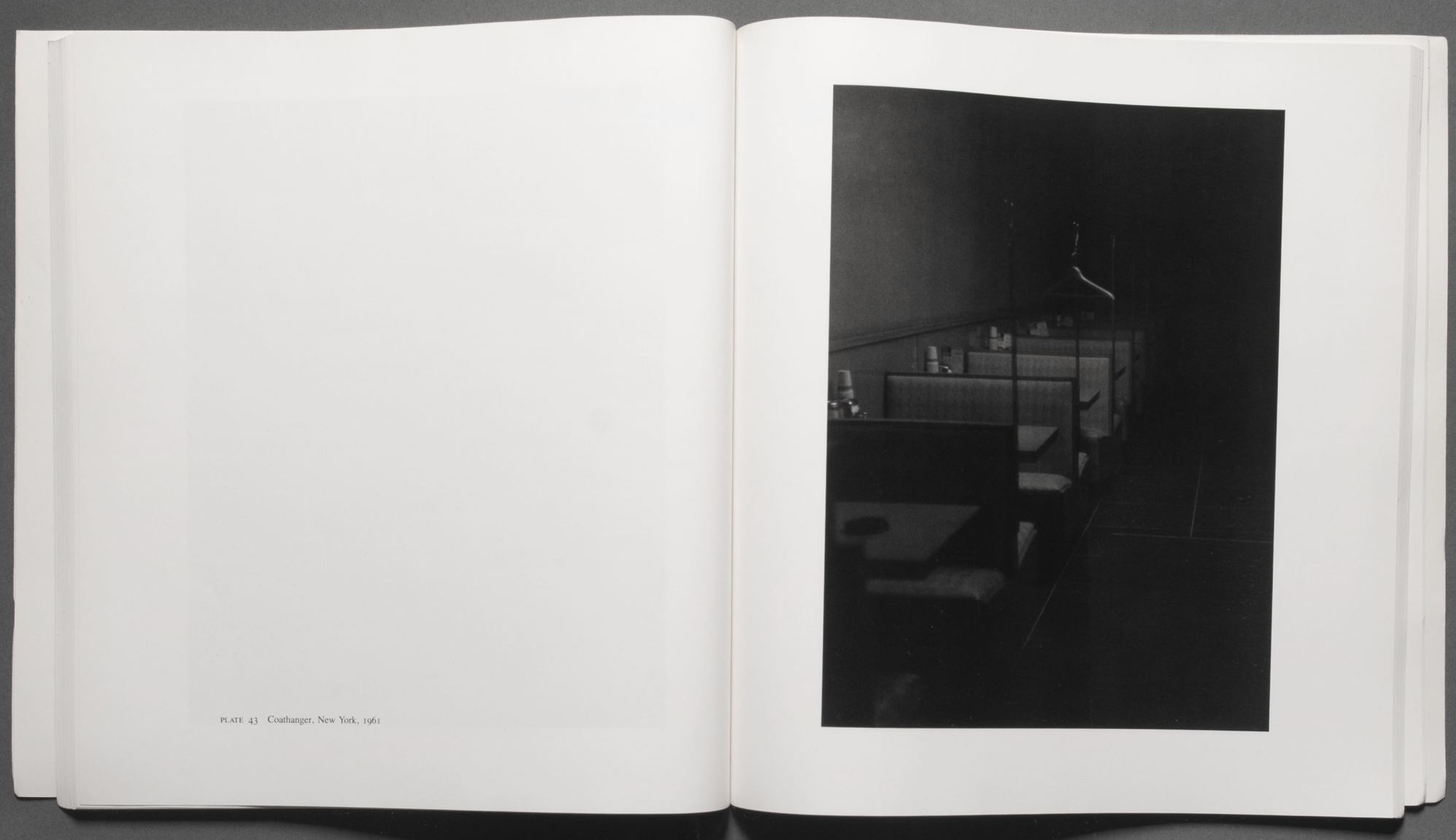

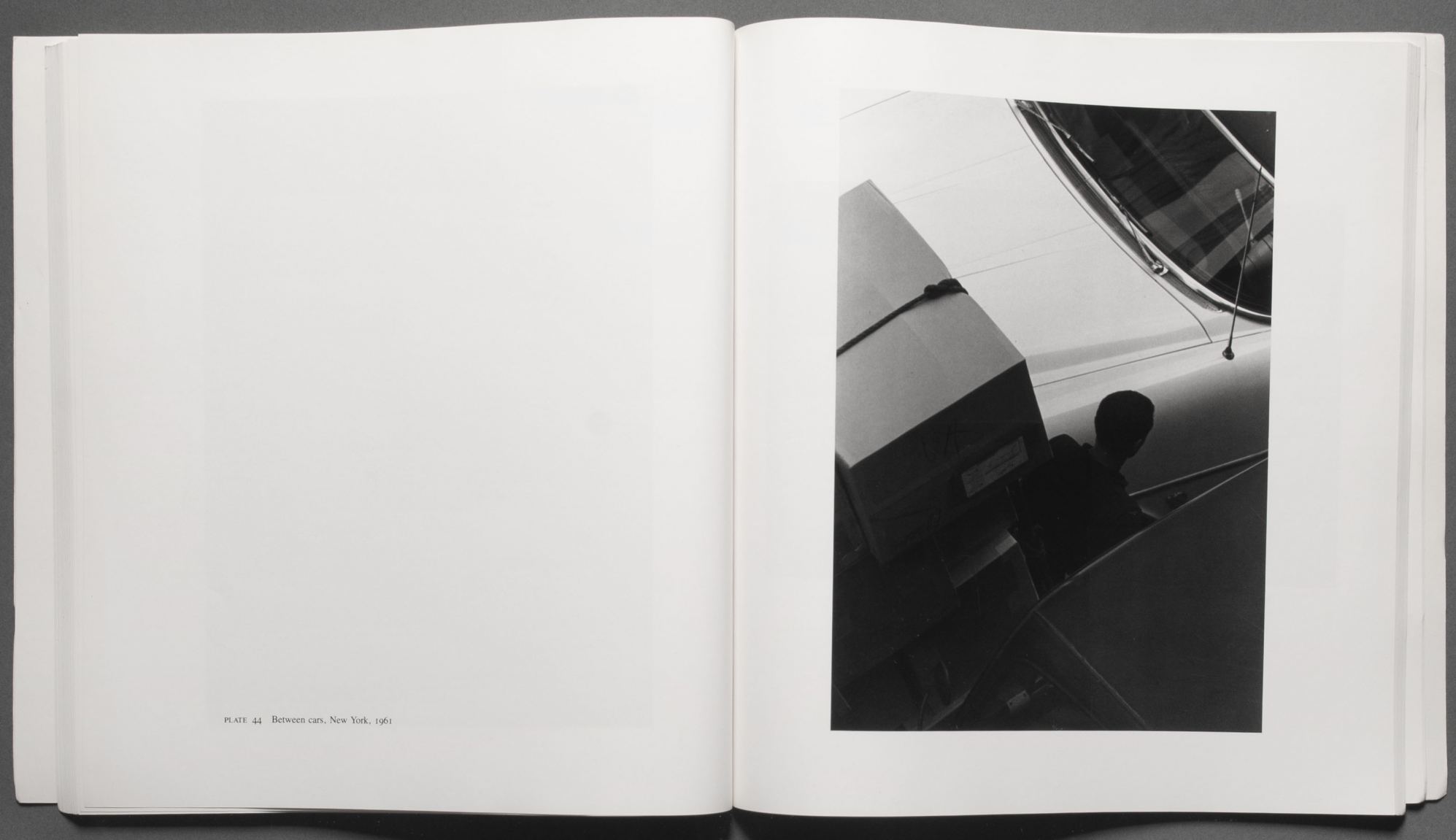

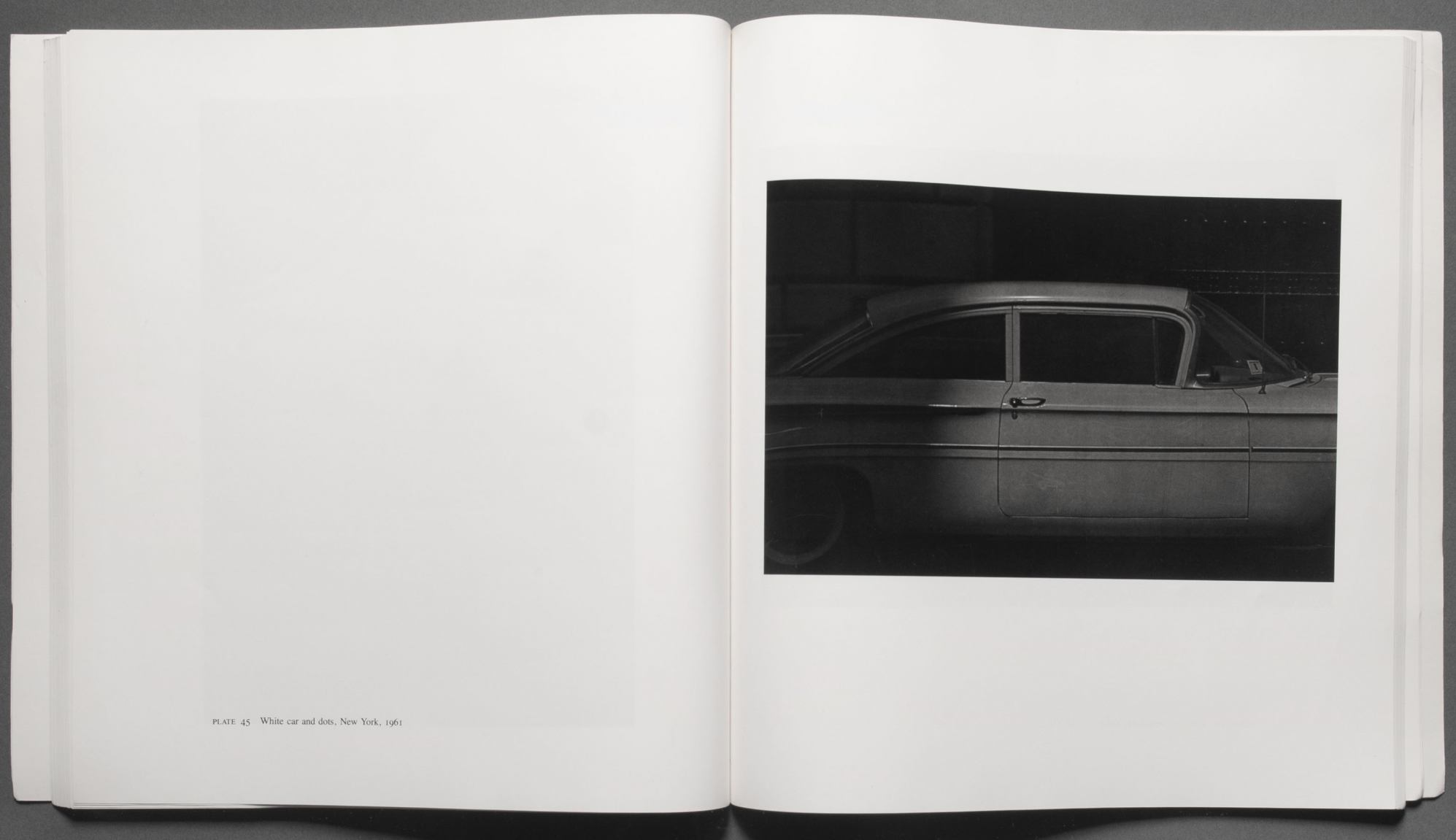

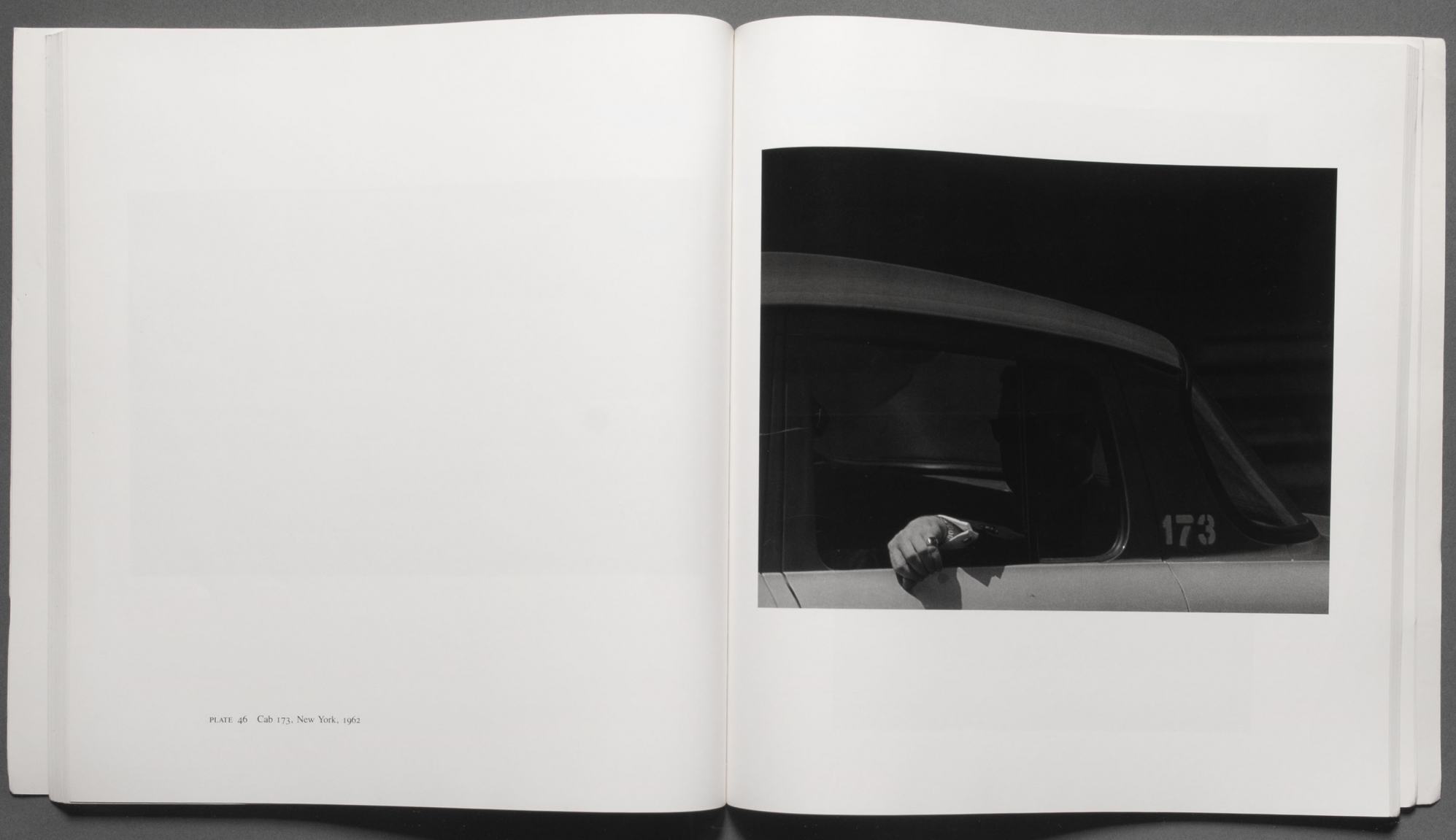

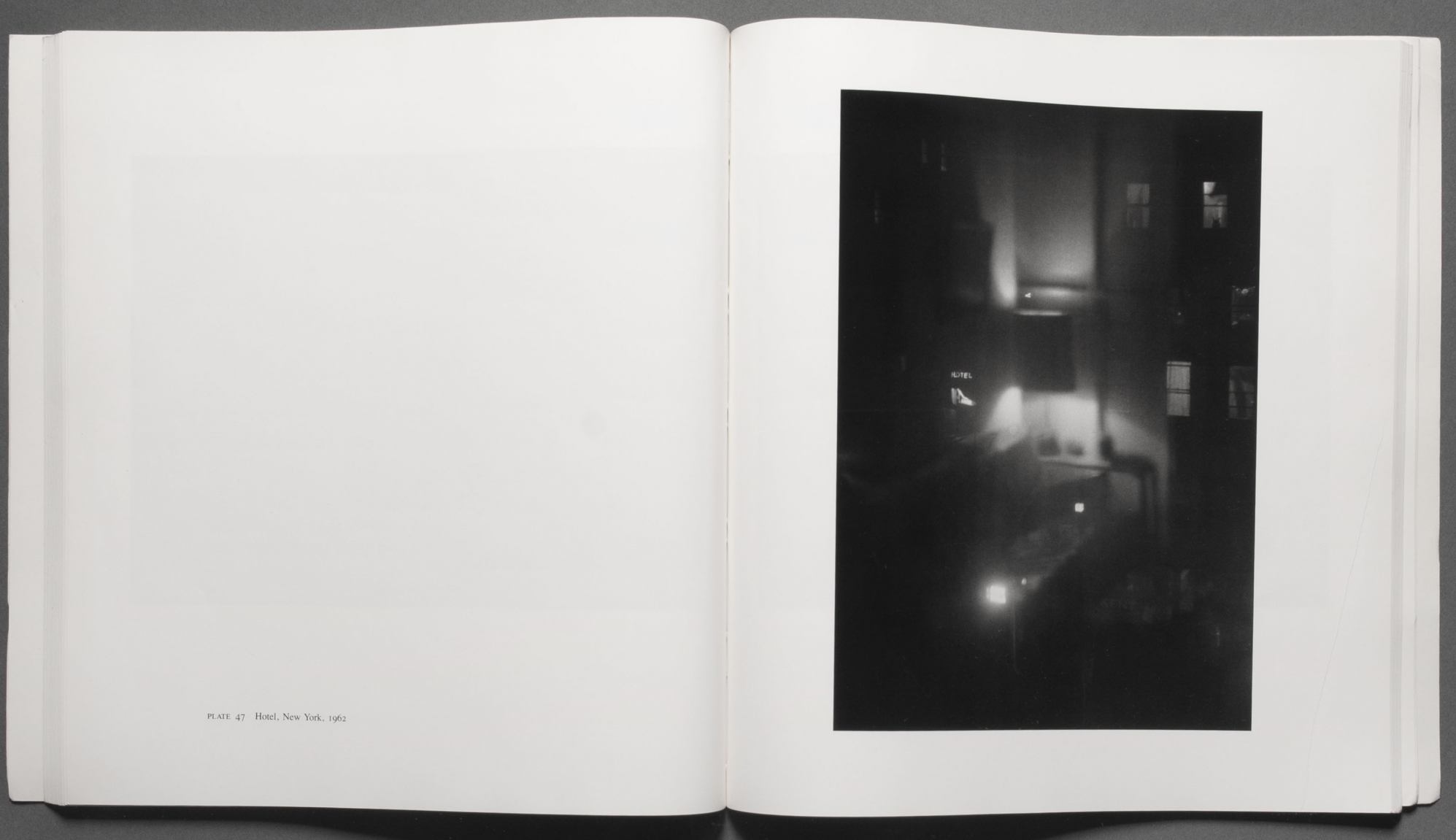

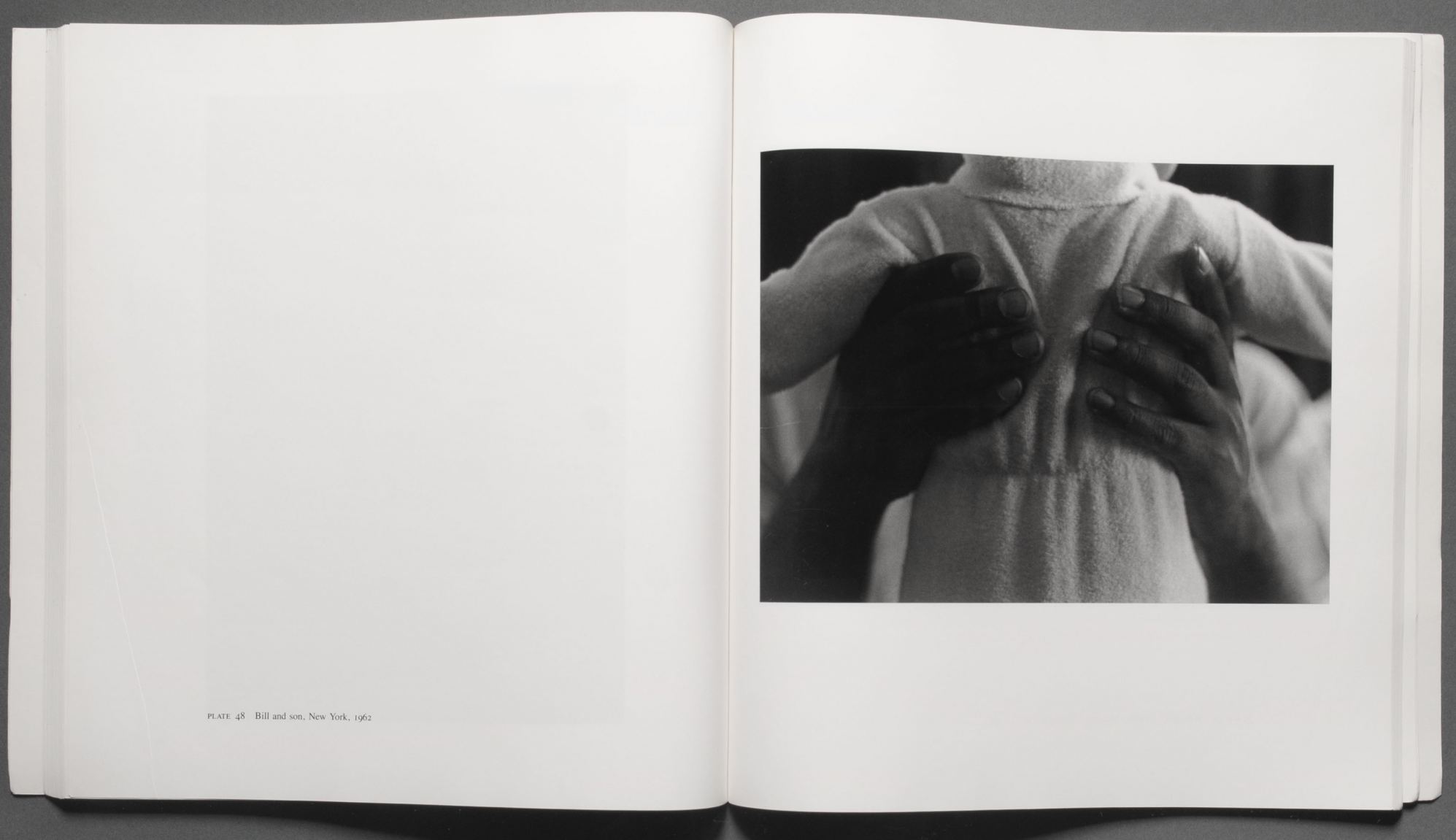

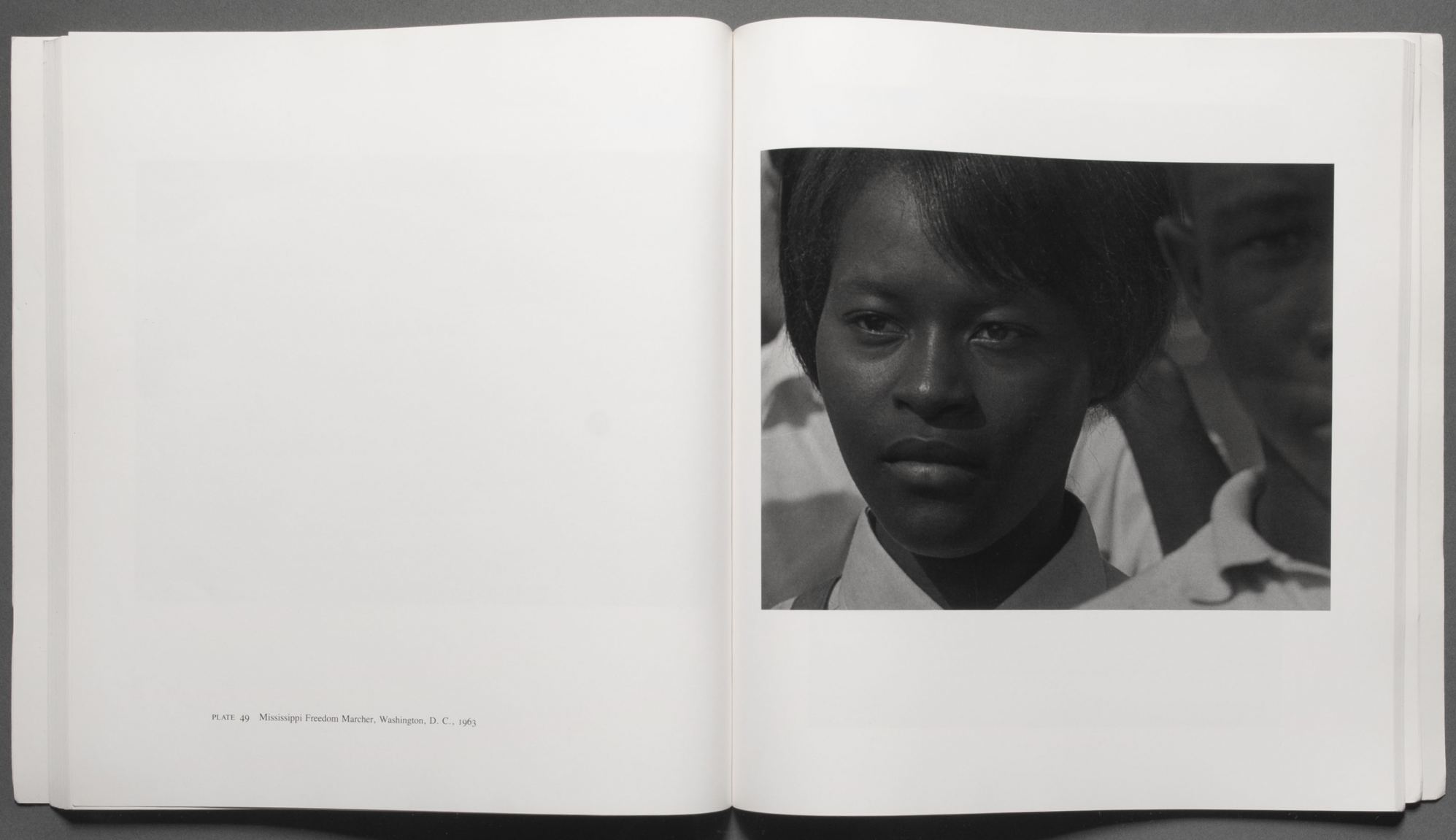

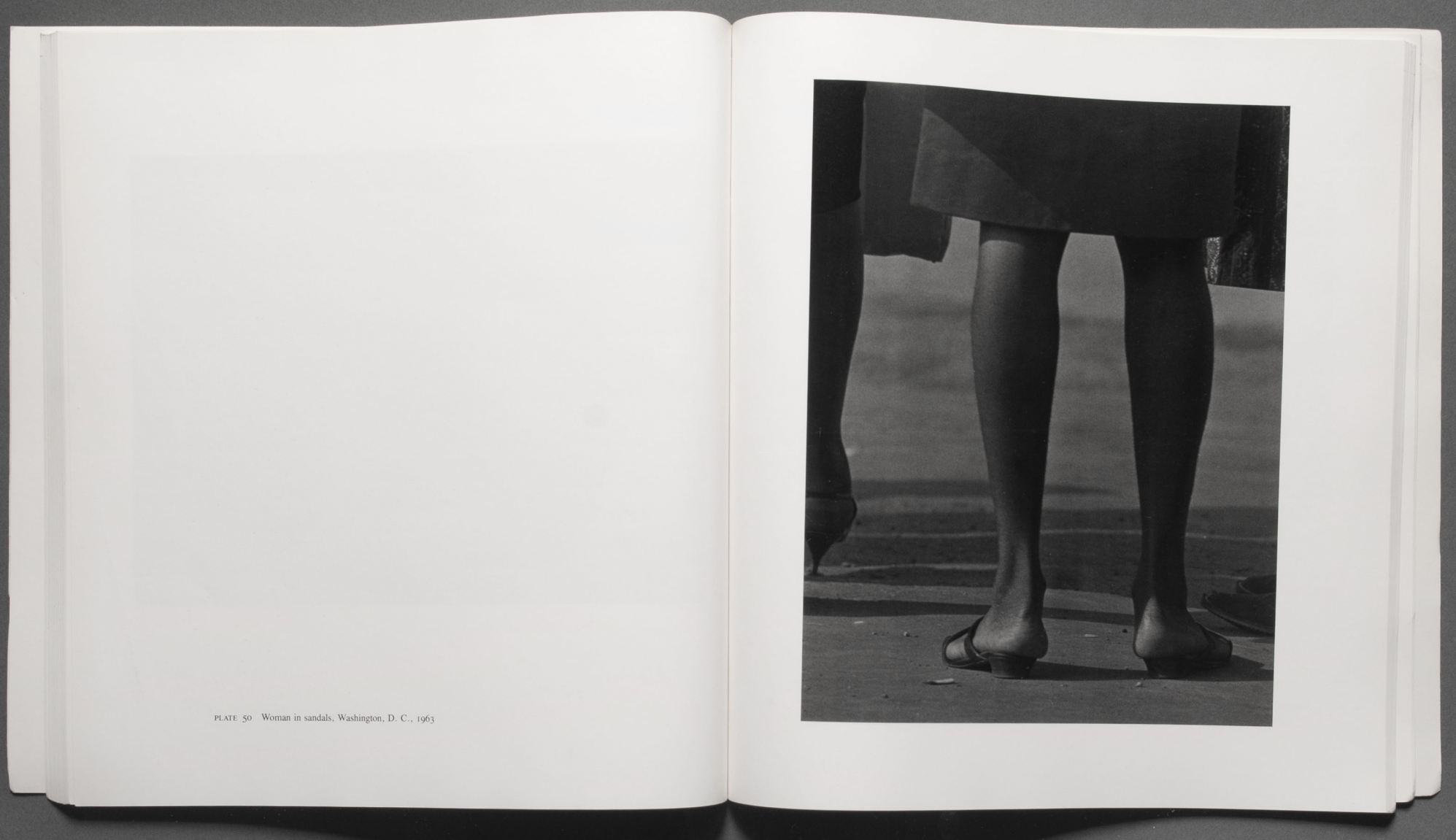

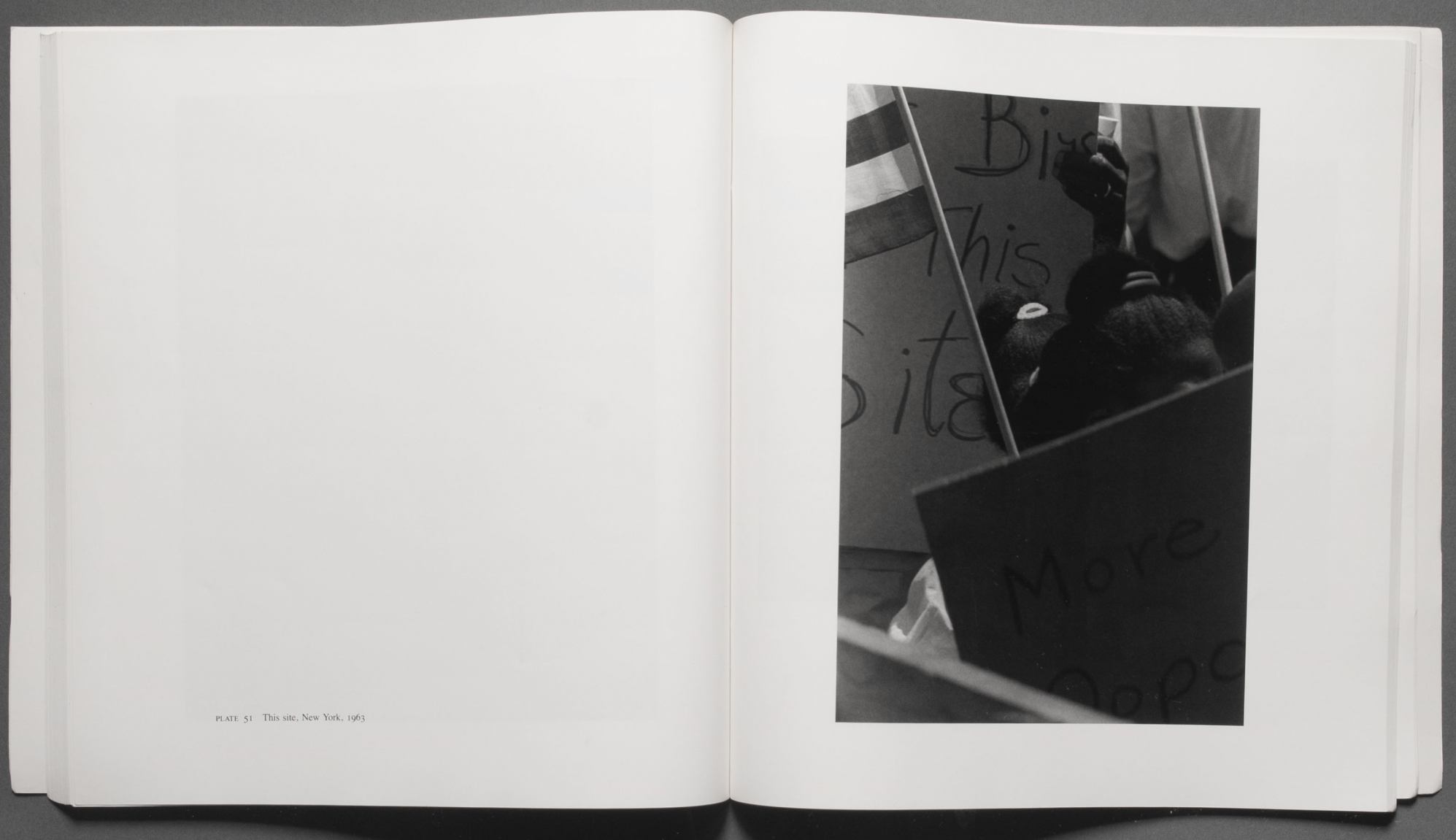

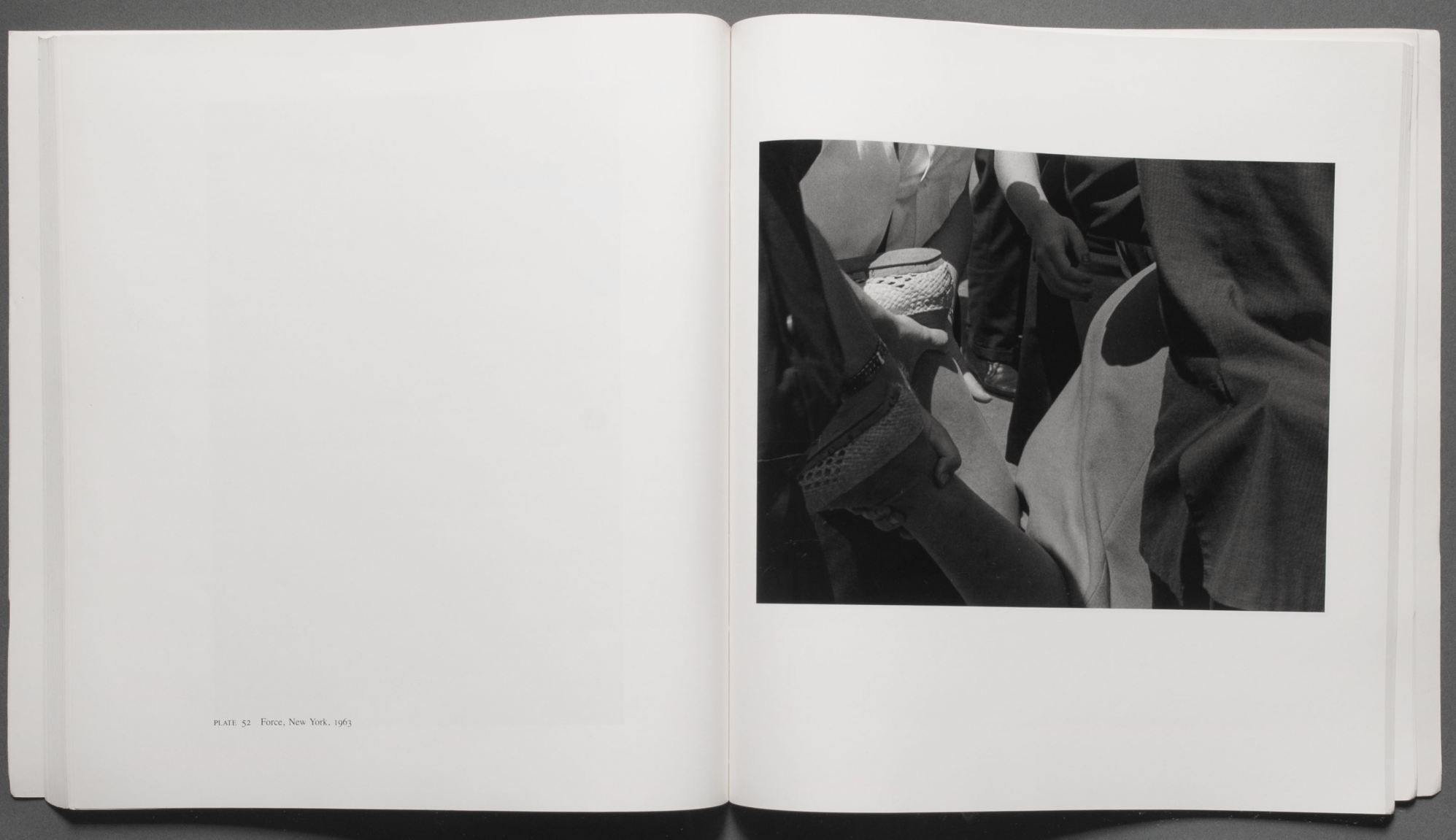

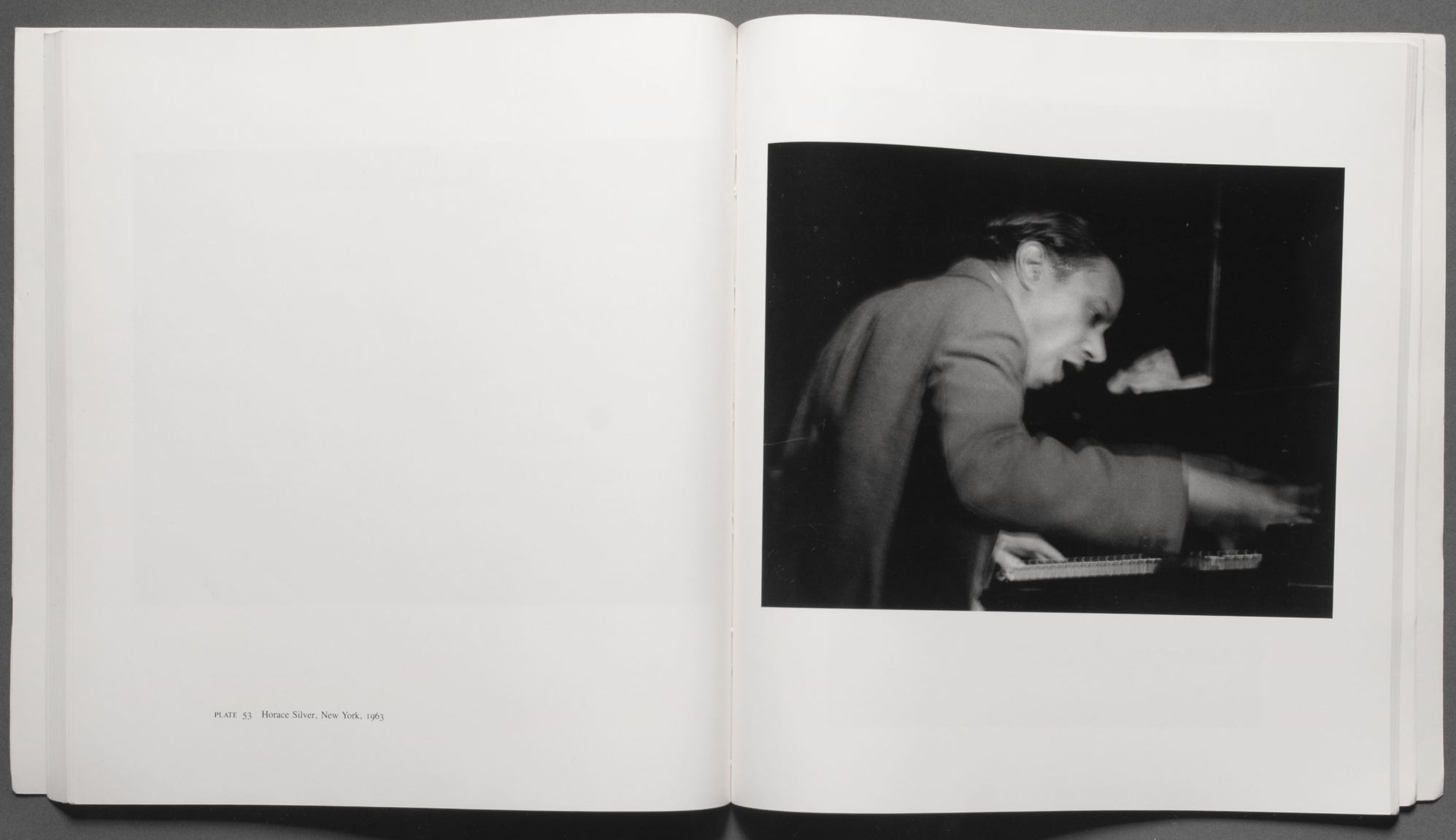

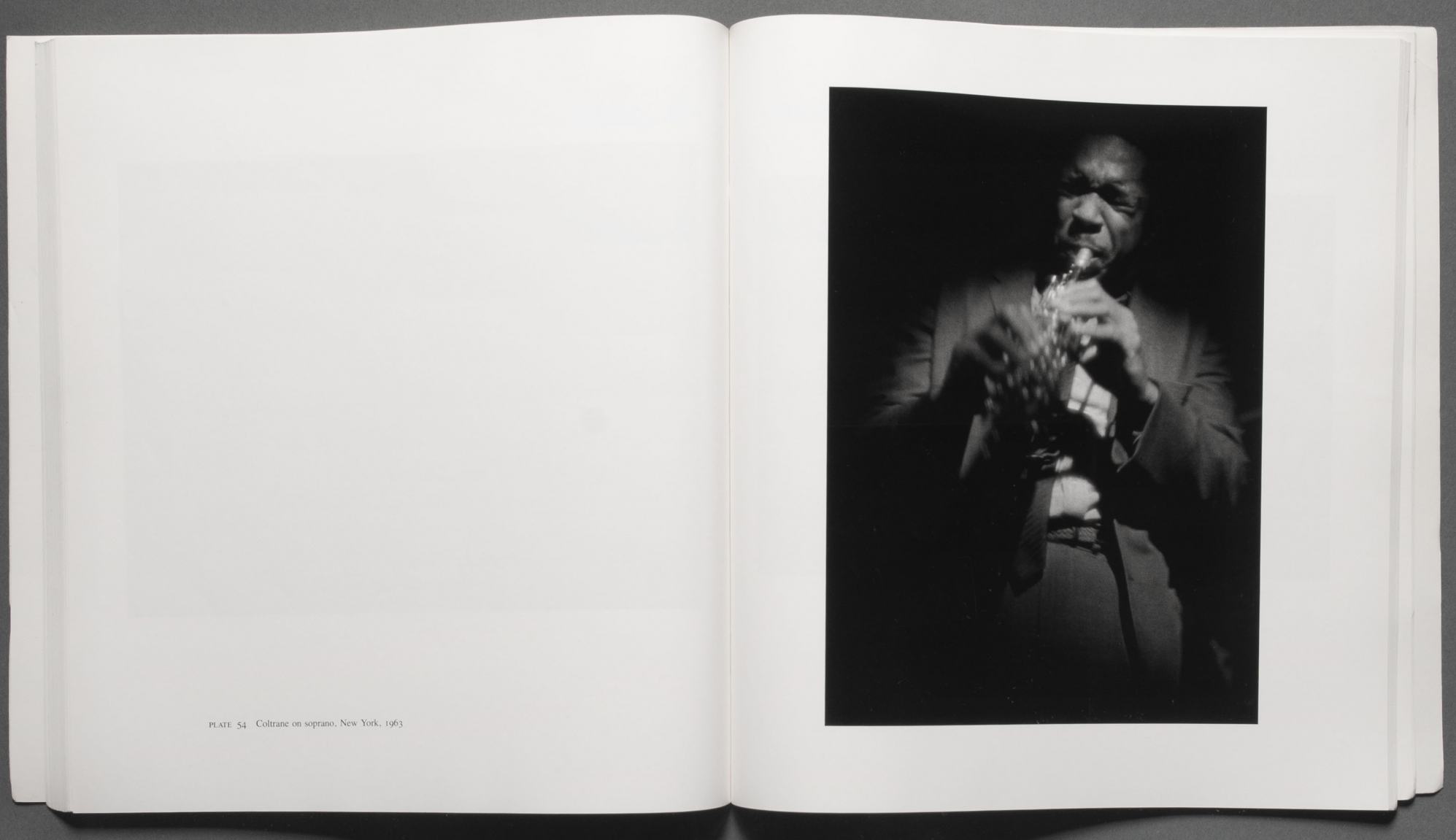

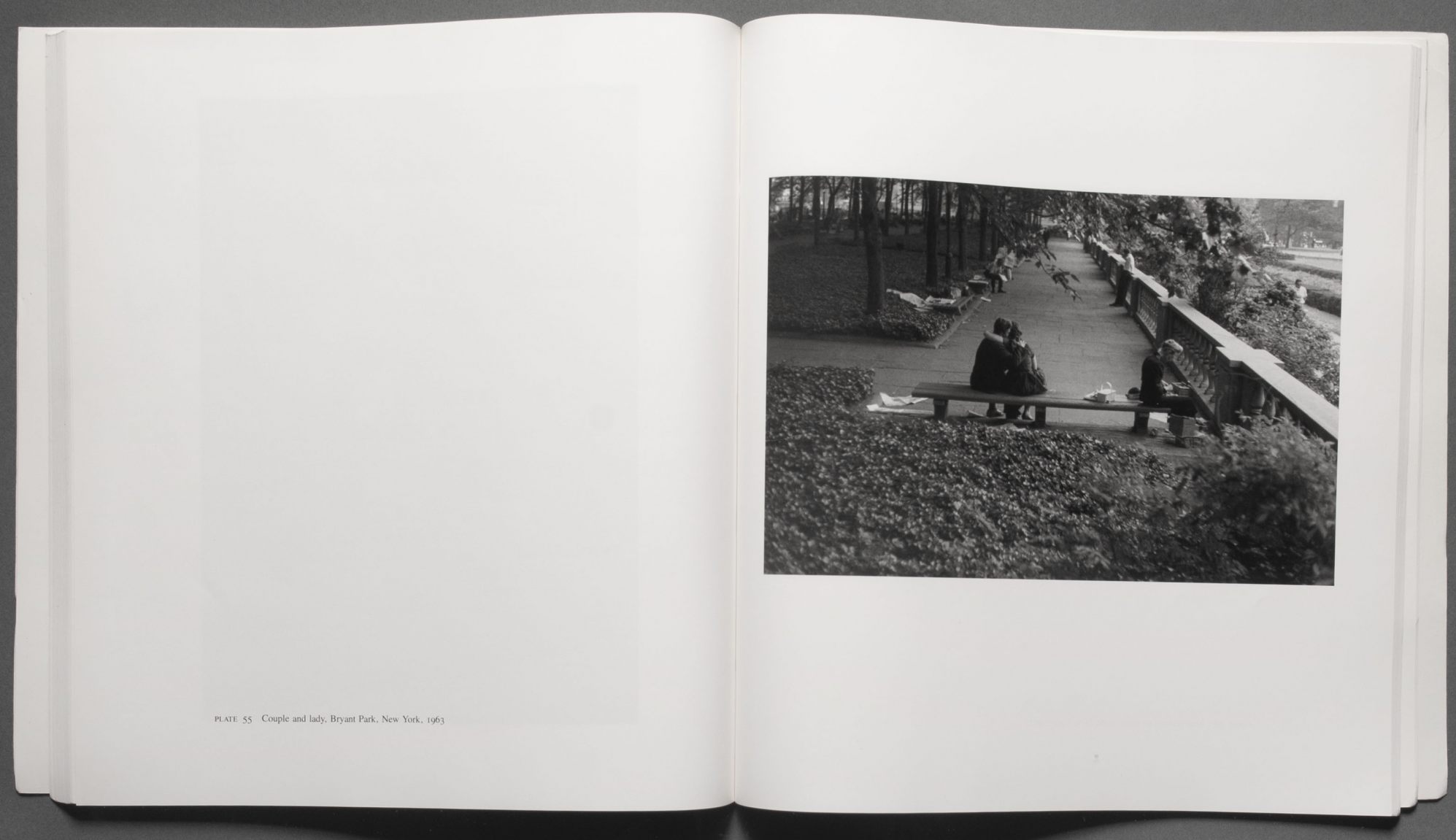

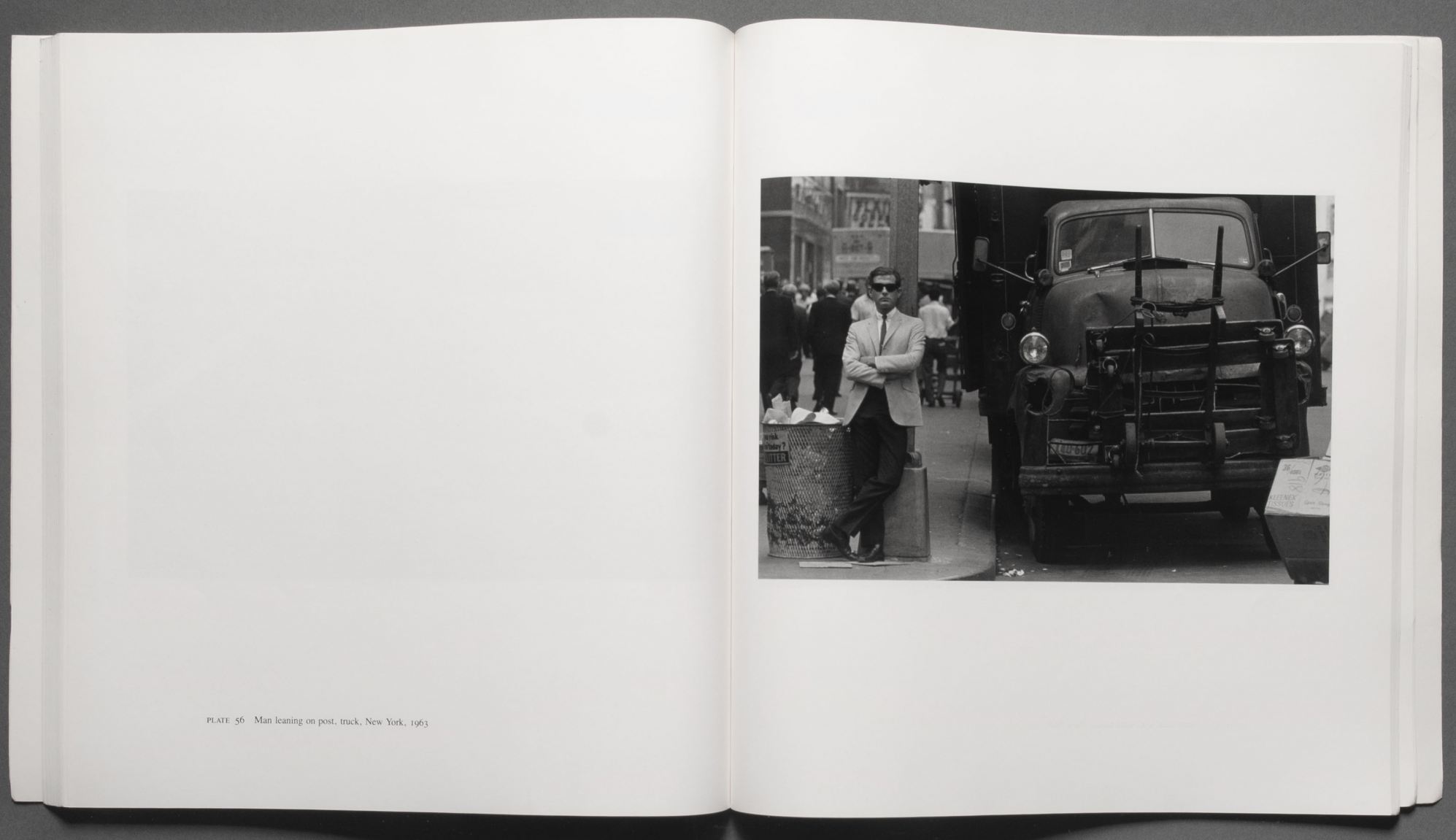

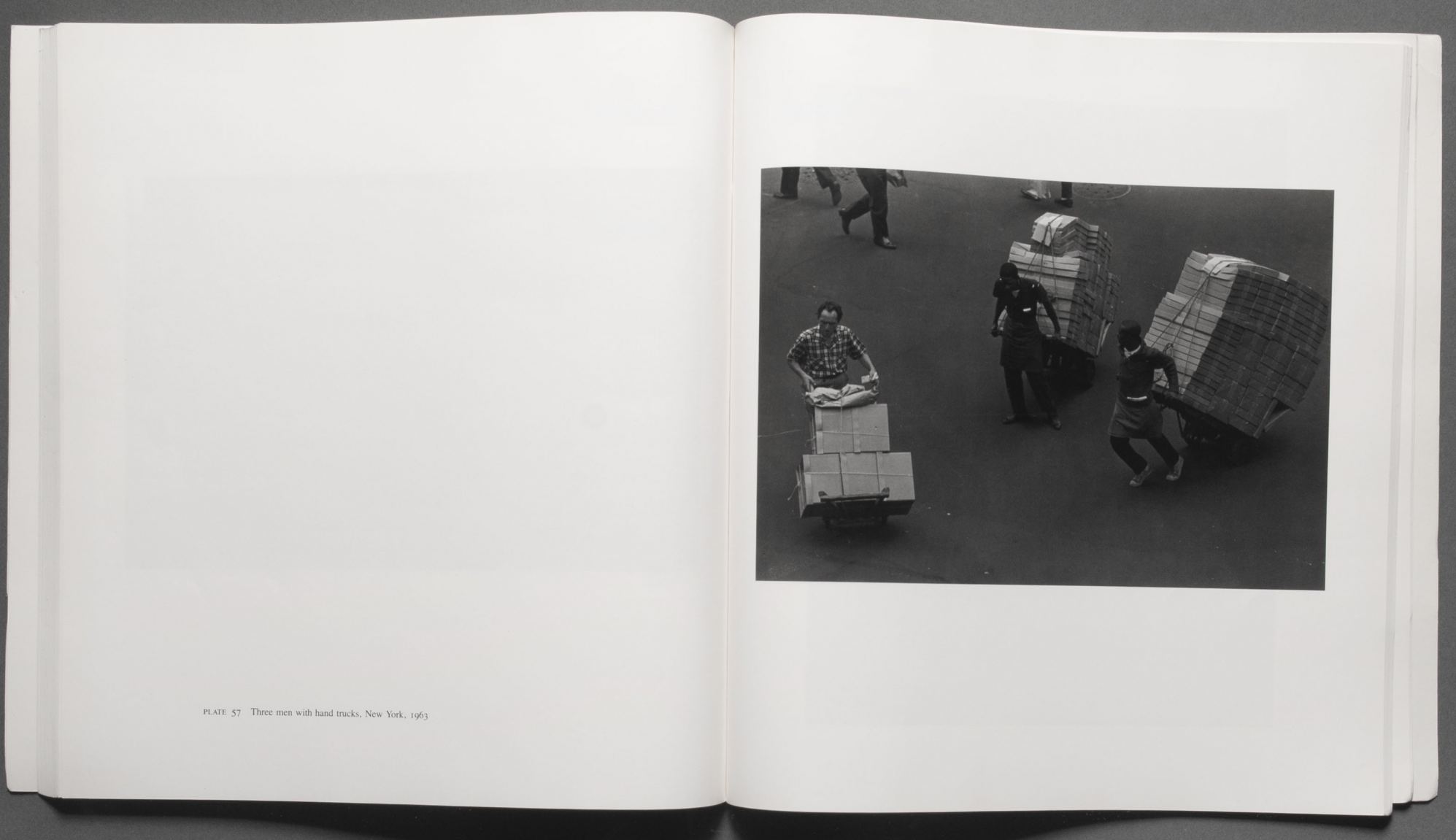

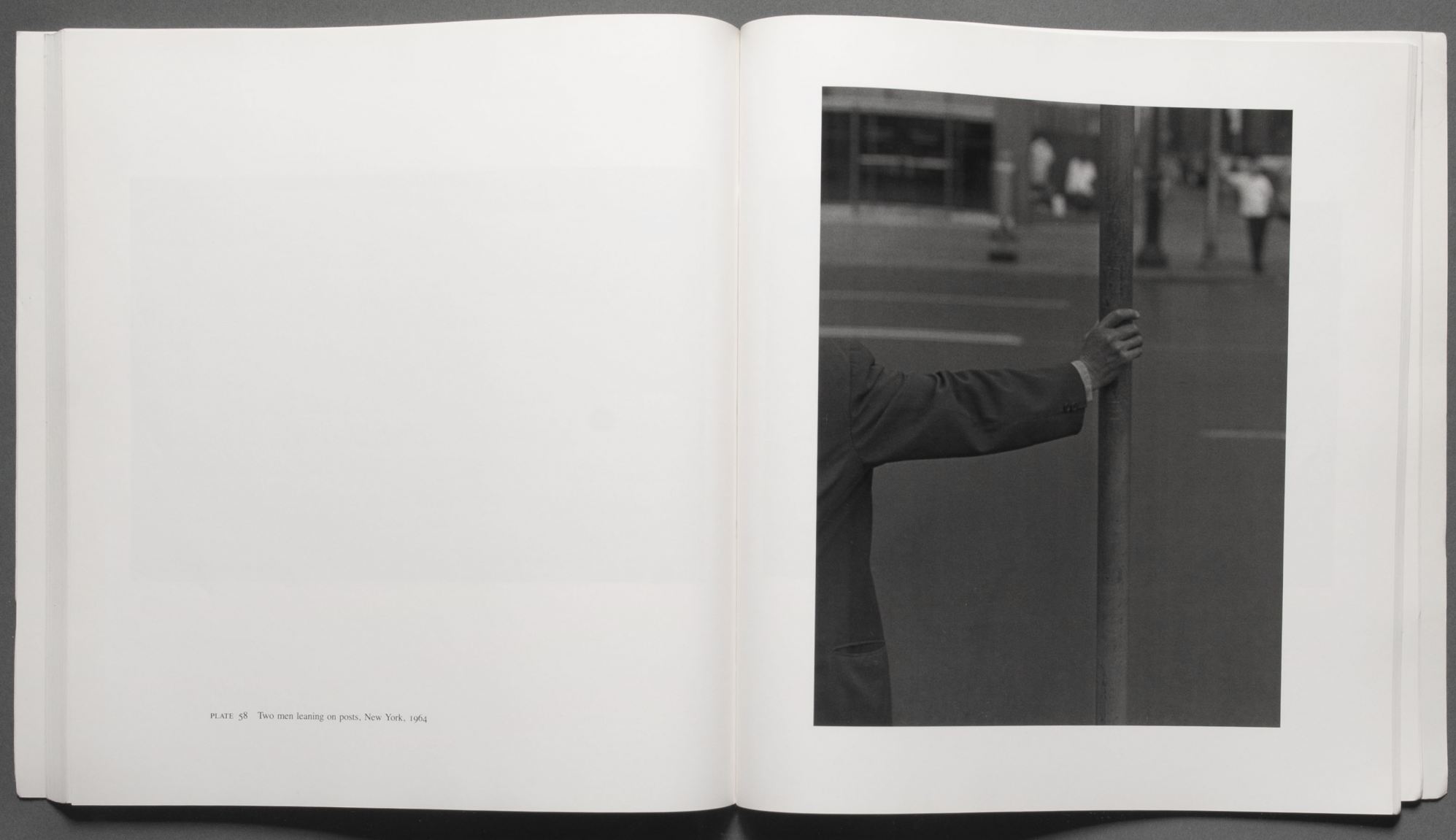

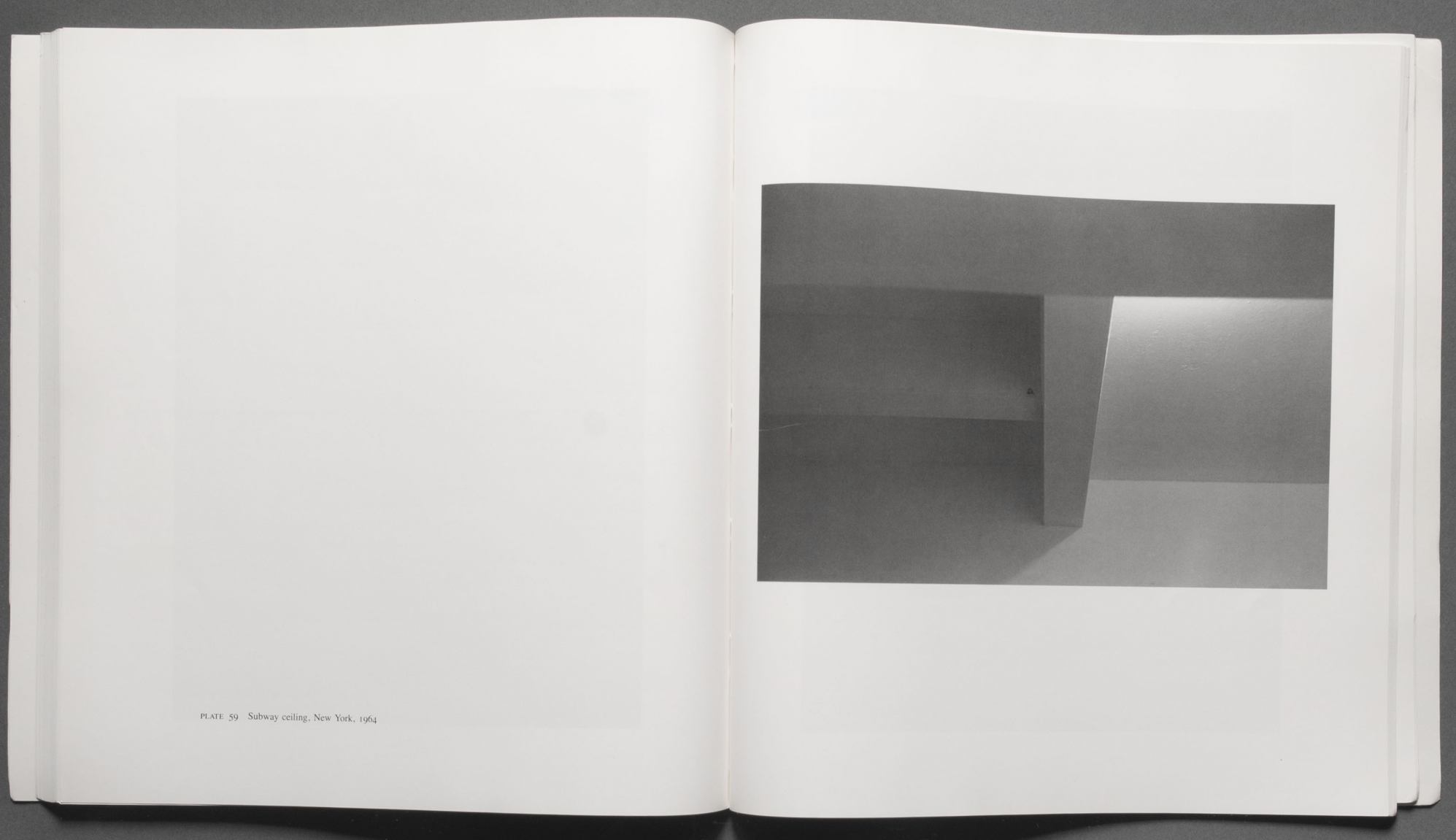

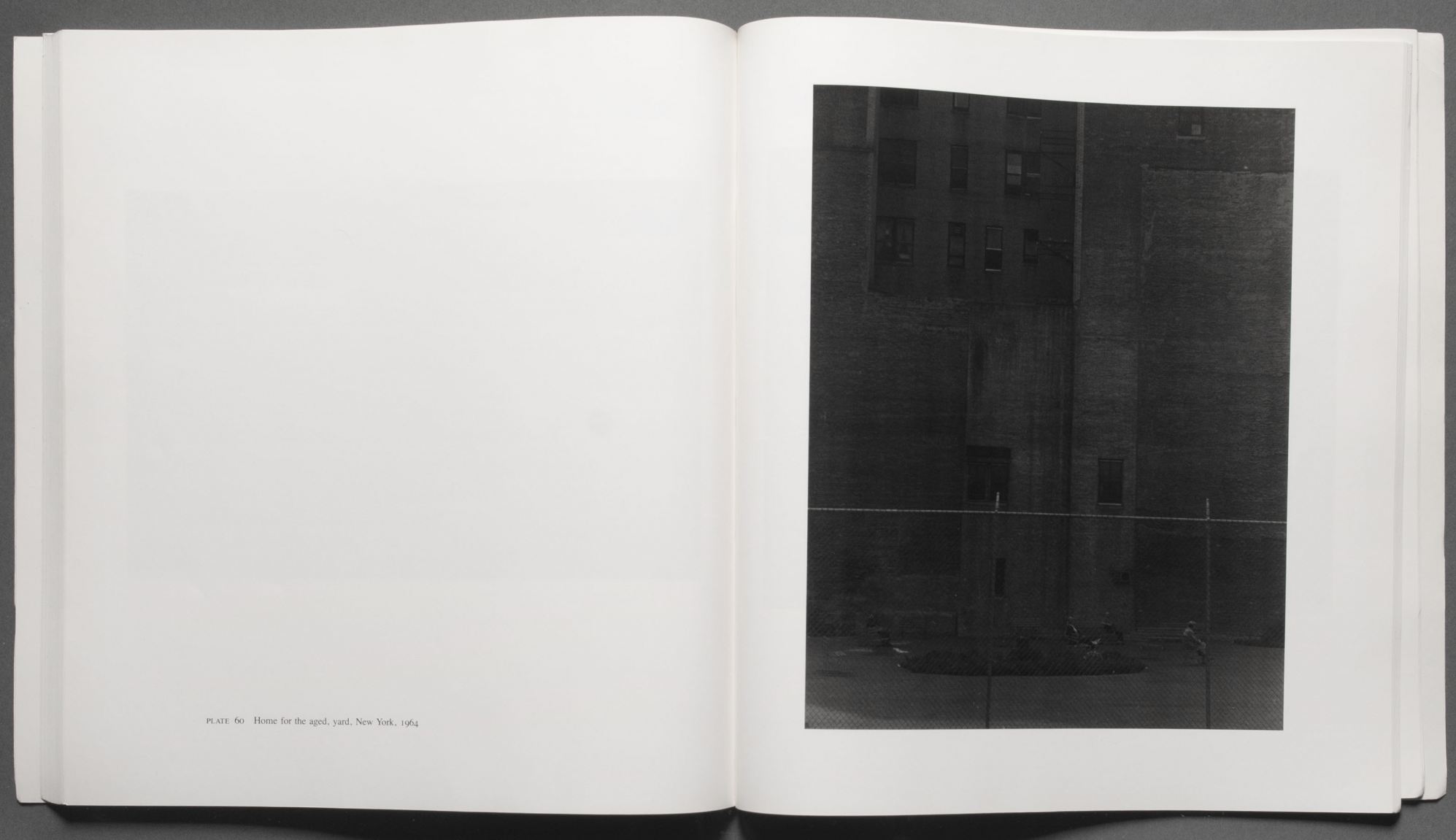

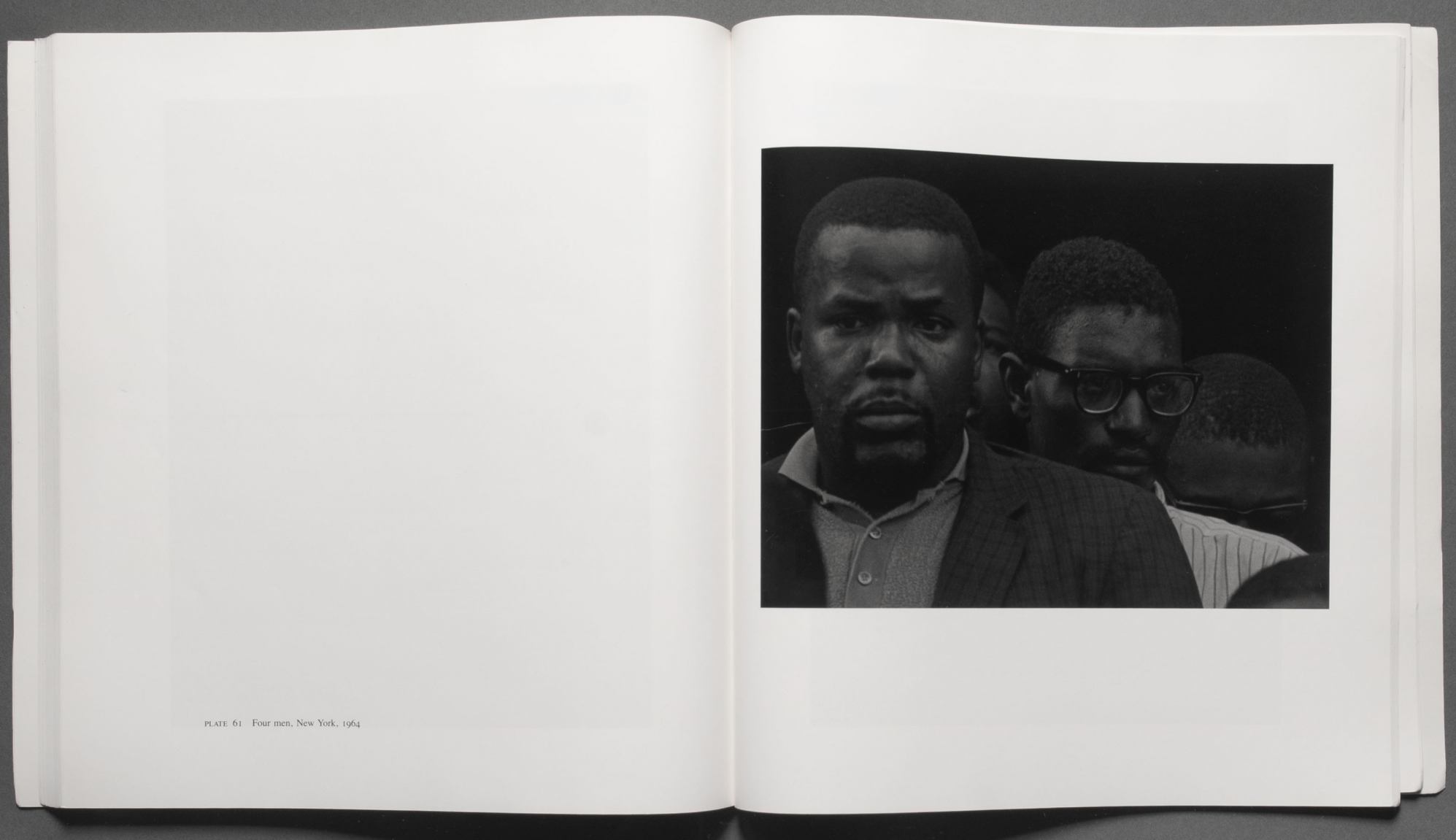

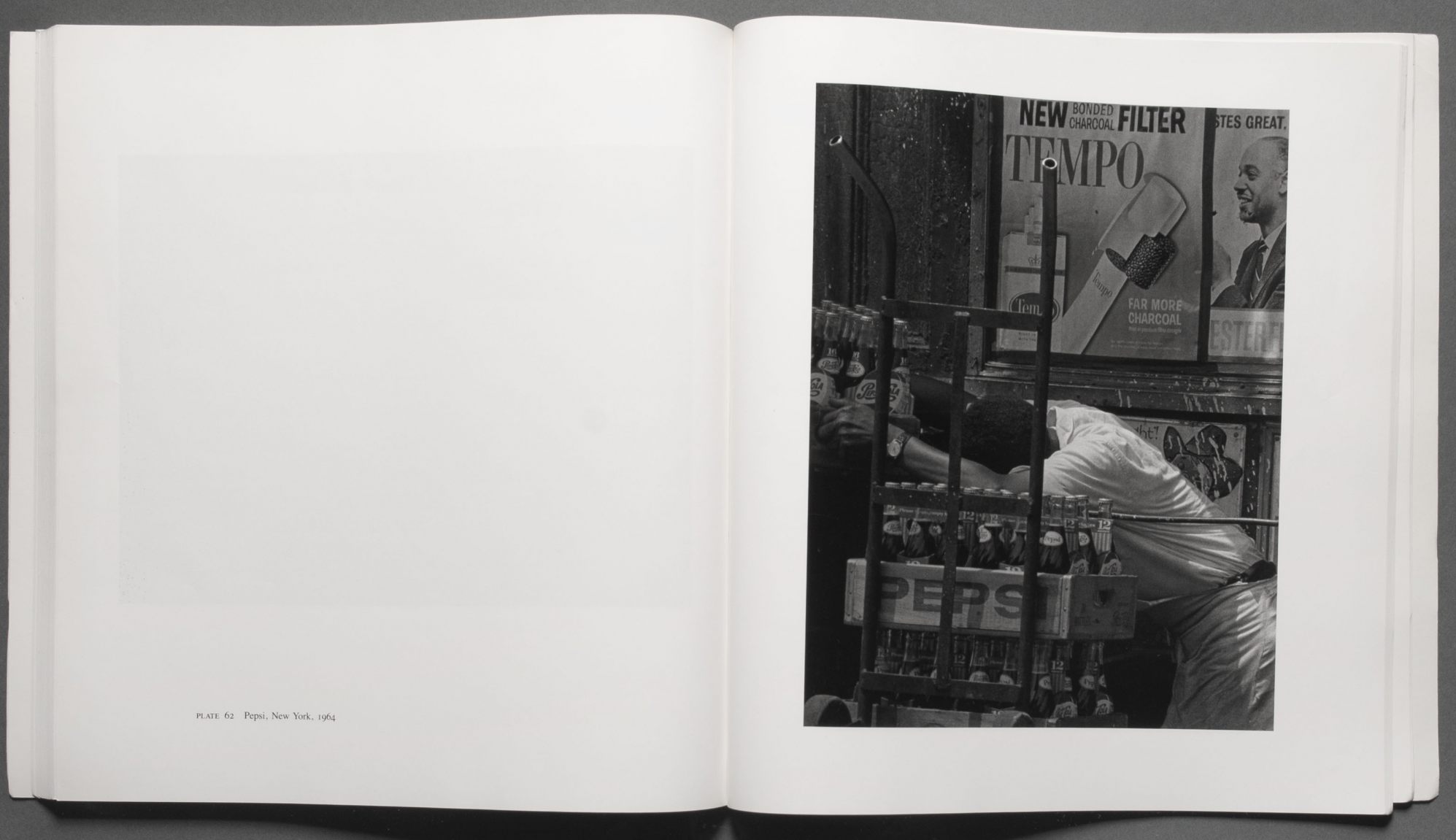

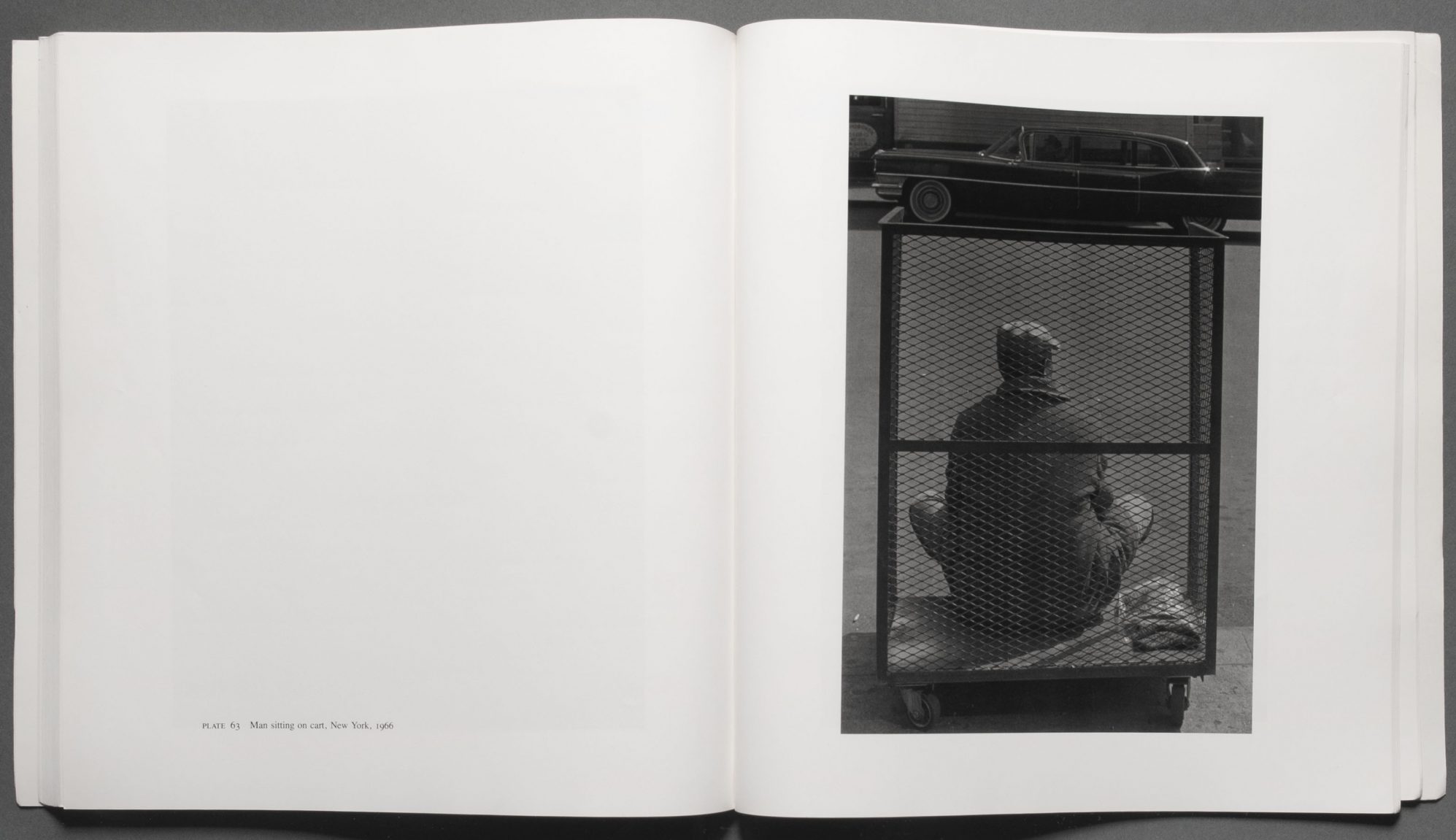

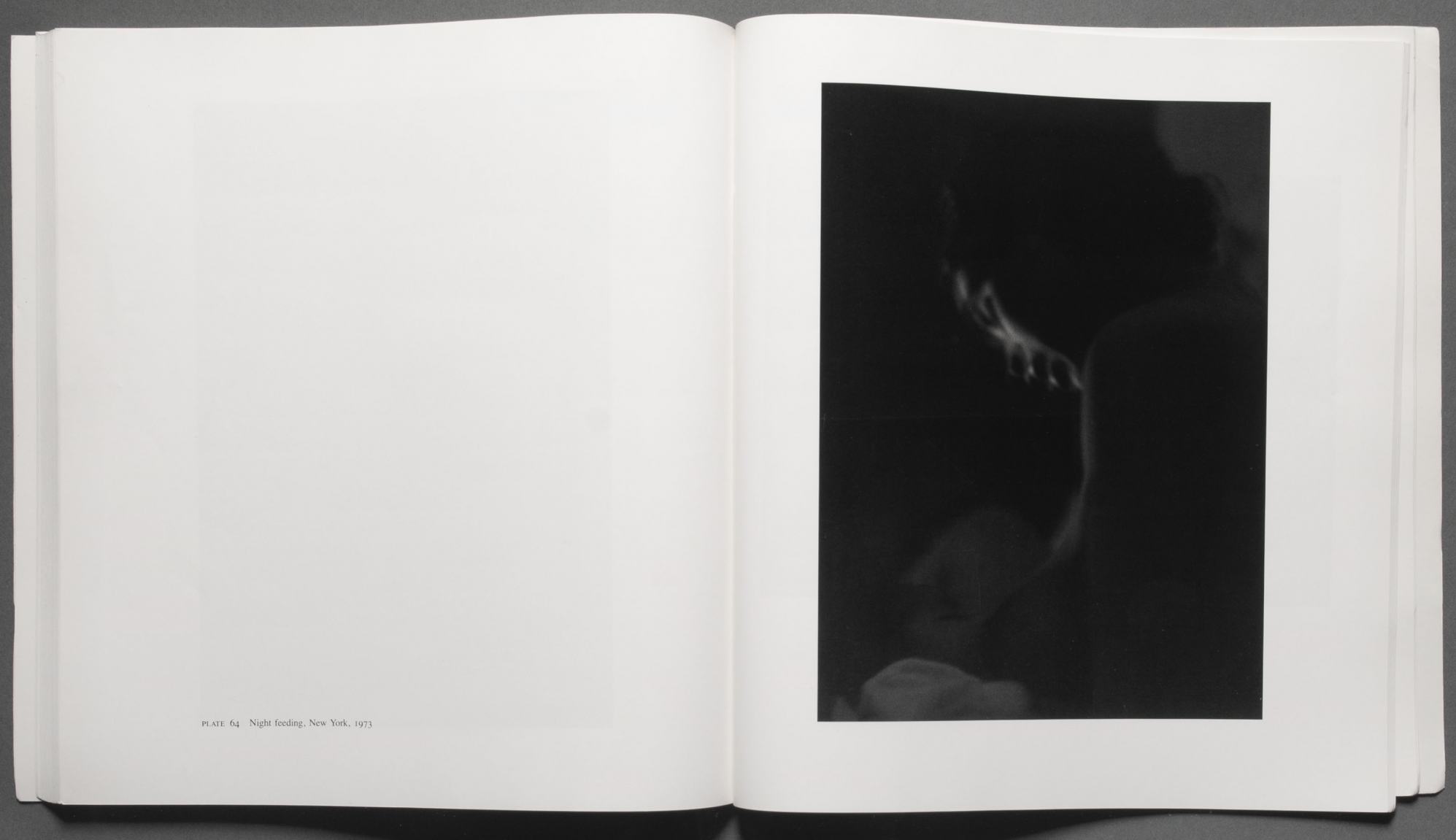

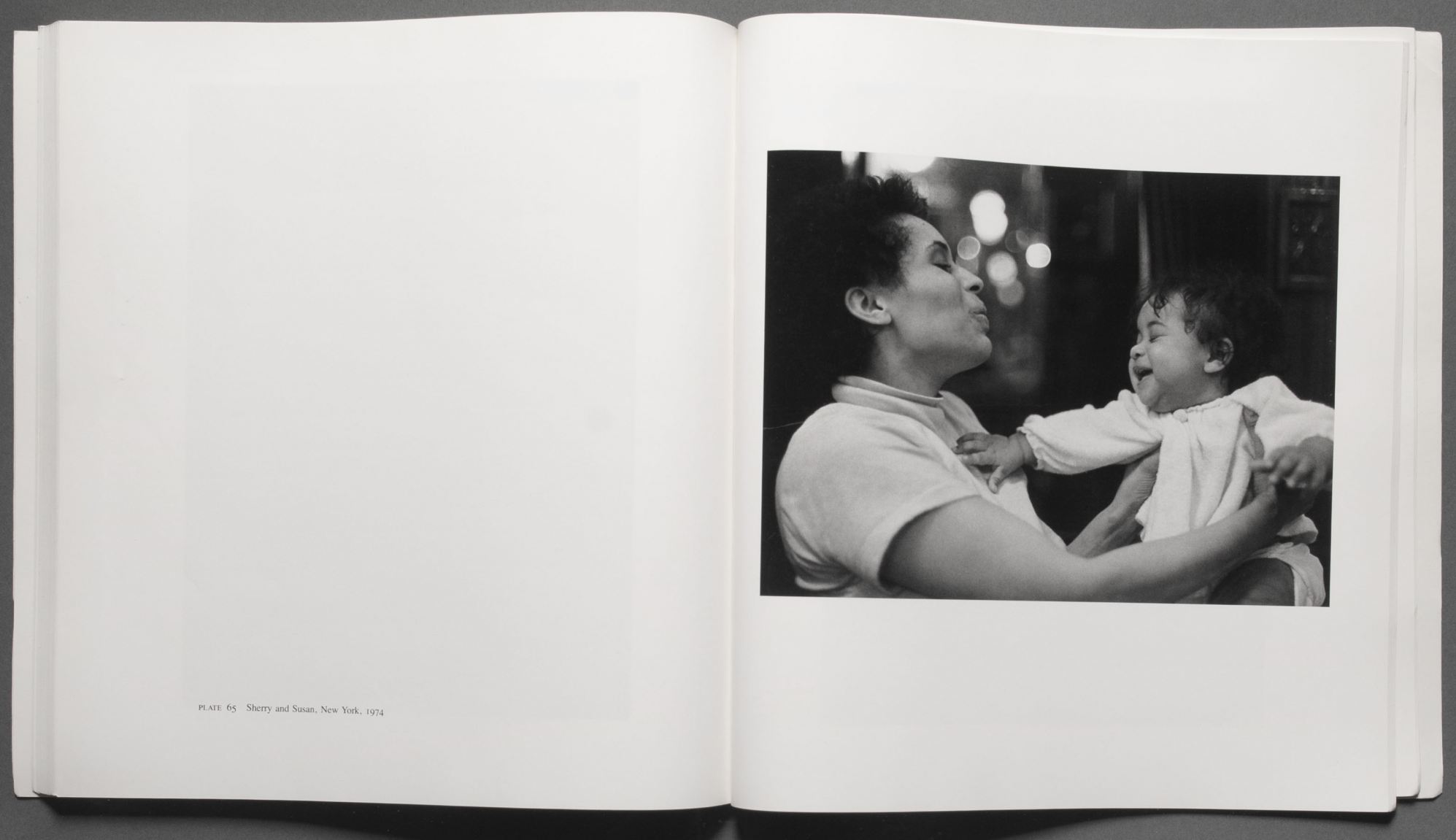

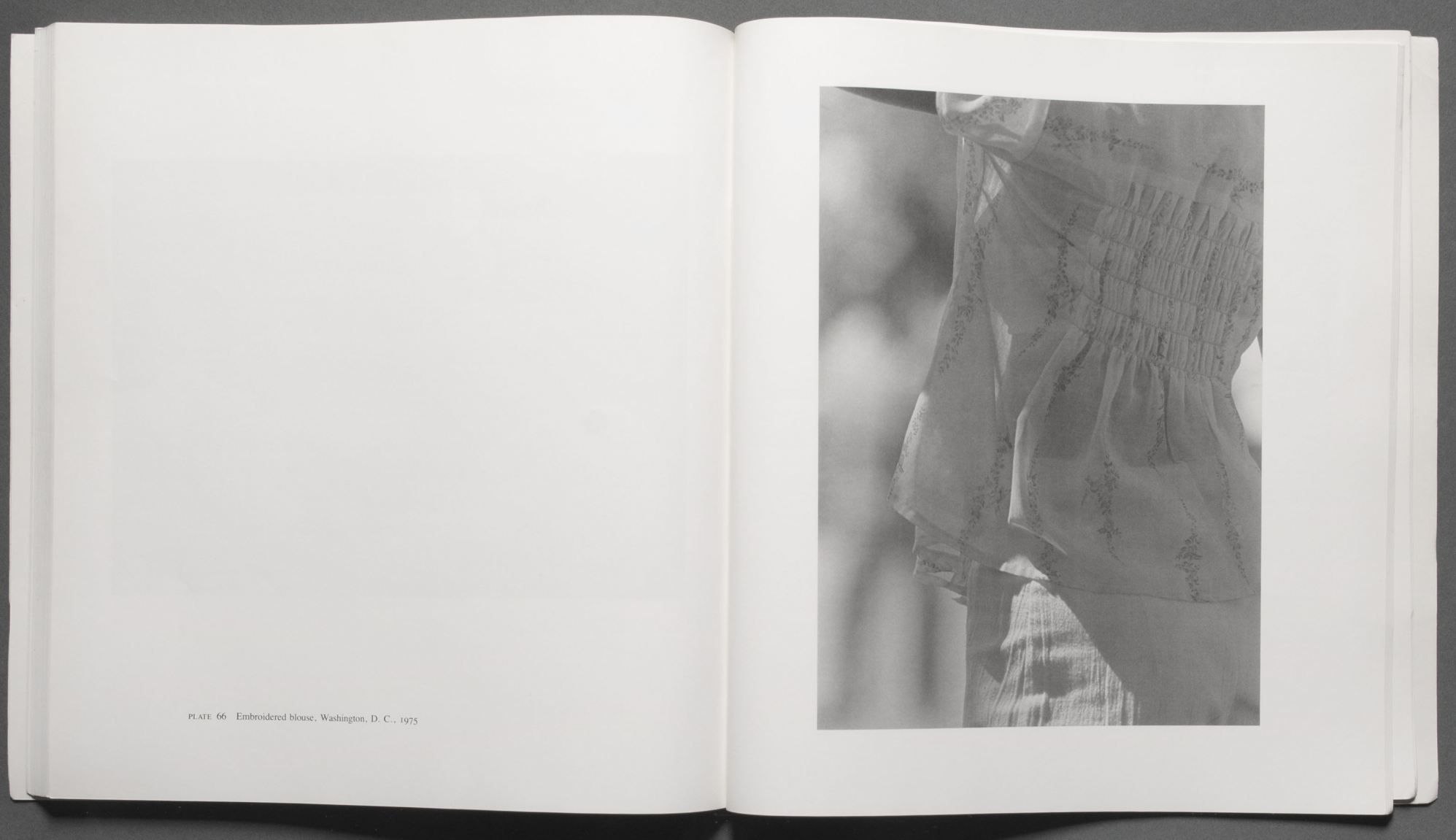

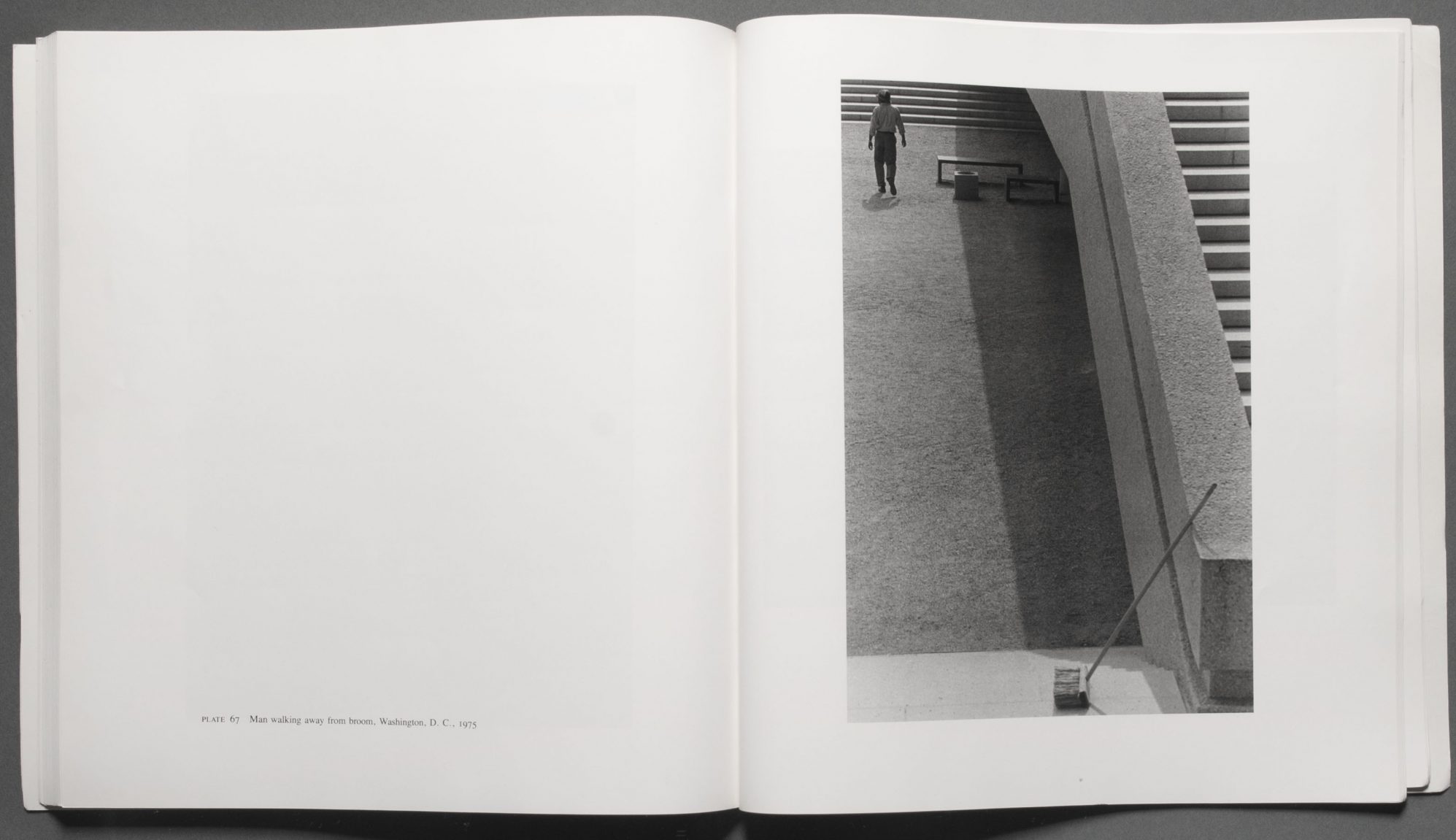

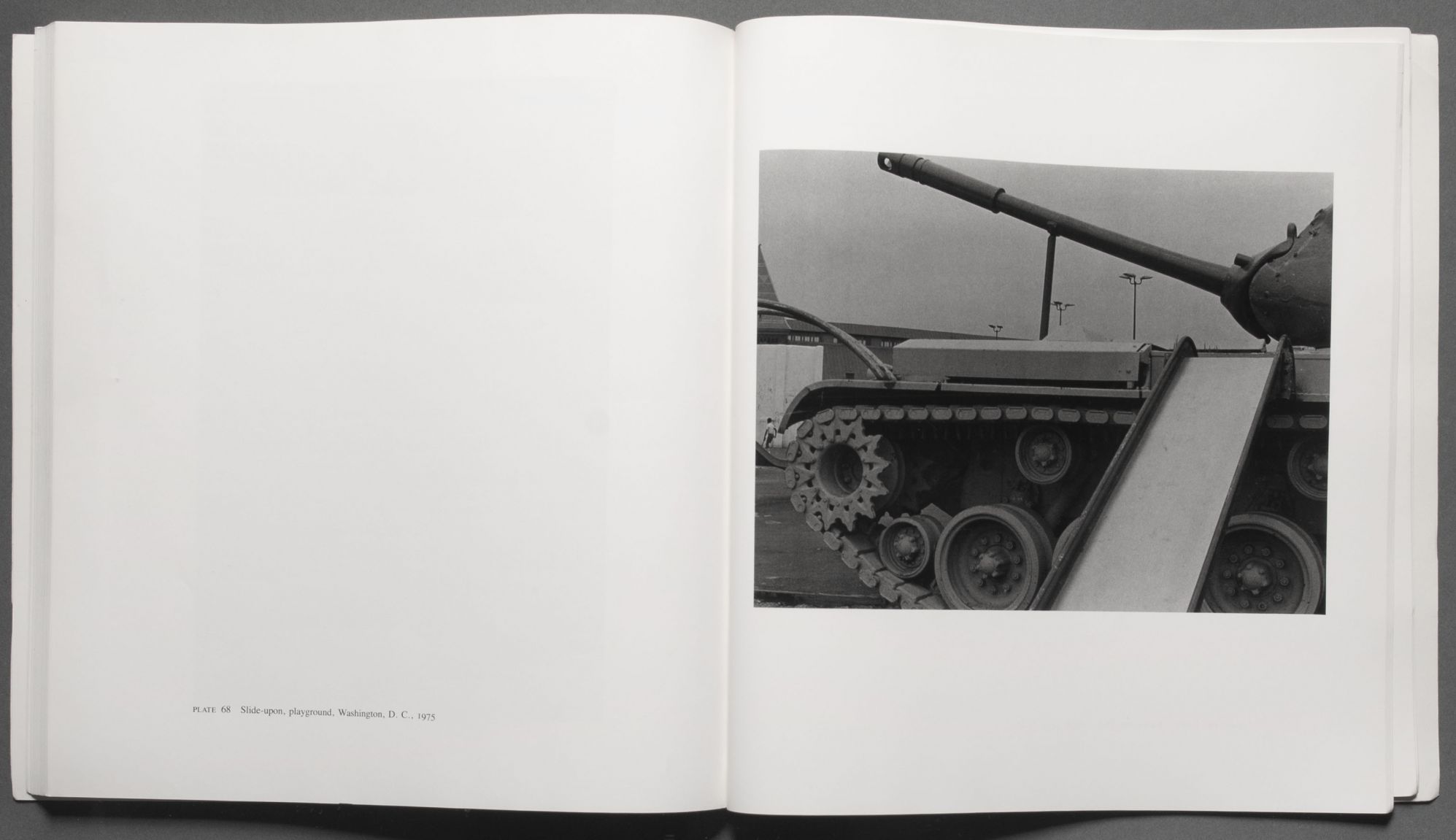

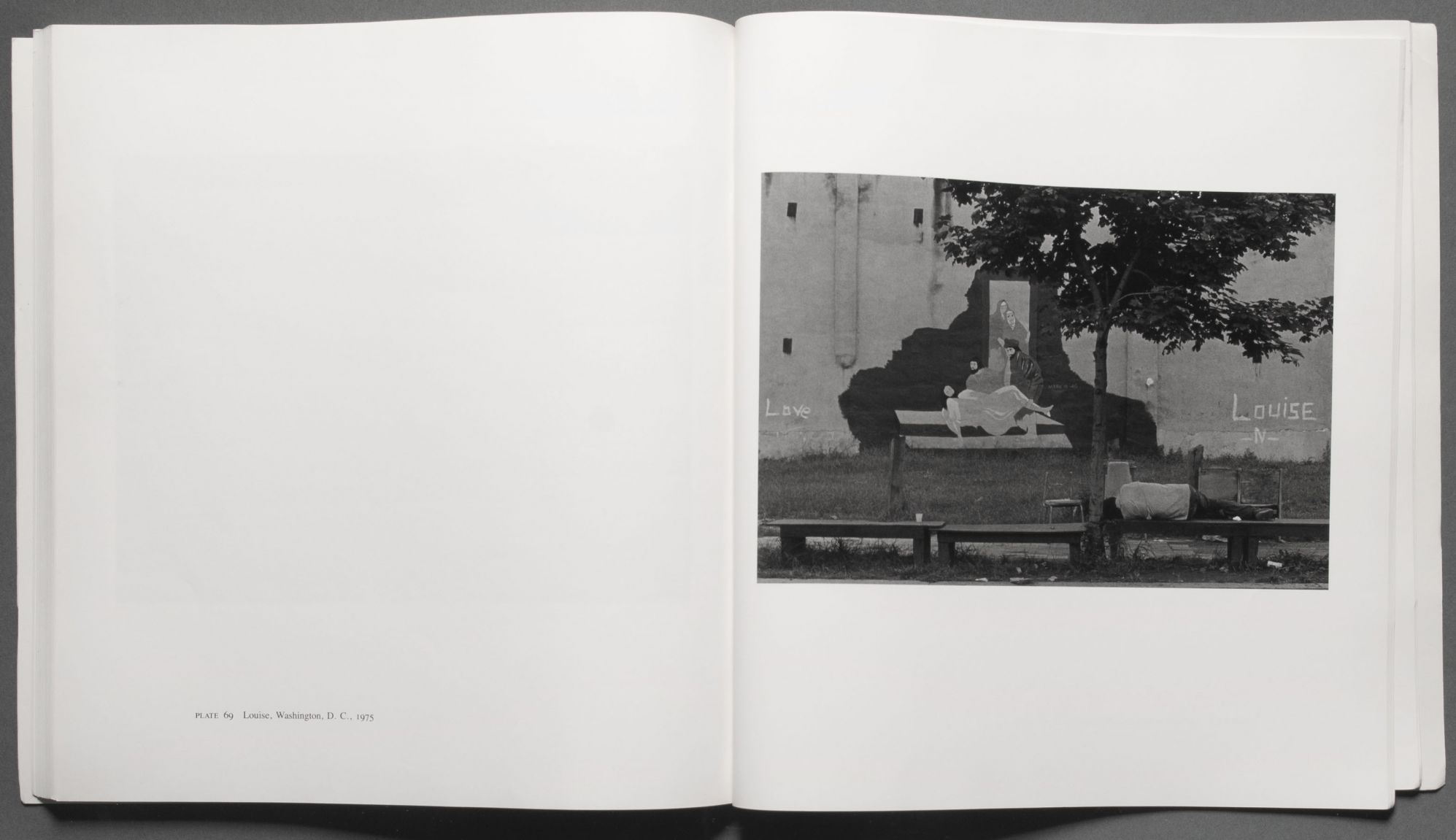

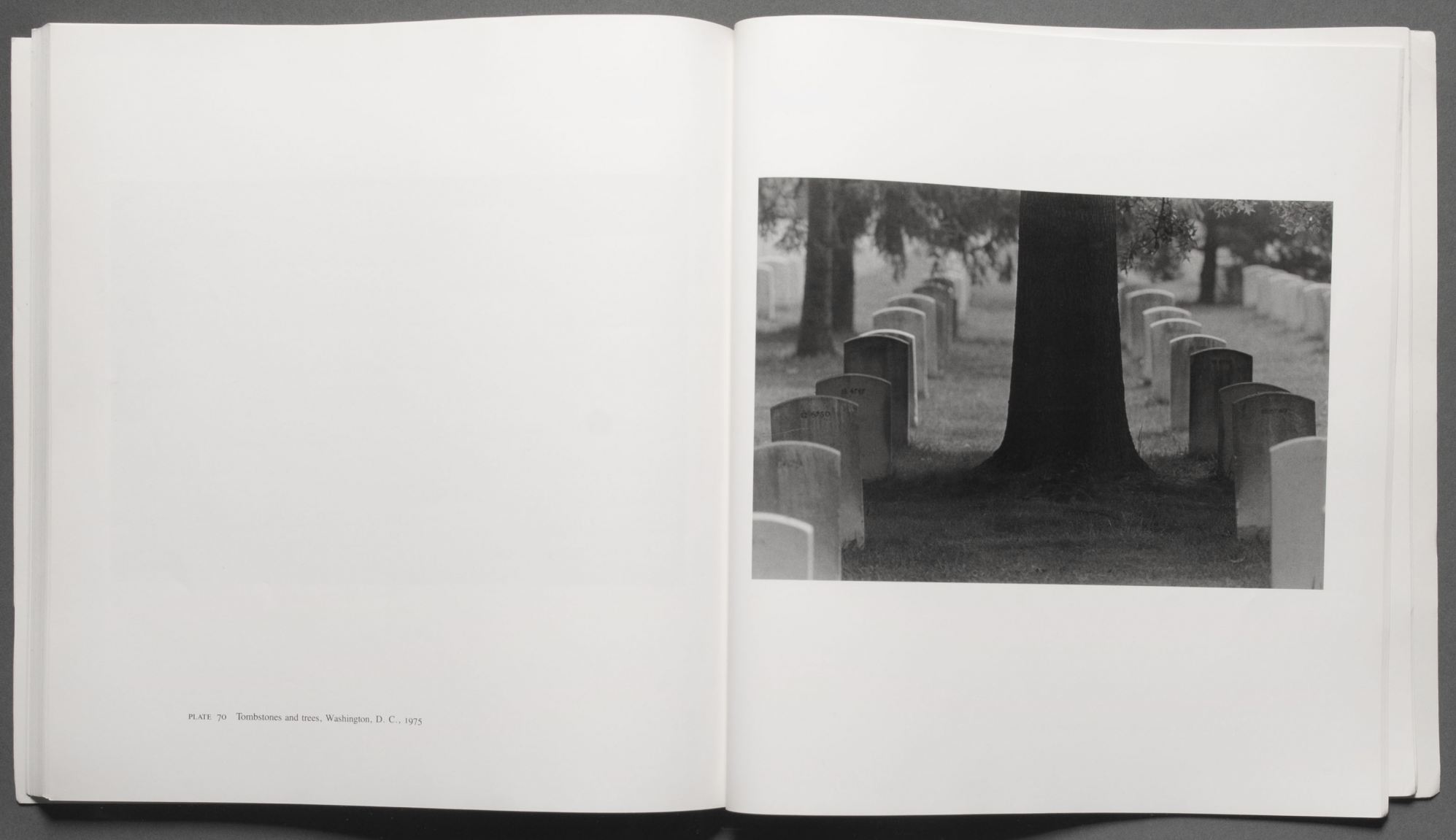

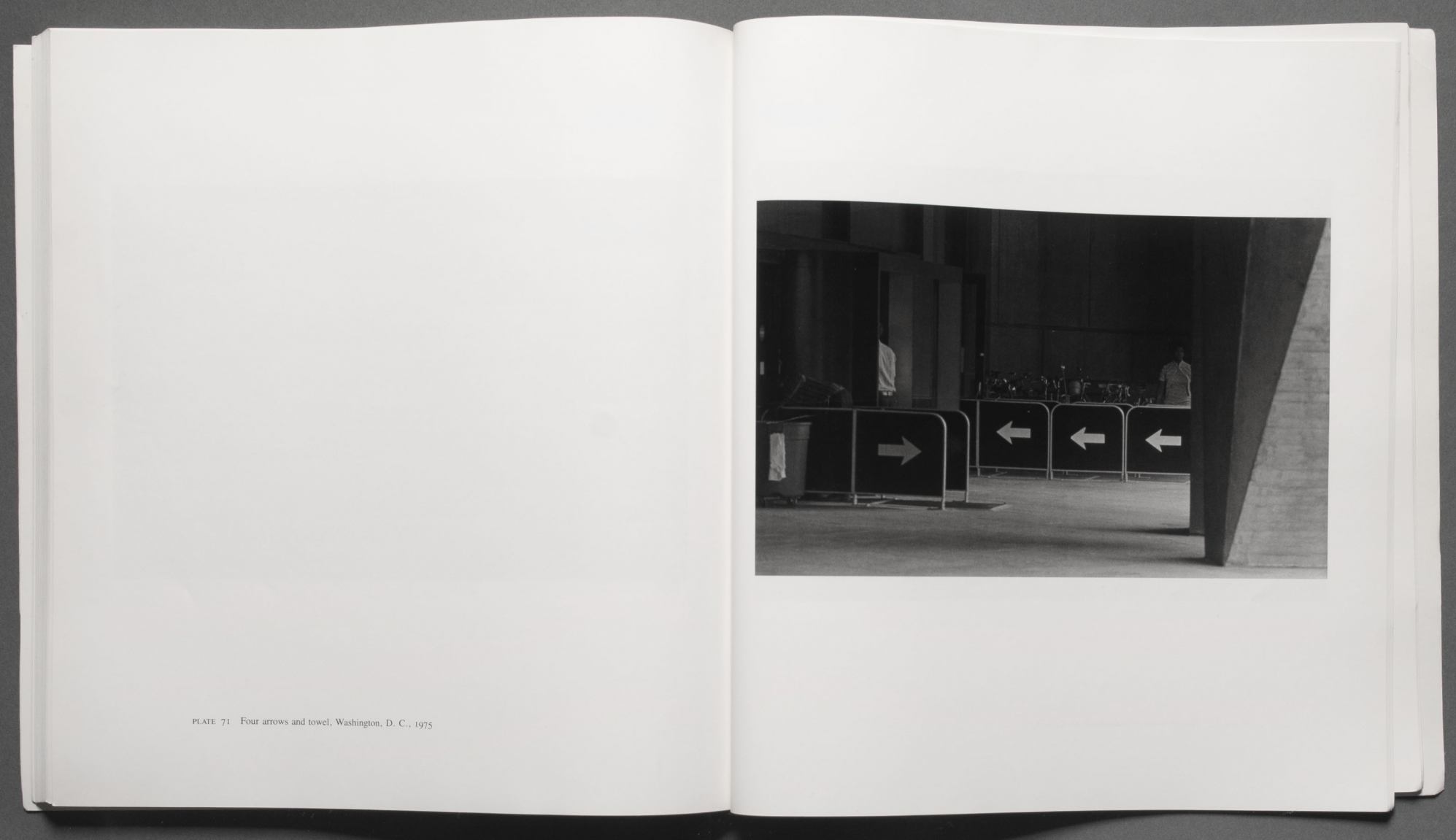

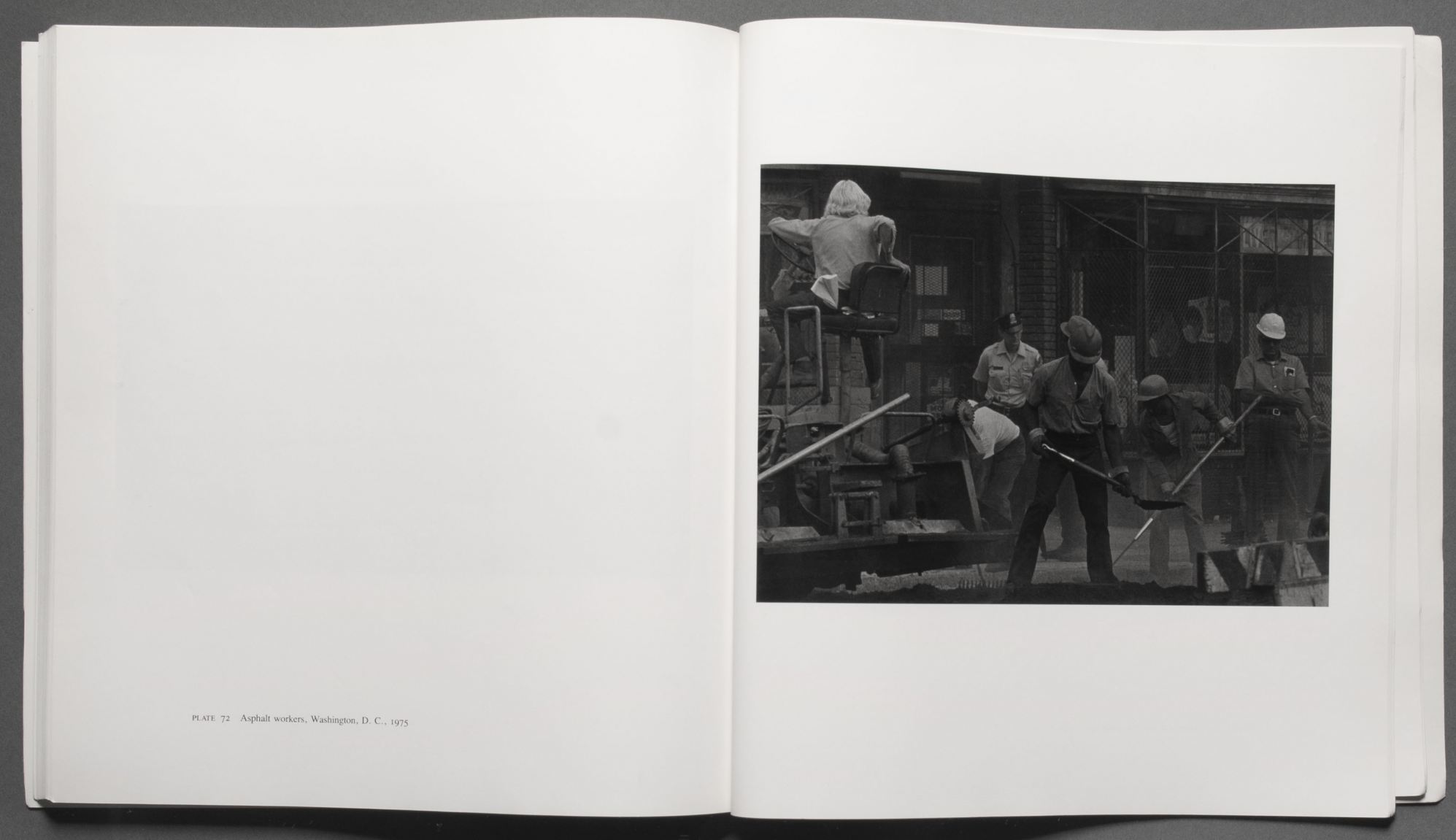

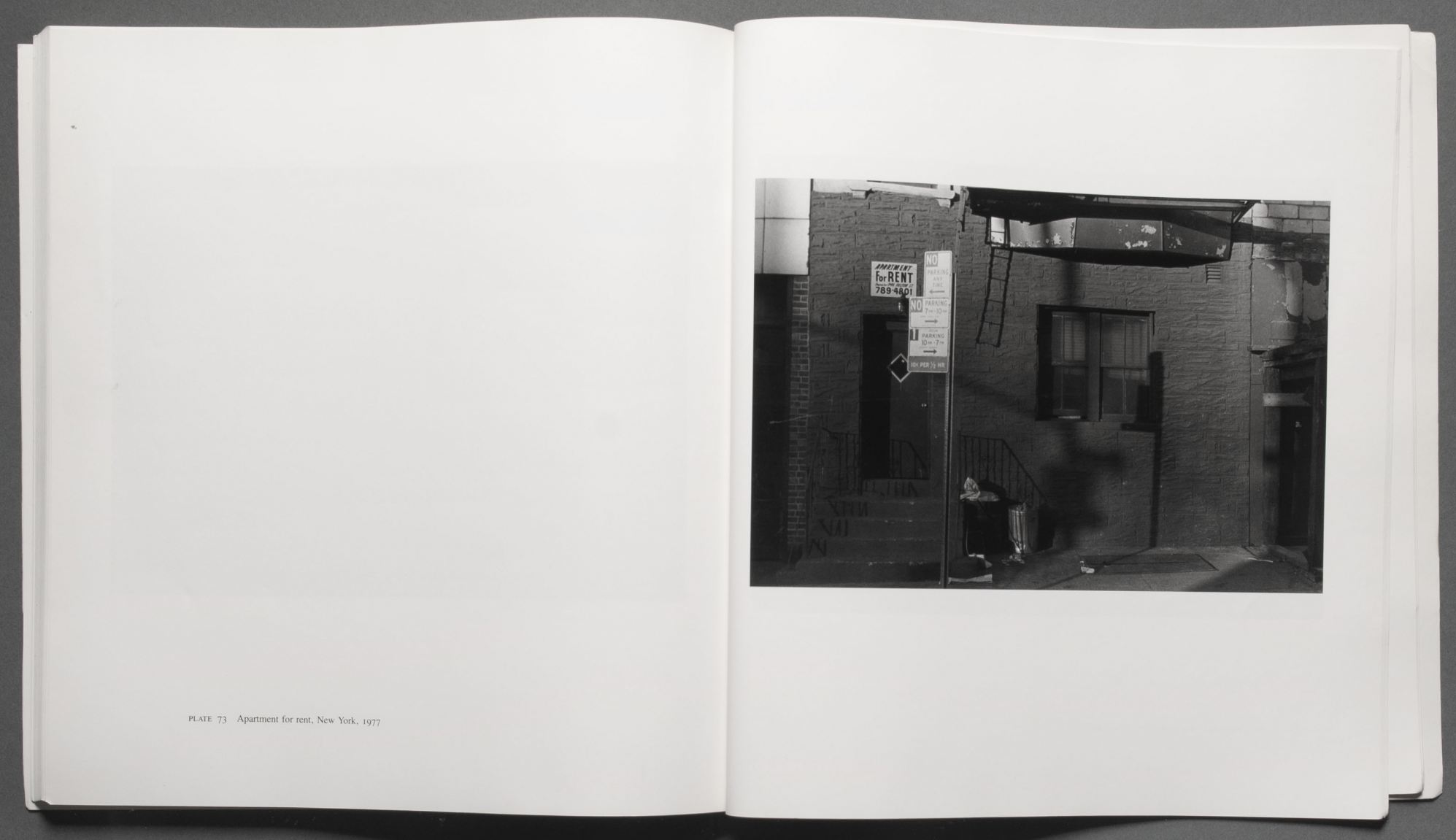

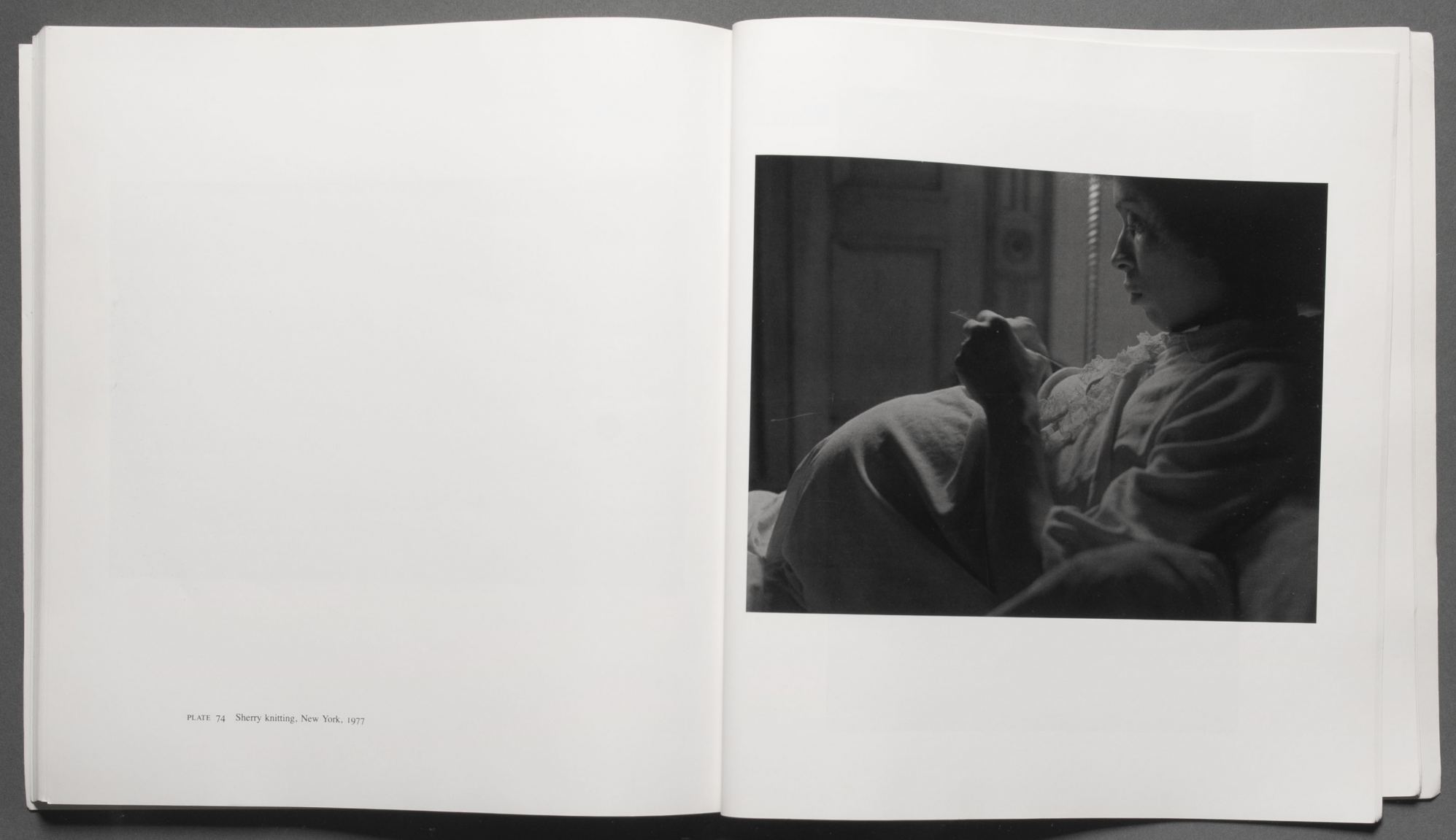

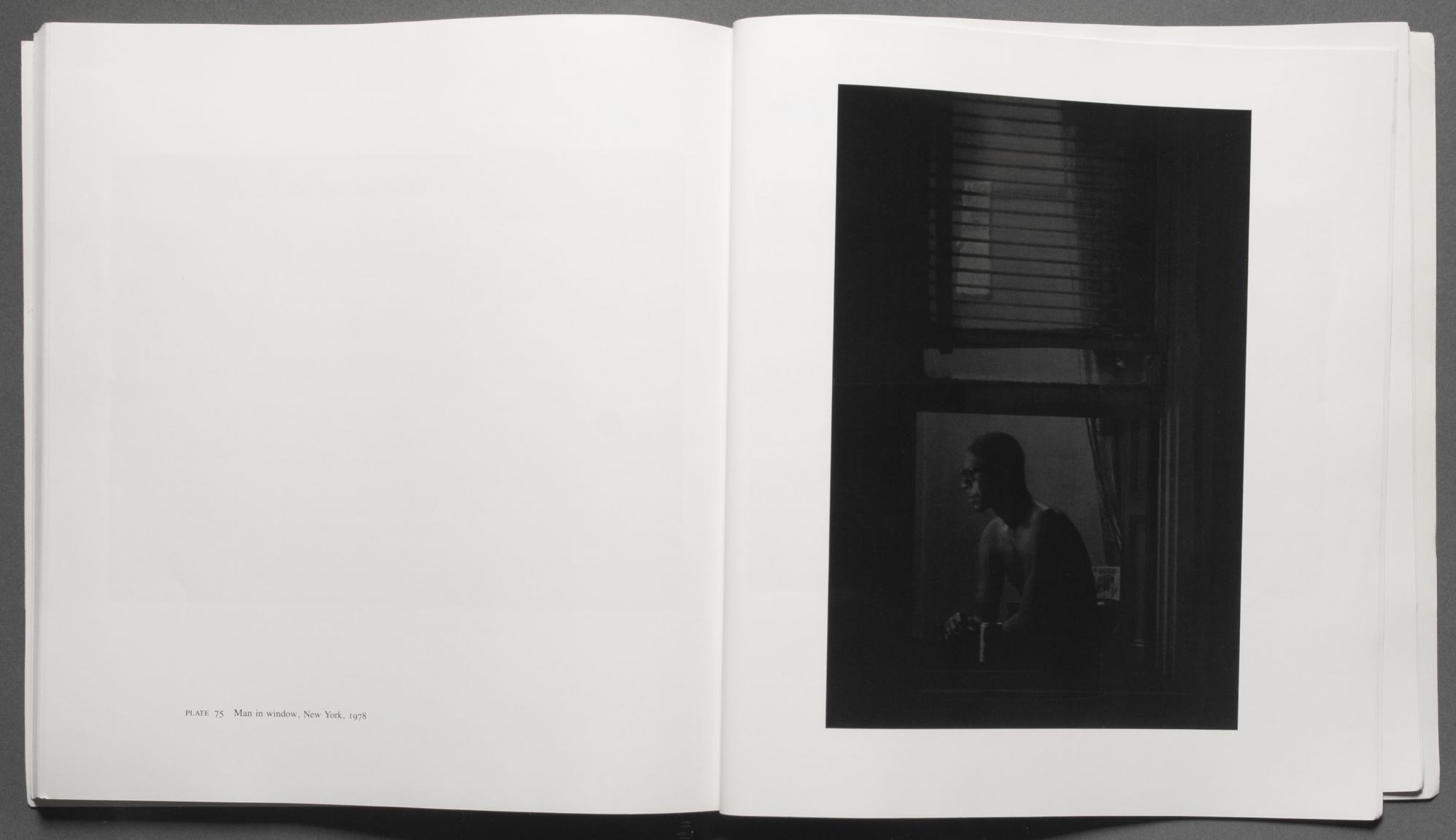

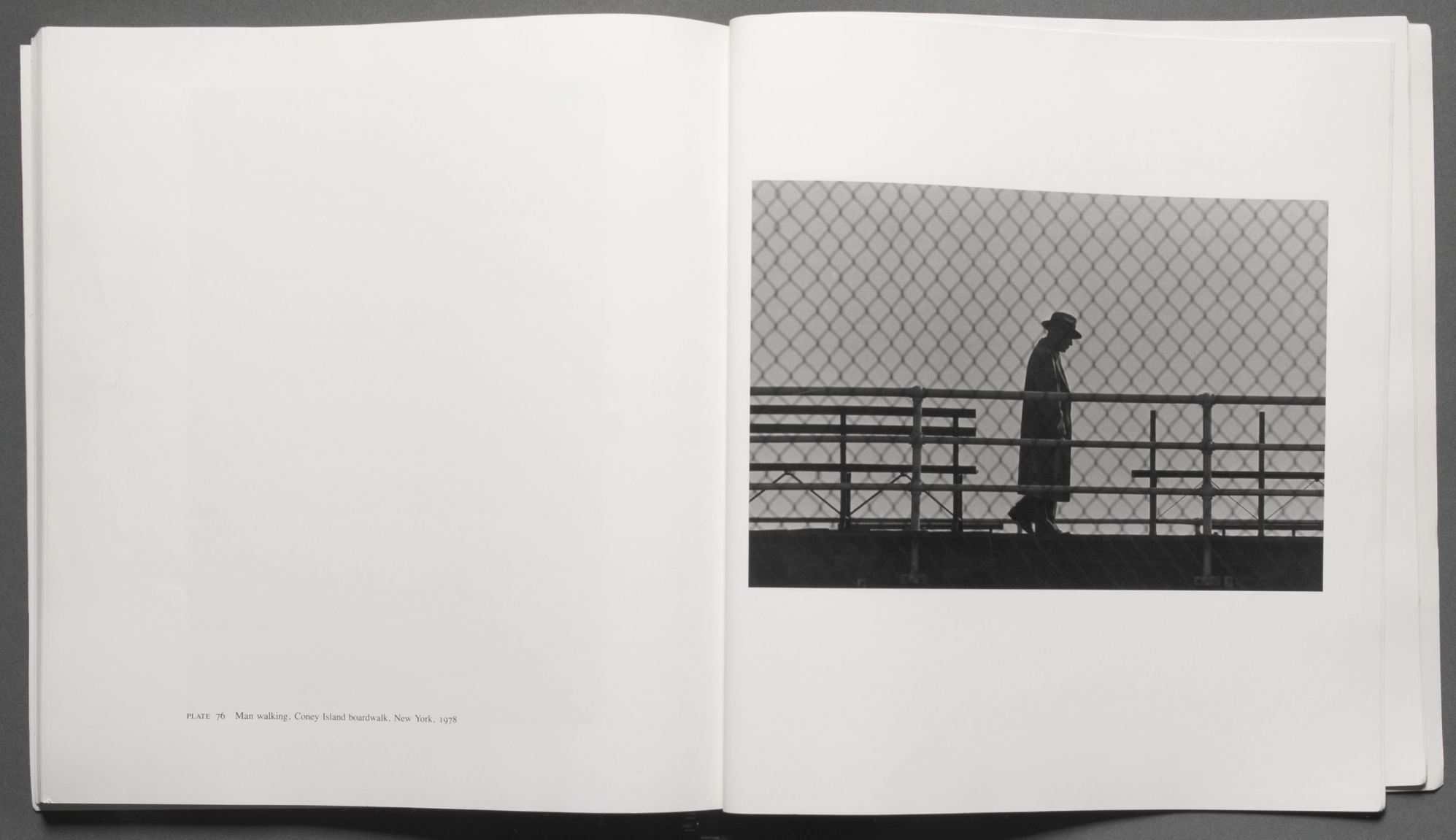

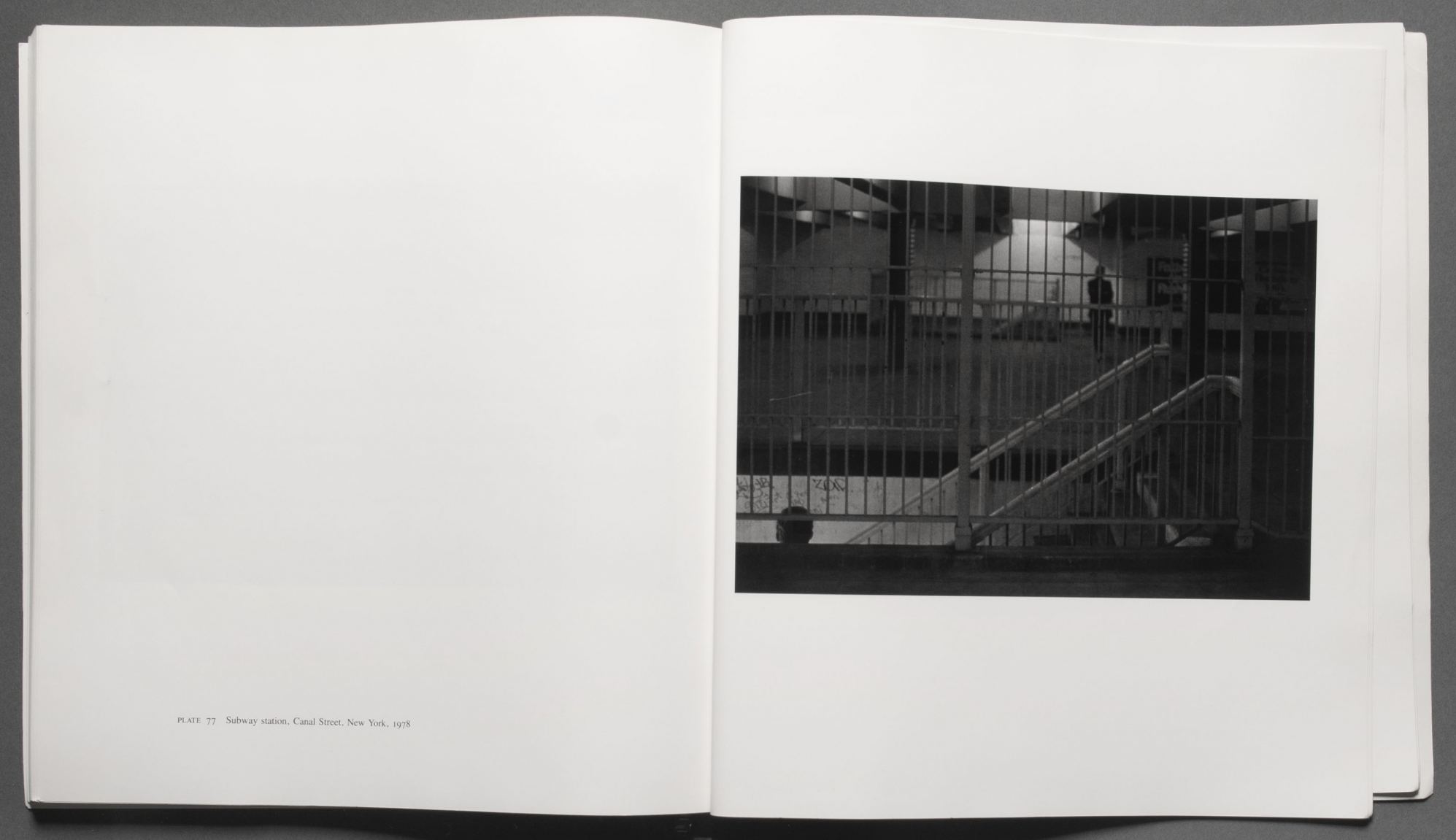

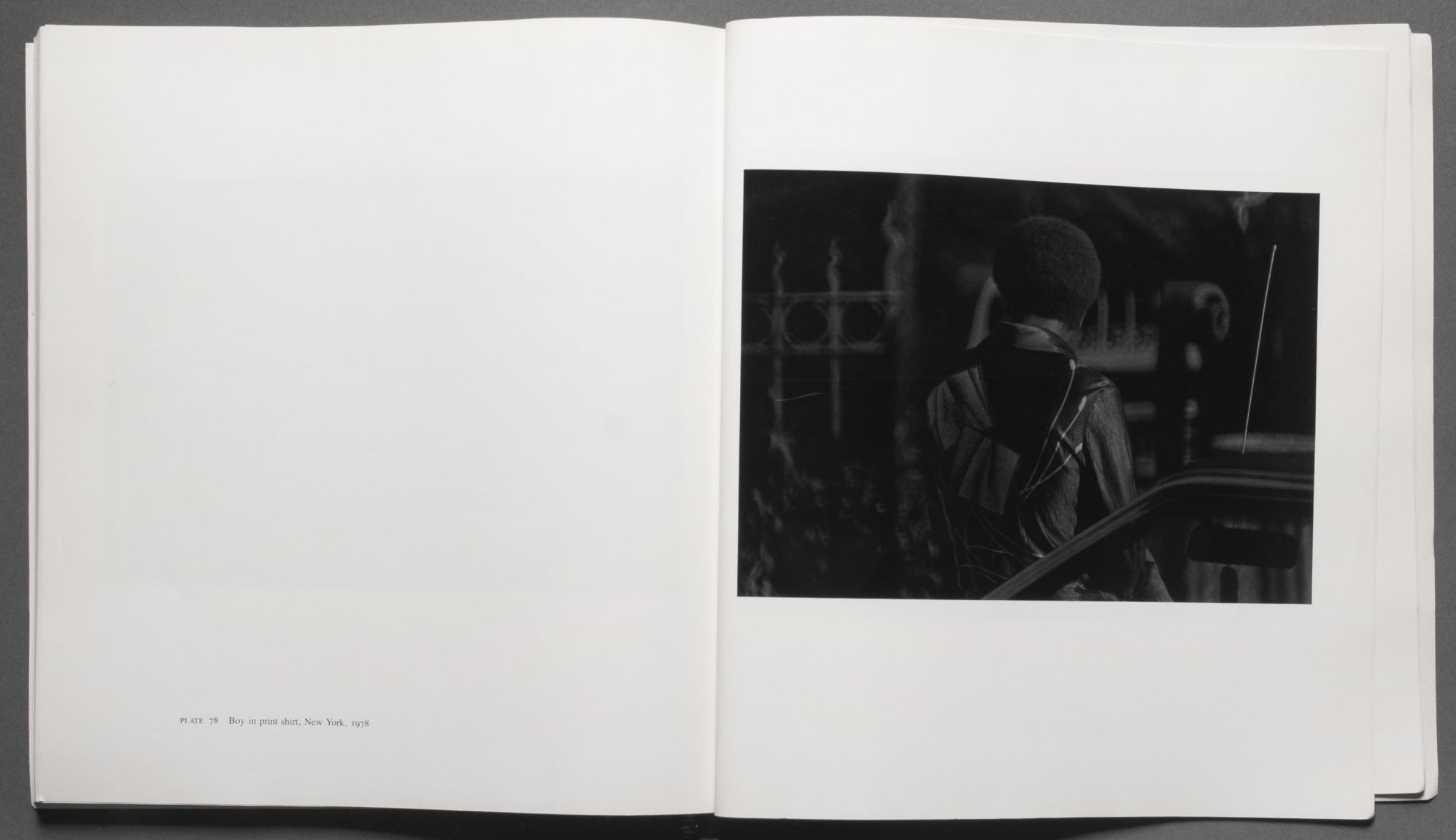

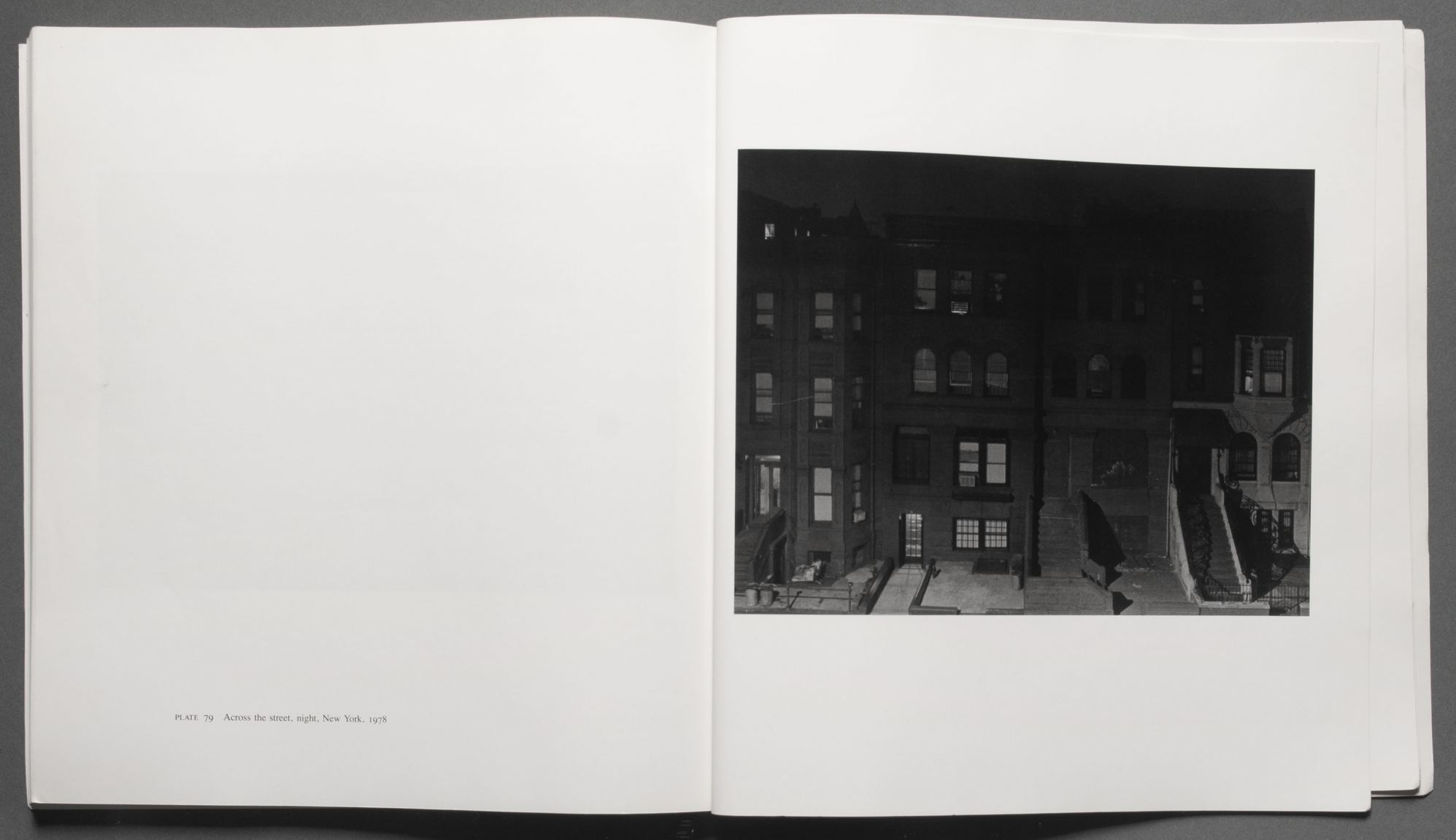

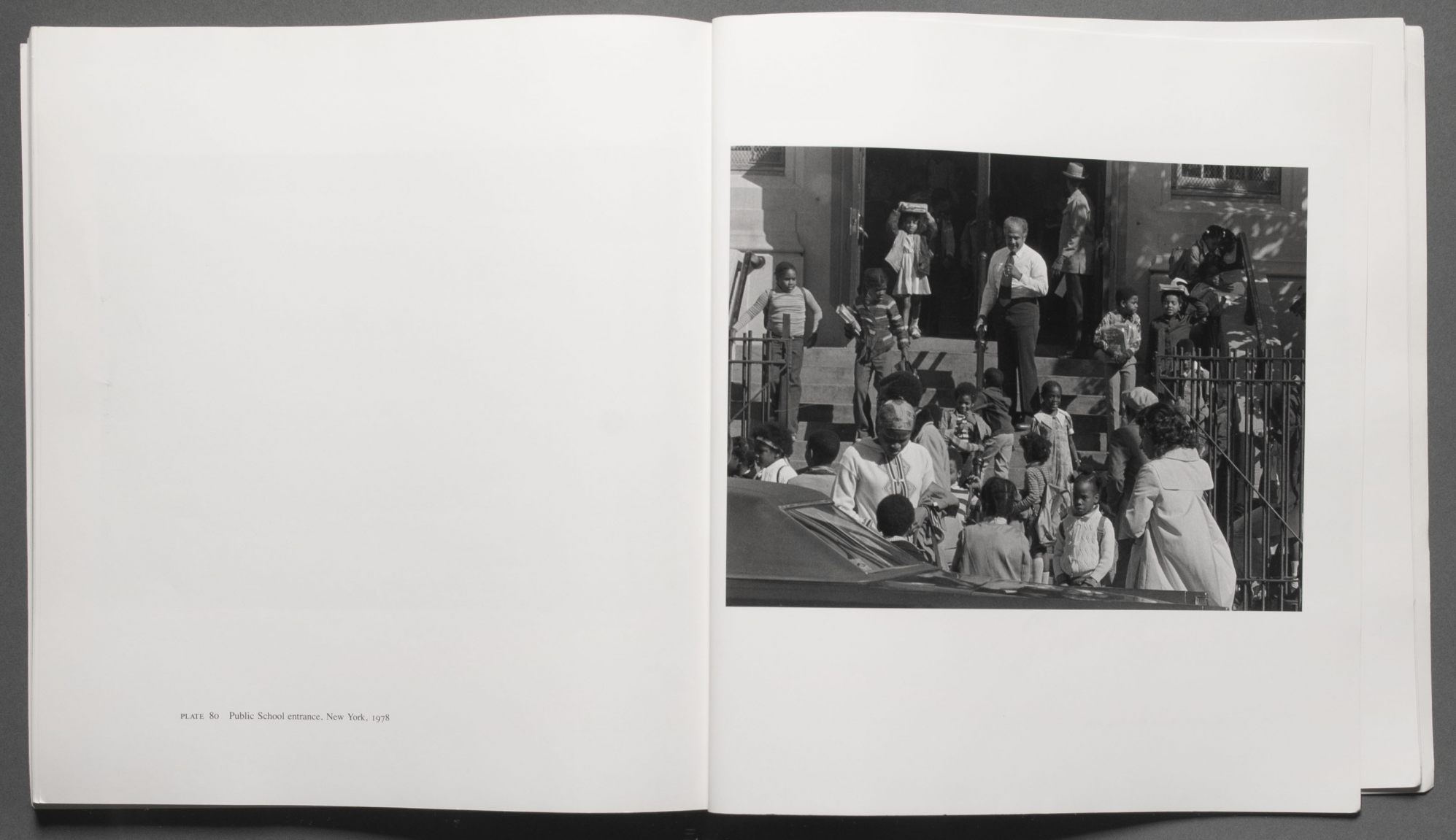

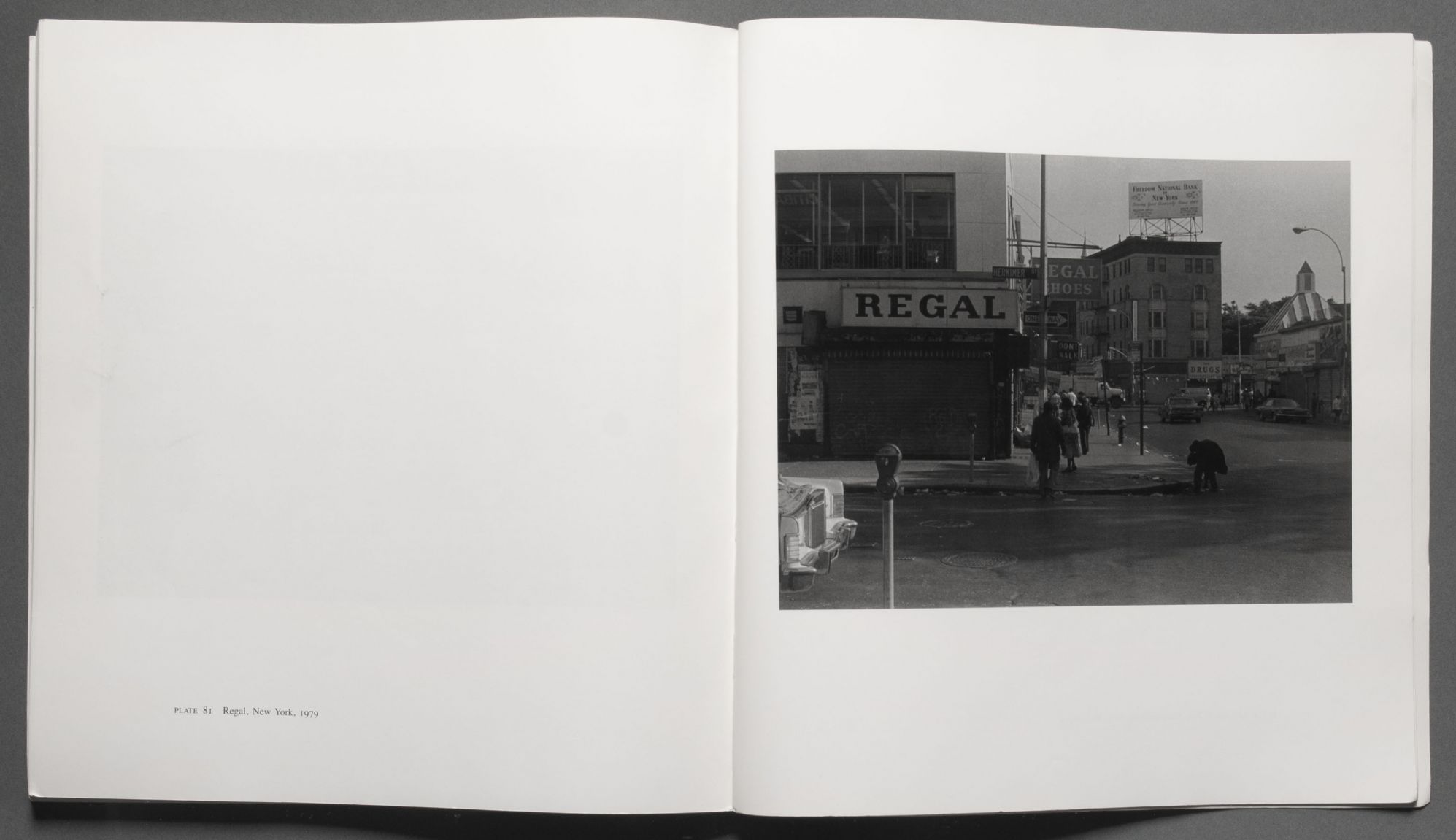

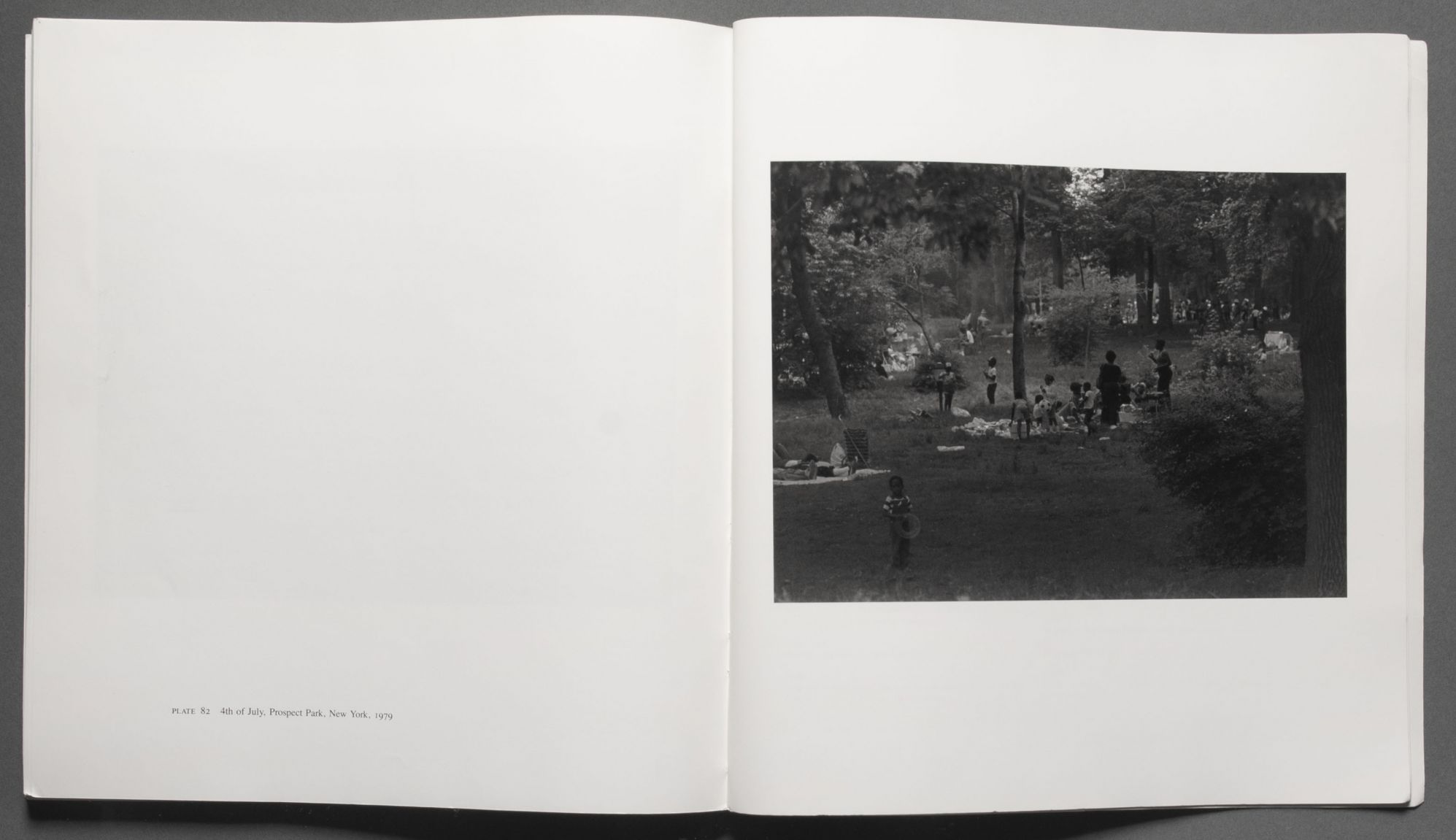

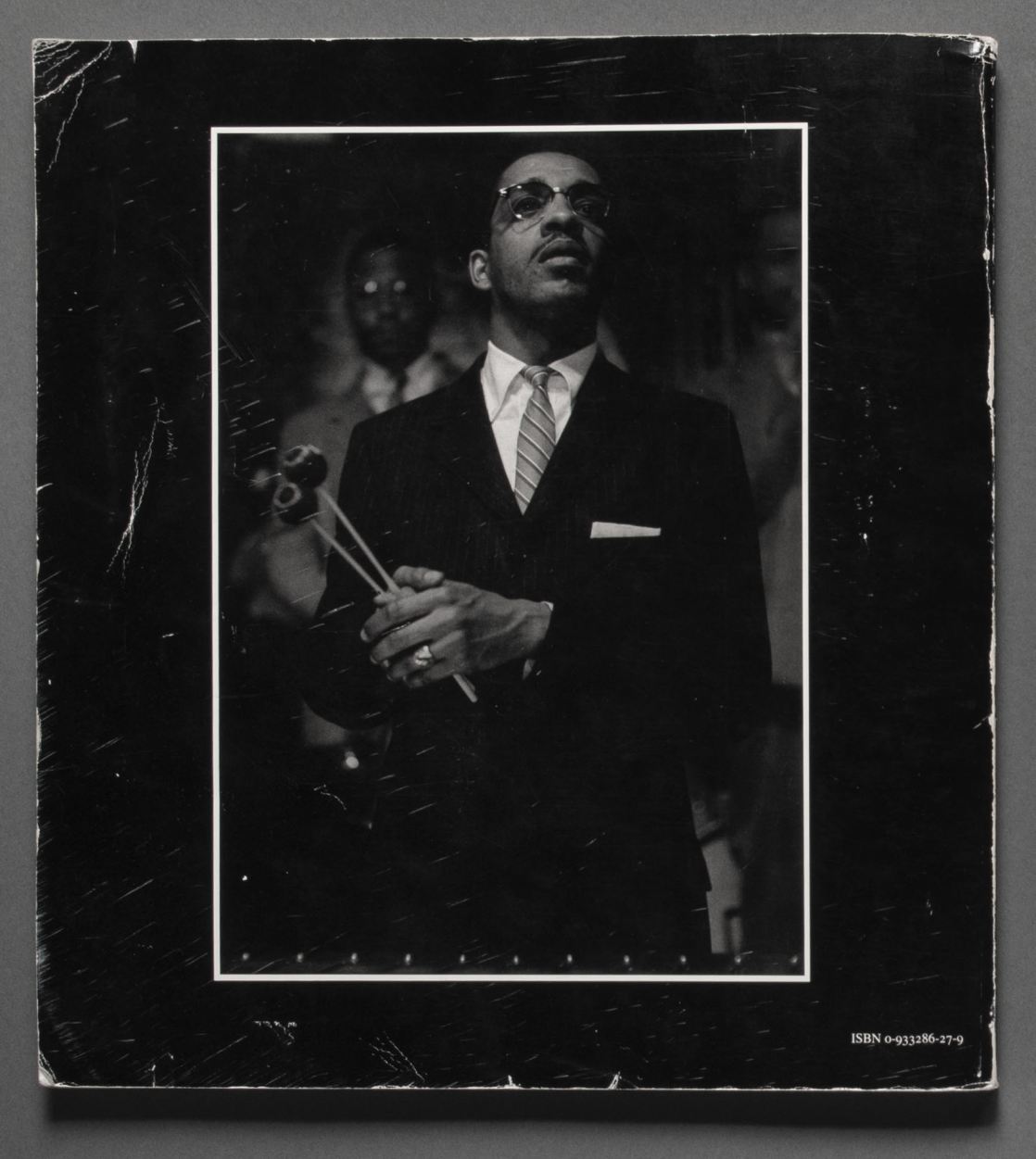

Ex-Libris: Roy DeCarava

Of the handful of photobooks I own about music, I can’t think of one that leaves me satisfied. I invariably wish I was listening to an album rather than looking at pictures. The most notable book on the subject I own is The Sound I Saw by Roy DeCarava. DeCarava is one of my favorite photographers and this is a book he designed himself in the 1960’s, but I still don’t love it. Even though only half of the 197 photographs are of musicians, it’s still too many for me. DeCarava’s lyrical texts and rhythmic design overemphasize jazz as the subject. The book is too loud – I can’t hear the music.

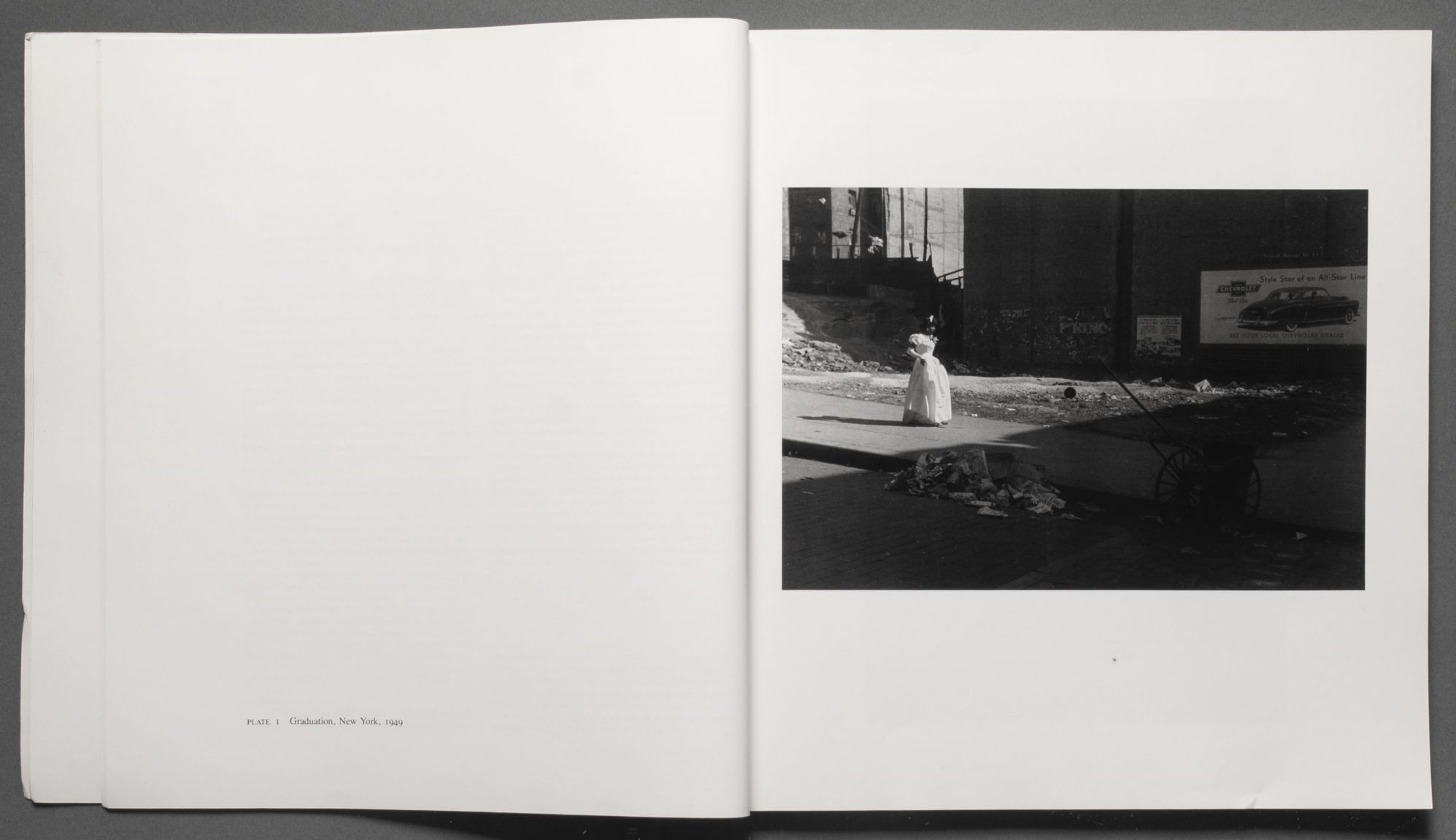

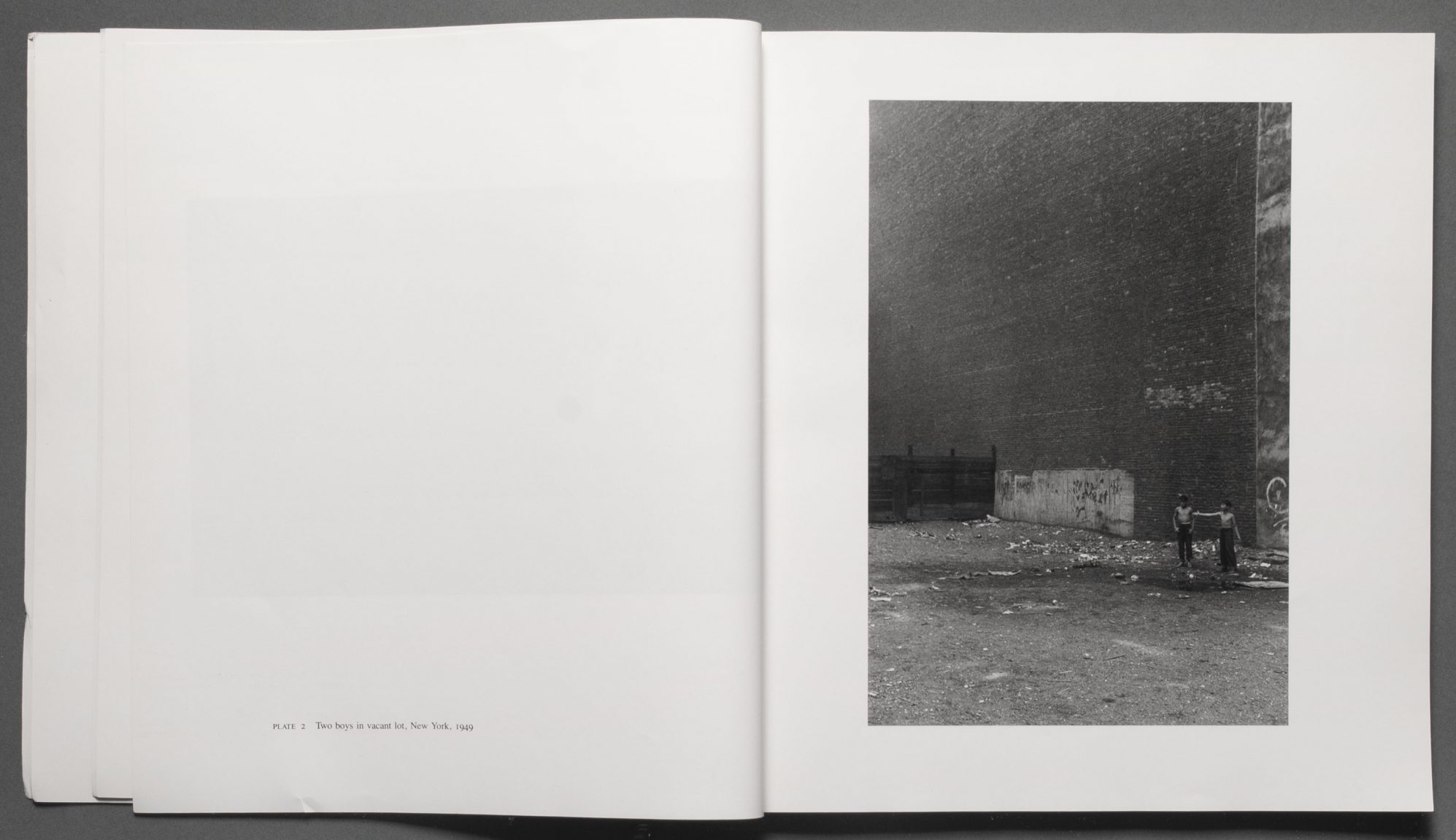

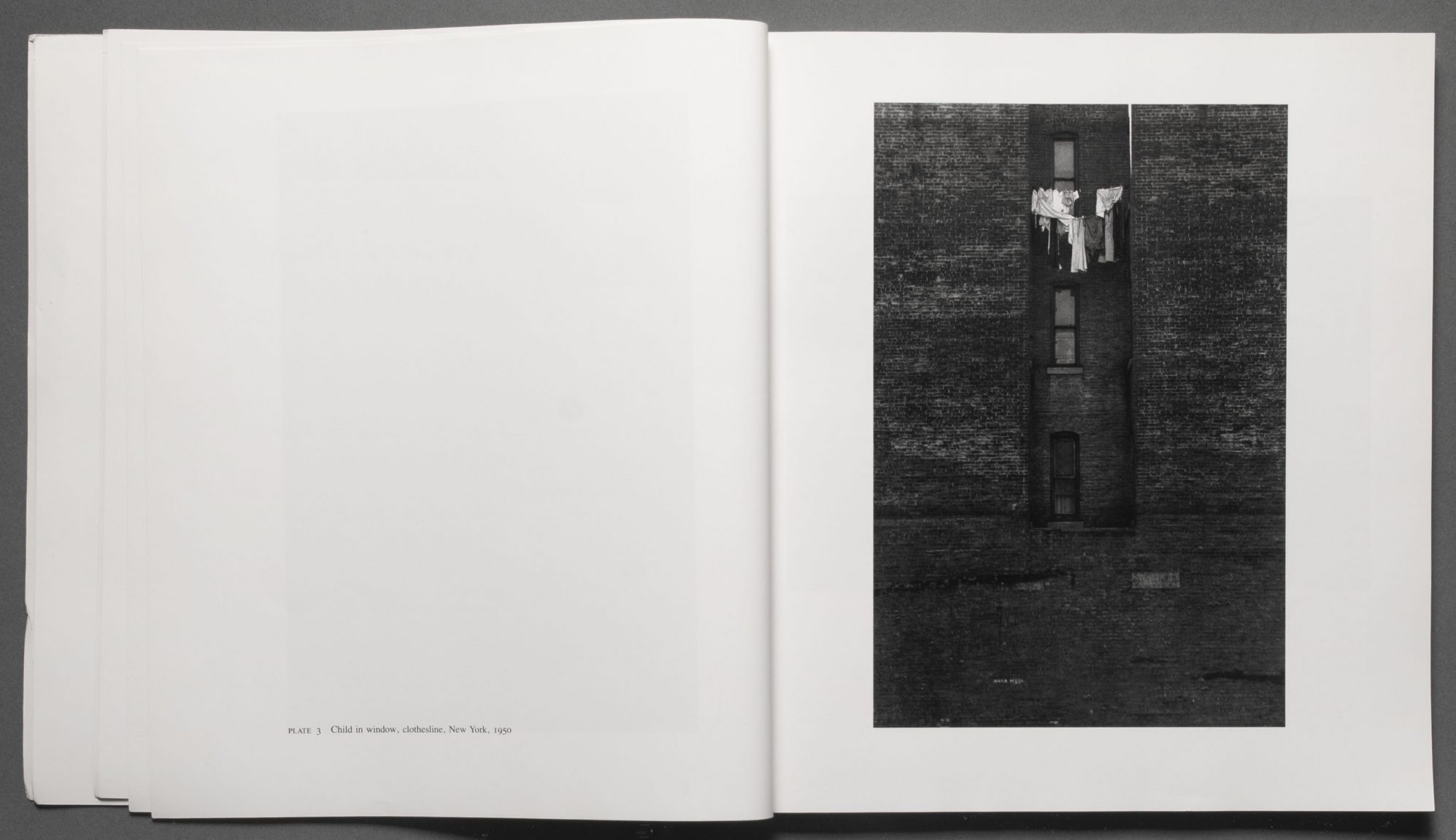

My favorite book by Roy DeCarava is a self-titled publication from 1981. It’s as understated as its title. There are only 82 plates, each presented on the right-hand page. The sequence is chronological with the first picture from 1949 and the last from 1979. In an email exchange I had with the book’s editor, James Alinder, he made the process of putting it together sound straightforward:

“When I was a photo prof at the University of Nebraska, I did an exhibition and small book on Roy and had him come as a visiting artist at the Sheldon Gallery. He stayed with us, slept on his back so his face wouldn’t wrinkle. He had never sold his prints, and we offered them in the gift shop for $25 each. And we became friends. Fast forward a decade or so, and as the executive director of the Friends of Photography, I had the opportunity to do a real book on Roy. As I remember, we did the selection and sequencing together along with David Featherstone. It was a membership bonus publication so we sent out more than 10,000 copies to our members.”

I confess I was a bit disappointed by Alinder’s response. Roy DeCarava is one of my all-time favorite books. I’ve often thought that if it had a fancy editor and a sexier title, it would be considered one of the great American photobooks. Either way, I still think it is one of the most soulful books ever published. You can feel the music through DeCarava’s muted restraint. He describes this quality eloquently in the book’s introduction:

“It’s like the pole vaulter who begins his run, shoots up, then comes down. At the peak there is no movement. He’s neither going up nor going down. It is that moment that I wait for, when he comes into an equilibrium with all the other life forces …The moment when all the forces fuse, when all is in equilibrium…that’s jazz…and that’s life.”

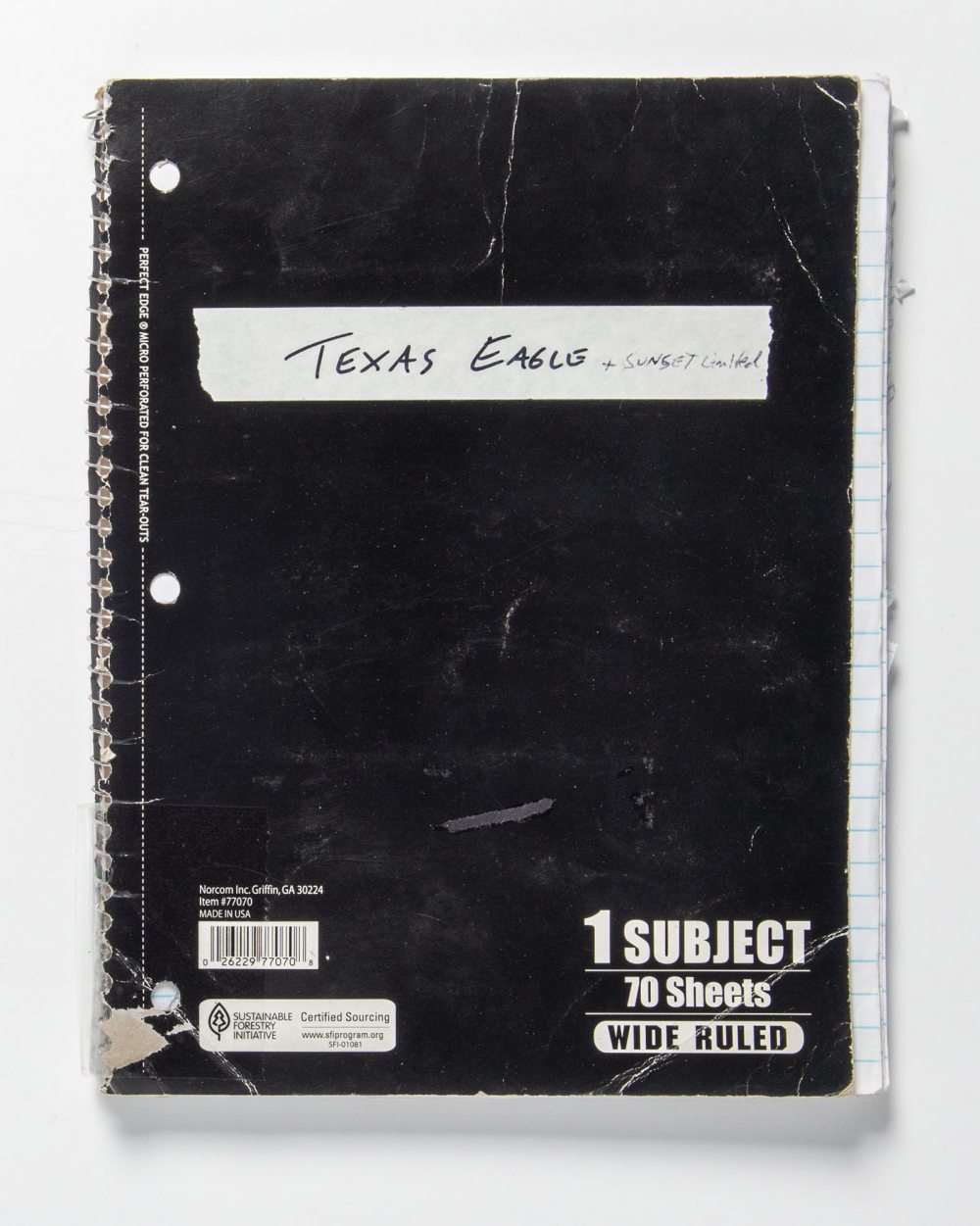

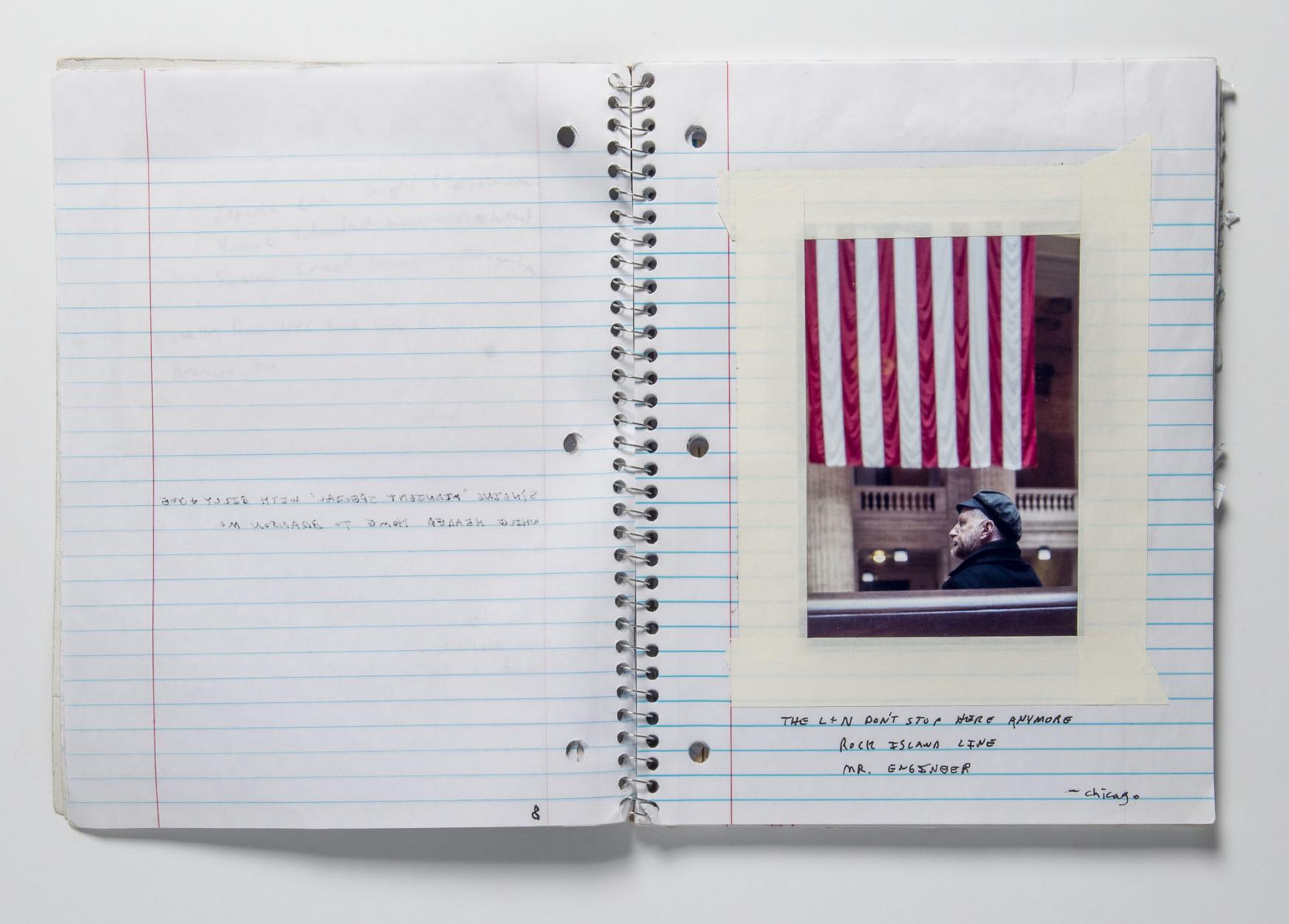

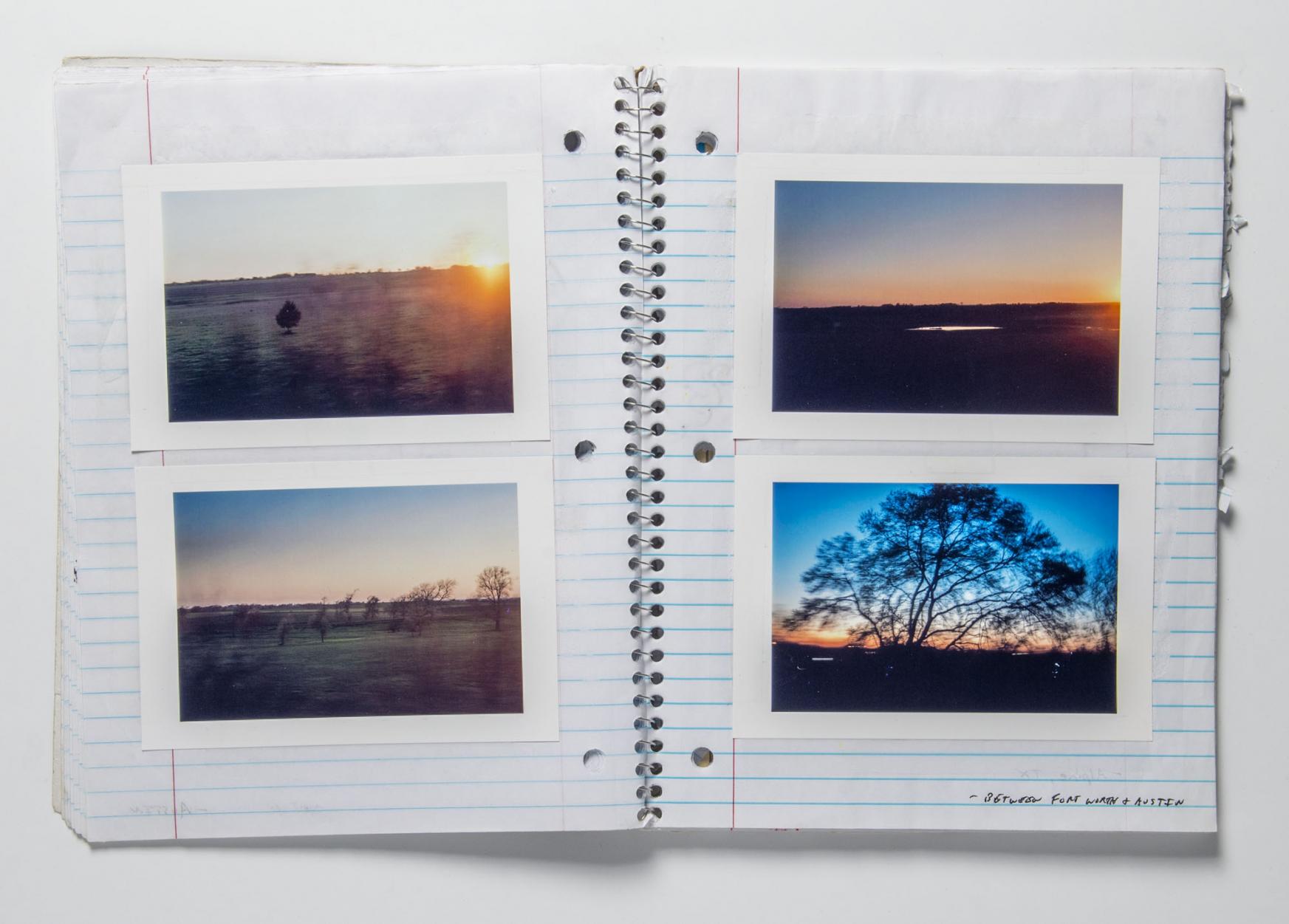

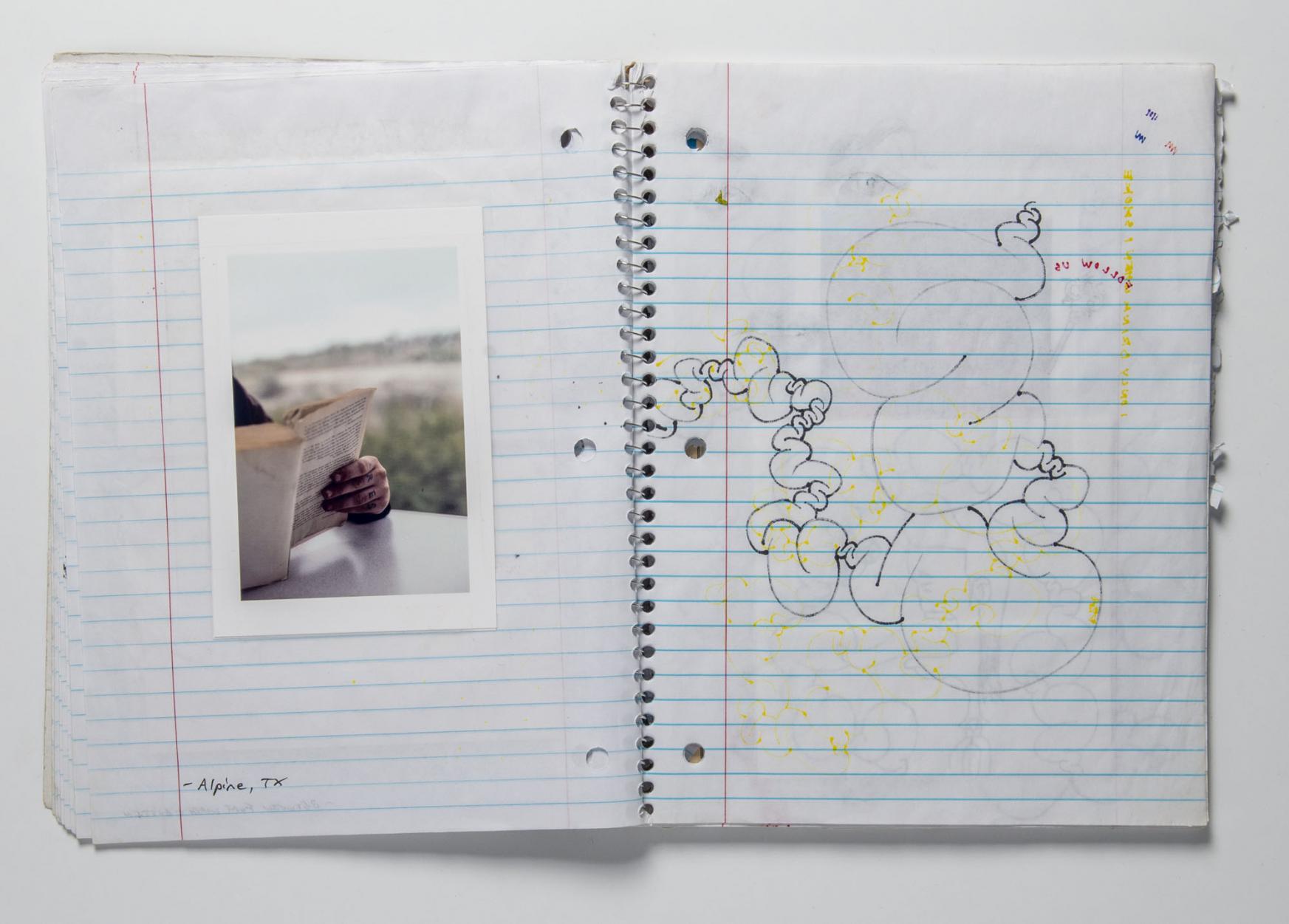

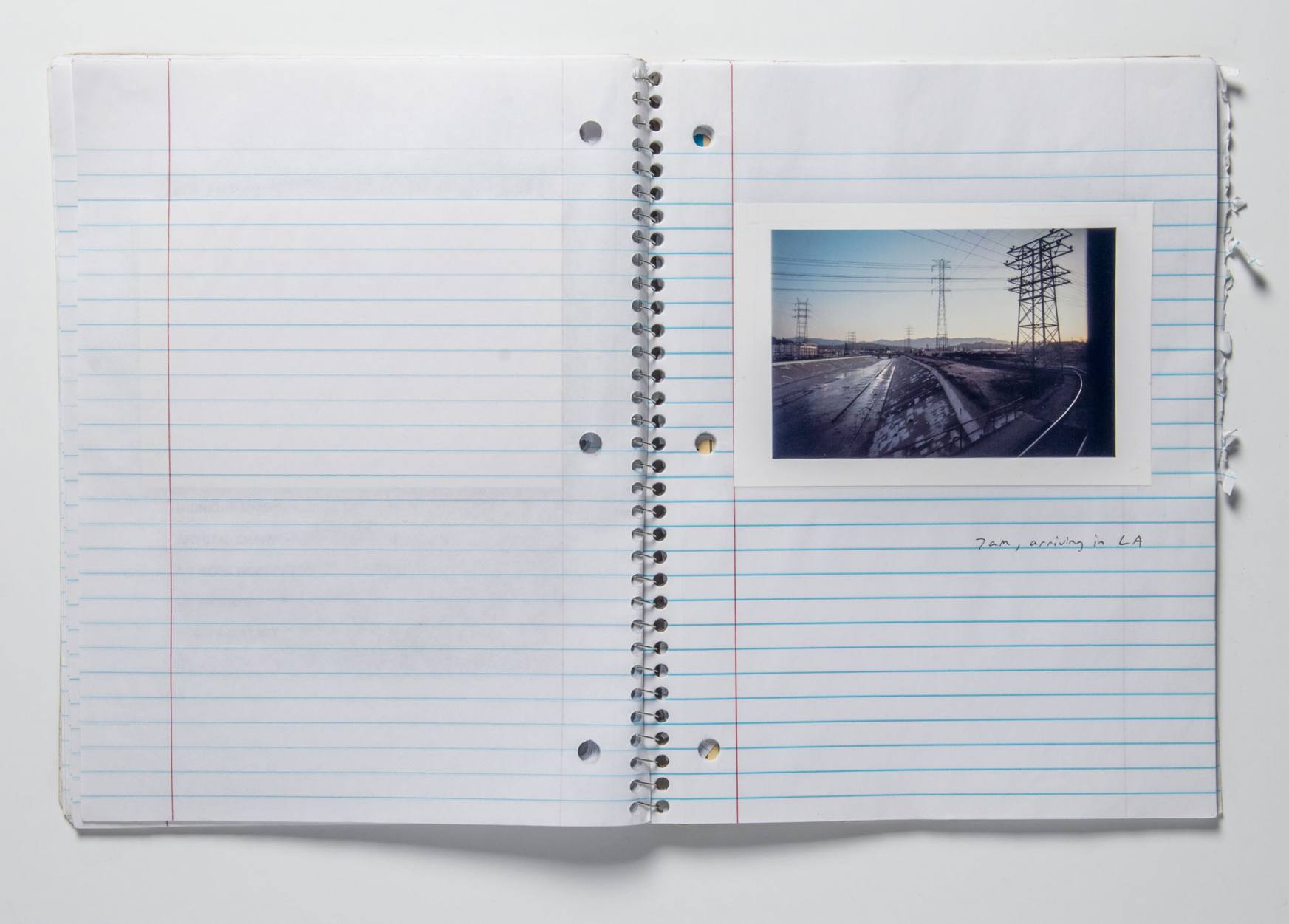

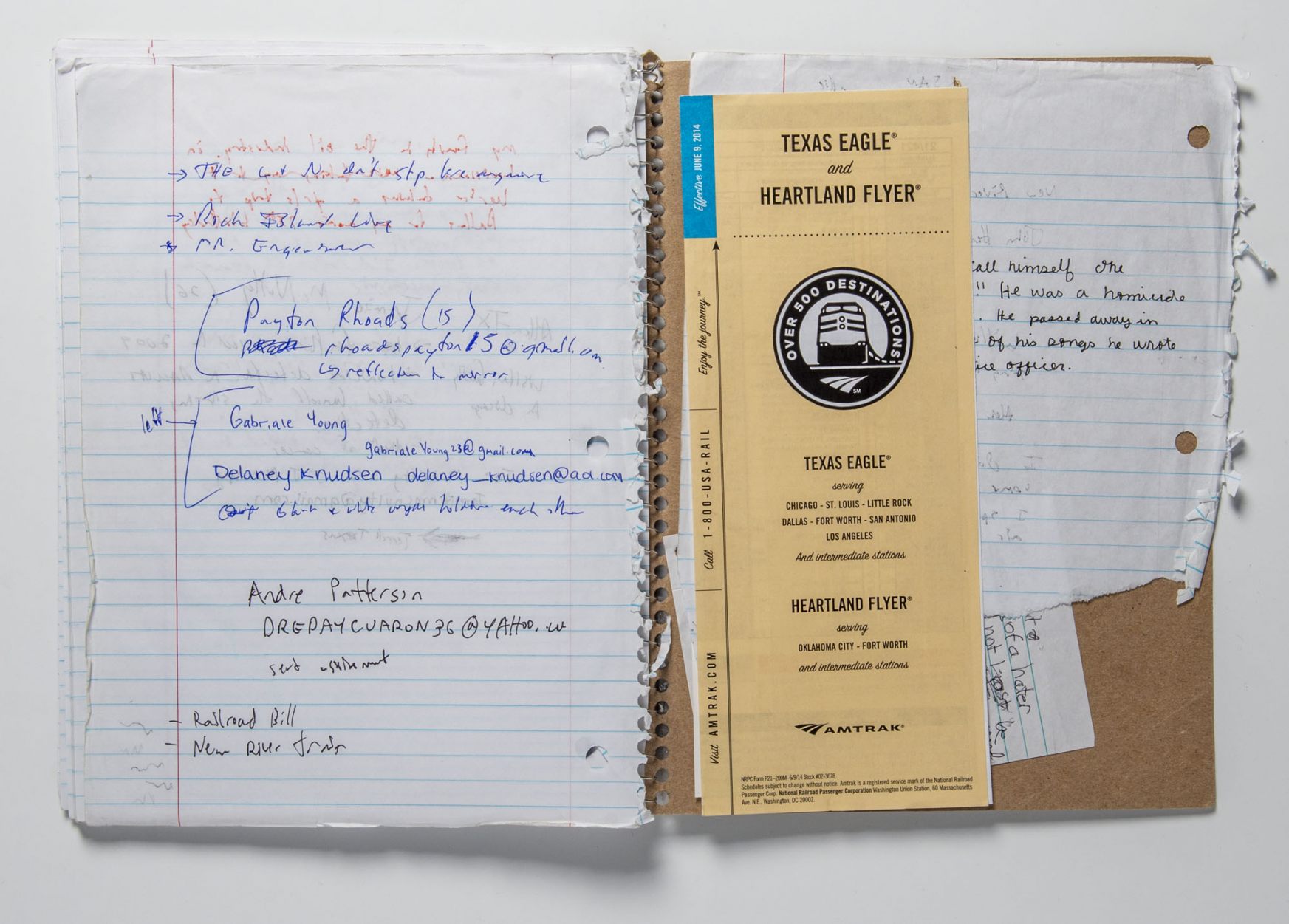

Archive Dive: Texas Eagle

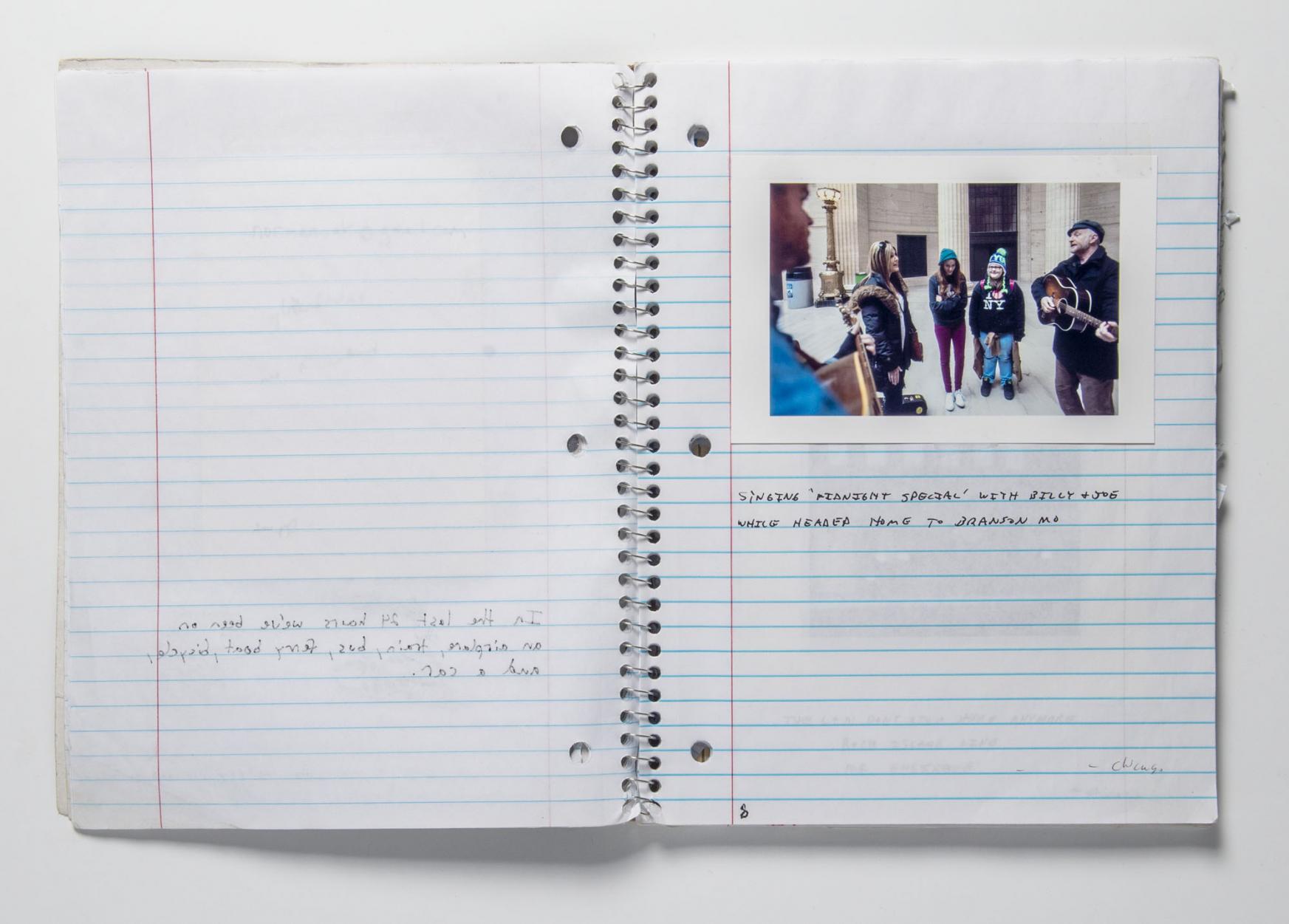

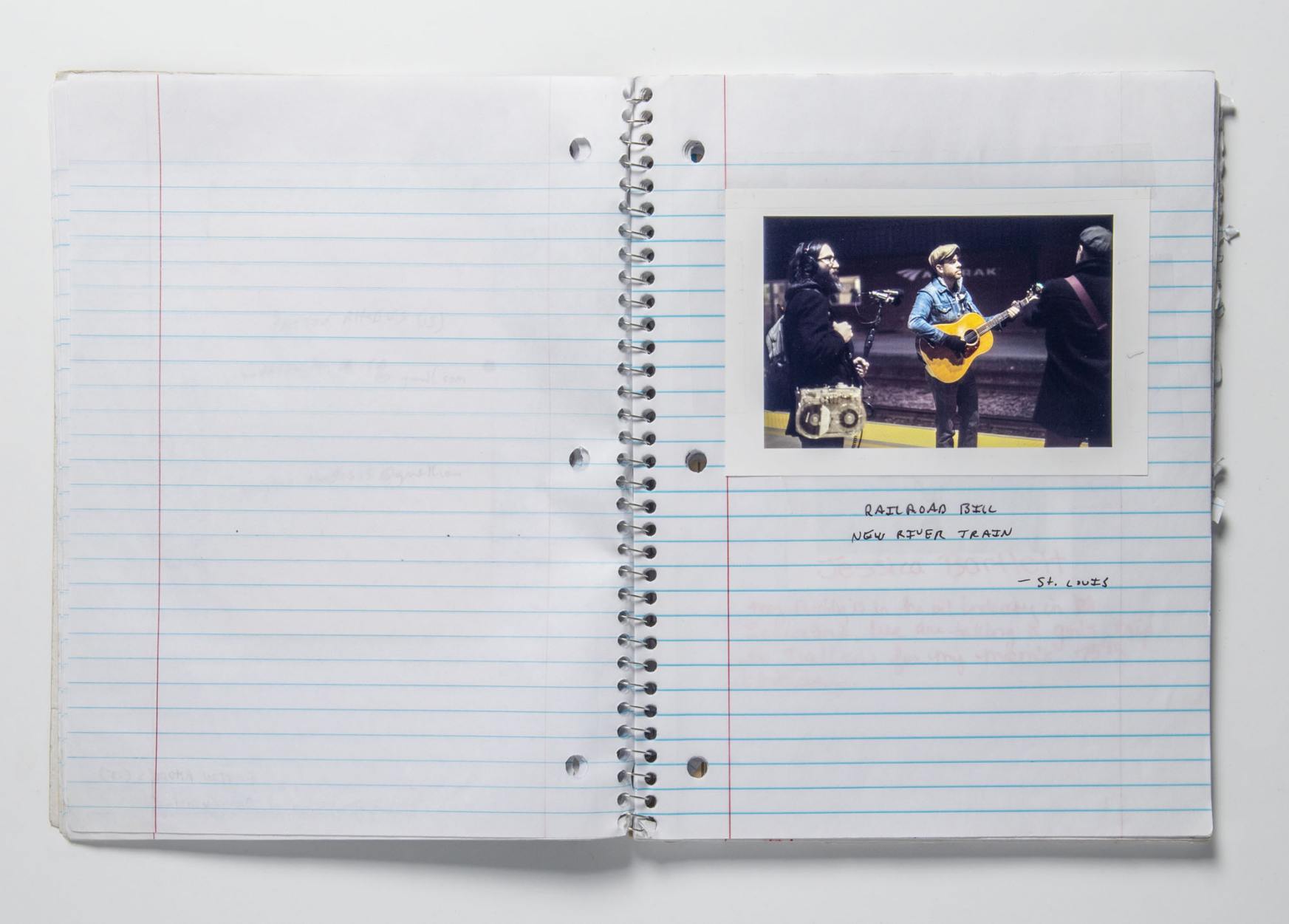

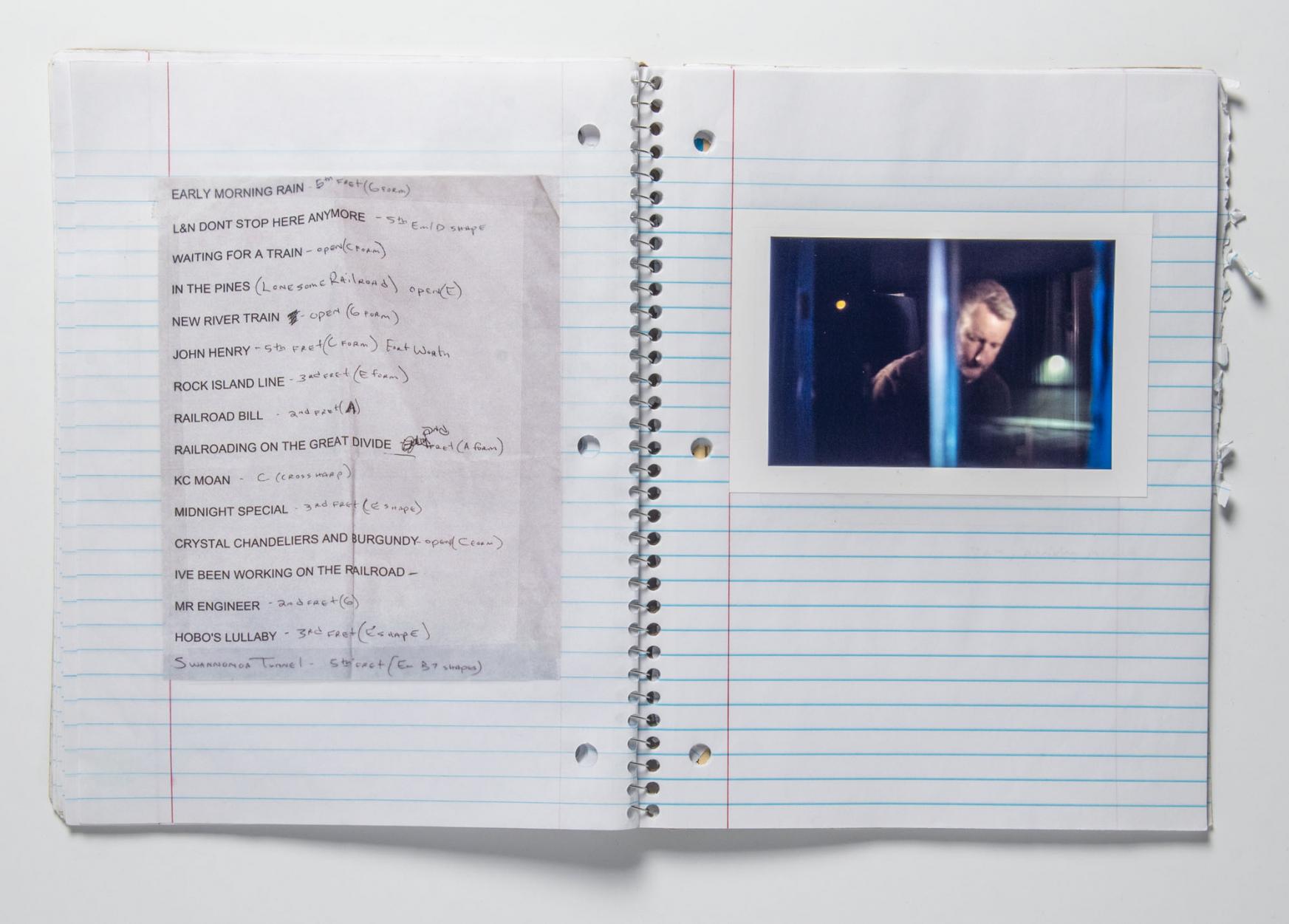

In a recent online tour of my library, I briefly showed an old notebook. For this musical edition of the newsletter, I thought I’d offer a closer look. In 2014, Aperture approached me asking if I could create a live event for a fundraiser thematically tied to their book, The Open Road. I ended up approaching the singer-songwriter Billy Bragg, who I knew had a fascination with Woodie Guthrie and the mythology of the American road. When I talked to Billy, he immediately suggested doing something related to the folk song “Rock Island Line.”

In August of 2014, I drove my Honda Odyssey to Chicago to meet Billy and the musician Joe Purdy. Accompanying us was my filmmaker friend Isaac Gale. The four of us drove from Rock Island, Illinois to a prison in Arkansas where the song was first recorded by Alan Lomax in 1934. (You can read an old story about this project by none other than Rebecca Bengal.) The next month we did a live performance in New York with songs, photos, videos and storytelling.

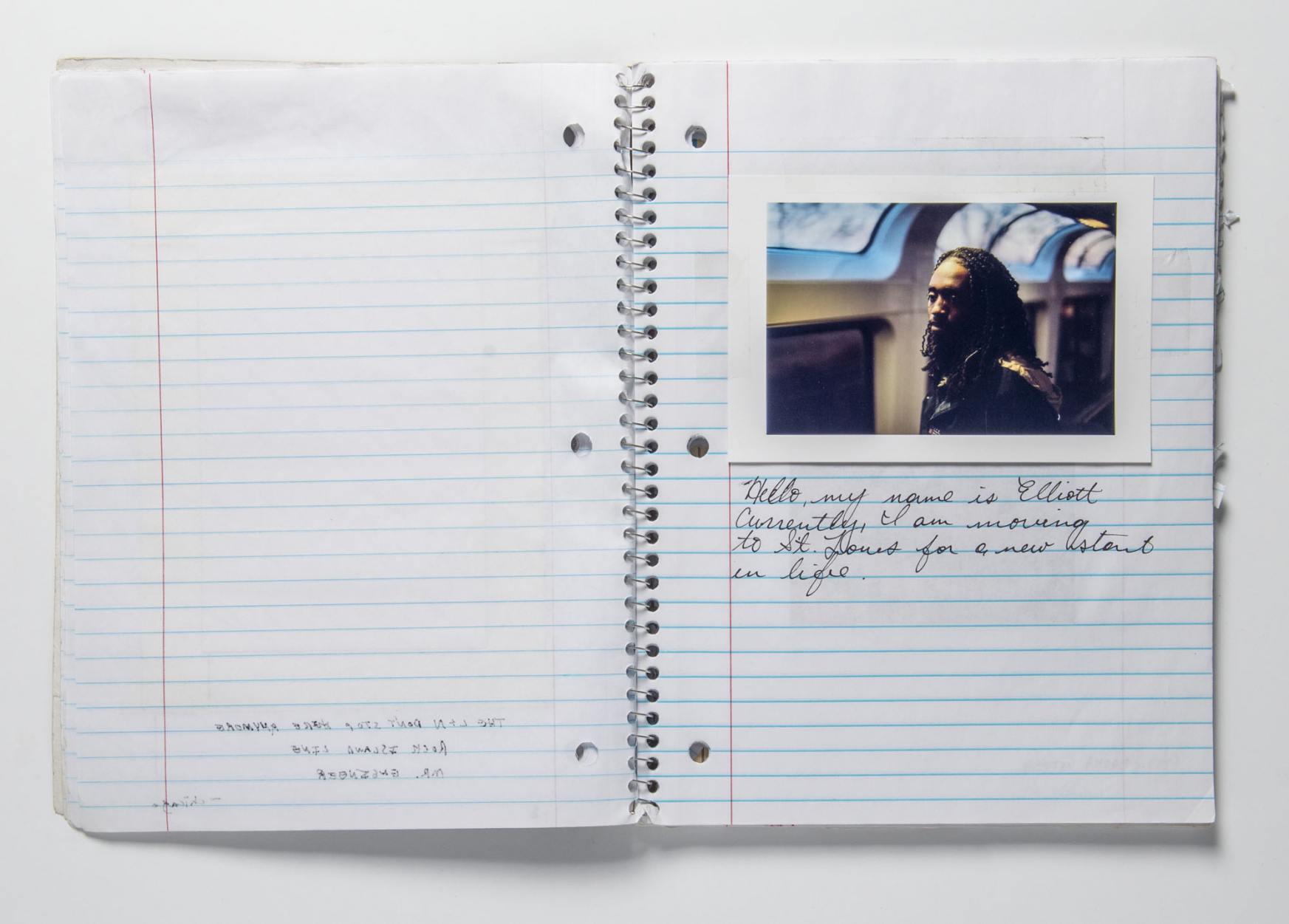

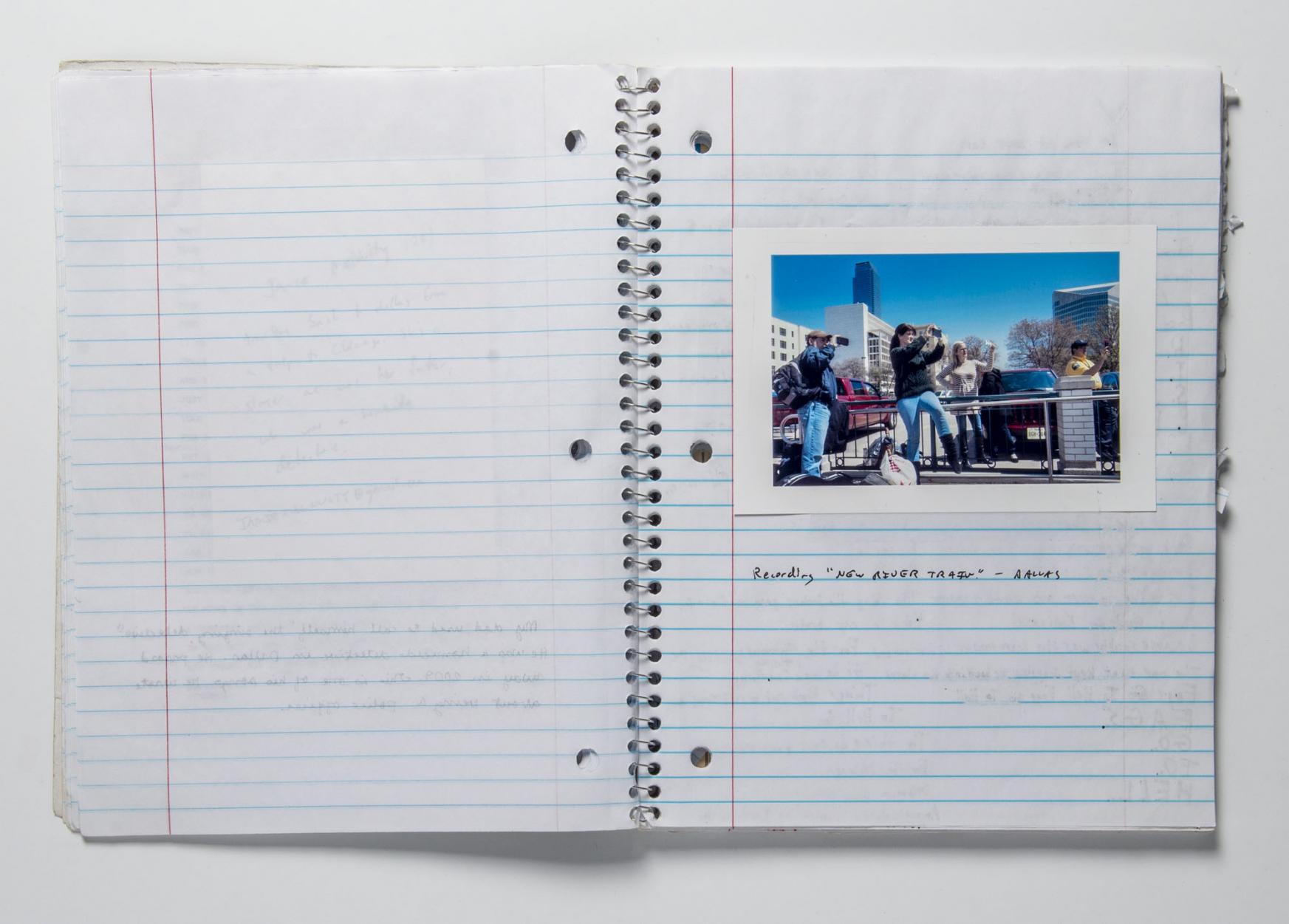

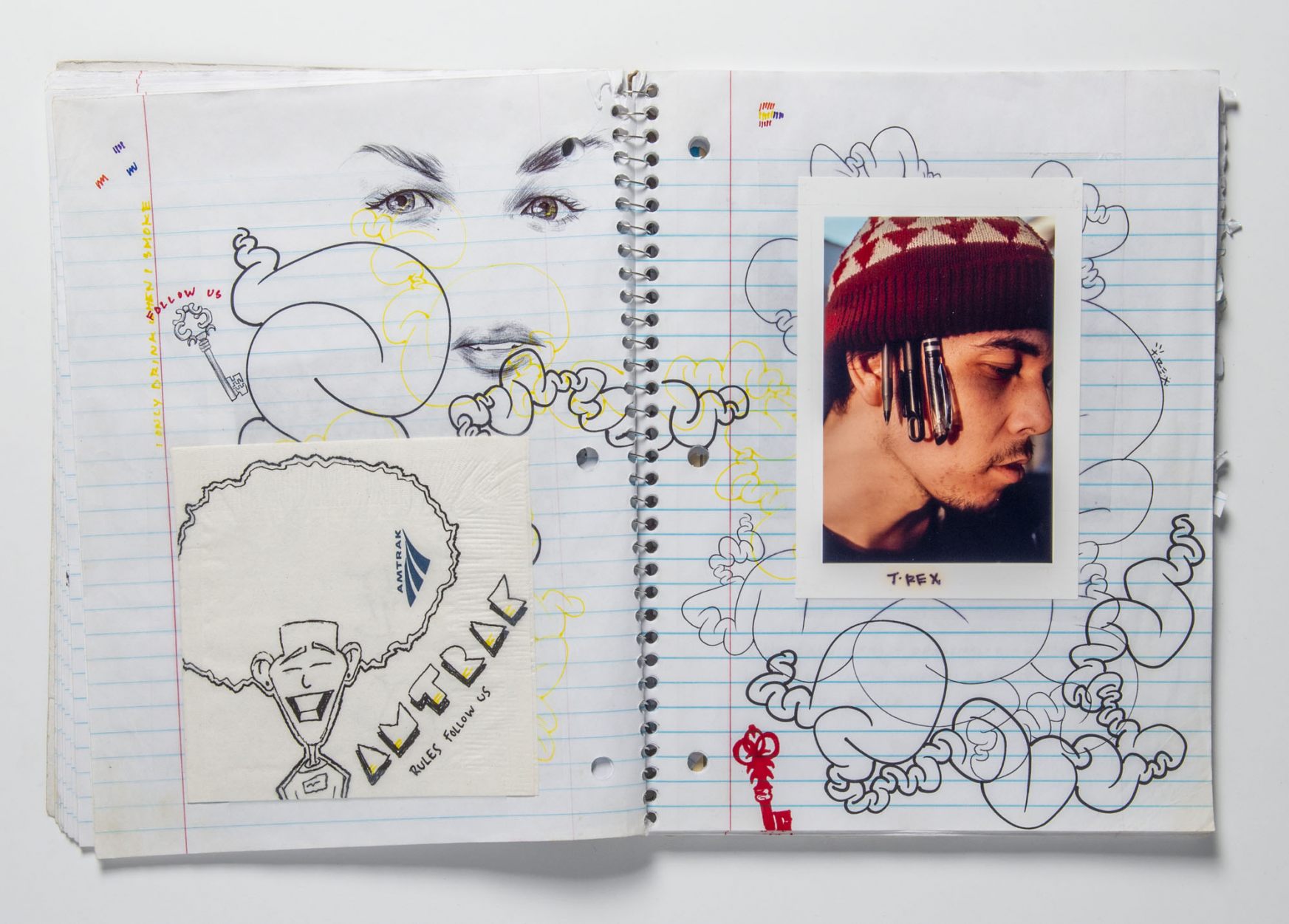

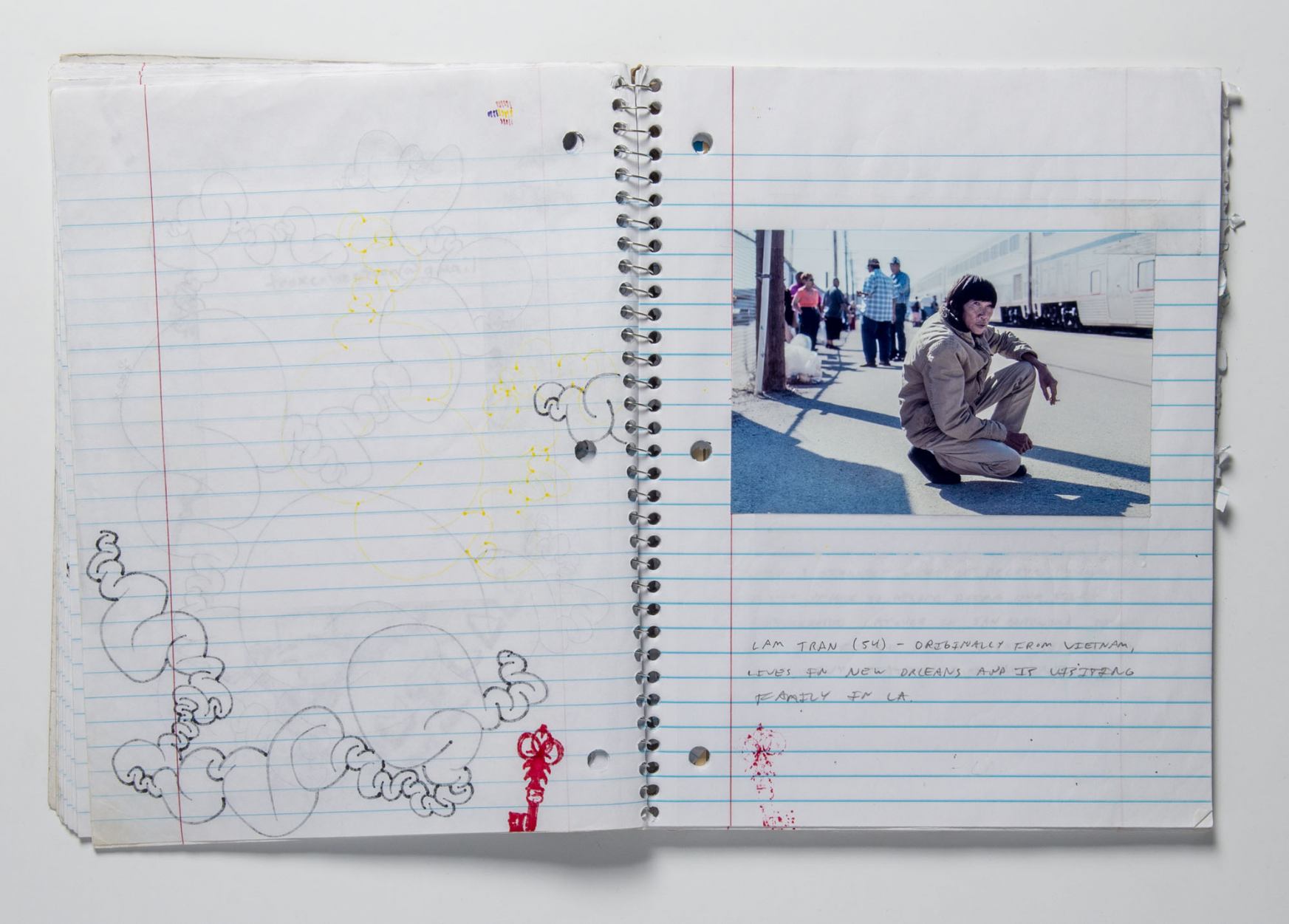

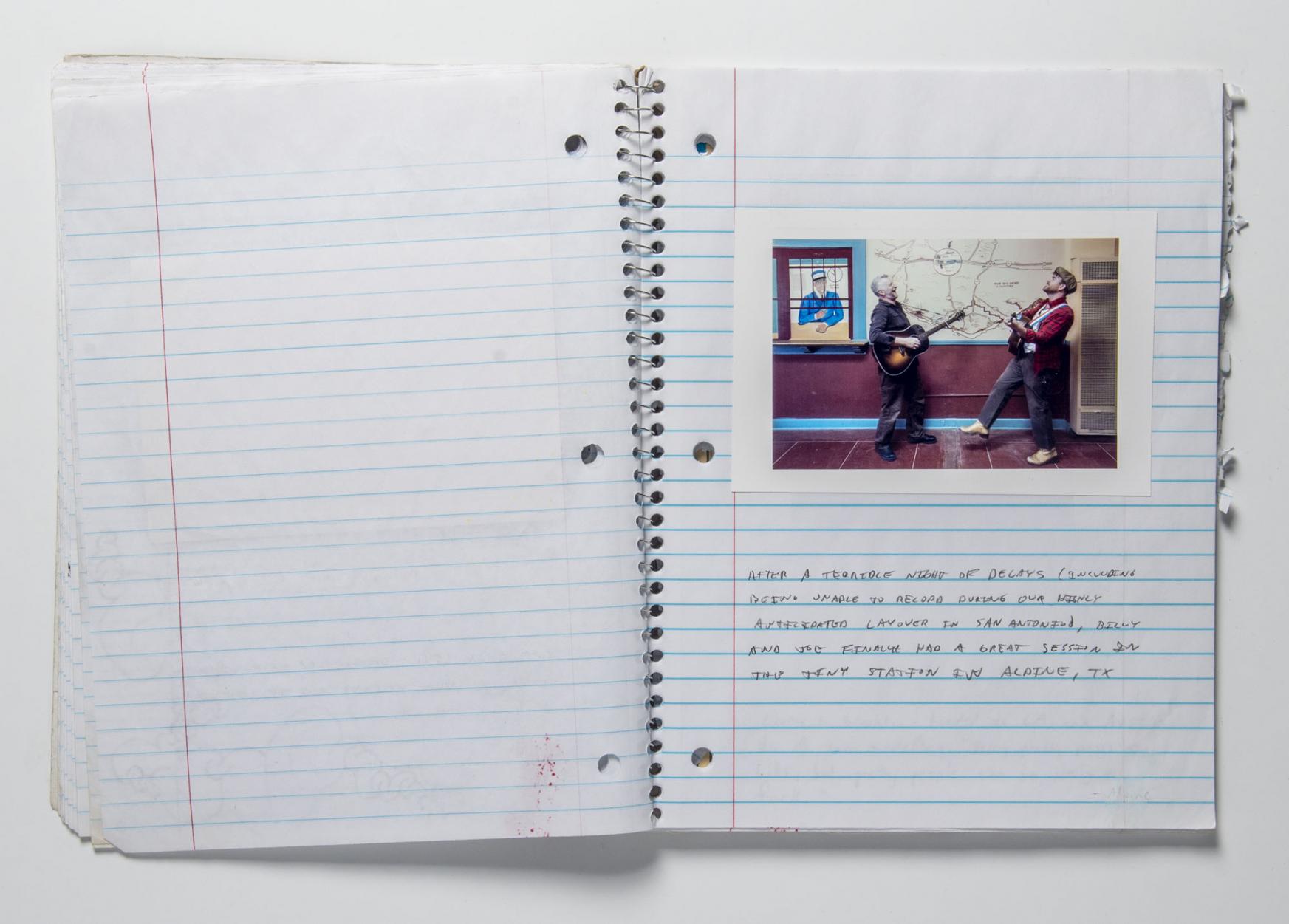

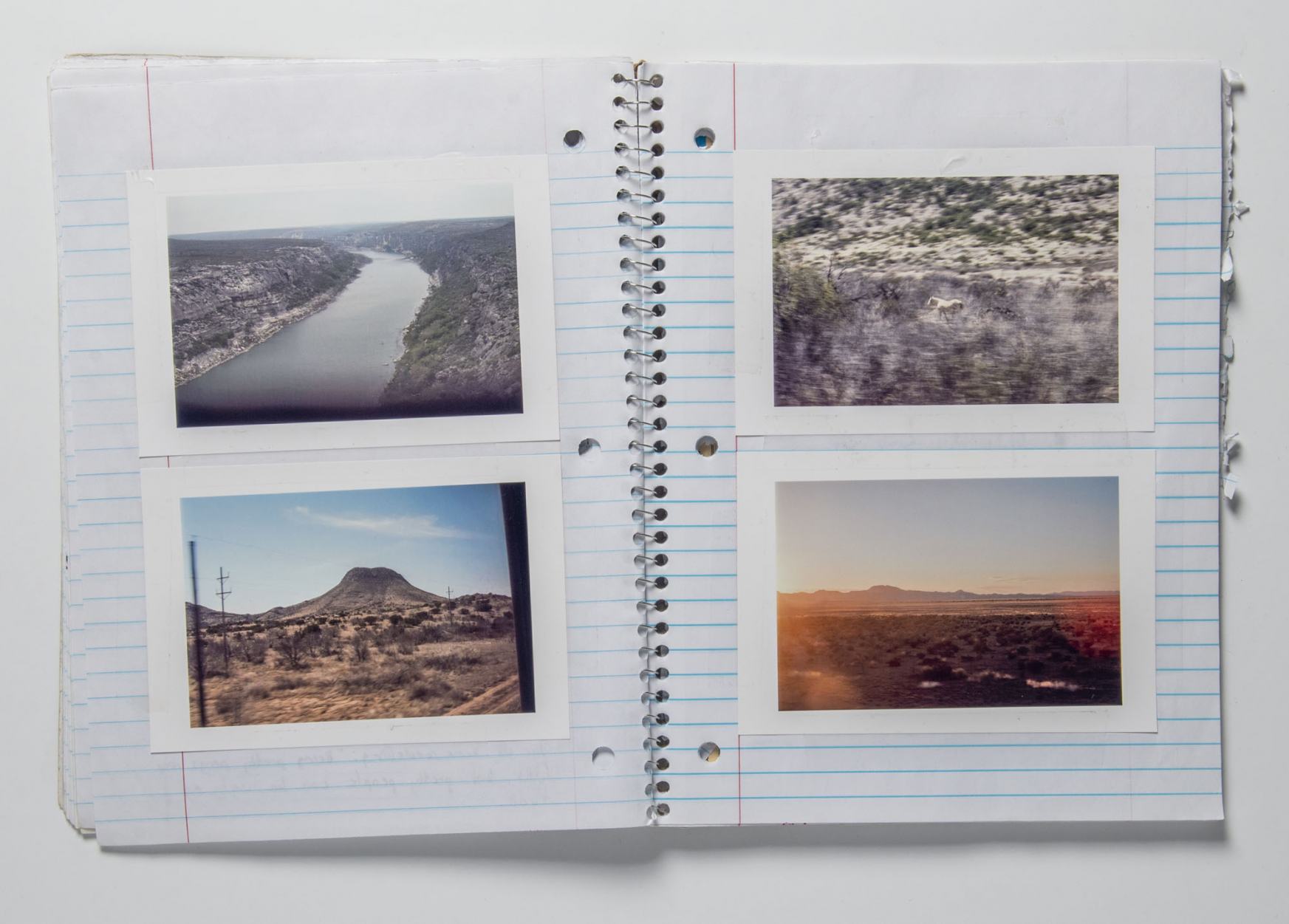

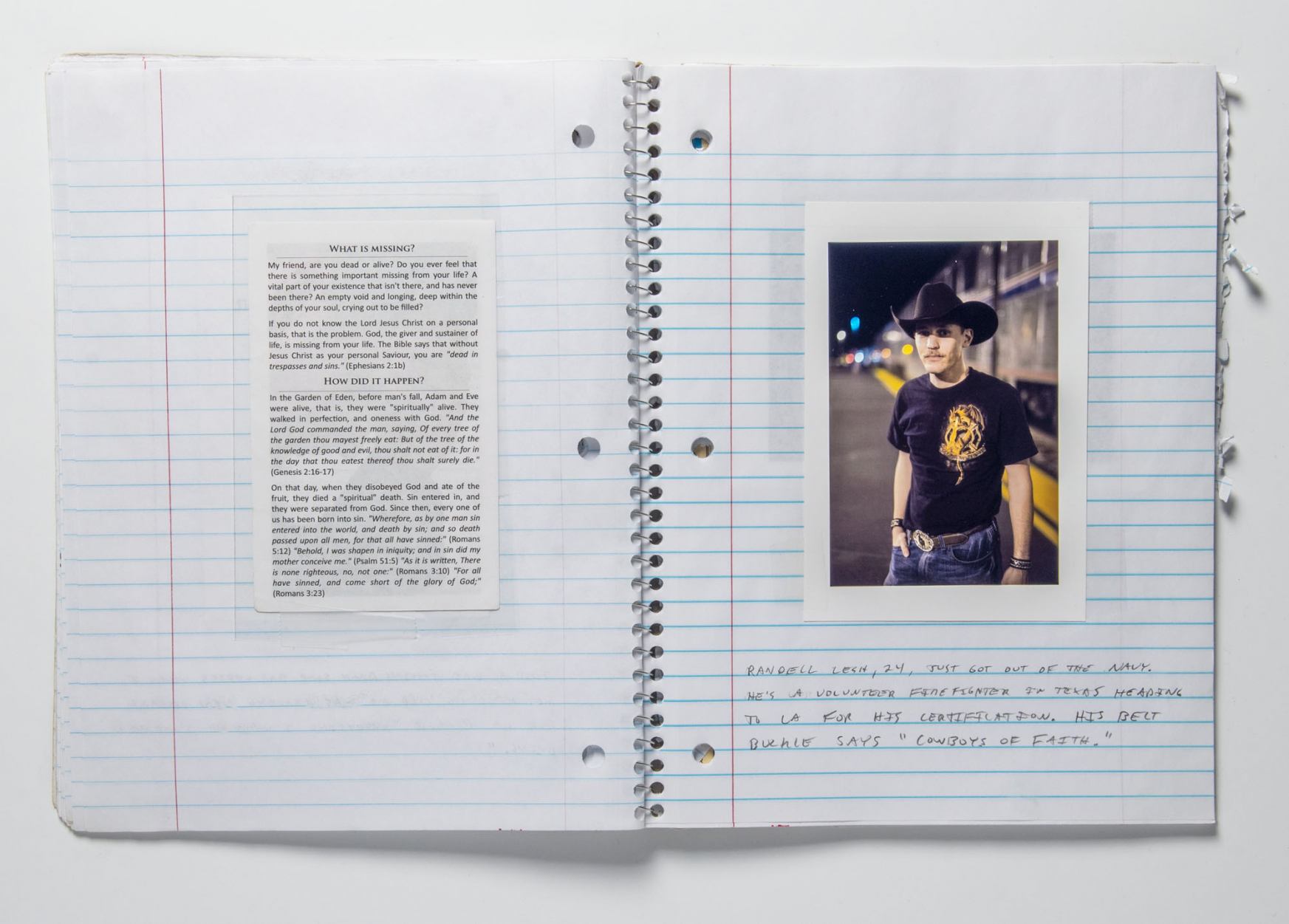

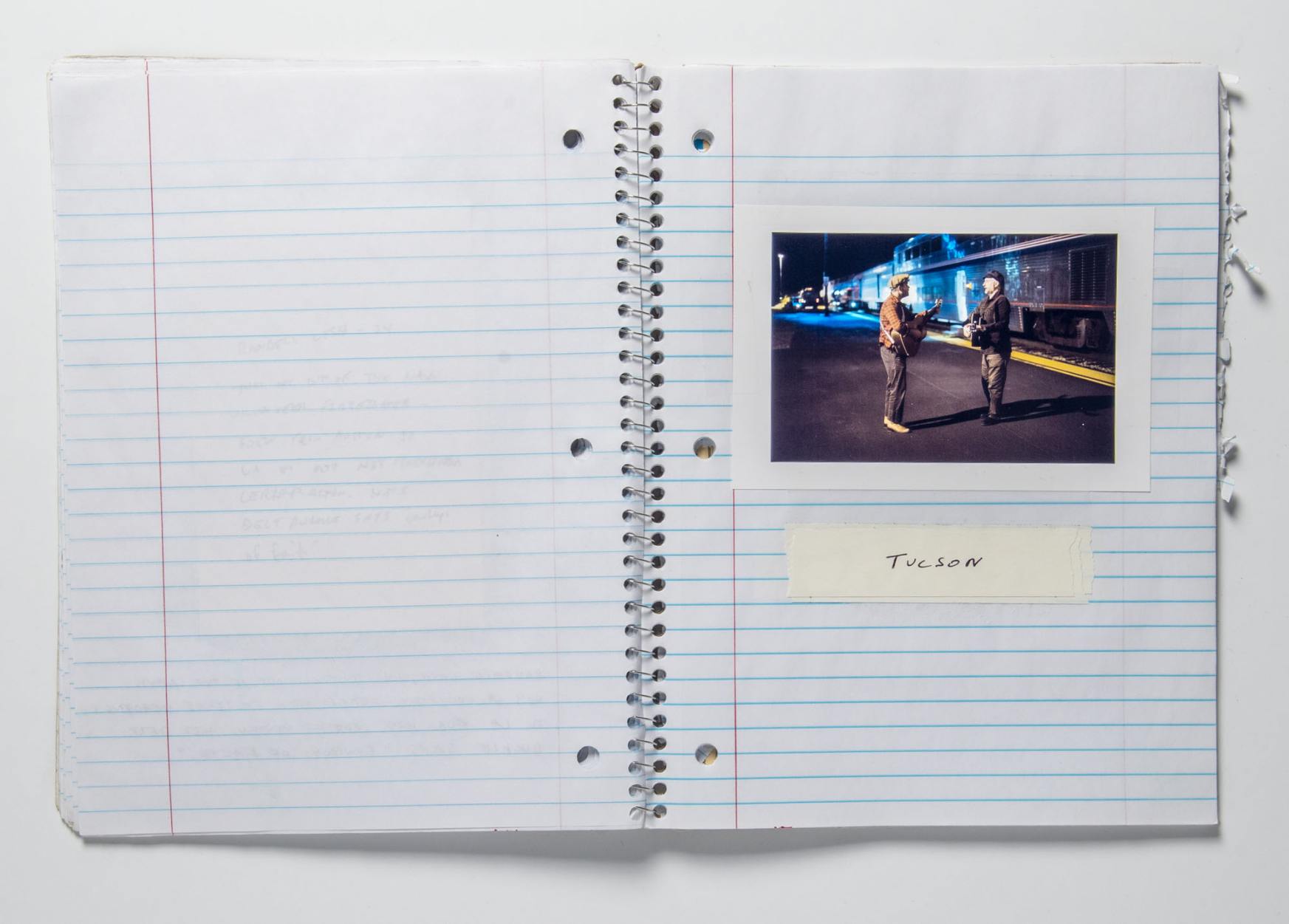

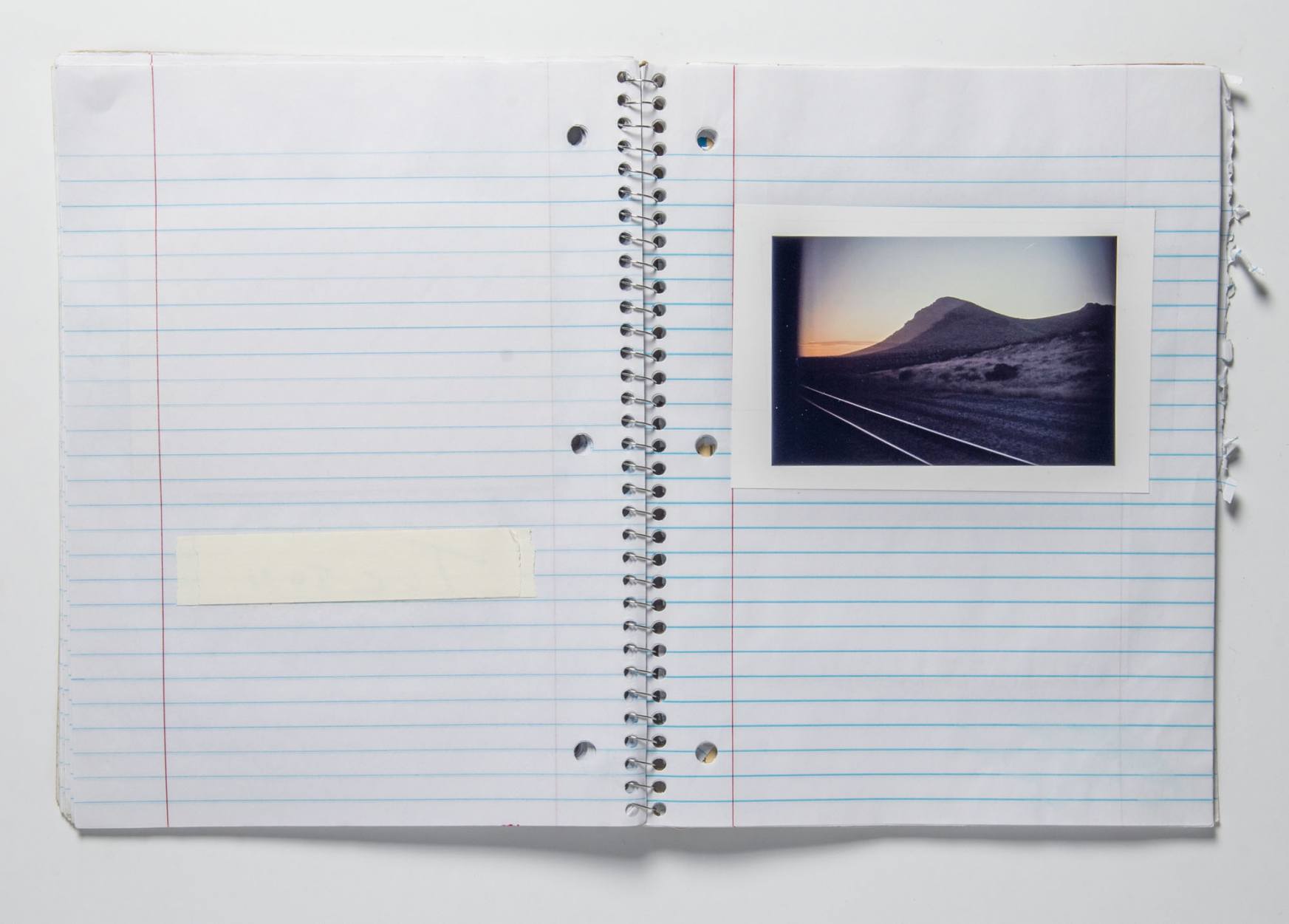

In 2015, Billy called me saying he wanted to make another trip, but this time on a train. His idea was to produce an album by recording songs on reel-to-reel tape at every stop. Once again Billy, Isaac and I met in Chicago, but this time our route went down to Texas and across the Southwest to Los Angeles. Billy and I shared a sleeper car and he insisted I take the upper bunk.

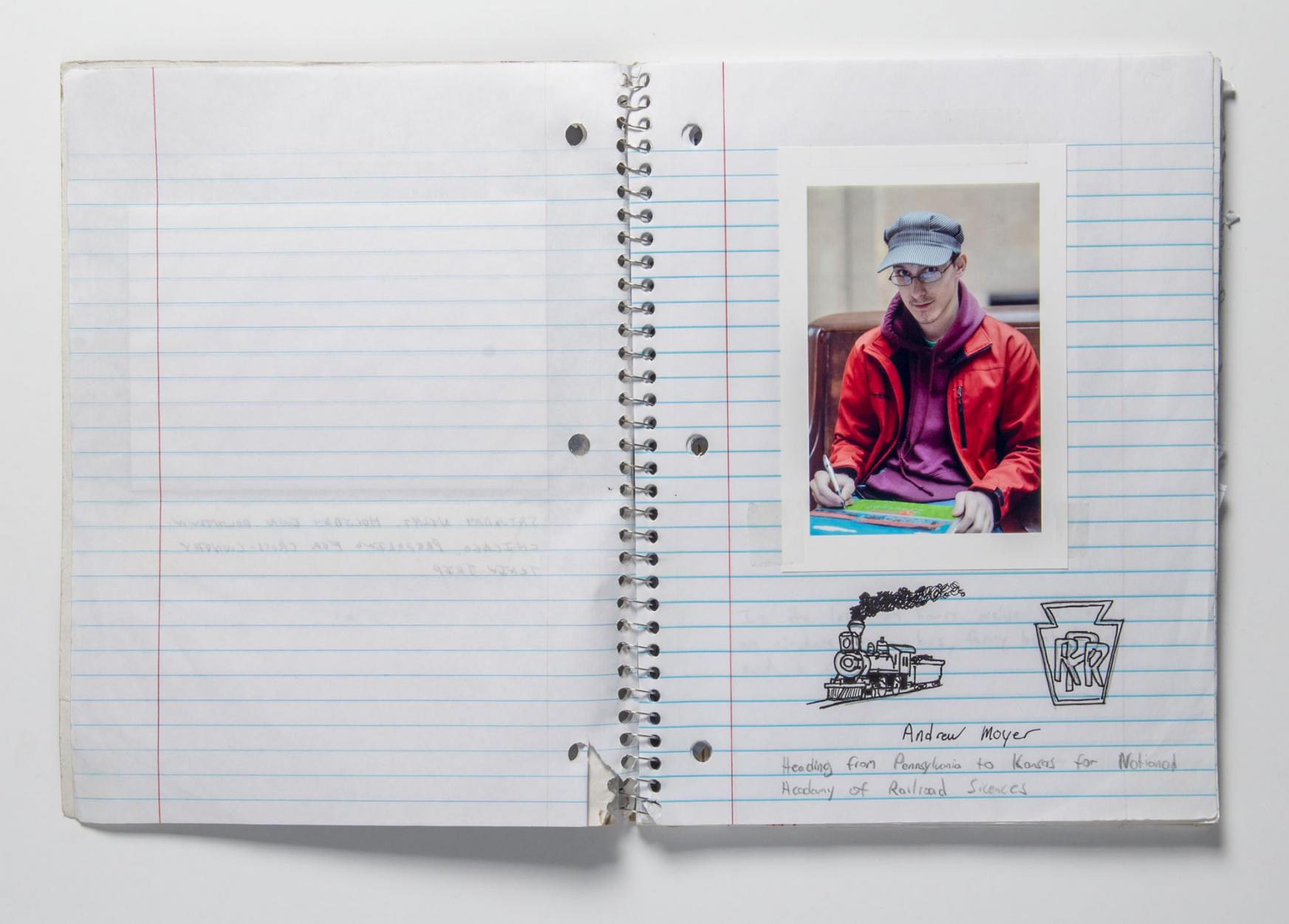

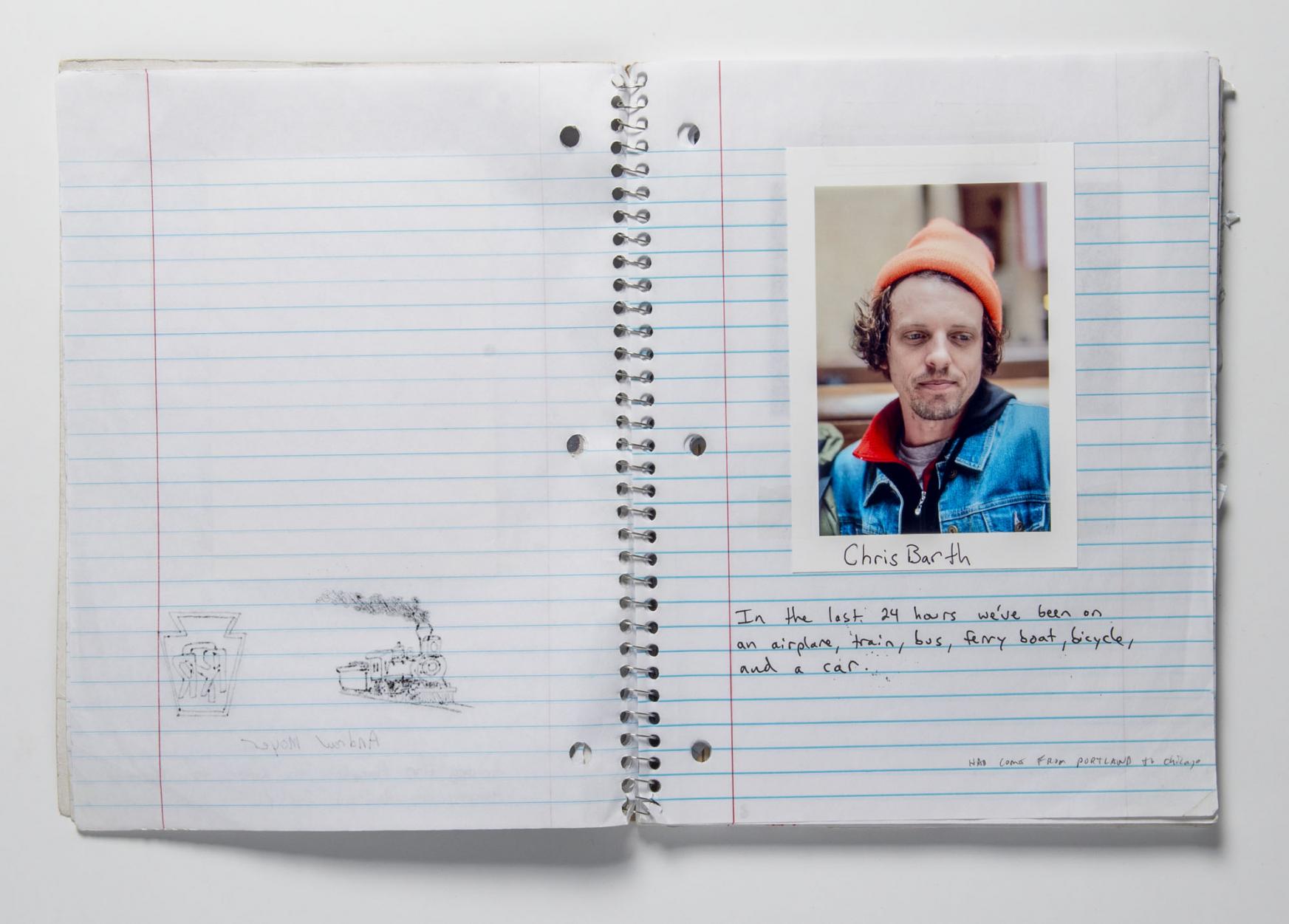

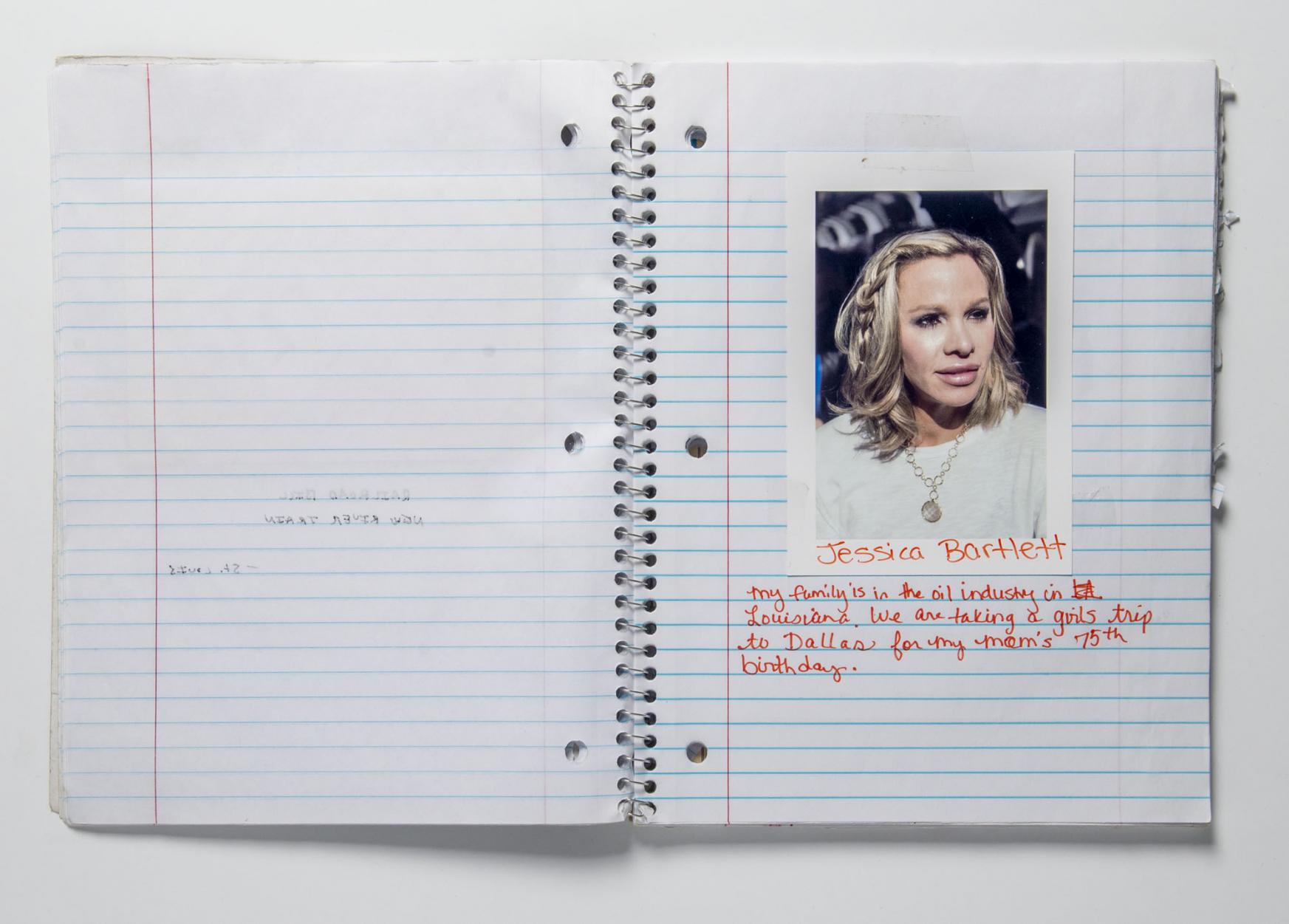

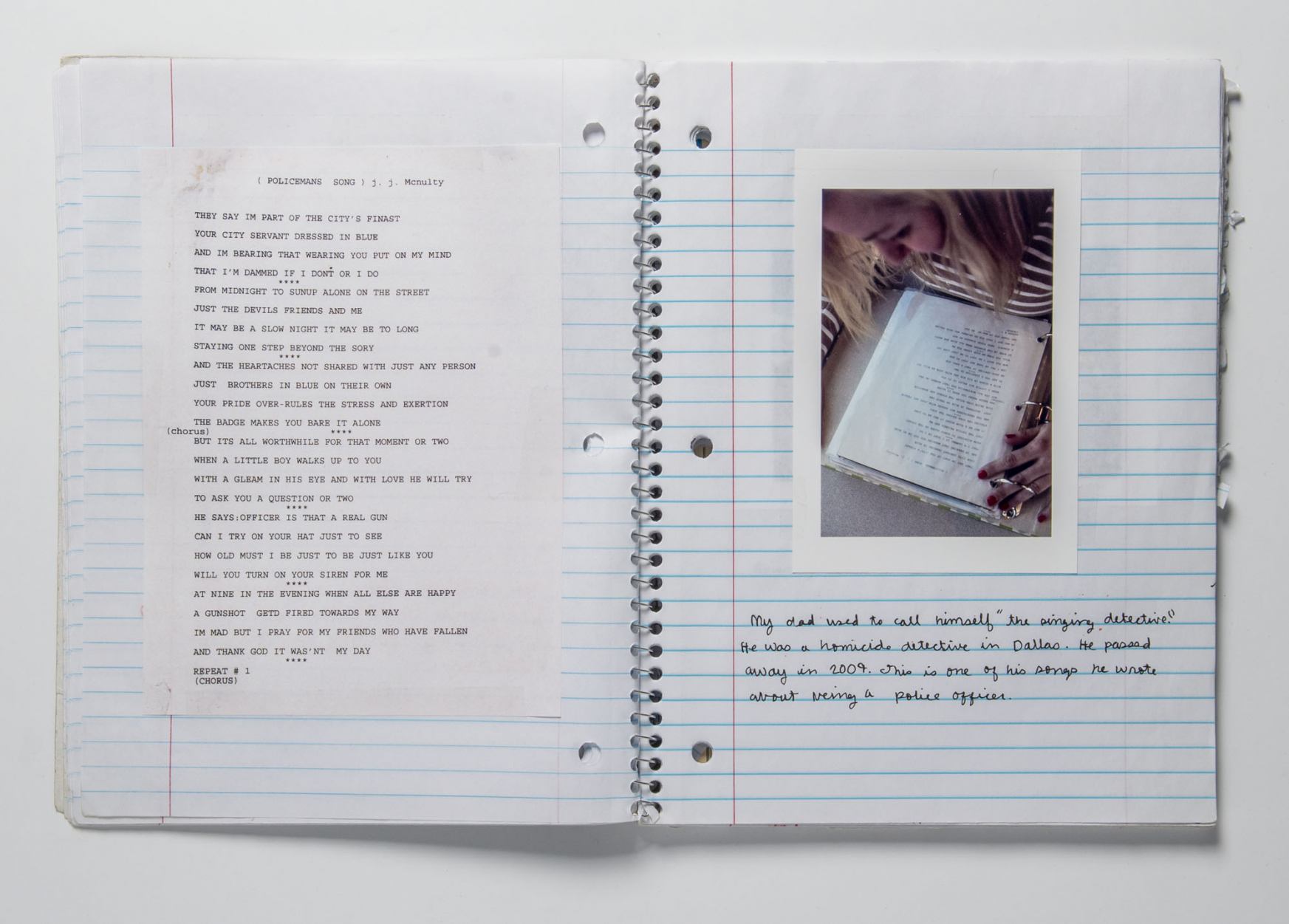

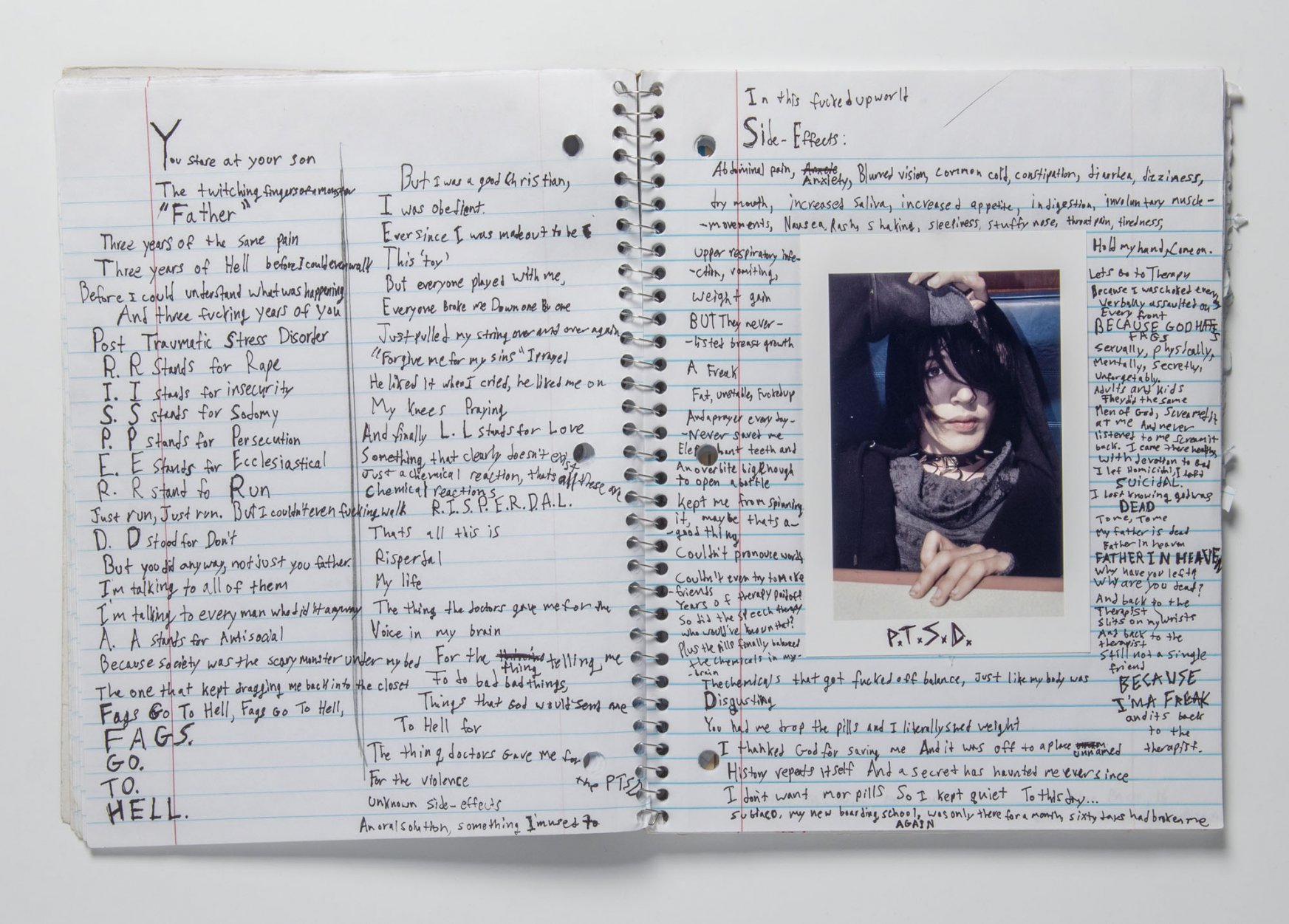

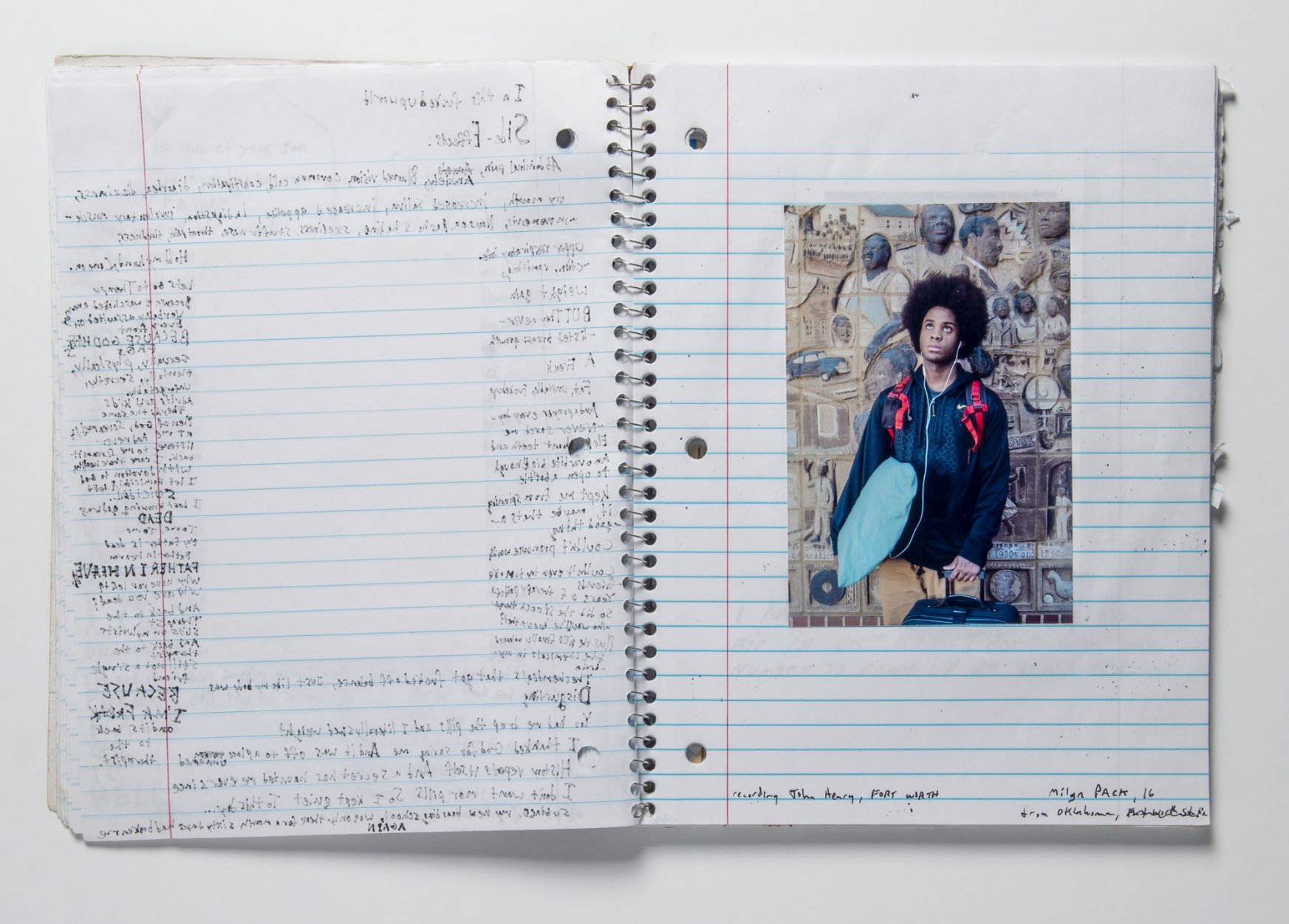

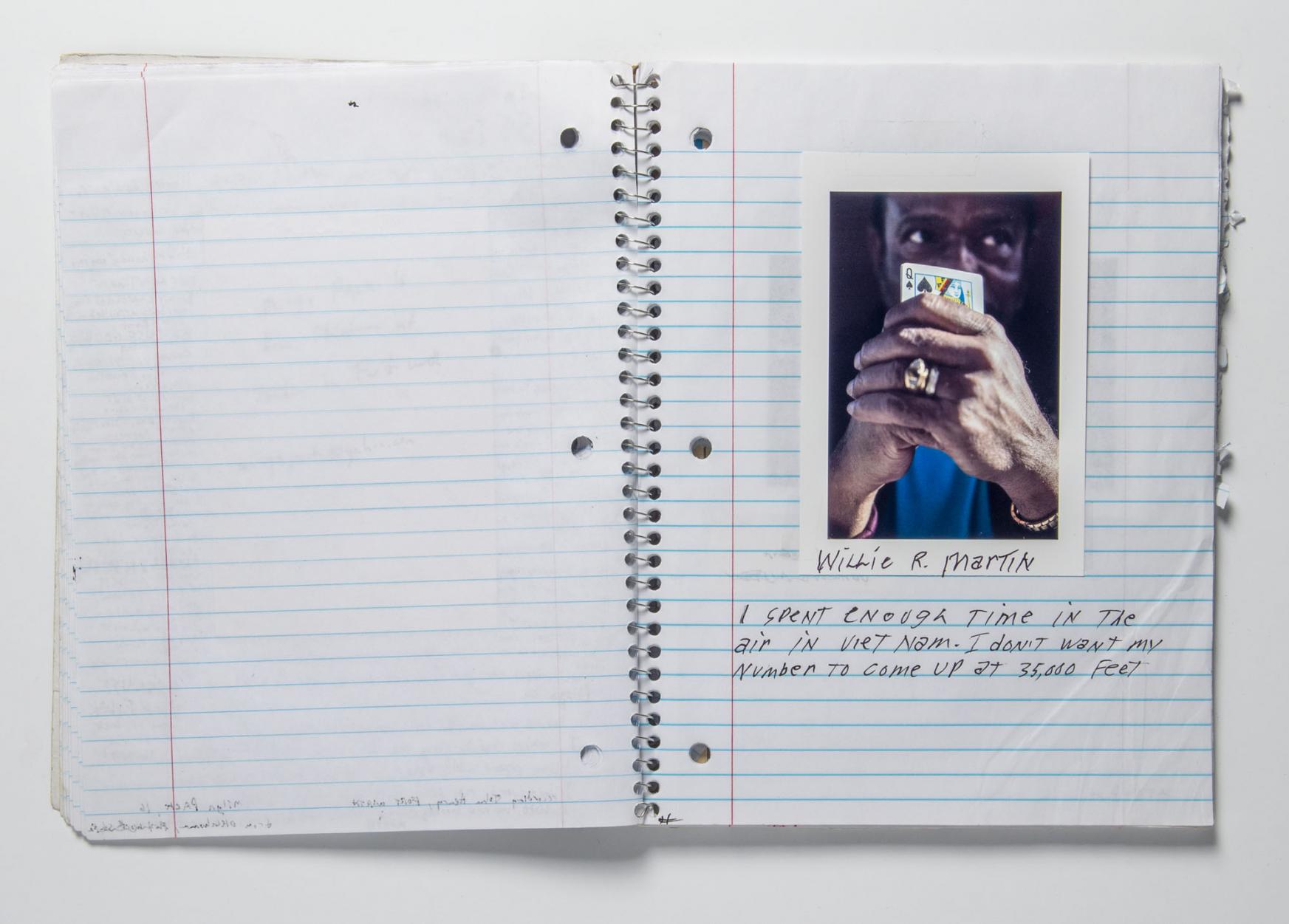

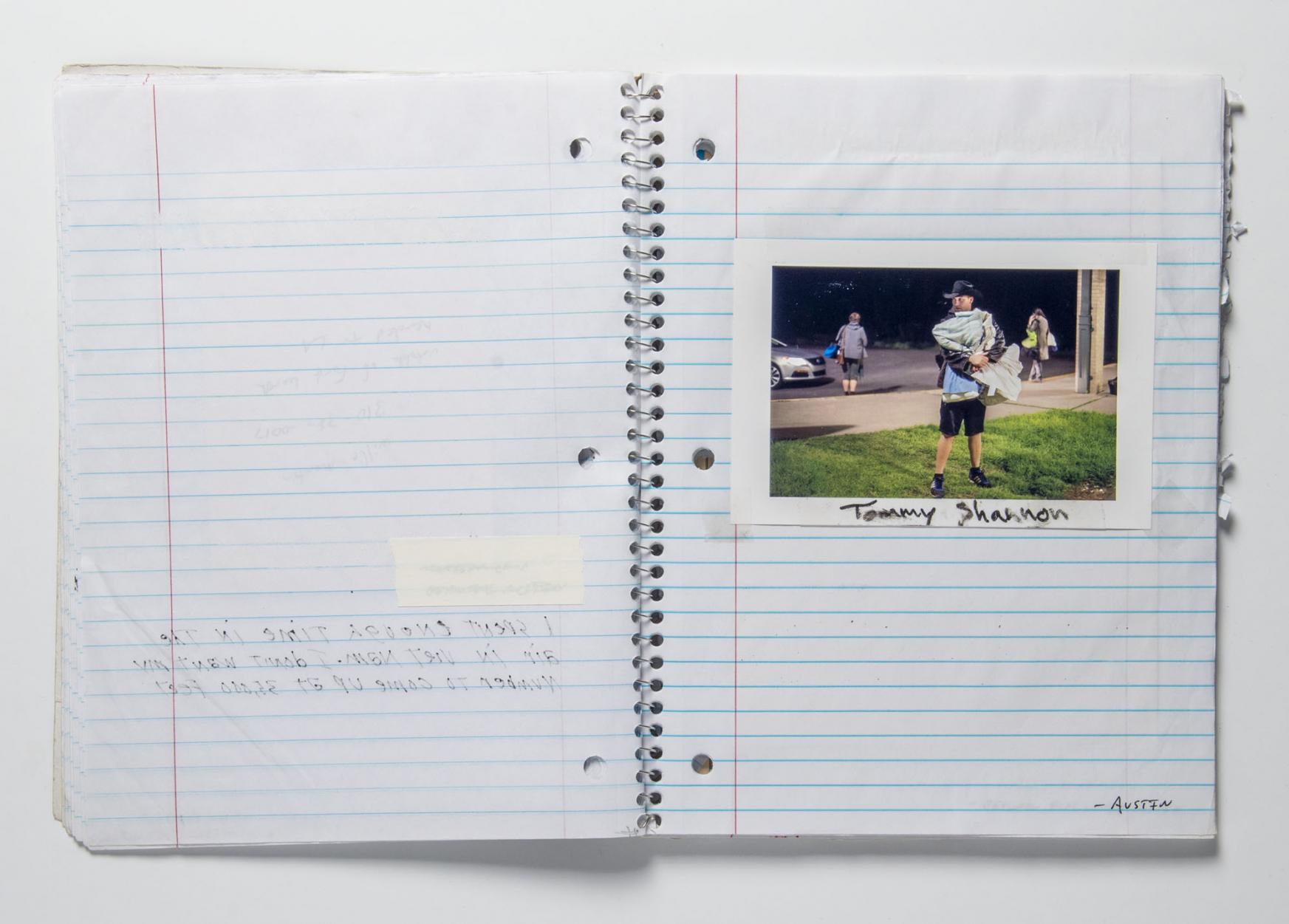

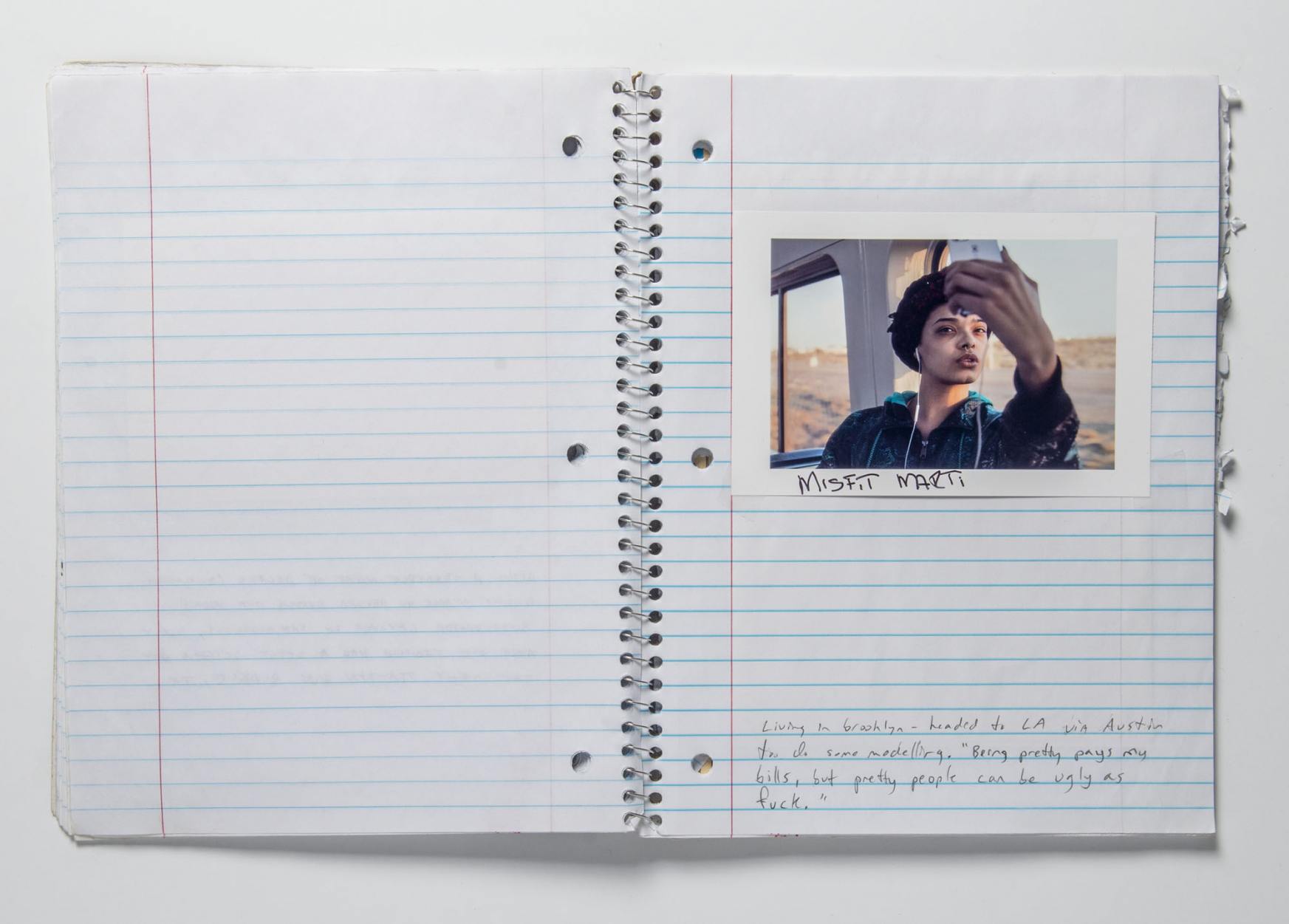

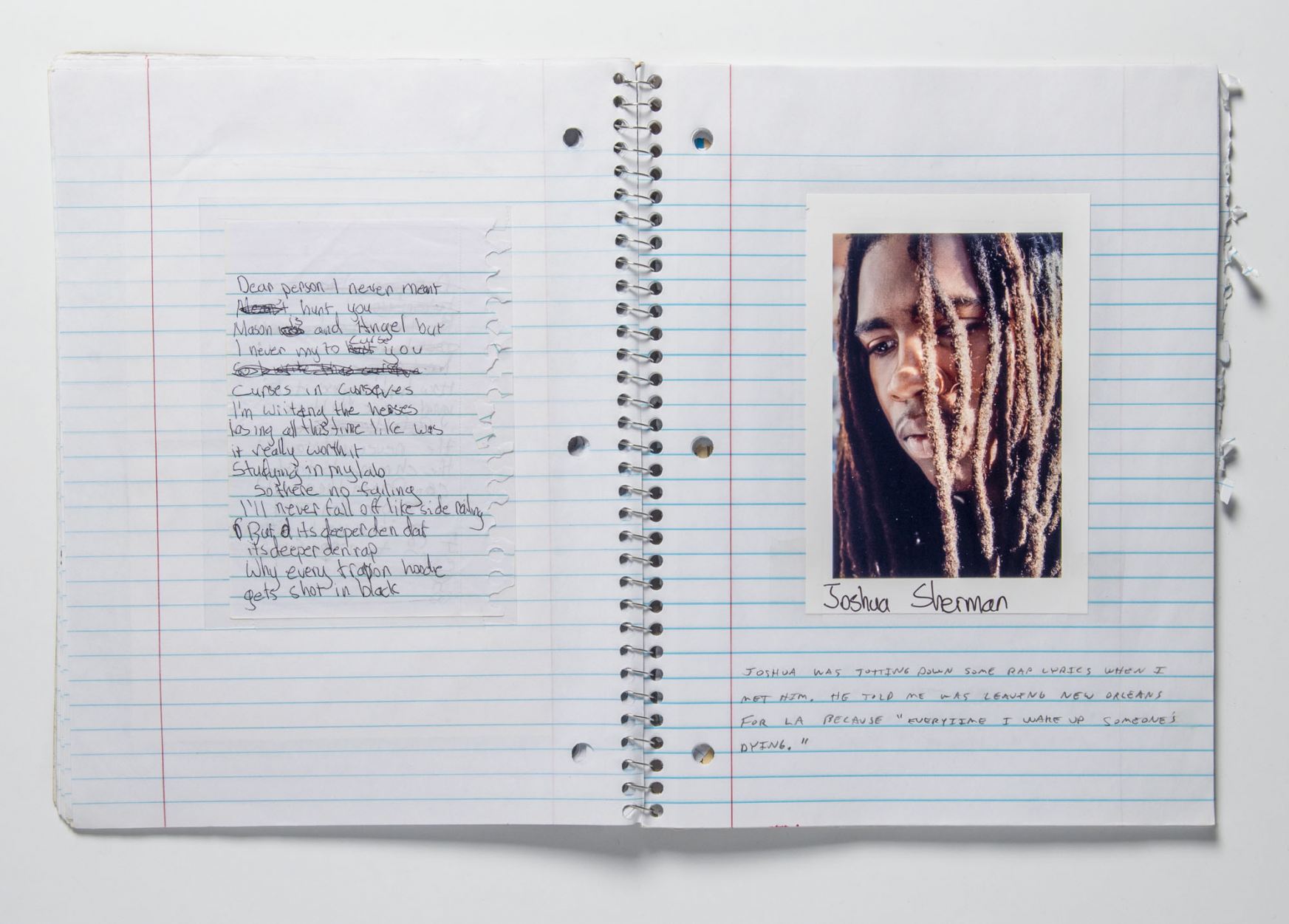

If you’ve ever traveled by Amtrak you know that (a) you have a lot of time on your hands (b) you meet a lot of characters. So along with documenting Billy for his album, I brought a portable printer and had my subjects write captions to their pictures in the style of photographers like Jim Goldberg and Wendy Ewald.

None of this work ever saw the light of day. The New York Times turned it down. Billy and Joe Purdy had a falling out and Billy rerecorded the project with Joe Henry a year later. I also became aware that my friend McNair Evans was working extensively on an Amtrak project. His work is a thousand times more realized than my short trip and I didn’t want to step on his toes. So the notebook went onto the shelf with dozens of other half-baked projects. It’s just as well. Along with being derivative of other photographers, it’s missing Billy’s voice. But looking at this notebook now during quarantine, it makes me hungry to make a mixtape and hit the road.

The (virtual) Lunch Table

Ethan: 12-year-old me is very much into watching The Last Dance on ESPN. 10/10

Amy: I stumbled upon a song by James Blake called “I’ll Come Too,” it’s about following a loved one with a desire to travel. What really got me was the video clip, it’s from BBC Earth and portrays kind of an impossible love story between a penguin and a seagull… Well, long story short, I didn’t expect to relate to a penguin so much. 9/10

Molly: Caroline Polachek’s album Drawing the Target Around the Arrow (2017), created under the initials CEP, is a gloomy invitation into a world she creates using synthesizers. It is uncertain at points, and incredibly calming at others. 7/10.

Alec: The song & video “Summer All Over” by Blake Mills slays me. 9/10