In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter

- Ex-Libris: Achter Glas by Joan van der Keuken

- Recently Received: The White Sky by Mimi Plumb

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Refresh the Map

- The Lunch Table

Picture and Poem

During a recent Zoom conversation with my collaborator C. Fausto Cabrera, he described the poet Jim Moore as “one of the founding poets that shaped my voice.”

Jim Moore got wind of this exchange (here), and passed along to me the nine-year-old blog post that Fausto referenced in our conversation:

People sometimes ask, especially parents of aspiring writers, “What does it take to become a poet?” From my own experience I would say four things matter most:

1) A broken heart.

2) A sudden dislocation which results in you living in a new place, not really knowing why you are there.

3) A welcoming bookstore floor.

4) The luck of stumbling across a poet whose work seems written as if just for you; whose poems feel as if they are saving your life, stanza by blessed stanza.

Everything else takes care of itself.

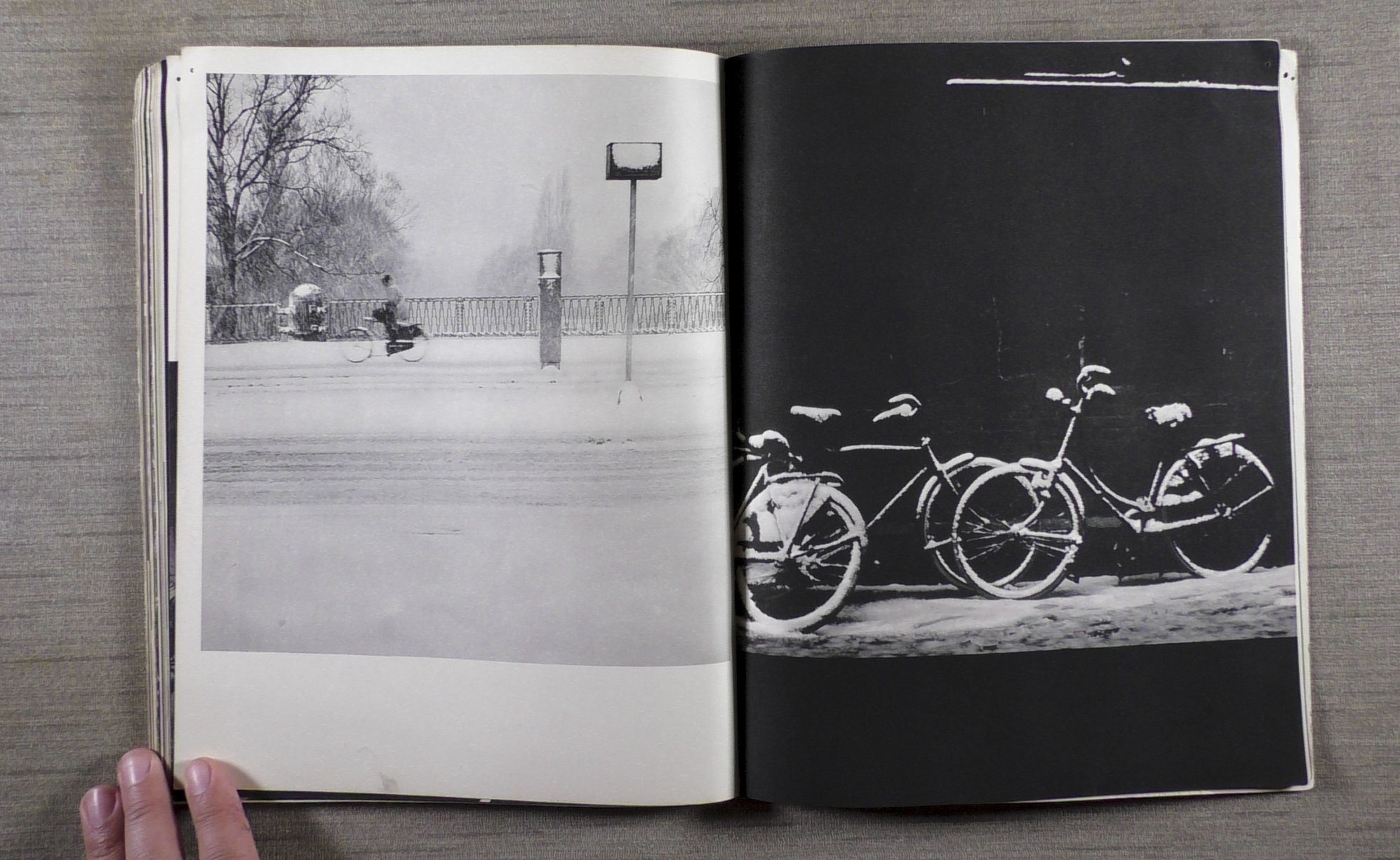

At nineteen I had all of the ingredients for Moore’s recipe. I was in college on the East Coast and utterly friendless. “A broken heart at nineteen is not hard to come by,” writes Moore. Instead of a bookstore floor I had the college library where I spent much of my time reading wintery literature that fed my homesickness for Minnesota. A favorite was Robert Bly’s first book, Silence in Snowy Fields, (1962), and this poem:

Driving to Town Late to Mail a Letter

It is a cold and snowy night. The main street is deserted.

The only things moving are swirls of snow.

As I lift the mailbox door, I feel its cold iron.

There is a privacy I love in this snowy night.

Driving around, I will waste more time.

When I discovered the photography section of the library and Summer Nights by Robert Adams on its shelves, my life was changed. With this book, I found the medium that suited my longing for moody wandering, albeit in the wrong season.

So when New York was hit with a heavy snowstorm, I took to the deserted streets of Bronxville.

The pictures I made that night are not remarkable. I was still using my dad’s Canon AE-1 and cropped the pictures square to make them look more pro. Nor is there anything conceptually compelling. But the feeling I had that night is still important to me now.

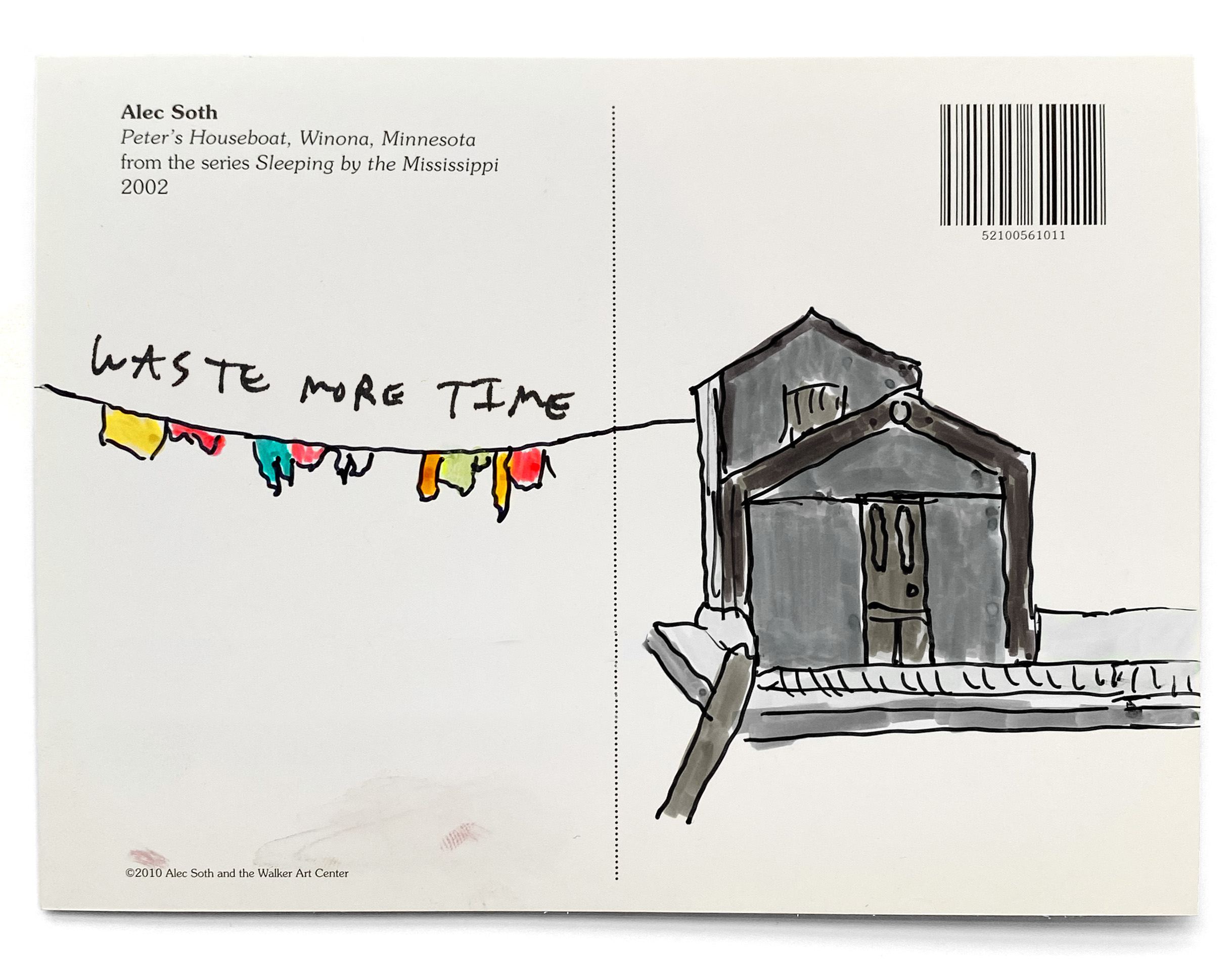

A few customers of our LBM postcard sale have asked me to jot down advice. “Try holding onto the feeling you had when you first fell in love with art,” I wrote to one. I made another card with Bly’s words which I’m keeping for myself: “Waste more time.”

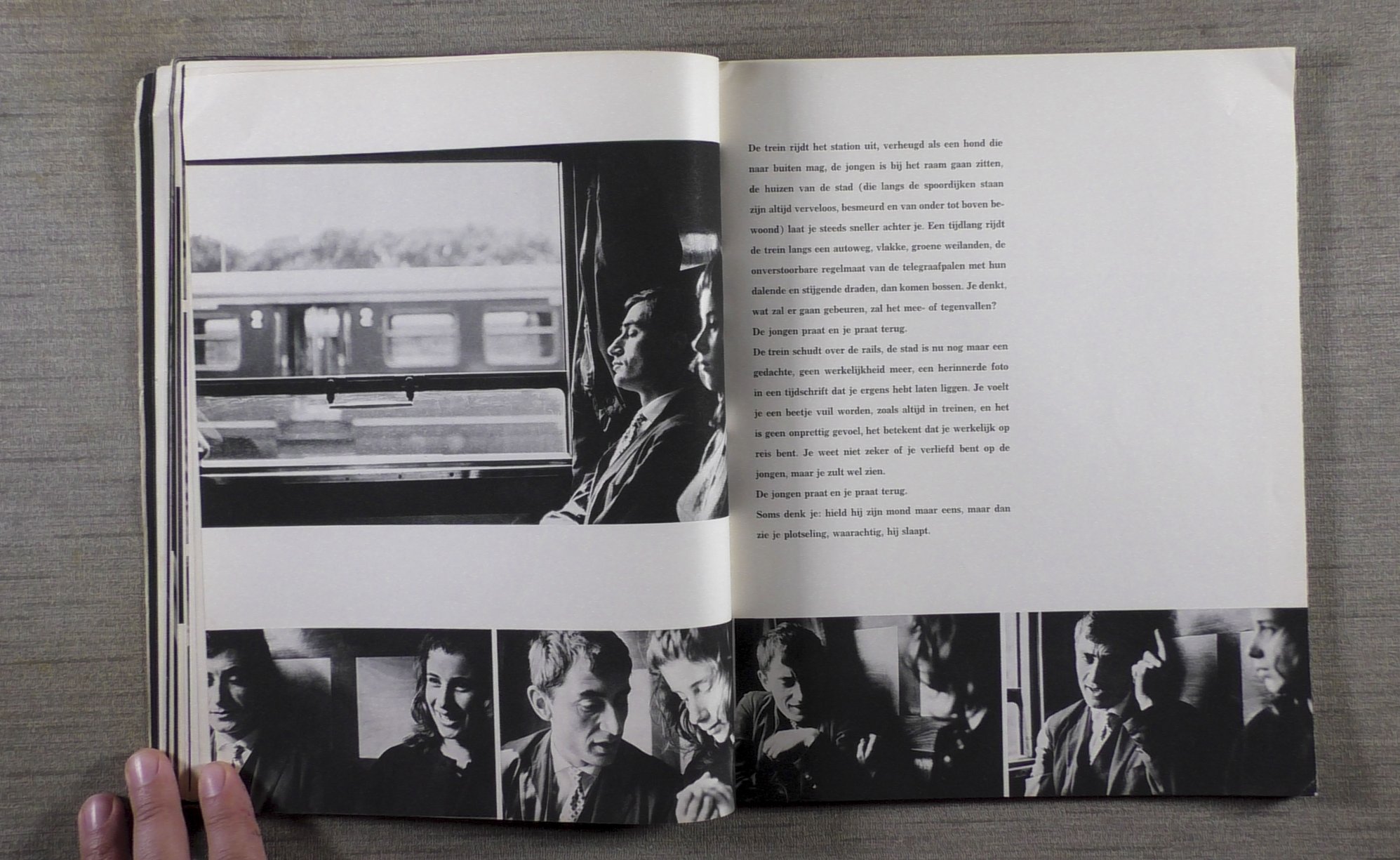

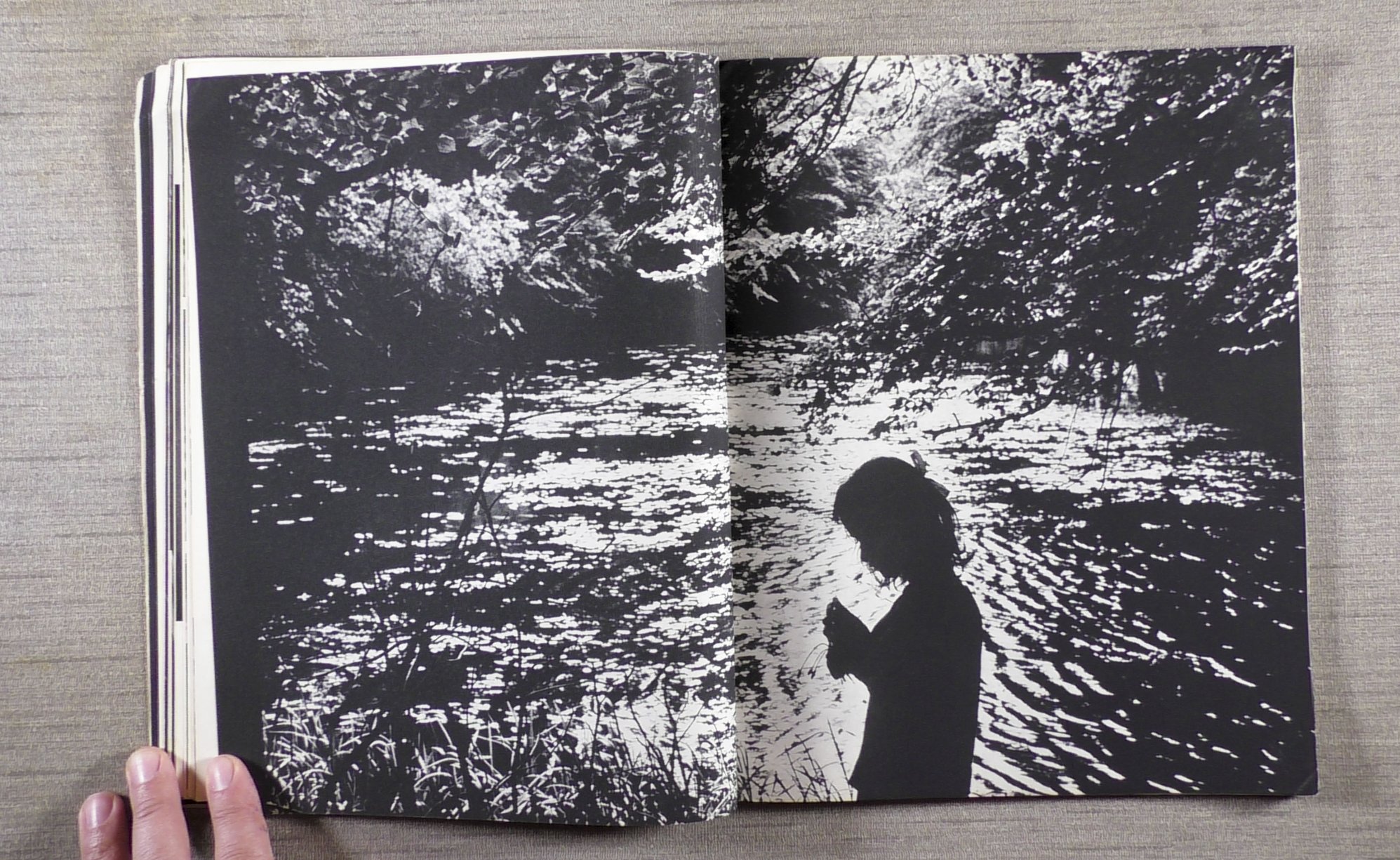

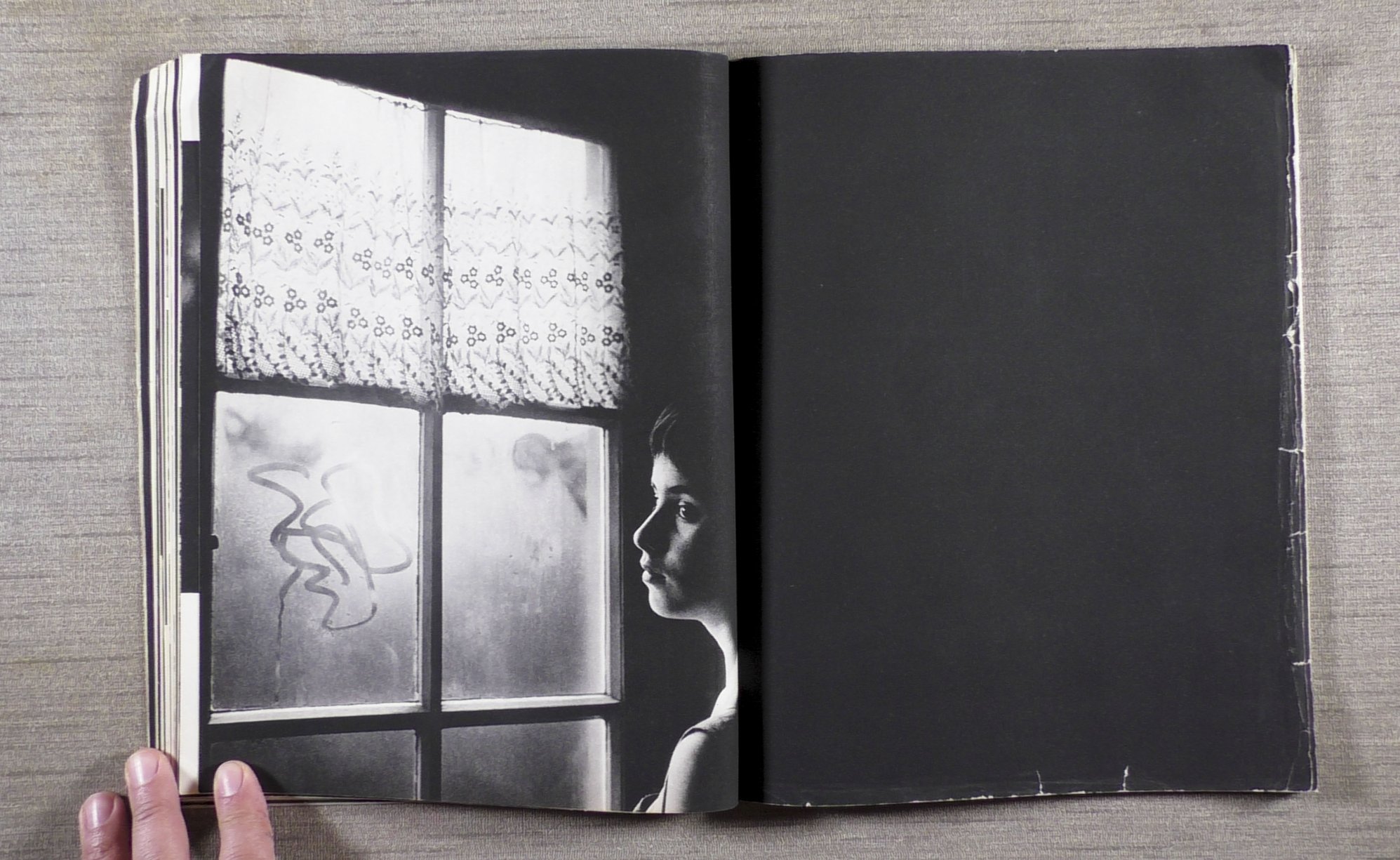

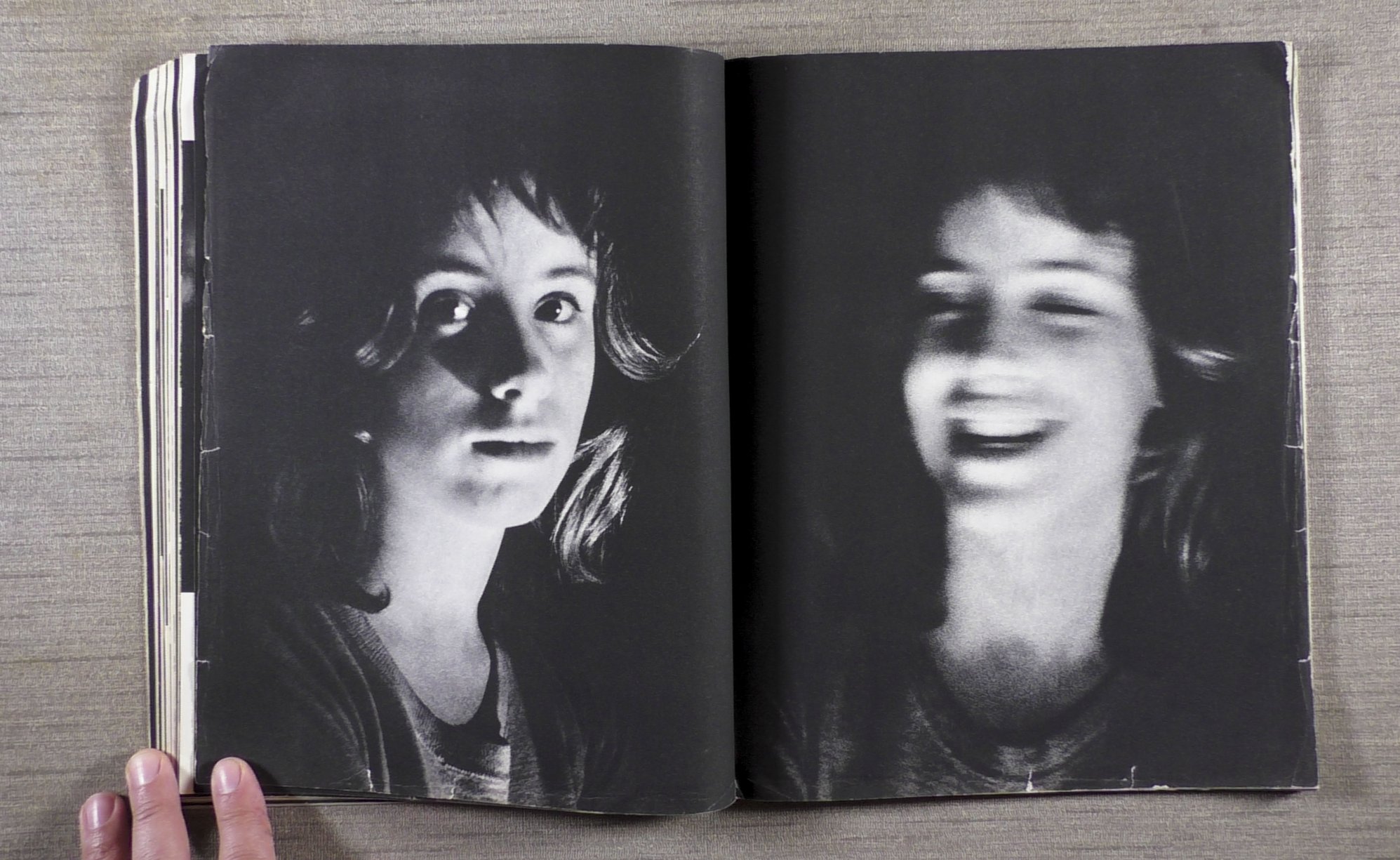

Ex-Libris: Achter Glas by Joan van der Keuken

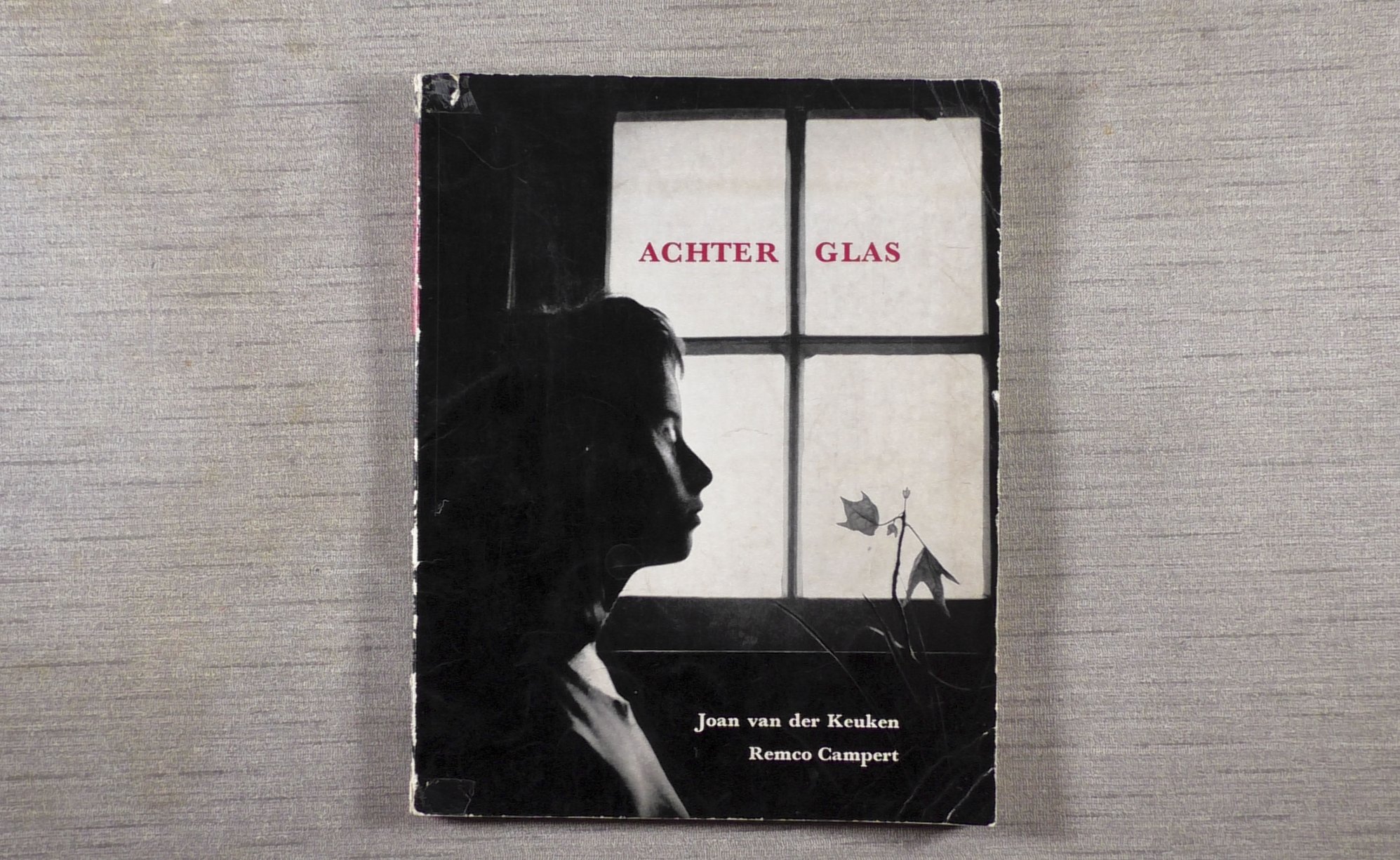

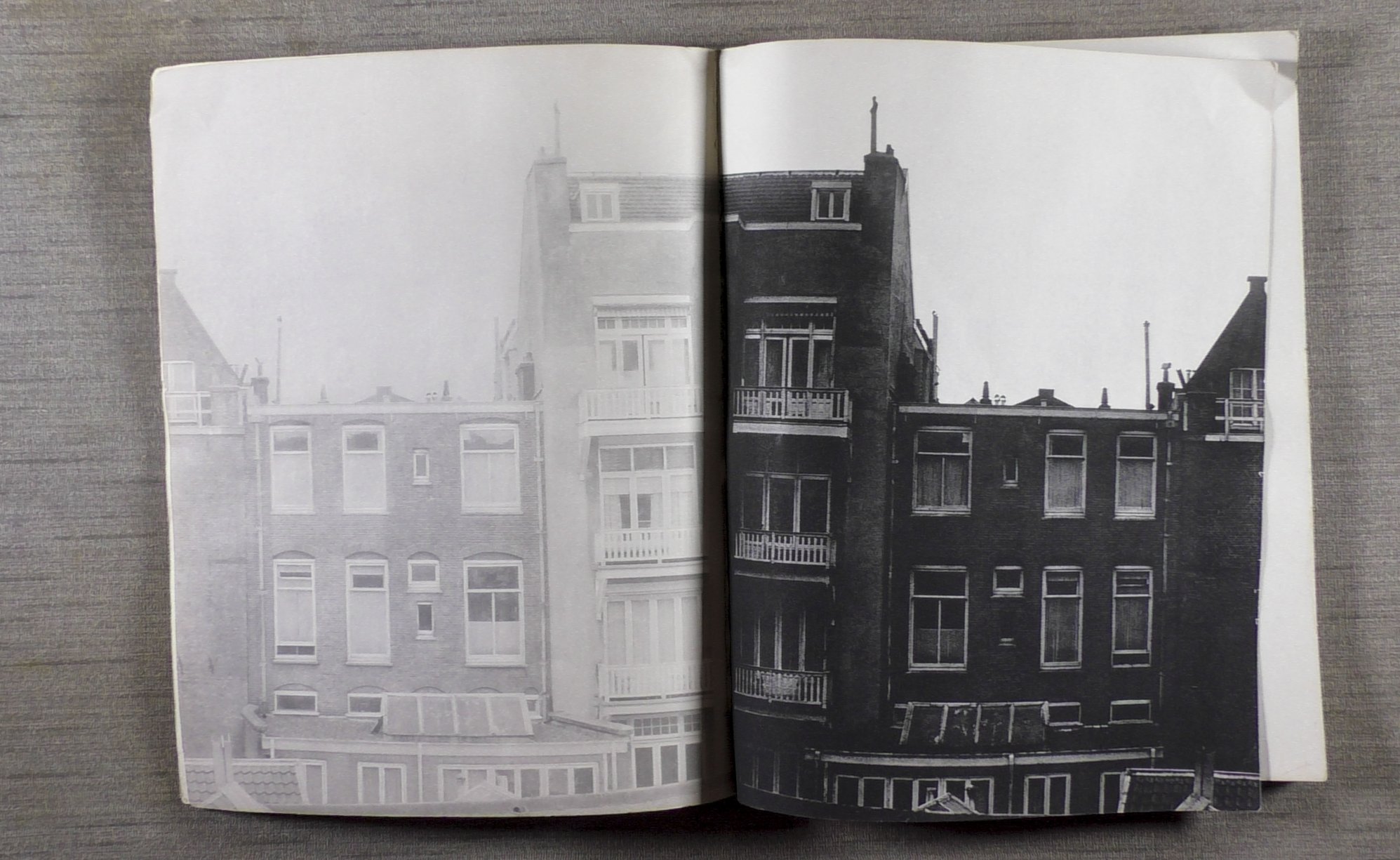

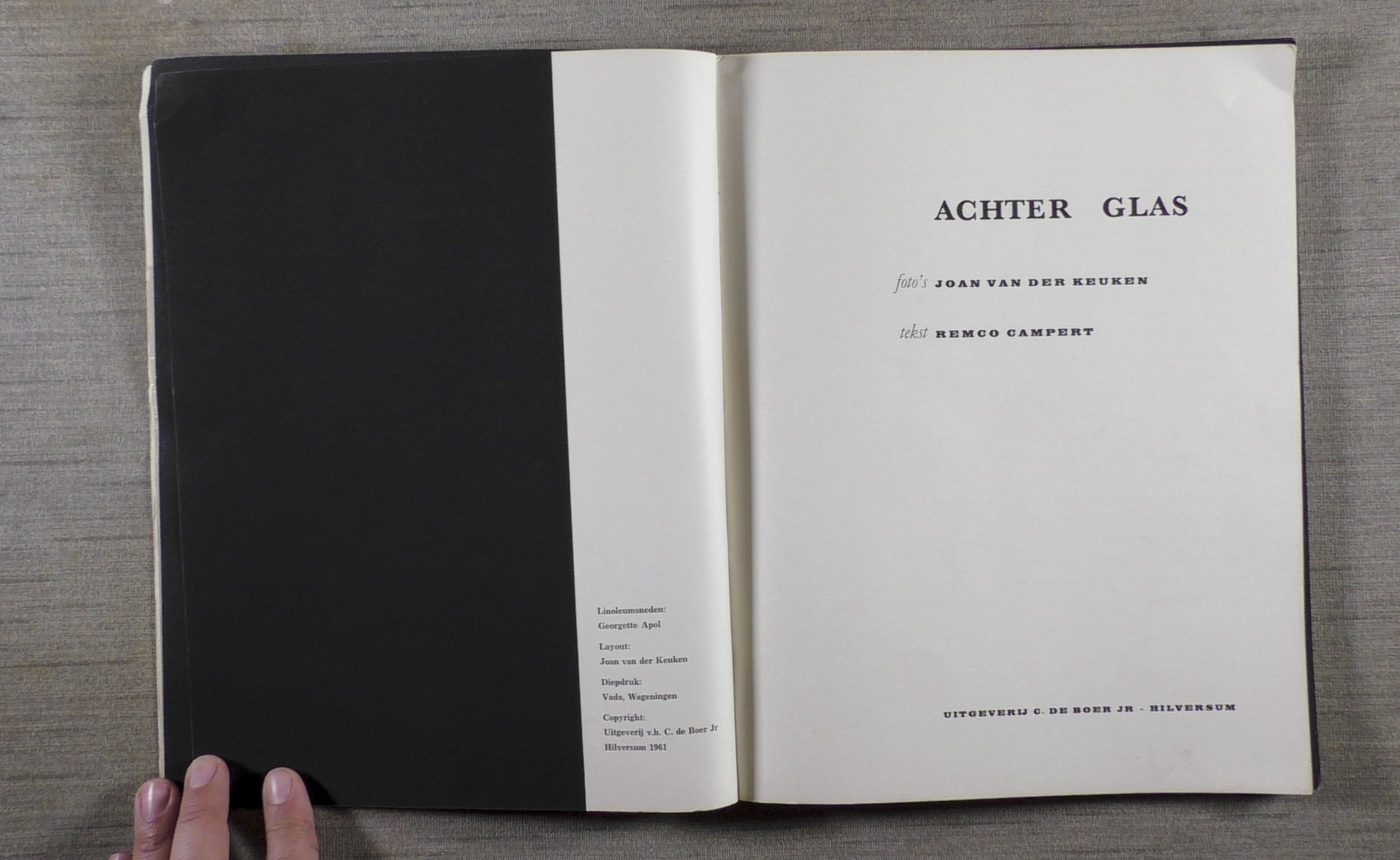

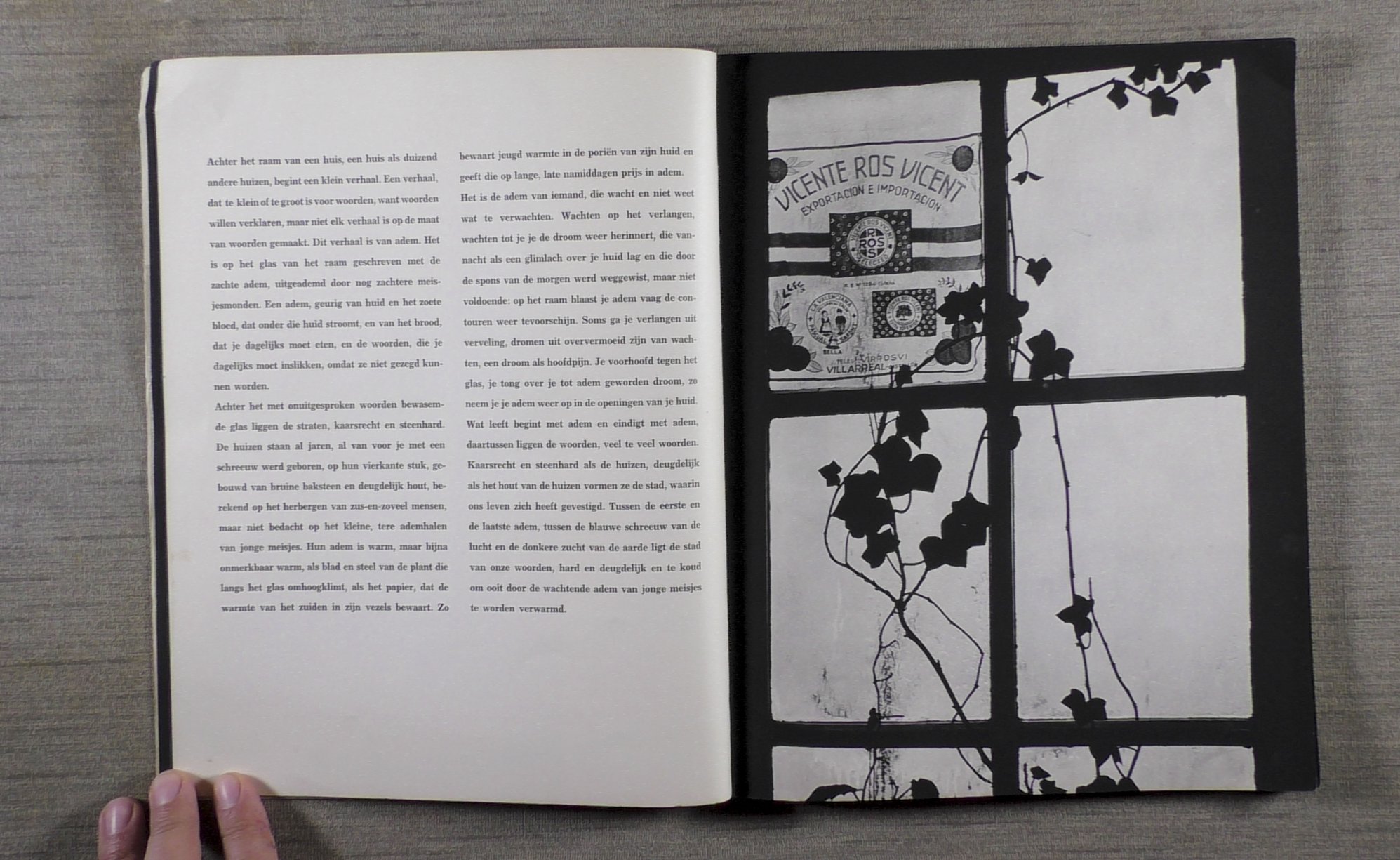

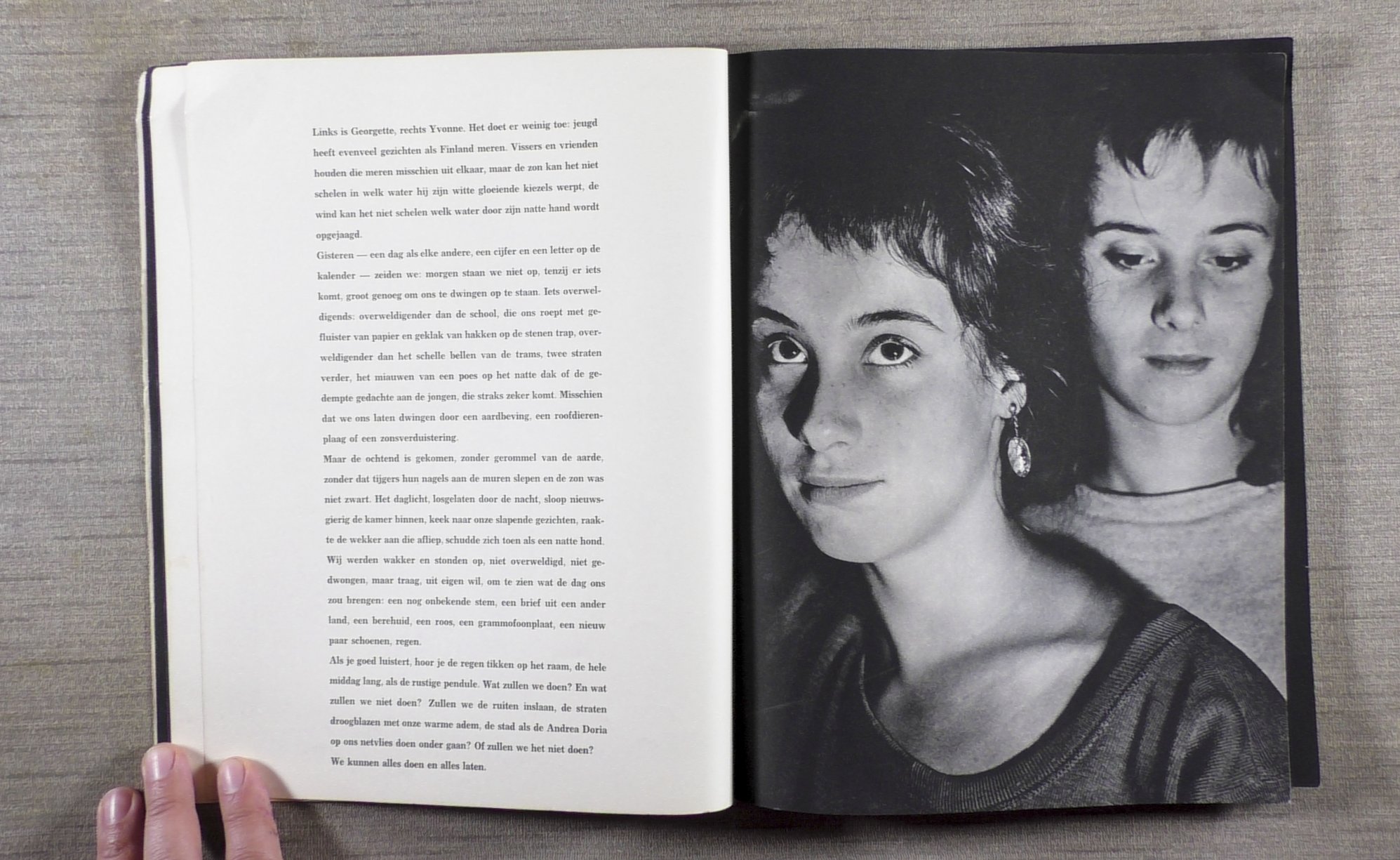

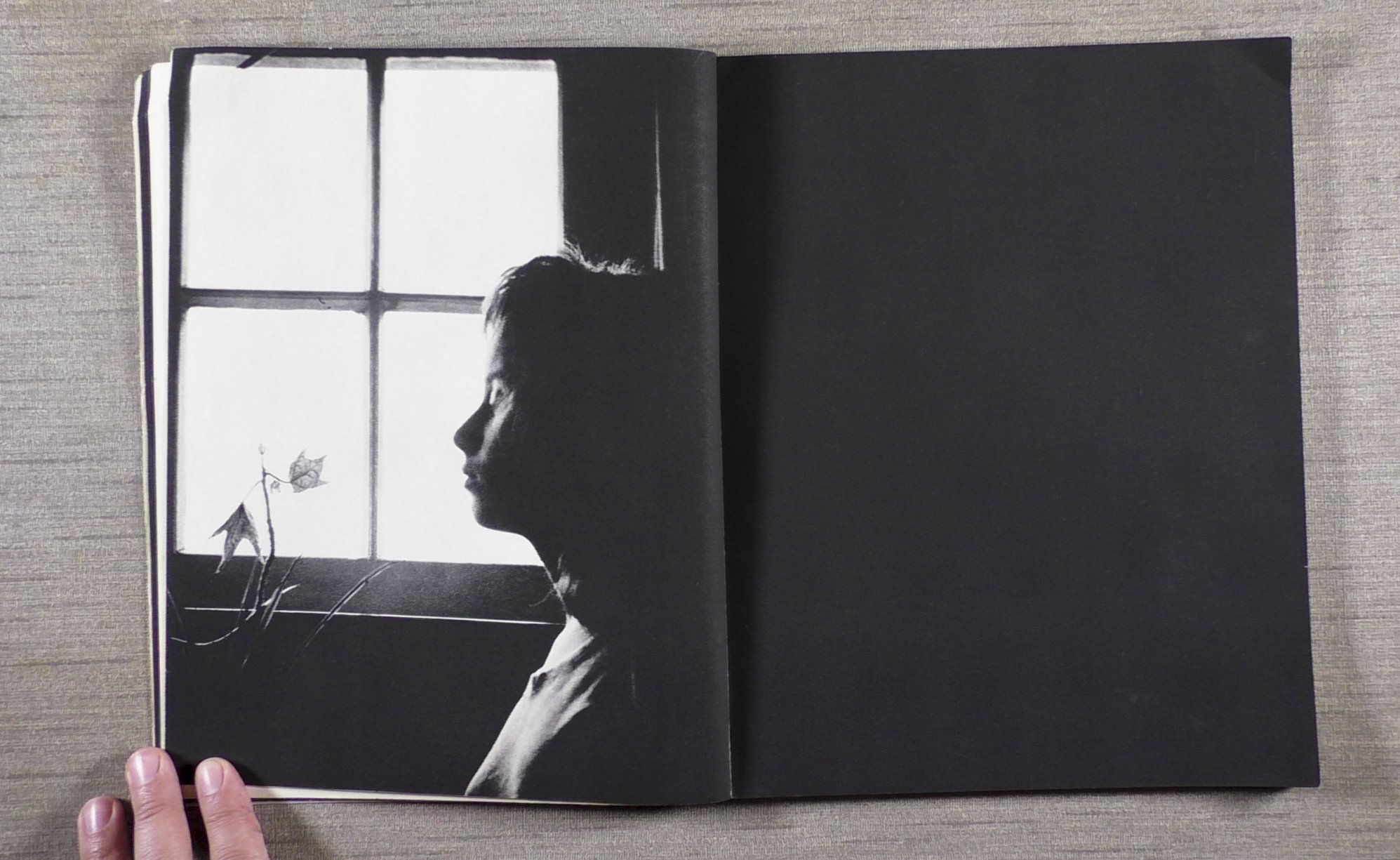

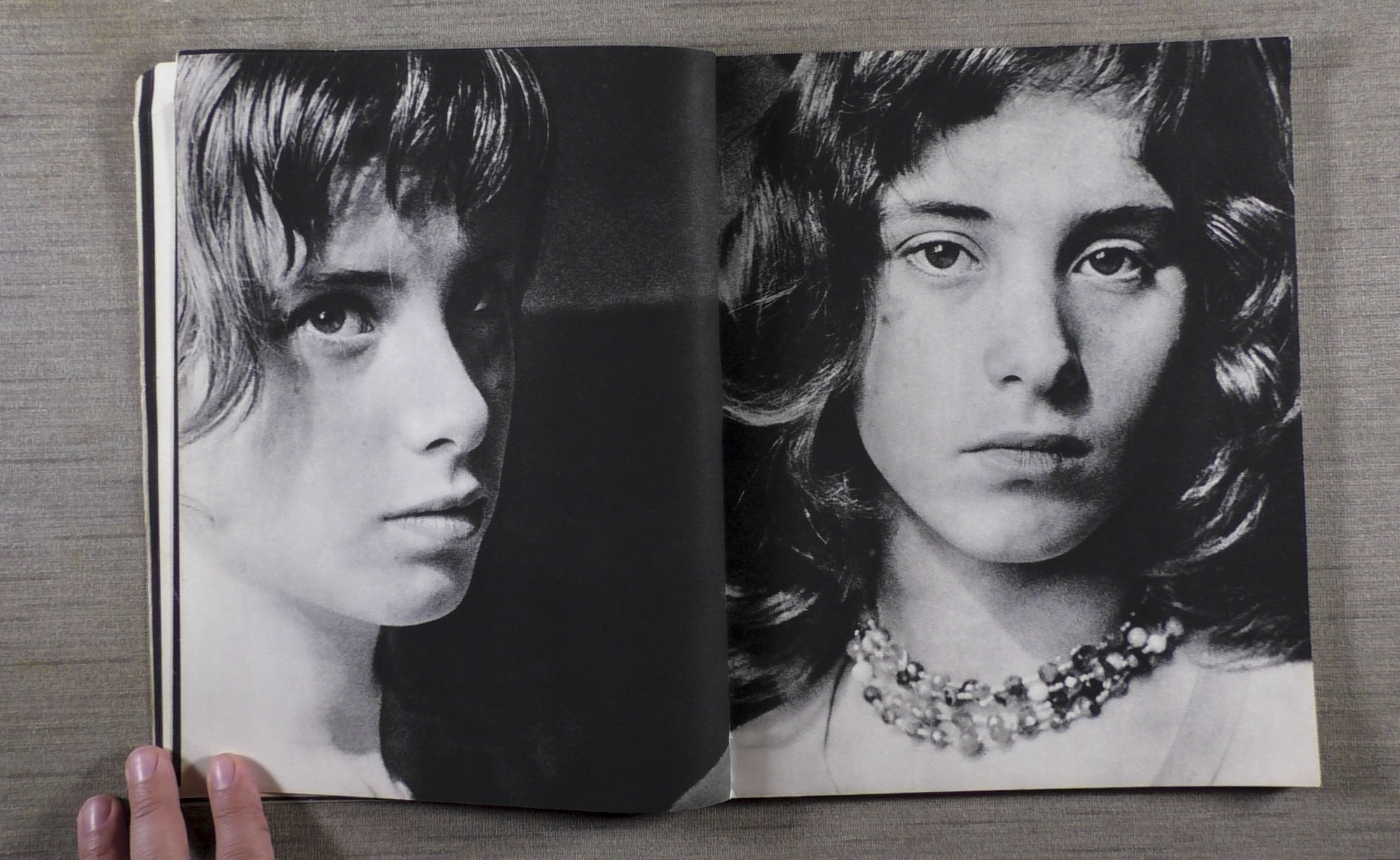

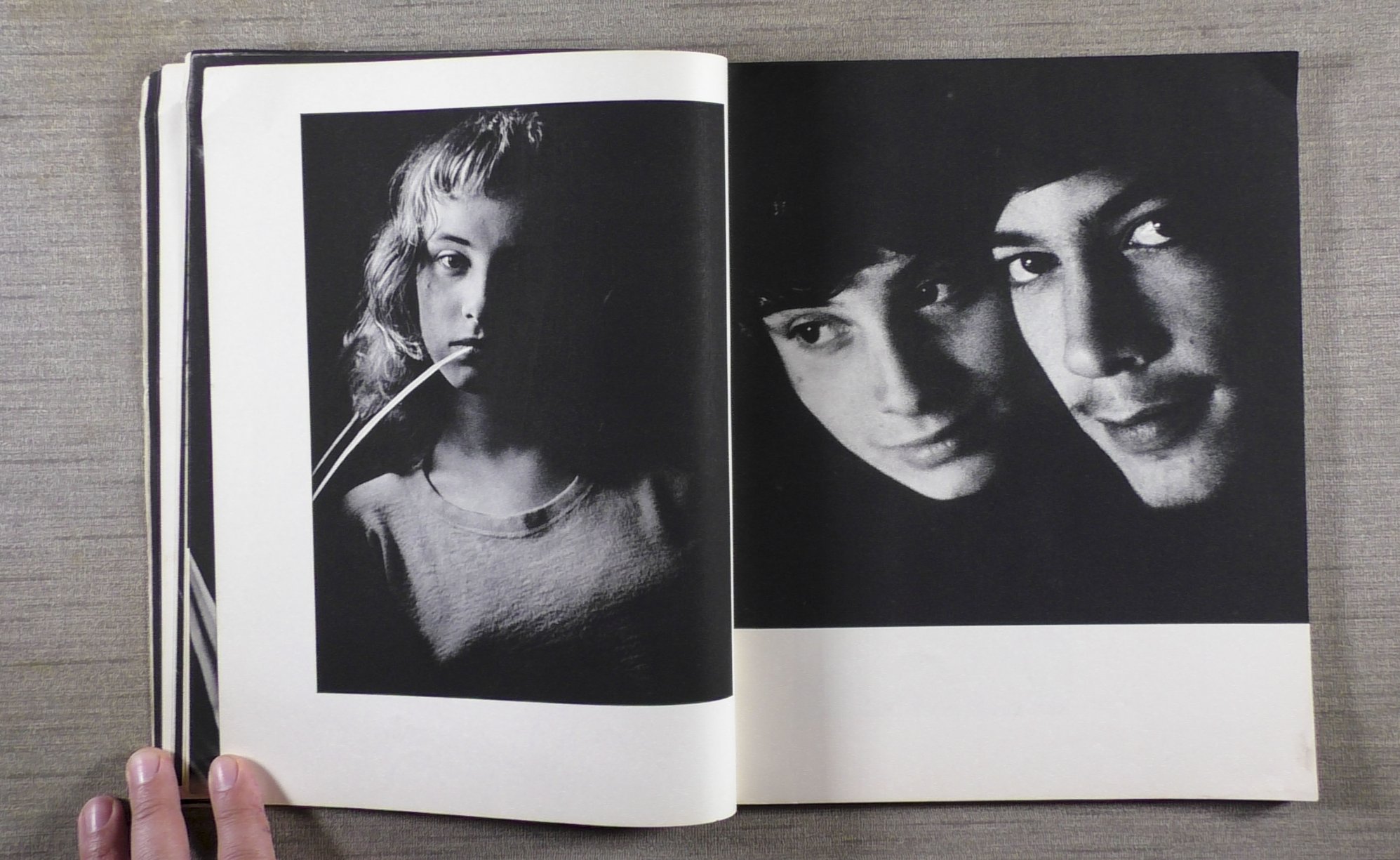

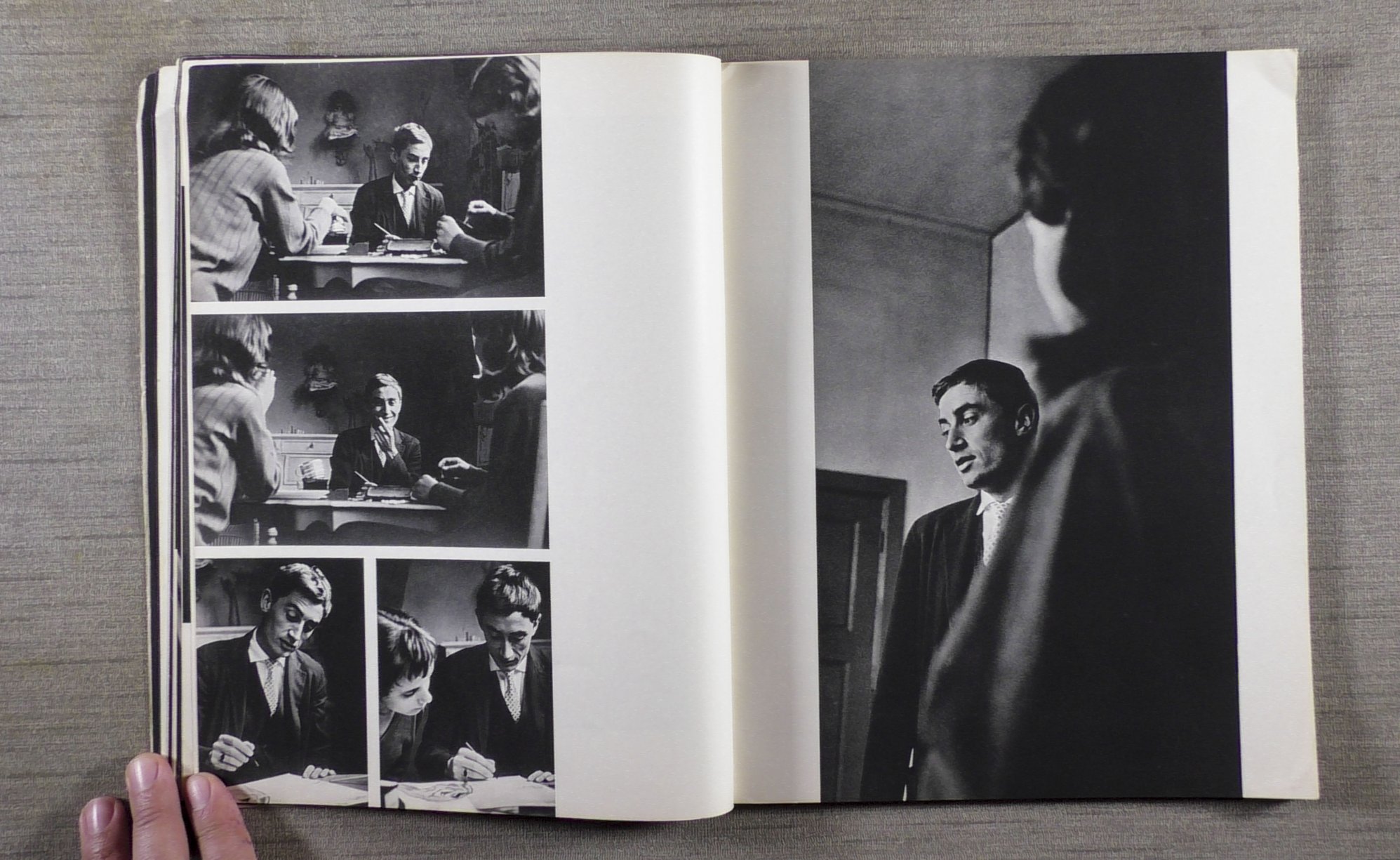

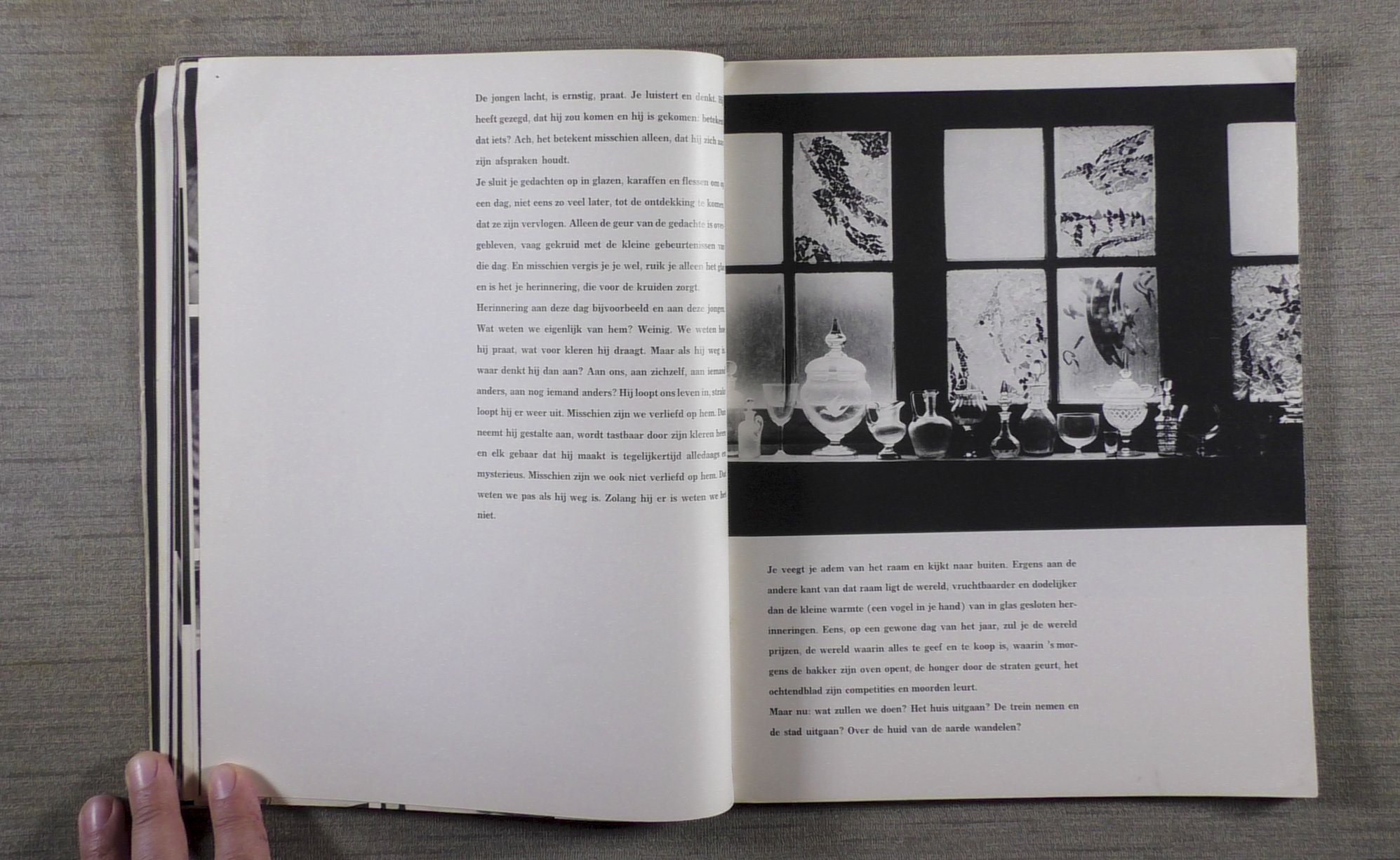

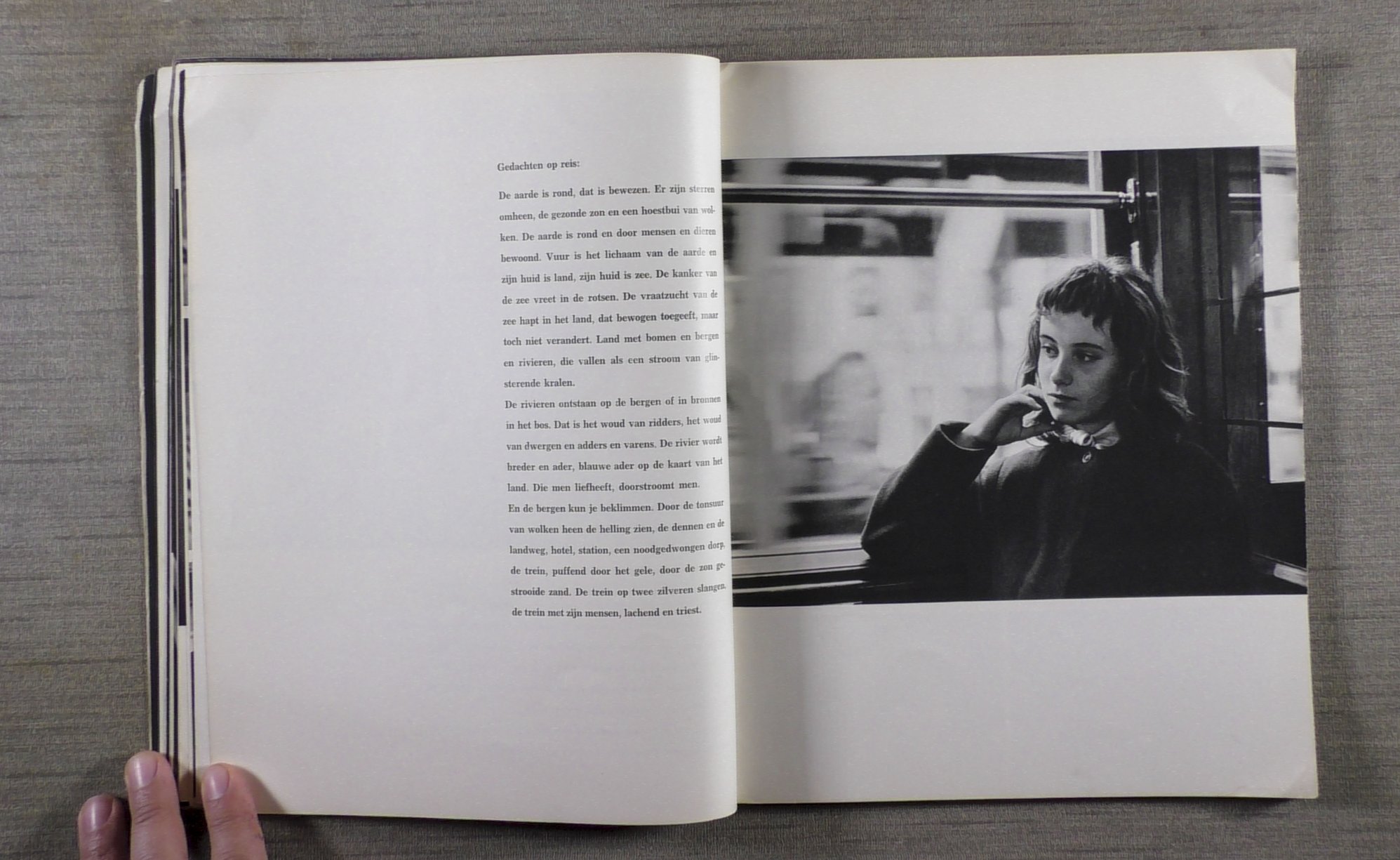

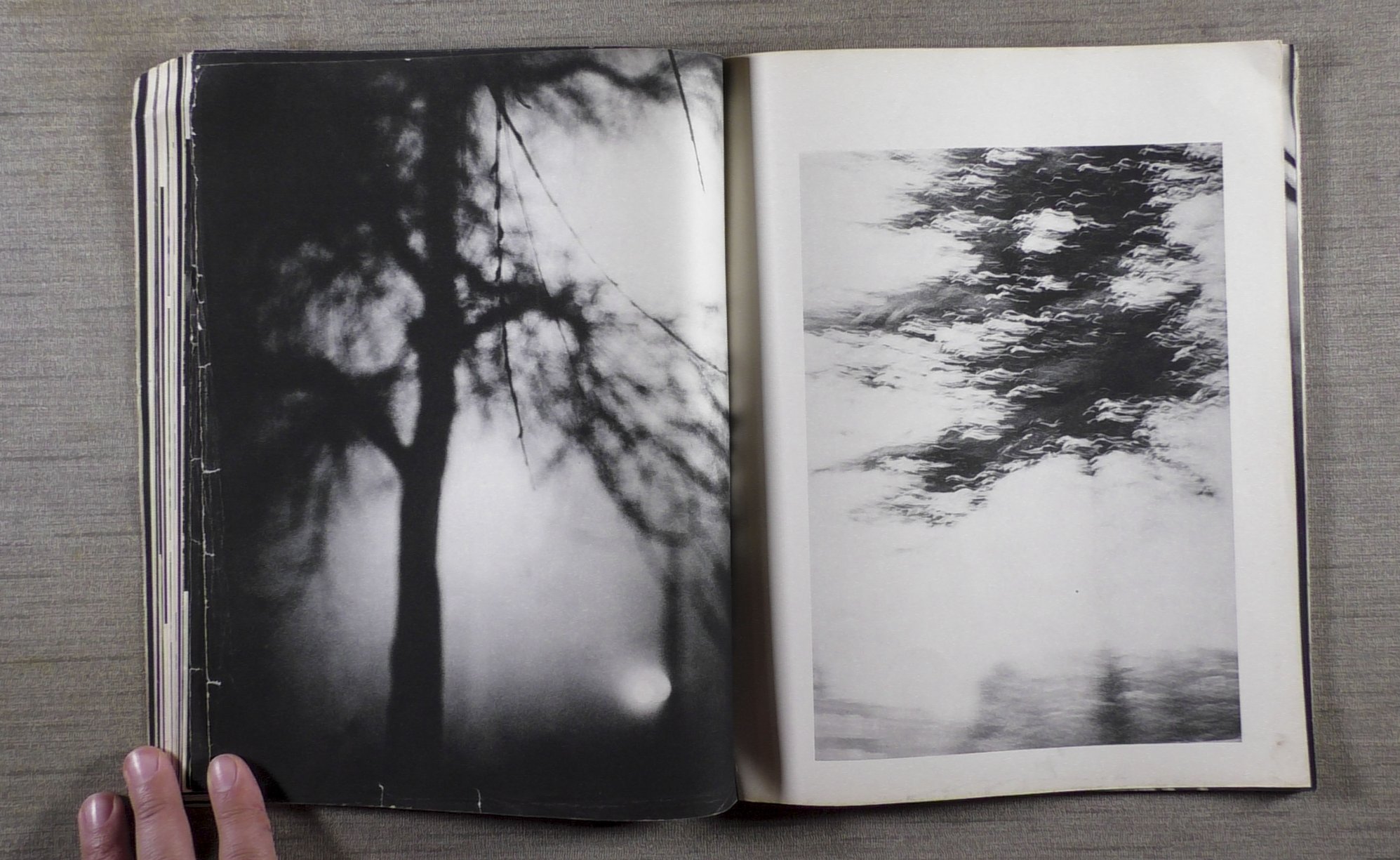

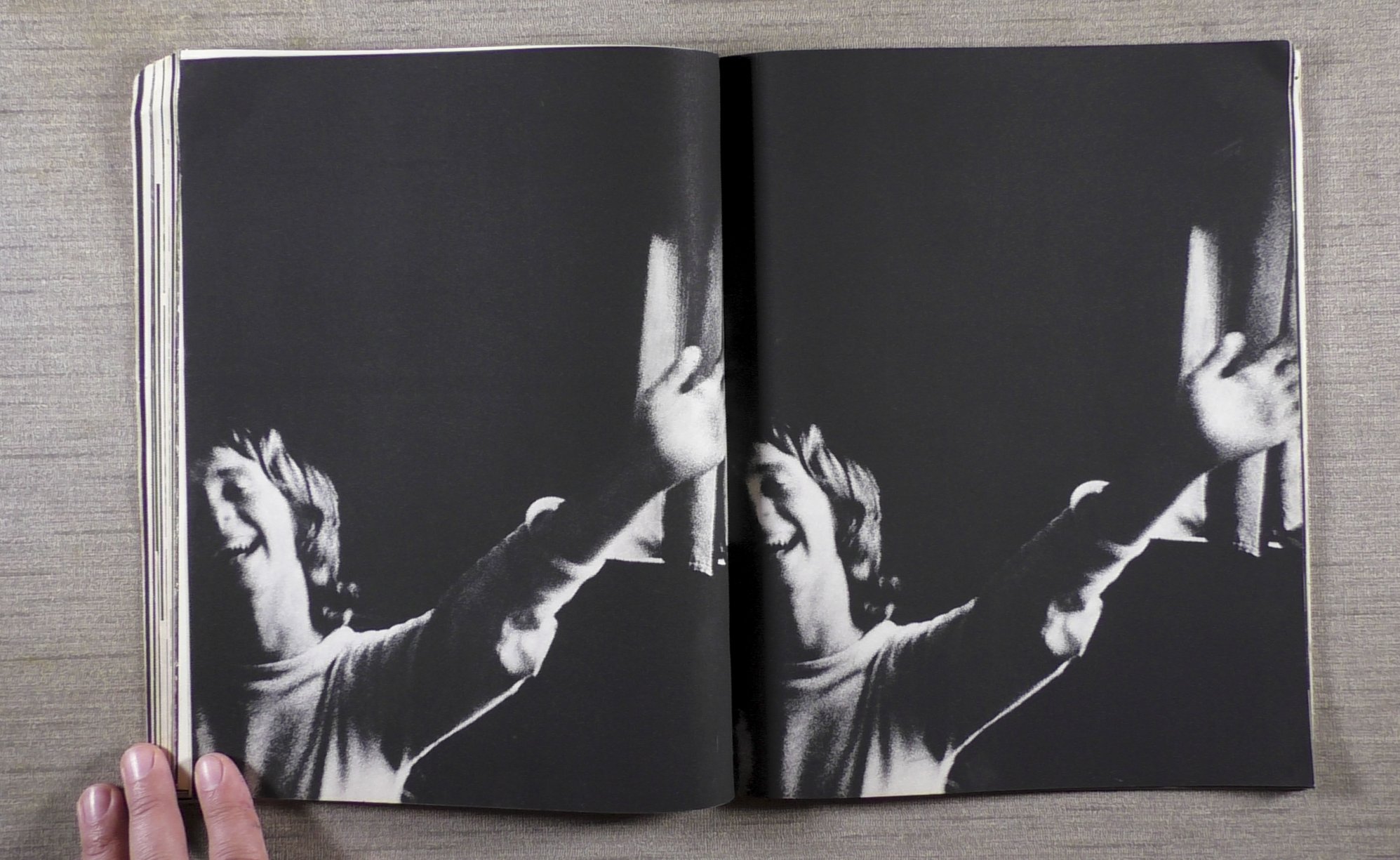

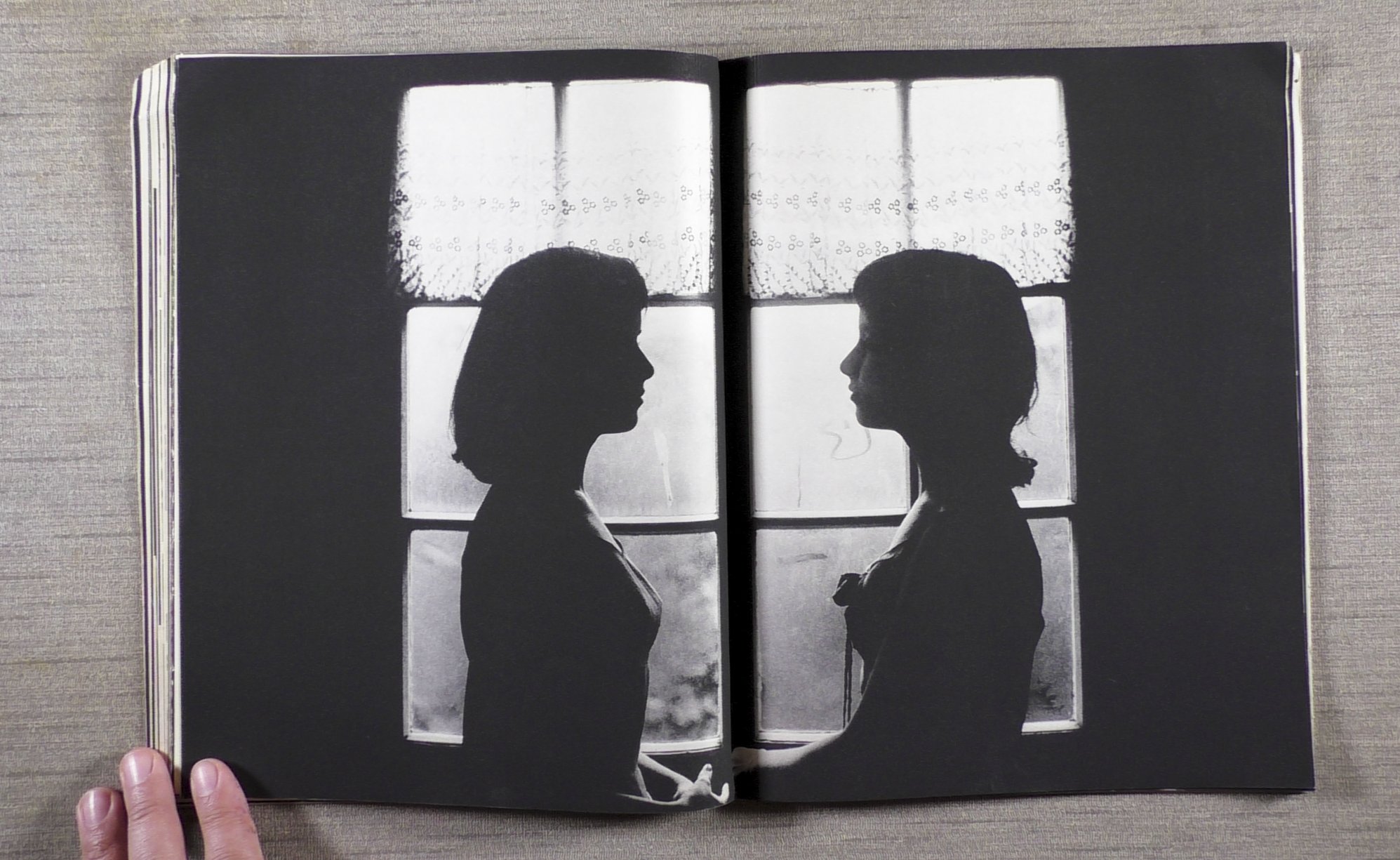

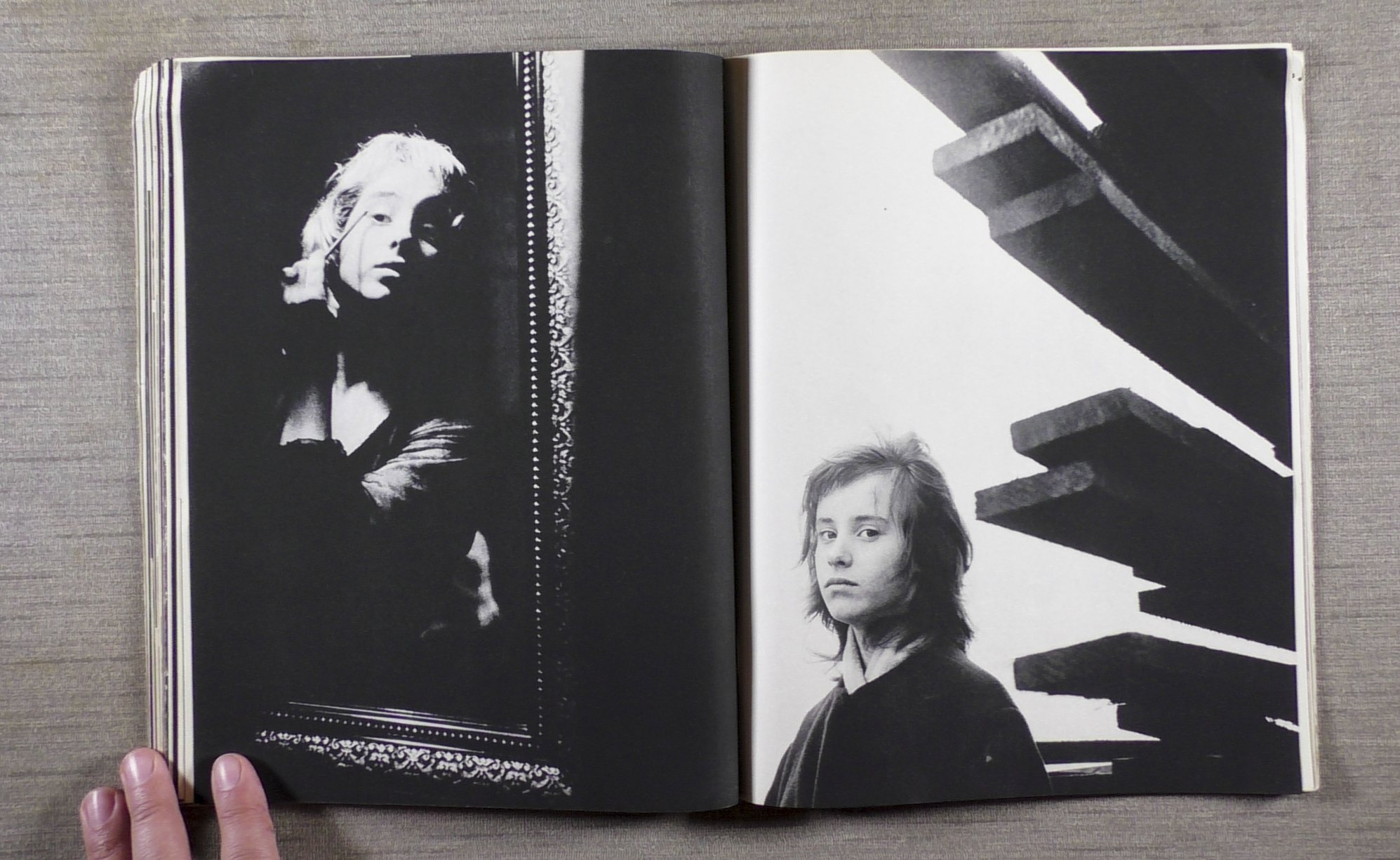

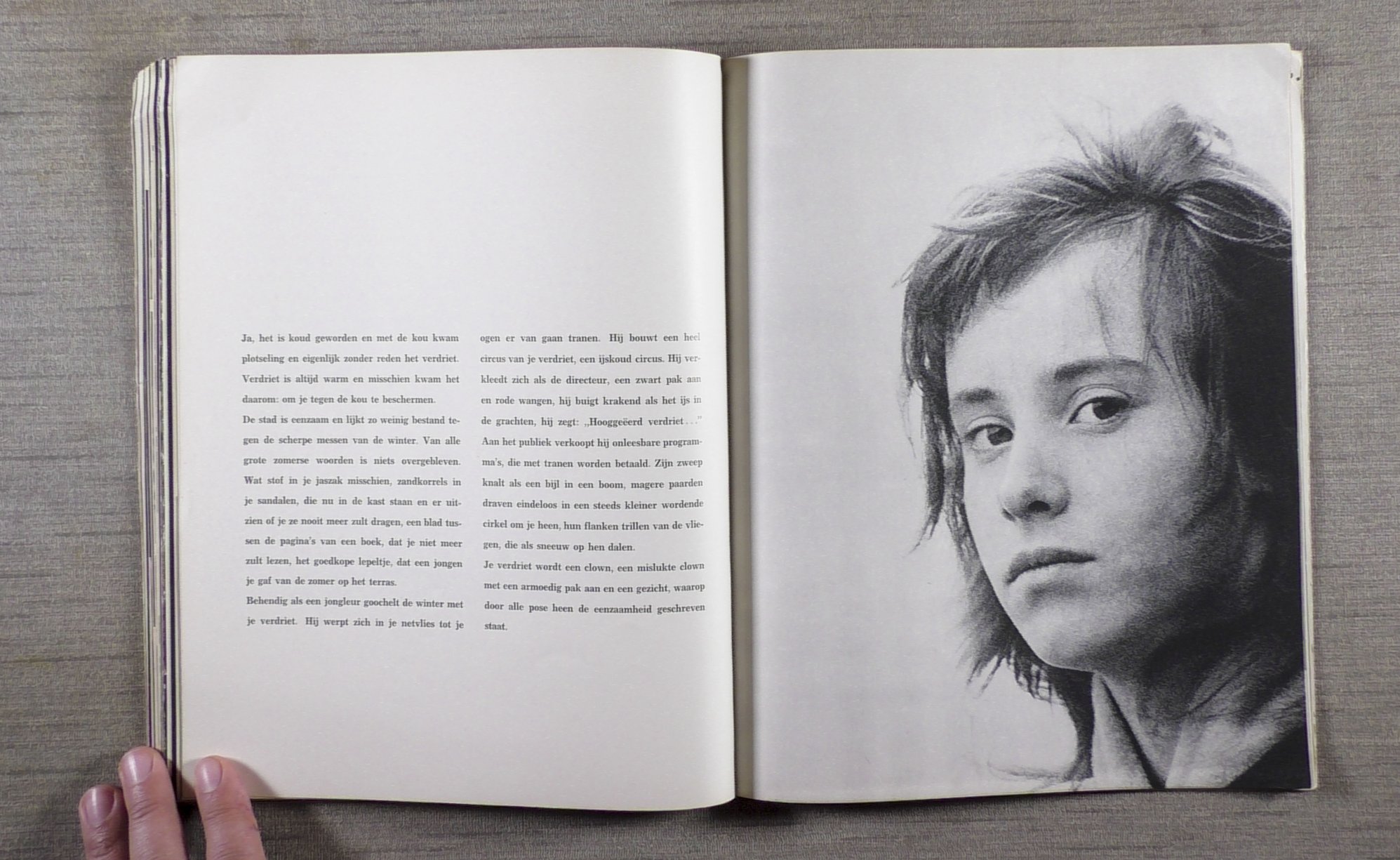

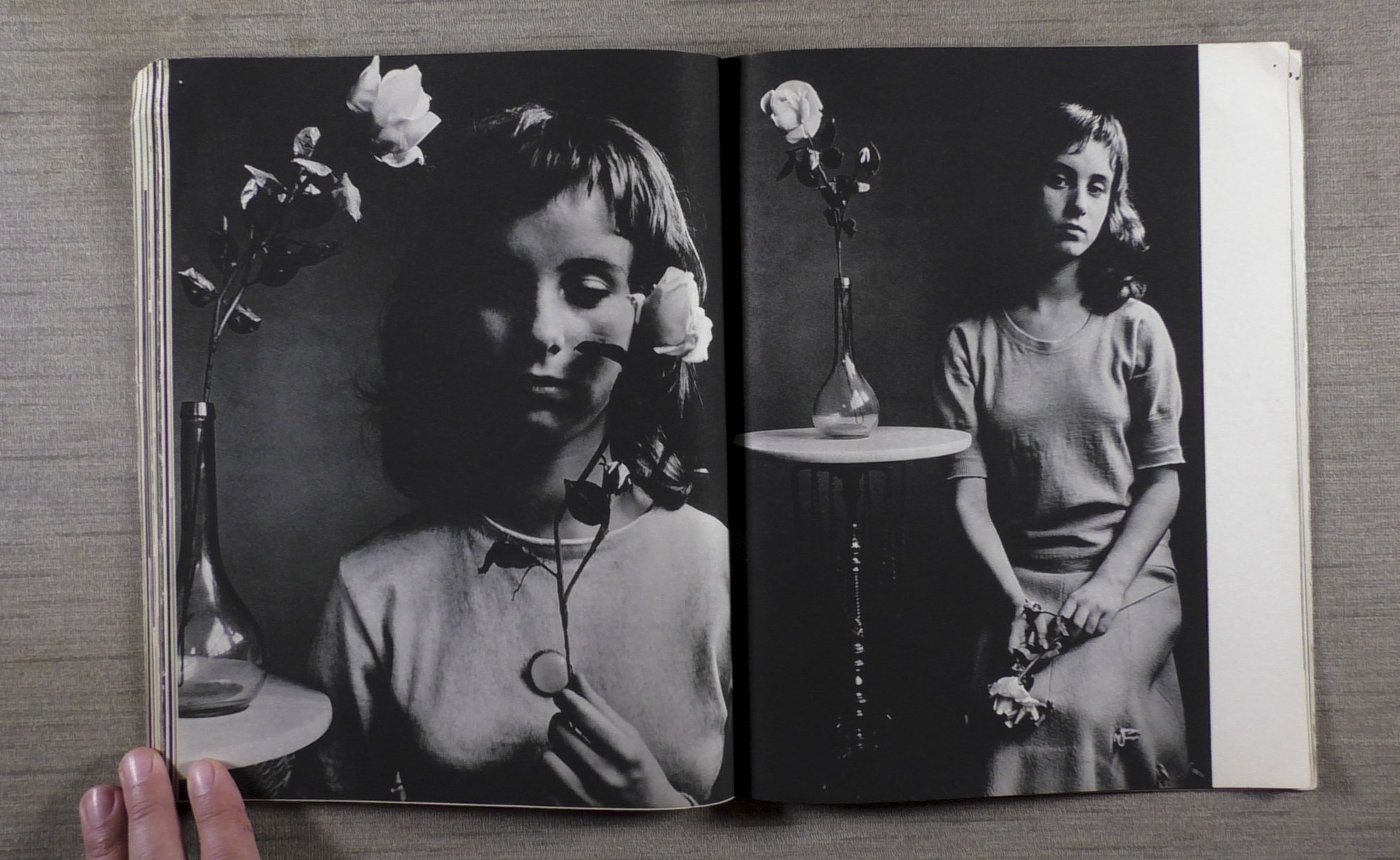

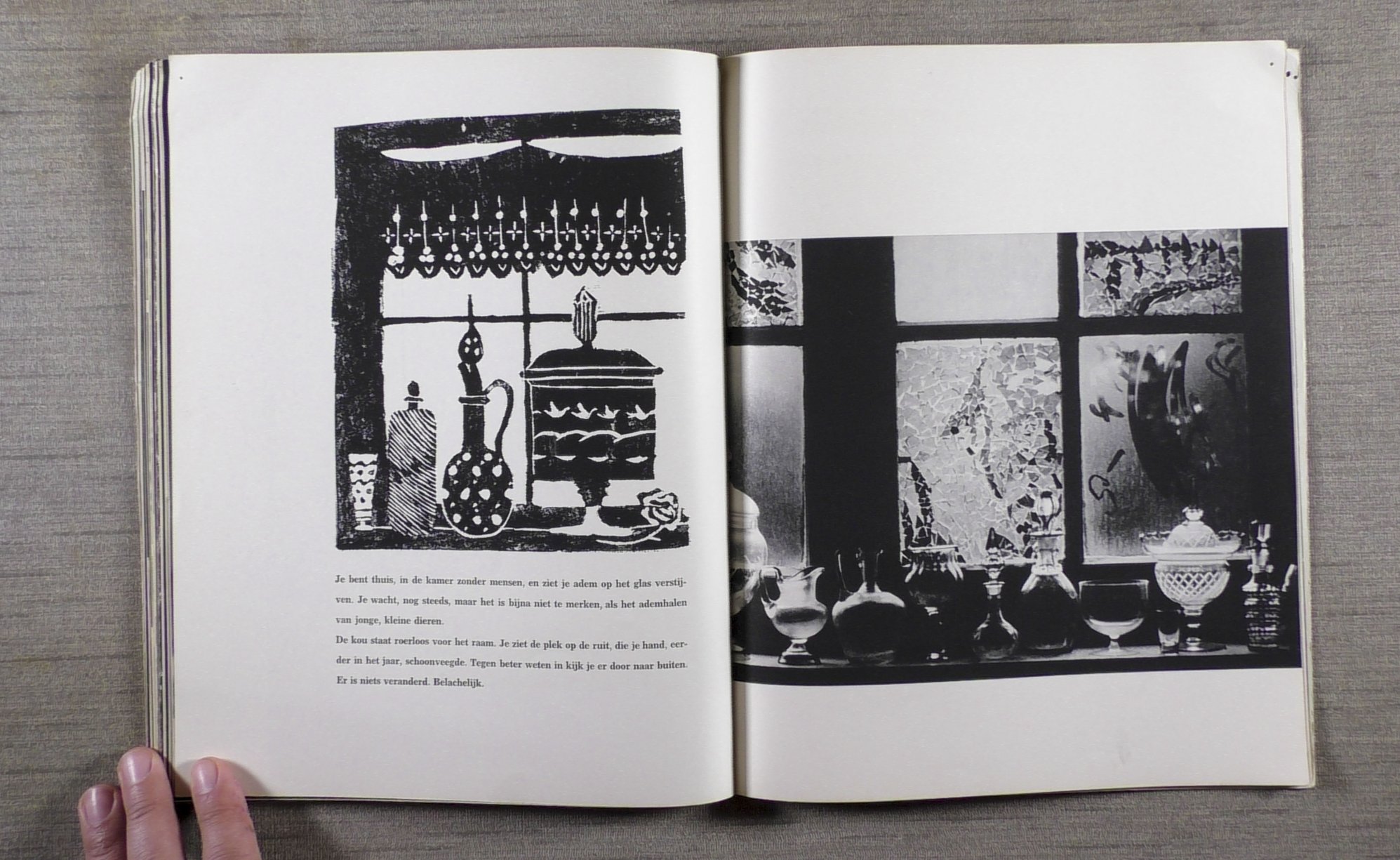

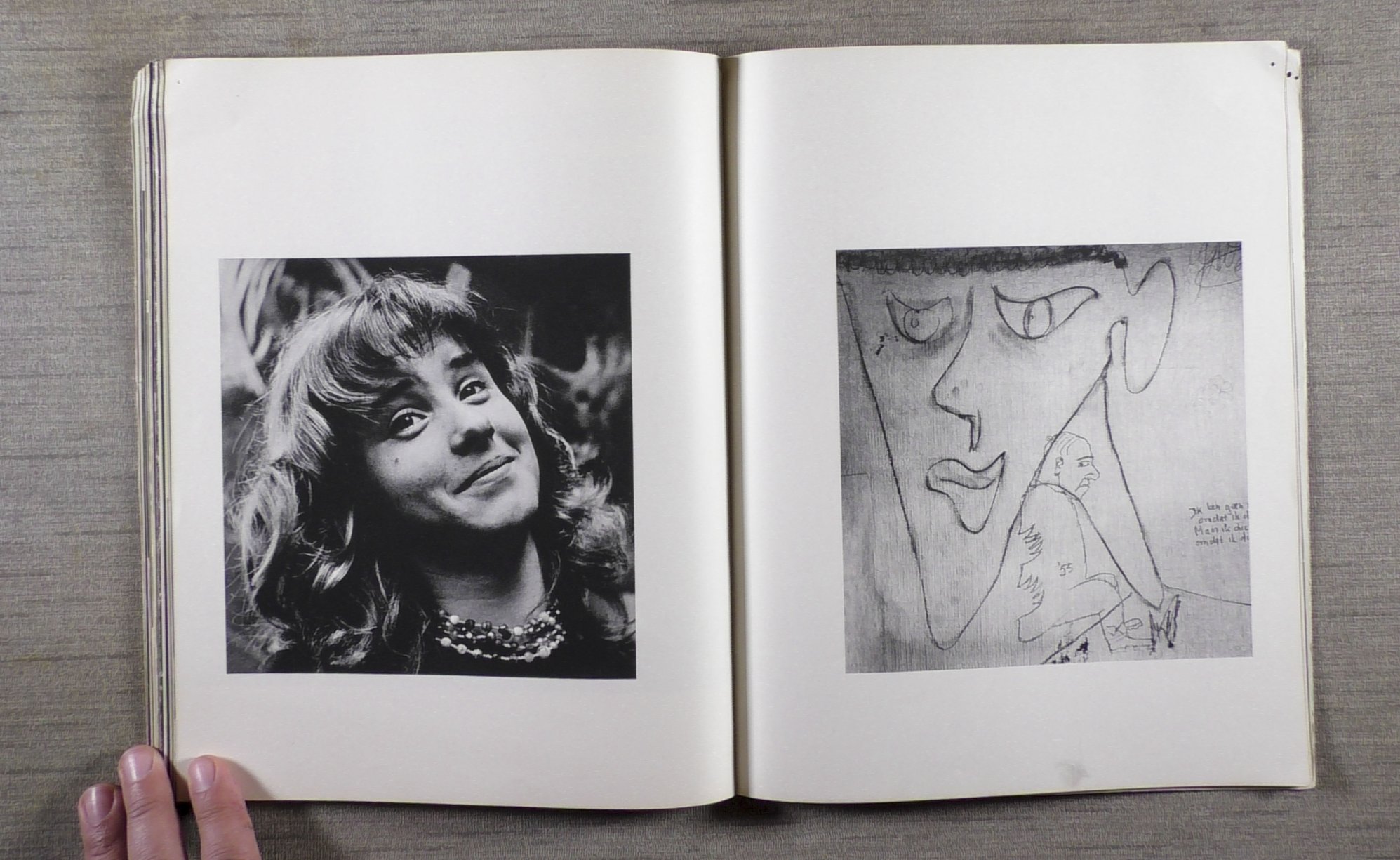

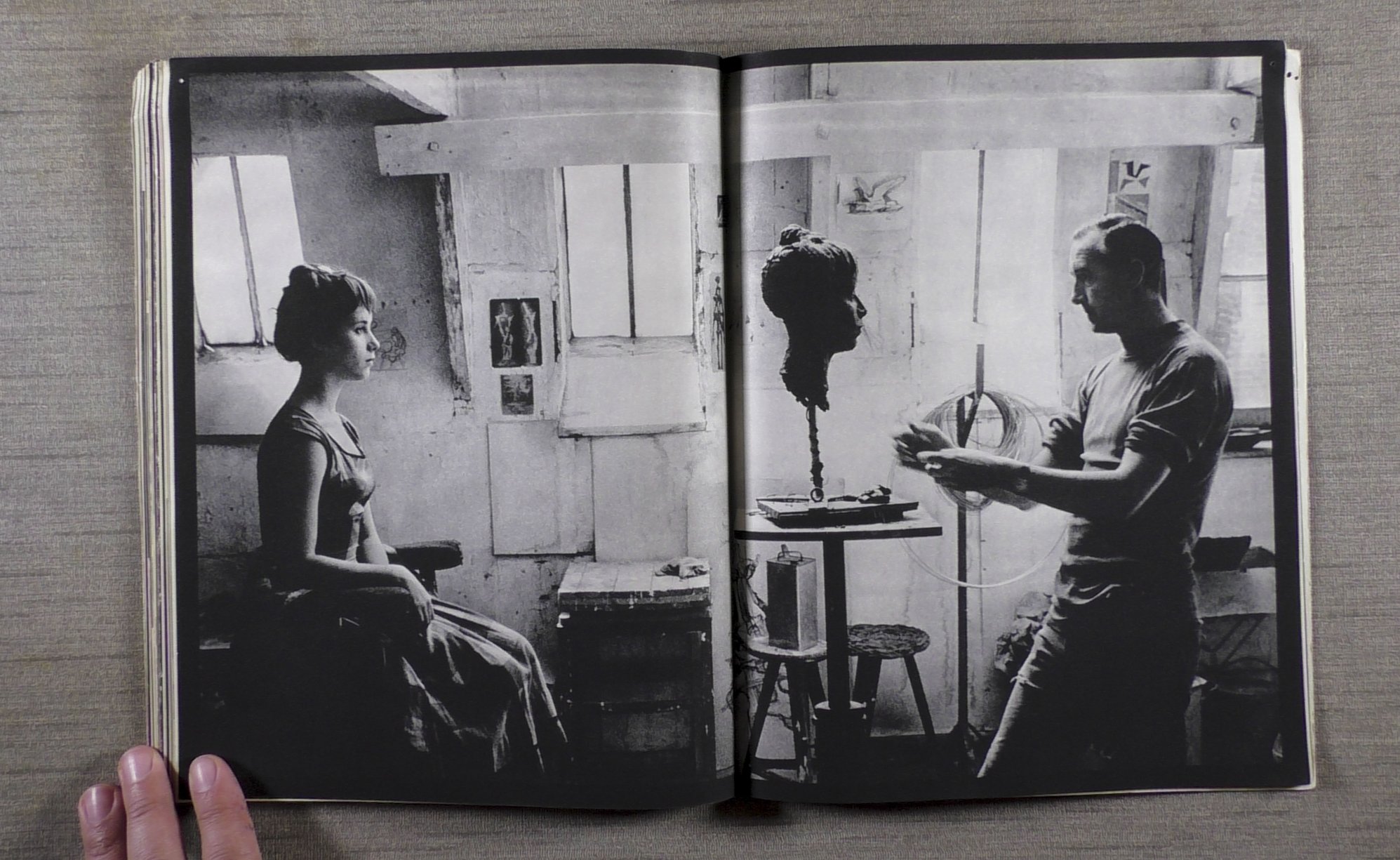

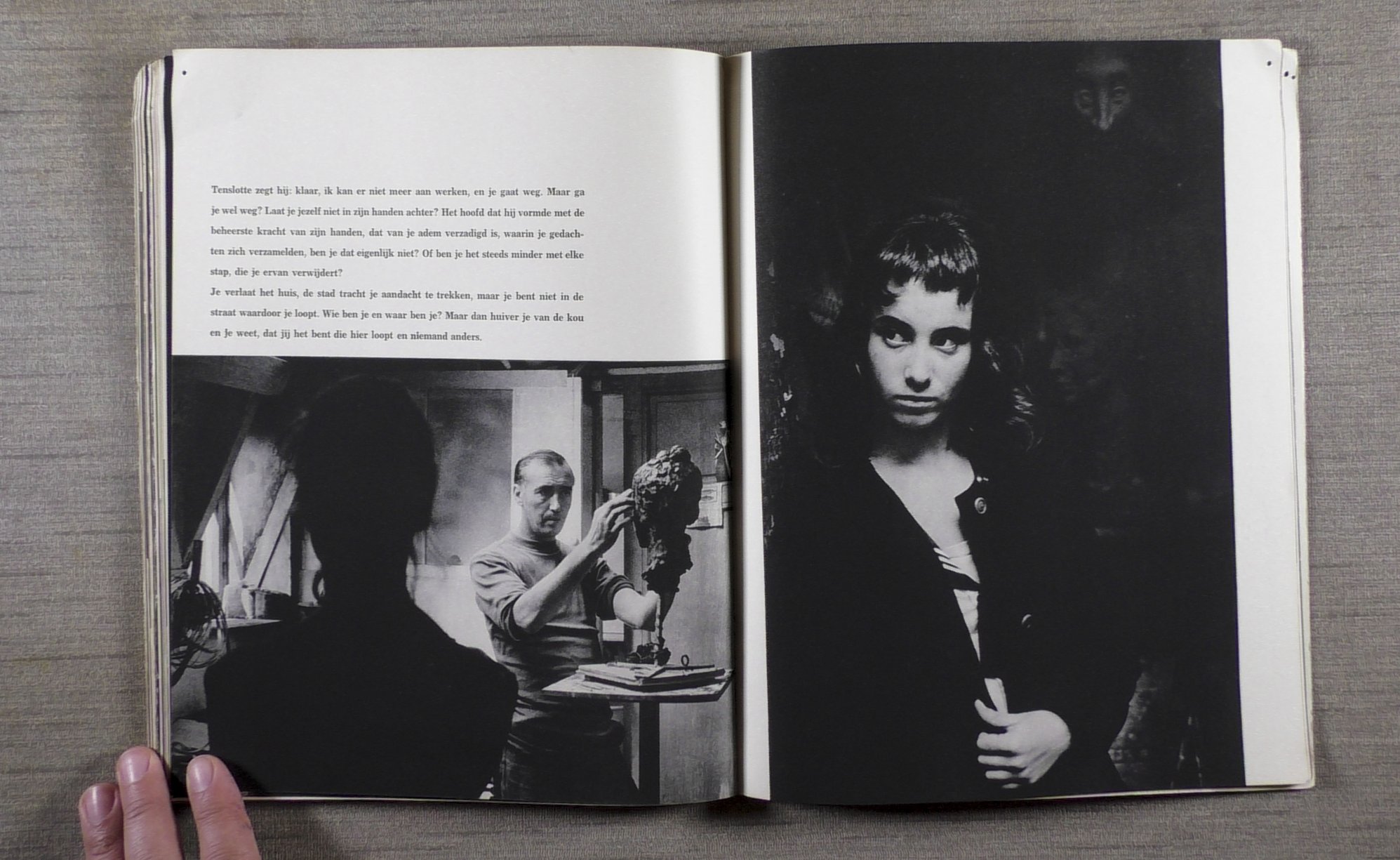

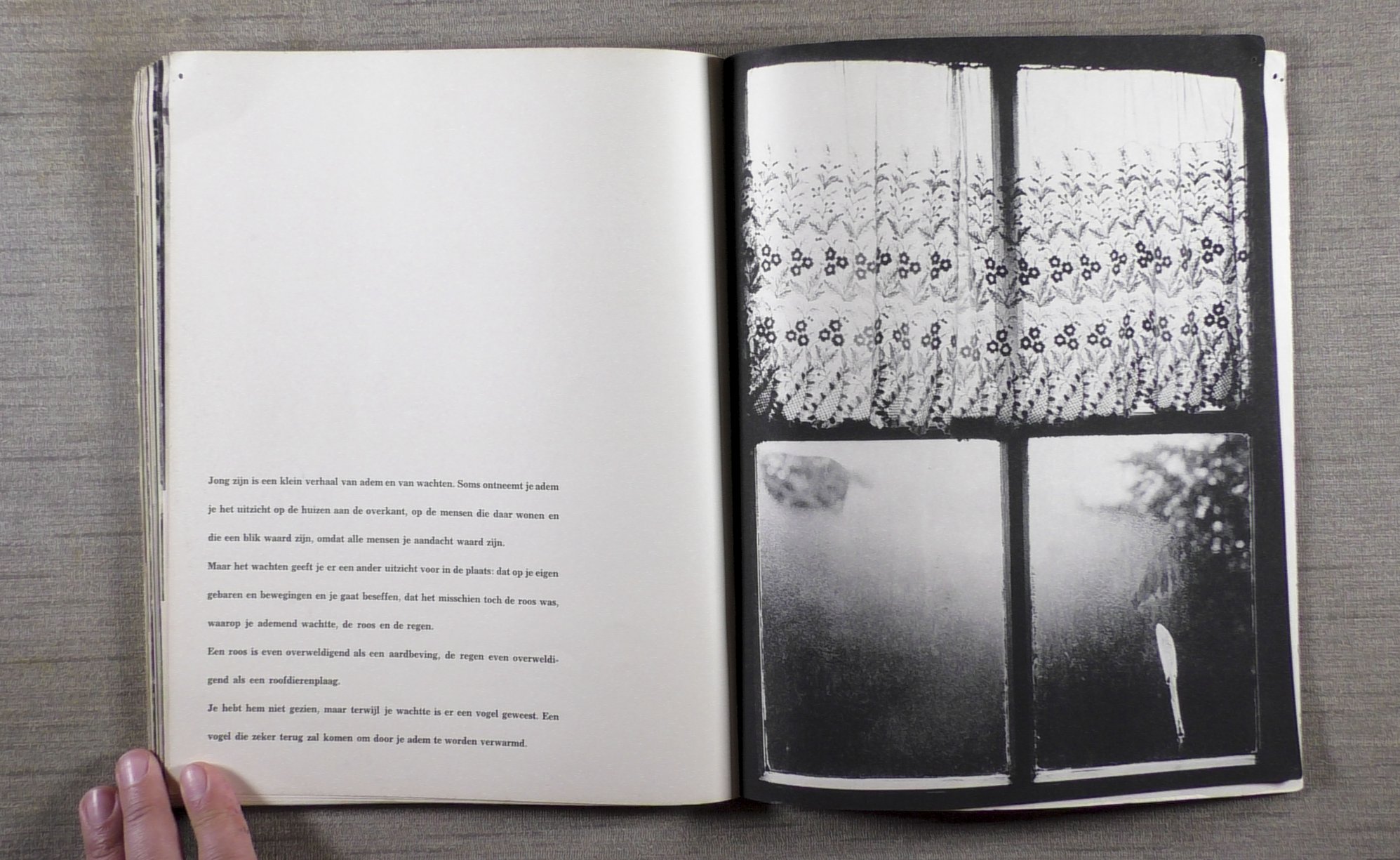

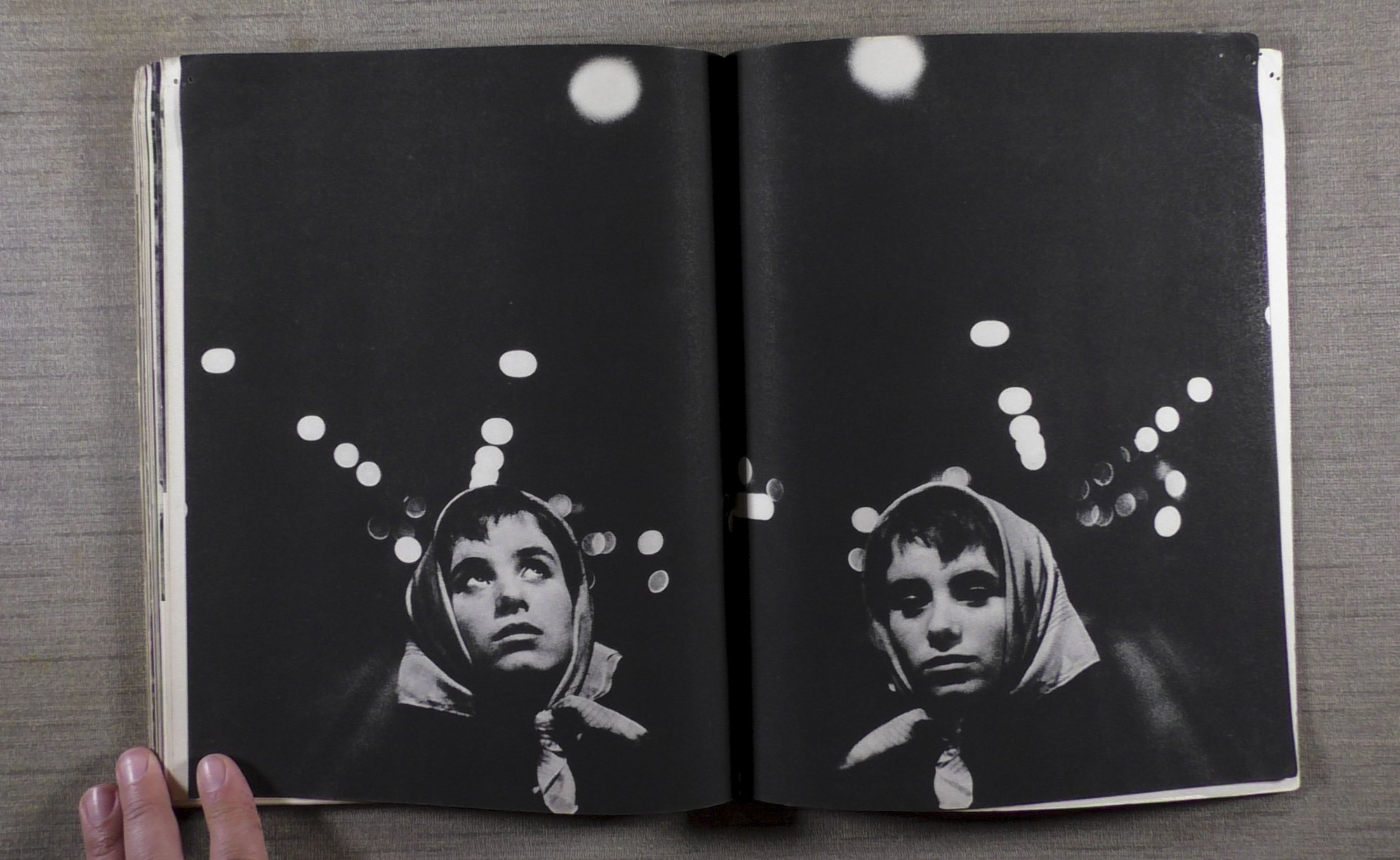

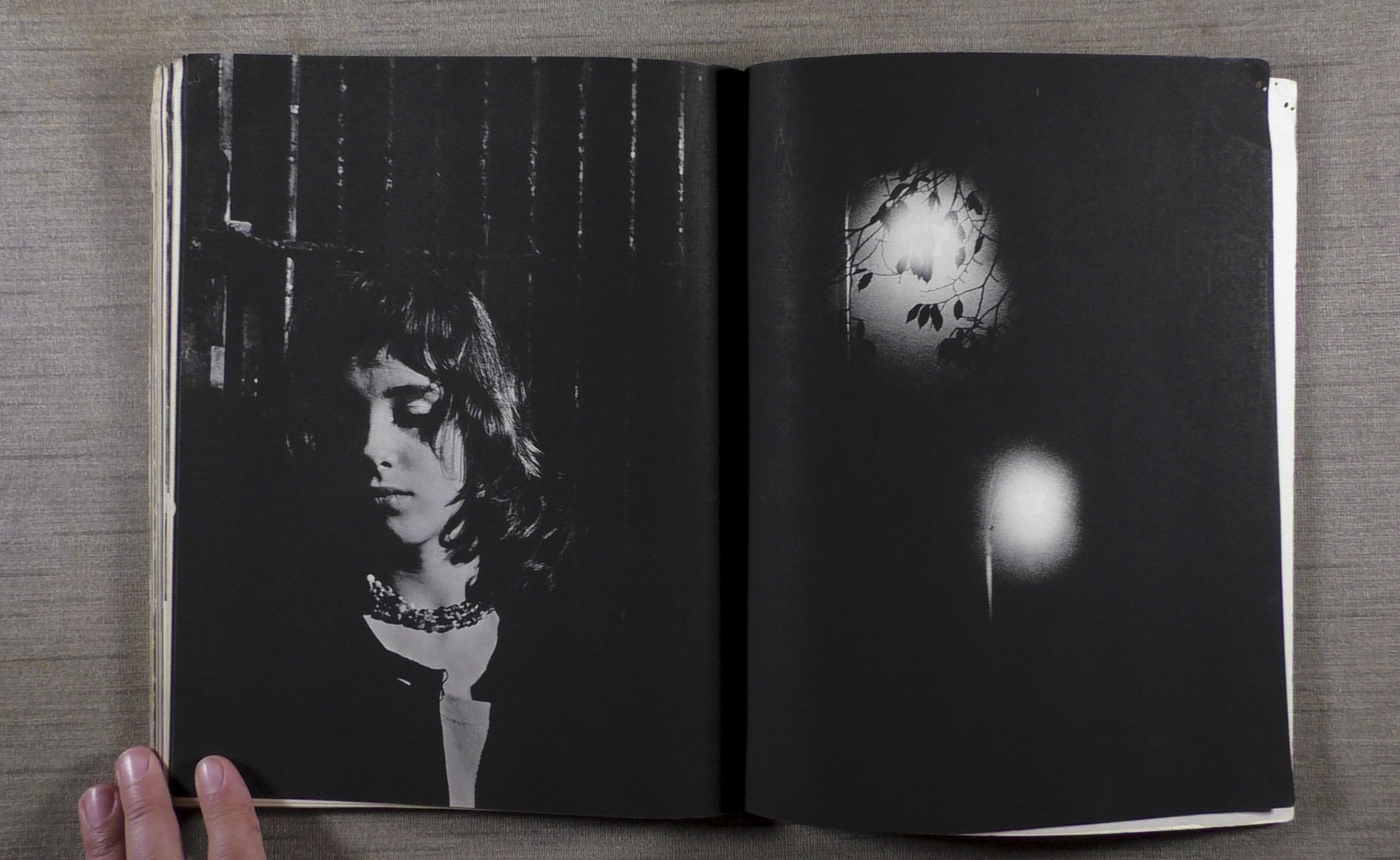

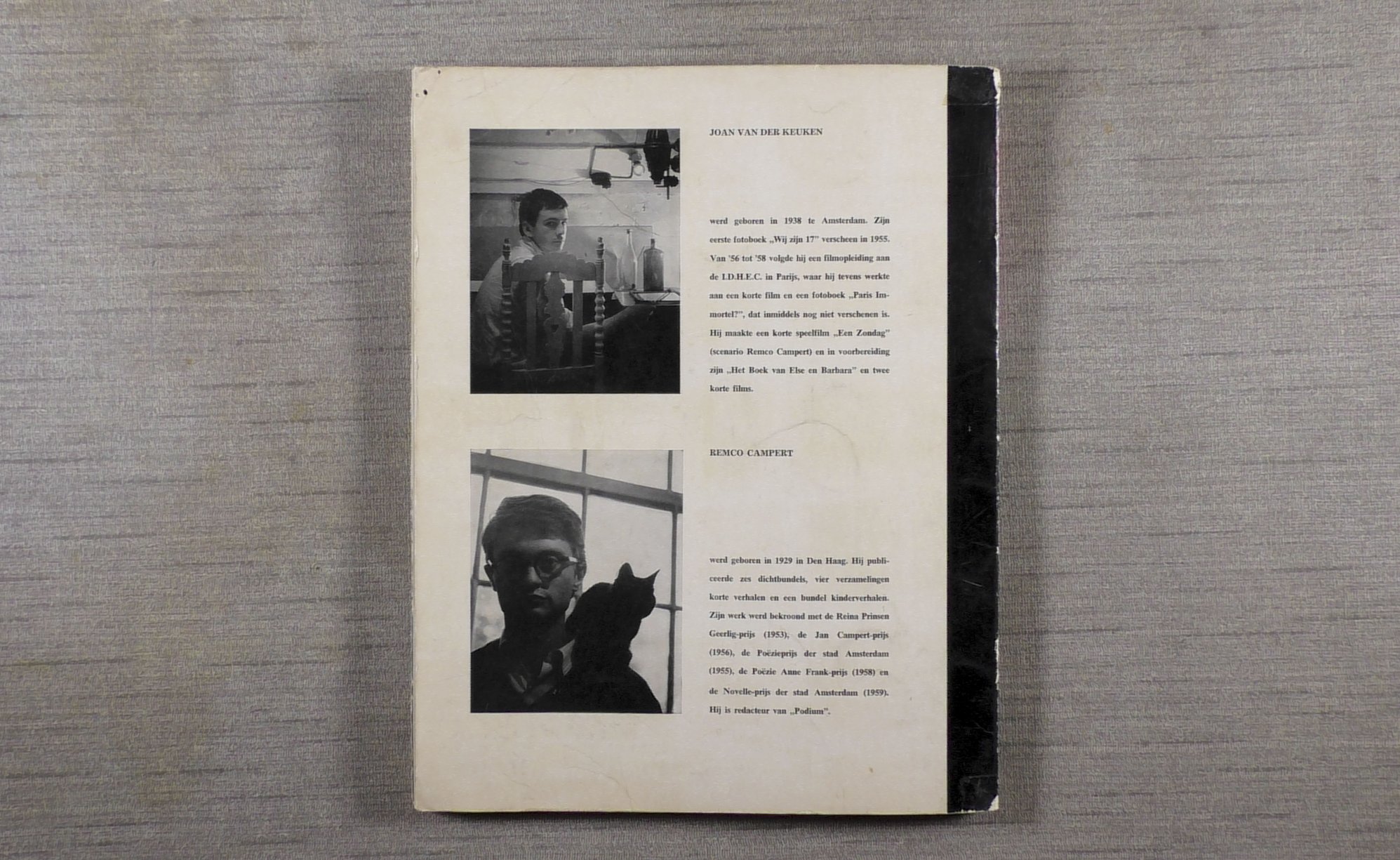

One of my earliest memories of being immersed in art was while drawing in my bedroom while listening to Hatful of Hollow by the Smiths. I was 16 and it would be a very long time before I could channel my moodiness into something worthy of sharing with others. So I’m a little jealous of prodigies like Joan van der Keuken. He published his first photobook, Wij zijn 17 (We are 17), in 1957 at age 17. But it’s his second book, Achter Glas (Behind Glass), made at the ripe old age of 19, that slays me. I recommend looking at it while listening to The Smiths.

Recently Received: The White Sky by Mimi Plumb

When I received a copy of Mimi Plumb’s new book, The White Sky, I knew absolutely nothing about it. I certainly didn’t know that Plumb was 18 when she made the first photos in 1972. But when I looked at the book, it buzzed in my hands and I knew it was the product of pure immersion. When asked to name my favorite book of the year, this is the text I submitted to PhotoEye:

I should probably offer an astute explication for why The White Sky by Mimi Plumb (Stanley Barker) is my favorite photobook of the year, but my goosebumps don’t respond to logic. This book satisfies me in a deep way, and that’s something I’d rather savor than scrutinize.

But after reading Jim Moore’s essay and reflecting on my adolescent creativity, I decided to dig a little deeper. I reached out to Mimi via iMessage and asked her about her early work:

I began photographing in high school, when I was 15 or 16. I was living at home, in the suburbs of San Francisco in the town of Walnut Creek. My brother was at UC Berkeley and he got me involved in photography. He showed me the darkroom and taught me how to print. I remember really enjoying the process as opposed to writing poetry, which was somewhat tortuous and agonizing for me. I try to keep that element of having fun when I make pictures, even if what I’m photographing is dark and disturbing. Fun meaning the process of making the photographs feels alive with possibility.

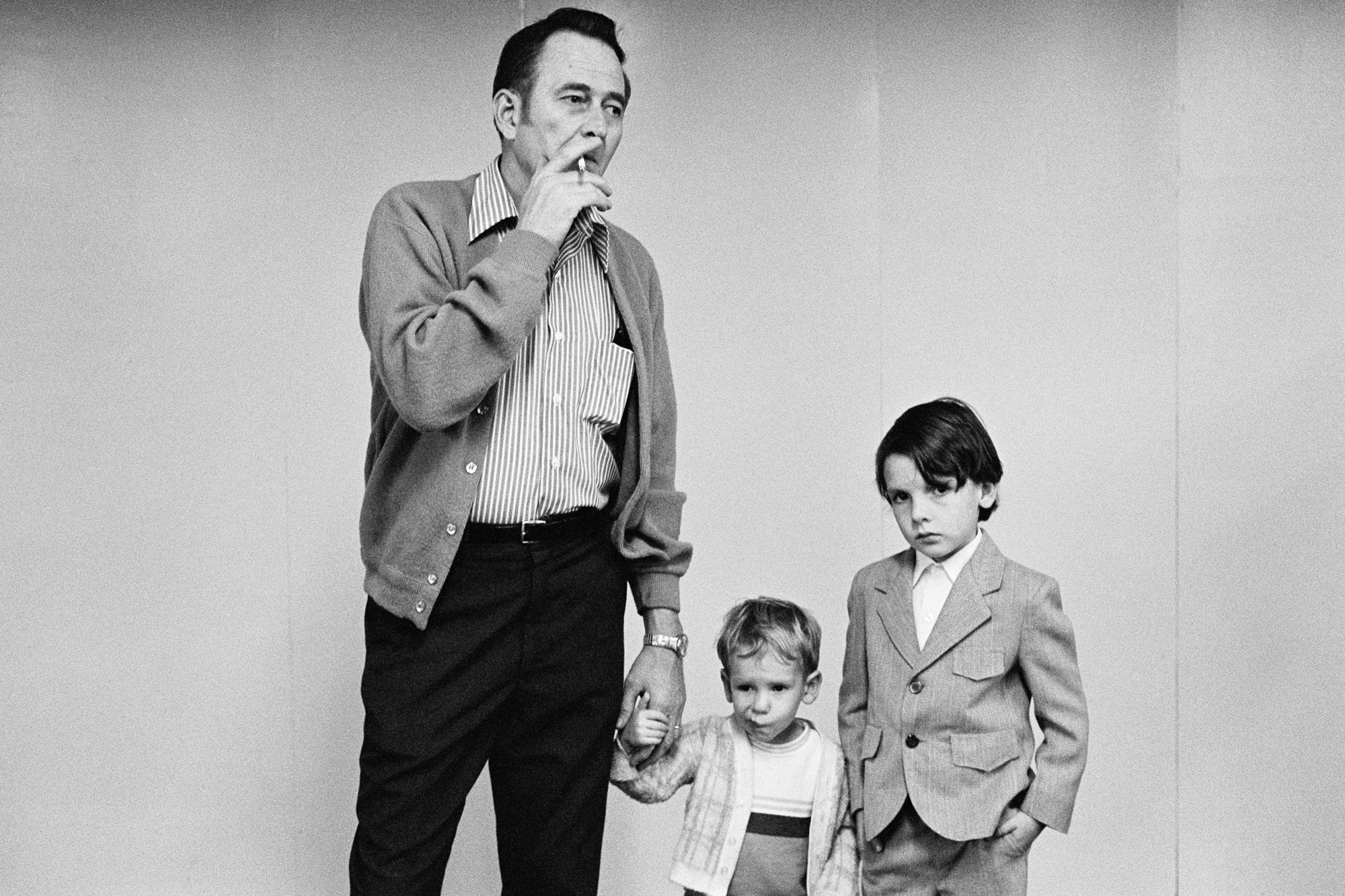

I remember making the picture of the father and two boys at the Ringling Bros circus. I think I made some of my strongest photographs ever that night. I was 18 then, and it was about a month before I started photography classes at the San Francisco Art Institute.

This is painful to say but I made that picture before I had seen Diane Arbus’s work, and then I stopped making that type of picture. I kept thinking I couldn’t do anything that could equal her work and her vision.

It was easier to make pictures when I was younger, there was less noise in my head. I taught for 30 years, and I often thought the photographs made by my beginning students were more interesting than the work of my advanced students.

Visit Mimi Plumb’s website

Purchase The White Sky HERE

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Refresh the Map

Early November. Inevitably world-time shatters all over again, and with it the ability to write stories splinters, and paragraphs fall away and then sentences, forget it. It’s not that things themselves were okay (they were not), but for a time you had found an okay way to be with them. But now it is the days leading up to and then it is the day of and the day after and the week of. People you know start casually asking things like, what is your plan for the coup.

You do not have a plan for the coup. At least, all you have to do is drive, pretty much, across a broken country. You have been working 2,500 miles away, writing and scattering food for birds and drifter wild animals. You have been steeling yourself not so much for these weeks as for the longer, after. Maybe something in you was not quite ready to consider what it would mean to enter another purgatorial warp. But now you are inside it again.

New York again eventually. But you don’t even have a route. That part at least is by design. Every morning, decide the itinerary. There is time usually for one or two stops, to remind yourself where you are — to escape somewhere off the trail of vile handmade signs on the highways.

But there are also days when find yourself in a motel fugue. Different town, different layered curtains, different wall art, different day, in theory. Sanitize the lamps, wipe down the remote control, MSNBC nights, MSNBC mornings. One night the Georgia numbers are exactly what the Pennsylvania numbers were that morning. 49.4% to 49.3% and for a moment you cannot remember traveling any miles in between them. Refresh the maps.

Not only are you suddenly not writing stories, but it again becomes hard to read whole chapters. A dangerous symptom that demands an instant remedy, a restart. Falling asleep with something lodged in your brain other than jigsaw shapes of morphing reds and blues.

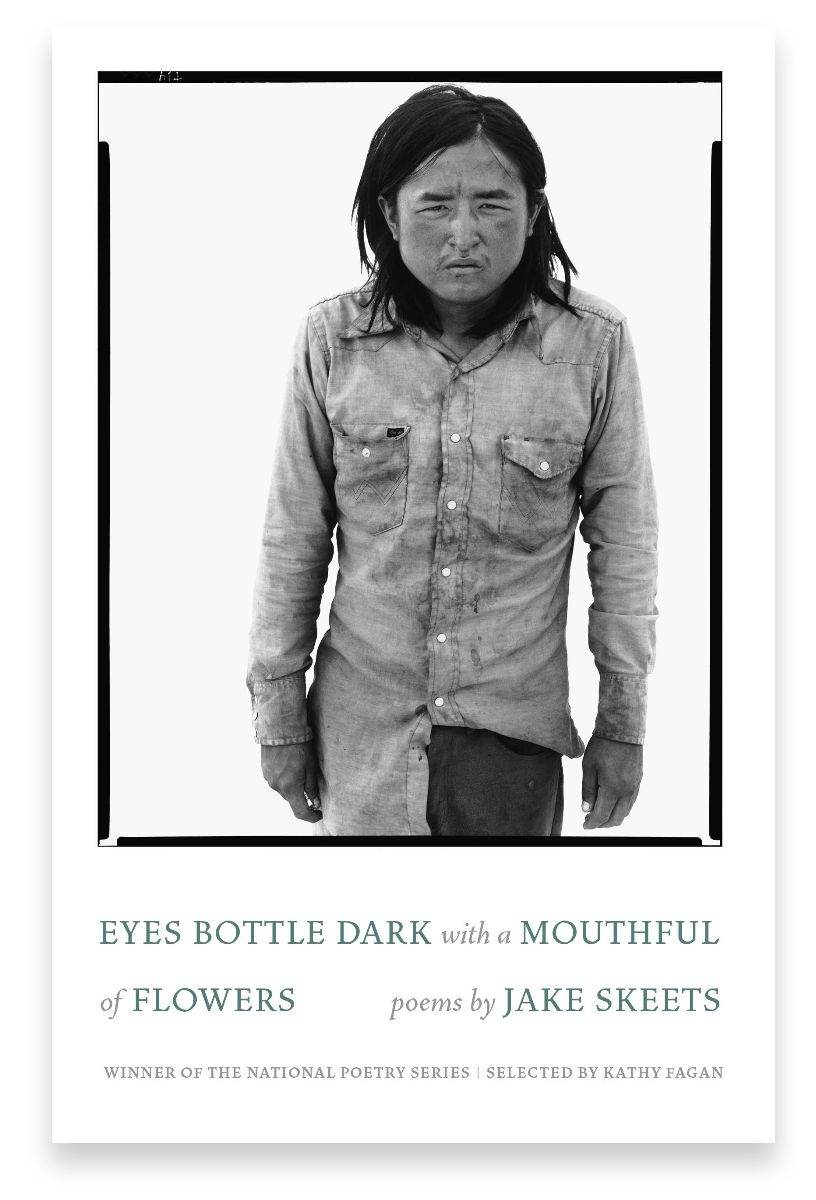

So begin, as you often do when stuck, with just a phrase, a line, a verse. Not for the solace of what is in the words, but for the fact of the words themselves. Read for the sheer startle and pleasure of language. A rhythm in your head. The last book recommended to you is called Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, by the poet Jake Skeets. Not sure how you could have missed it — it’s been given many, deserved honors — but there it is. Flip it open at random, land on this line:

Has the evening for a face.

II.

In an interview with the poet Kathy Fagan, who selected Skeets’s collection as the winner of the National Poetry Series, Skeets talks about working into his poems the idea and actuality of a chiasmus — words repeated in reverse order. Born in Vanderwagen, New Mexico, Skeets is Diné (Navajo), specifically Black Streak Wood, born for Water’s Edge. He explains a chiasmus like this:

In one my favorite lines from one of my favorite poems, Tapahonso writes “the store is where I’m going.” In English, the correct subject-verb-object structure of the sentence would be “I am going to the store.” However, Diné follows an object-subject-verb structure and that’s why the line reads “the store is where I’m going.” So when Diné and English are paired, it creates a chiastic read: “I am going to the store / The store is where I am going.”

The title Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers is its own chiasmus. “If I stare long enough, I see my uncle in a mirror. The bottles we use for eyes,” Skeets writes in its opening poem “Drunktown.” He builds chiastic structures, mirrors of language, everywhere in the poems — in its clashing, merging themes of queerness and masculinity, in the expressions of love and violence between men (“You kissed a man the way I do / but with a handgun”), in the beauty and extraction of the coal-, copper-, uranium-rich land of the Navajo Nation, eros and erosion,where men are “returned to smolder” (“eye bottle dark / mouth stuffed with cholla flower” and “an eye alters into alternator / the other a hubcap” and “His veins burst oil / elk black” ), in the imaginative and geographic world of the book, Na’nízhoozhí, in English: Gallup. Skeets cites both its nickname (Indian Eden) and its slur:

Drunktown.Drunk is the punch. Town a gasp.

In between the letters are the boots crushing tumbleweeds,

a tractor tire backing over a man’s skull.

Skeets’s poems are full of flower and dust, railroads and skin, headlights and soil, clouds and thunder, rapidly changing colors of sky. Here’s another chiasmus: “Storm” has come to read as a metaphor foreshadowing danger, chaos, darkness to a culture whose primary relationship to land is conquering and taming. “However, for Diné and the many tribes of this area, a coming storm means, quite literally, life,” Skeets tells Fagan. “The rains provide for the crops. This type of recognition and reverence continues today for many communities. Land evolves into time and even discipline.” He continues: “A solar eclipse is another example. While Twitter celebrates a visible solar eclipse, most families here fast and stay inside to respect the ceremony of the cosmos.”

White space enters the book, again and again, eclipsing the pages or separating them completely. Talking elsewhere of his poems Skeets compares an empty page to a field.

III.

Try to get back to that field. The empty page is also a backdrop. You (you-me, and the you reading this) recognize the cover image of Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Dark.

By the time Richard Avedon sent a signed copy of In the American West (1985) to a man he’d photographed in 1979, whose occupation he’d captioned simply as Drifter, five years had passed. Drifter had a name, Benson James. Benson James had a family, who wrote Avedon to tell him that their brother/cousin/uncle/son had died four years earlier. Years later, coming across the book, his nephew briefly wondered about the picture of this unknown man squinting intensely at the camera, hair grazing his hunched shoulders, one shirttail swept up, against the blank backdrop. The image, unexplained, and the whiteness that surrounded the figure of this lost relative, stuck in his memory. Has the evening for a face.

When Skeets grew up and began this book, he writes in this essay, “The portrait of my uncle found a whisper of itself in almost every page.” You, who have imagined lives from scraps of found photographs, understand this, how details change and maybe even become embellished (“stab my uncle forty-seven times behind a liquor store”), how a story has to become untethered in order to free itself. When a “real” number is “more than twenty times” (as Skeets writes in the same essay), does it matter anyway?

“As I look at the portrait now, it seems my uncle is still trying to replace what was made invisible in or stolen from his portrait with only his body. With his physical presence he is holding onto the remnants of story, beauty, and chaos in a space made to appear empty. My book is trying to do the same thing and it is only fitting that his portrait preface the book.”

The portrait of Benson James, Drifter, is a kind of chiasmus too. His picture originally appeared alongside blank-backdropped images of truckers, rattlesnake skinners, lumber salesmen, a cowboy movie start president. “I do not want to exploit my uncle’s portrait,” Skeets writes. “I also do not want to attack Richard Avedon. That is not the project with this book-cover choice. I simply aim to give back what was taken, a repatriation of existence through language.”

IV.

One of the tricks of these poems is that they merge to form a kind of story. But at their core they are also built from the kind of play

in language that is especially important when starting and when starting over. Within them is a mash of memory, of overheard talk, of imagined transcribed 911 calls, imagined transcribed police scanner speak, scraps from old magazines and newspapers, acknowledged lines from other poets, a list of all the famous people who once slept at the hotel blocks from where Skeets’s uncle was killed.

Maybe it’s meant that, at first, you are only able to take them in, piece by piece. This kind of reading — which is more akin to listening, really, for the sound of the words — has helped you trigger other restarts before. Refresh the map, the reds and the blues, and the pale tinted states, the ruptures visible but moving. At the end of the night throw your stupid phone inside the book, in hopes it will absorb the words.

The Lunch Table

Ethan: Forged in Fire is currently my favorite ridiculous competition show to watch. 6/10

Tash: If you need to escape into a world where the greatest challenge in life is finding the hottest party – Everybody Wants Some!! is the movie for you. The unofficial sequel to the iconic 1993 Dazed and Confused will leave you wondering where everybody’s masks are and why everyone is drinking out of the same red solo cup. 8/10

Alec: I signed up for the Mubi streaming service just so I could watch the film Dawson City: Frozen Time. It was worth it. 9/10

Lastly, Little Brown Mushroom has a book sale until the end of November HERE. I’d love to send you a postcard.