In this newsletter:

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Gone Fishing

- Ex-Libris: True Stories by David Byrne, with photos by William Eggleston

- Recently Received: Encampment, Wyoming. Selections for the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948

- The Lunch Table

Last December the poet Elaine Bleakney sent the following email to some friends:

Hello! It’s my 45th birthday this Friday and I’ve been thinking about chance moments of kindness with strangers. I miss these. I miss the kind of travel filled with these.

I’m wondering if you would like to join me in making something this Friday.

The idea is: buy a flower or flowers and hand them to a receptive masked stranger. Look them in the eye and smile behind your mask. Bask in their surprise and (hopefully) delight. That’s it. If you are feeling uneasy about the viral (!) nature of all this, go ahead and leave flowers on the dash of someone’s car, at a doorstep, in a mailbox — you get the idea.

If you take a picture and/or write to me a little bit about your flower gift to a stranger, I’ll collect it with all the ones I receive and send the collection of flowers back to you on New Year’s Eve.

I knew that getting out the door and doing this assignment might relieve my year-end blues, but I couldn’t muster the spirit. It didn’t help that I had a depressing birthday of my own around the same time.

When I emailed Elaine in January to apologize, she told me not to worry about it. “My birthday was exceptionally awful as well,” she replied.

This moment of shared unhappiness cracked something open in me. The next day I bought some flowers and gave them to a stranger named Ashton in St. Paul. It was the best experience I’d had in a long time.

Sharing grief and joy is what art is all about for me, but sometimes I can’t manage to do the work alone. For the last year, my partner with this newsletter has been the fantastic writer Rebecca Bengal. Rebecca is my dream collaborator. Her enthusiasm for creative expression is boundless, and her own creative expression is revelatory. But after a dozen Cosmic Fishing trips, Rebecca is off to work on a couple of books and pursue new galaxies. I encourage you to keep following her at www.rebeccabengal.net

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Gone Fishing

When I moved to Texas in the early aughts, I was young and new and not well traveled and found it all disorienting and exciting. Austin was smallish then and in the awkward first stages of tech and startup boom, but gratefully (in some ways and some ways not) still hitched to its seventies and eighties past and beyond. A new friend invited me to a rattlesnake sacking contest. The musician Roky Erickson was still listed in the phone book. One of the first apartments I tried to rent had allegedly been a crash pad for a few members of Willie Nelson’s band, with peeling skyline wallpaper and smoke burns in the carpet. I ended up living longest in a renovated stable around the corner from a faded strip of blues bars, some gone, some reviving, one where I was pretty enchanted to discover you could rent a locker for your liquor. (This was my introduction to the concept of a set-up; the sold only mixers and beer, all else was BYOB.)

And I wanted to understand the particular feeling of the state — the cultural forces below the surface, so different even for someone from rural North Carolina. Movies did that for me at first especially, no matter what category of fiction or purported truth they belonged to. Austin still operated on the glacial pace of Slackers, days in which action moved from porch to porch. Hands on a Hard Body, a documentary chronicling a endurance test in the town of Longview where the contestants must keep one hand on the prize (a brand-new truck) at all times — a film of delirious breakdowns, and the deeply ingrained Texan love of trucks. True Stories, David Byrne’s only fictional film, so not “true” in a documentary sense, but is, in a larger sense (as a writer who flits between worlds of fiction and nonfiction, I borrowed its name for a creative writing seminar I taught and my Instagram handle, both a kind of inside joke and a source of confusion for literal-minded followers). It’s set in the imaginary town of Virgil, Texas, a cast of outsized characters and tales inspired by tabloid headlines, a 1980s Texas Instruments world that forecast the one I’d moved into but also summoned the spirit of a giant state that, in its ideal incarnation, has room for millions of individuals and the capacity to tolerate and appreciate them all. “Everybody has tones,” Ramon (Tito Larriva) confides to a coworker on a factory assembly line. “Like a radio station. It’s the music of your soul.” There was Paris, Texas; a lot of Les Blank; on and on. These were among several films that I looked to almost like travel guides, a way of navigating the psychic geography of the state. Also, many of them operated outside or on the edges of standard narrative conventions, which hooked me too.

Recently I had a similar feeling when I finally saw Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, a year after its pre-pandemic premiere at Sundance. I’m glad I missed it then, because it strikes so differently now. In their first full-length, 45365 (2009), filmmaker brothers Turner and Bill Ross went back to the zipcode of their Ohio birthplace — a film that turns a town into a story. Several more films in, they tighten that focus to contain just a day and night in the life of a Las Vegas strip mall bar called the Roaring 20s on its last night ever: the bar is the story. Seen now, the film is a portal to another lifetime, depicting a night at such a place with remarkably eerie verisimilitude, excruciating and banal and tense and beautiful and epiphanic.

There’s a lineage of course. As much as Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets is in the canon of Cassavetes, and Varda’s L.A. movies, and a side of Les Blank, it’s also very much in the canon of bar films and shows as mainstream as Cheers and as singular as William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton, a nightlife verité among the Memphis demi-monde, and novels of wise and erudite and soused raconteurs from Malcolm Lowry on to Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree. It is populated by archetypes, outsize performers and soliloquists (every oracle in a bar worth his salt, whether Randall of Canton or the alcoholic philosopher Charlie in Joy Williams’s novel Breaking and Entering, or dozens of real-lifers, is given to quoting Shakespeare). The soundtrack leans on Las Vegas tropes — Buck Owens’ “Big in Vegas” opens it, Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler” plays at least twice, sung along to by the denizens of the Roaring 20s both times — and on jukebox standards, Michael Jackson, and other dive bar lonelyhearts patron saints Patsy Cline and Roy Orbison. When the day bartender takes out his guitar and sings “Cryin’,” the bar already looks midnight drunk, and the camera catches the reflection of Michael, an out-of-work actor and alcoholic who crashes nightly on the Roaring 20’s couch, singing the words with him.

In moments like these, or even the bartender grumbling at a TV news story of the closure of the world’s biggest gift shop” (“Fuckin’ Celine Dion can have this town, I’m moving”), I think about these lines from Richard Hugo’s poem “The Milltown Union Bar”:

You could love here, not the lovely goat

in plexiglass nor the elk shot

in the middle of a joke, but honest drunks,

crossed swords above the bar, three men hung

in the bad painting, others riding off

on the phony green horizon. The owner,

Fresh from orphan wars, loves too

but bad as you. He keeps improving things

but can’t cut the bodies down.

Watching it for the first time in January 2021, it also reminds me how much I miss strangers — not just strangers, but the intimacy of strangers, a democracy of strangers, extremely individual and communal at once, a collection of people the random likes of which you’re not apt to find elsewhere outside a laundromat or a bus or some other place you don’t want to linger, and generally never long enough to hear unvarnished and vulnerable truths arise out of a sea of trash talk and Jeopardy watching. Suddenly the balding guy with the scraggly mustache might turn to you and openly describe the feeling of stepping out onto the grass in Las Vegas every morning, or another man, the character Bruce, a sage and lonesome veteran, confessing that this is a place you can come “when no one else wants you.” It’s a bar populated by veterans of several wars, actual ones, and metaphoric, down-and-out trials of life, and equalized by need. And gratefully, in its funny and uglier moments, mostly unromanticized. But walled in, under the forever nighttime tones of Christmas lights and with only a dim slice of outside visible from the barstools, it’s also a little theater where chance and accident and familiarity collide — among the many reasons that bars like this are practically irresistible for writers. A bar is not just a story, but a story you can inhabit, slip in and out of at will.

And here is where my fomo enters: BNEP also exists in the company of several films over the last few years that stand out especially because they each, in separate ways, not only do they experiment with innovative ways to tell stories but they do so in a way that is truly possible only in cinema. They are striking a unique balance of imagination and observation, improvisation and invention, enlisting the people in them as not just actors but collaborative writers working with loosely scripted scenarios. They are taking narrative liberties, reworking time in pairings of sound and image that make me both jealous and excited to see, things that I wish could be duplicated on a page.

Chloé Zhao’s extraordinary dramatic feature The Rider, which premiered at Sundance in 2018, fictionalized the lived story of a Lakota cowboy and horse trainer, and a fellow rider badly wounded in the rodeo. The characters in the film play a version of their actual offscreen selves and lives, with slightly altered storylines. Also debuting in 2018, RaMell Ross’s Hale County This Morning This Evening, later nominated for an Academy Award in Documentary, but which takes radical asks in a title card, “What is the orbit of our dreaming?” in the midst of a lyric, nonlinear portrait of Black life in rural Alabama, seen from within, structured in five orchestral-like movements. Watching it becomes a musical experience, biding and visceral and wholly encompassing. Sometimes I like to think of it as a slowed-down Southern prelude to Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death. Last year came the documentary Time by Garrett Bradley, who I spoke with here, about how she blended with her own contemporary footage the tapes that her protagonist Fox Richardson had made for years: an archive of Fox’s life raising their sons, meant to replace the memory and time stolen from her incarcerated husband, whose freedom she worked for nearly two decades to regain. The music of Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou’s, an Ethiopian pianist and nun who was a prisoner of war under Mussolini, bridges present and past.

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets plays with story and authority admirably too. Categorized for film festivals as documentary, it doesn’t attempt to hide the fact that it’s anything but a traditional one. Its characters are mostly non-actors, but they are cast from other bars to exist as versions of themselves, within loosely outlined scenarios and drinking real-life booze. The strip mall bar in Las Vegas is played by a bar in the filmmakers’ adopted city of New Orleans, the bulk of the action filmed in a marathon eighteen-hour shoot and later edited with B-roll footage of Vegas.

Frederick Wiseman it isn’t, but to call Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets fiction wouldn’t feel right. The Ross brothers have said, and I’m paraphrasing, they make nonbinary films in a binary system, and documentary is “the lesser of two evils.” “We hold these truths to be self-evident” the first title card reads in Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets. Meanwhile, their other brother in cinema but not blood (here’s a great conversation between all three of them), RaMell Ross has chosen the label deliberately. “You use the documentary genre because it’s a space where people are predisposed to truth, which is a great, great entryway into an idea,” RaMell Ross said. “The premise of truth puts viewers in the frame of mind to receive larger truths.” (I wrote a little bit more about this here.) Both Rosses’ films beautifully exploit the immersive and voyeuristic qualities of cinema, but radically bending and manipulating time. How else can you watch a film, even in these theater-less days, for ninety-eight minutes and feel as if you’ve inhabited its setting for twenty-four hours.

A bar is a story with its little and large epiphanies and grand entrances and abrupt and sneaky exits and here is where I slink away for the moment. This column started a little over a year ago in the spirit of play and unseriousness, as a kind of impressionistic and tangential and sometimes diaristic sketchbook. And it was made in conversation with and in profound appreciation for Alec’s wonderful gleanings and writings and mind for so many things of photography and art and poetry, and hovering just outside of them. It was also always meant to be ephemeral — Cosmic Fishing is going fishing elsewhere for now. Thanks for reading, stay tuned, and catch me here in the meantime.

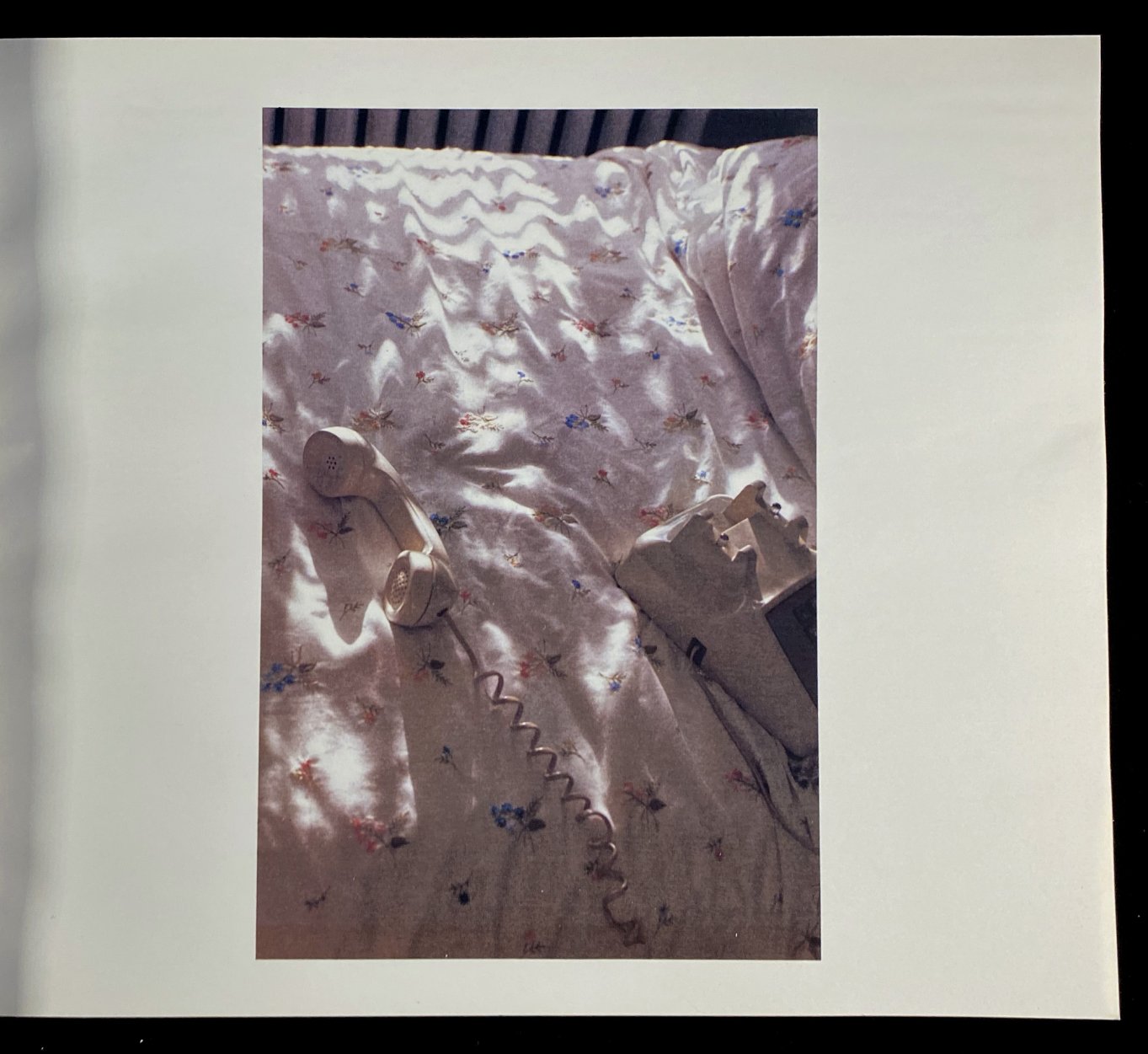

Ex-Libris: True Stories by David Byrne with photos by William Eggleston

Rebecca Bengal’s mention of True Stories prompted to open up my copy of book made for the film. As you would expect from Byrne, it’s less a merchandizing product than a quirky artifact. Byrne writes:

I’m hoping that this book will be the equivalent of the way we experience people and things in their environments. Out there lots of different things are going on at the same time. You can change your focus from one thing to another and still keep the first thing in your mind. You can look through other people’s eyes, or look with a changing point of view, at the same place. You can stand at one spot and focus on different things and really look at them in different ways simultaneously. It’s an effect that sometimes can be achieved in the theater, but it’s almost impossible to do in film. It’s easier in a book.

To achieve these multiple perspectives, Byrne mixed his own photographs with those of Len Jenshel and Mark Lipton. But he reserves a special section at the beginning of the book for another notable photographer:

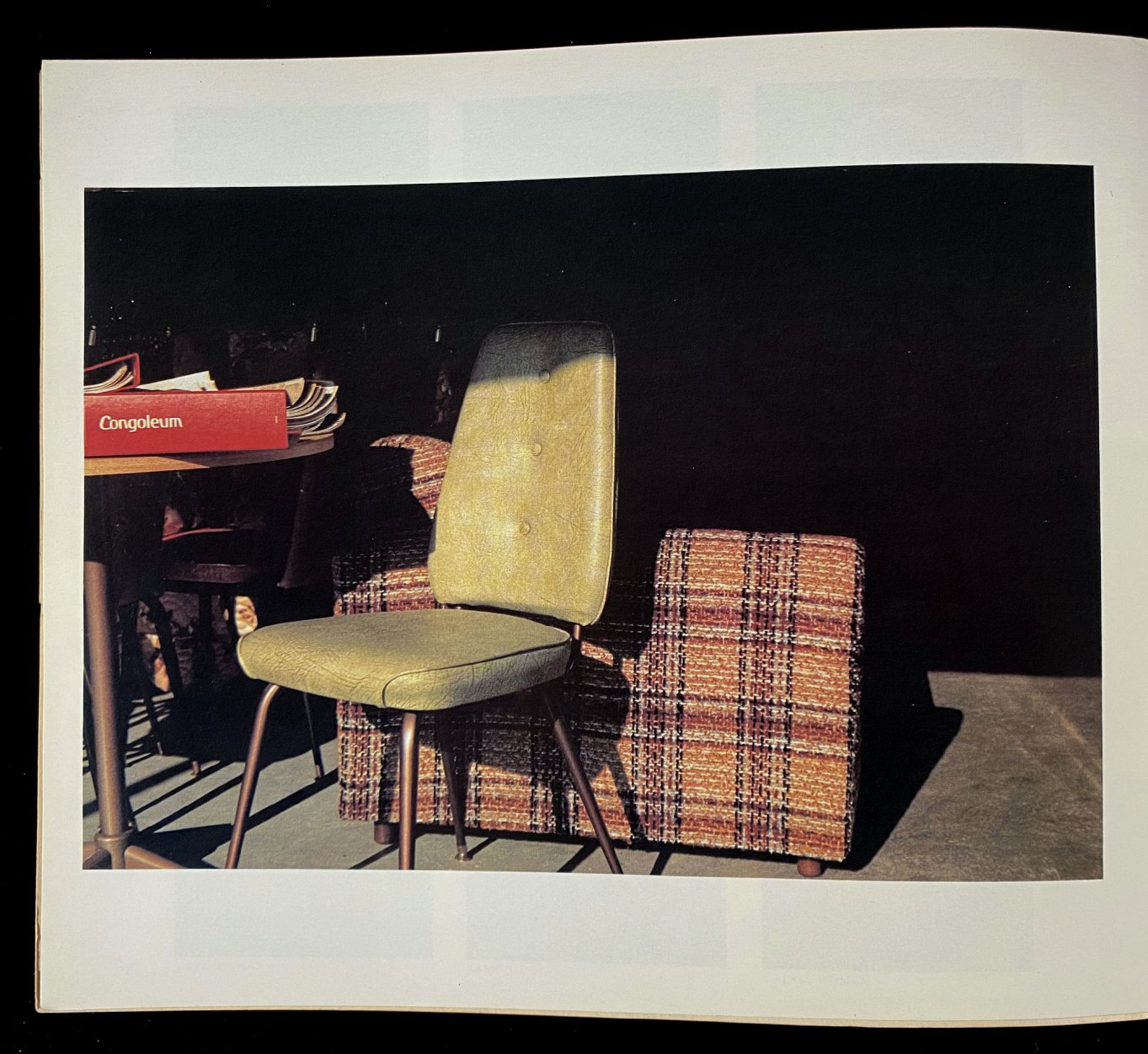

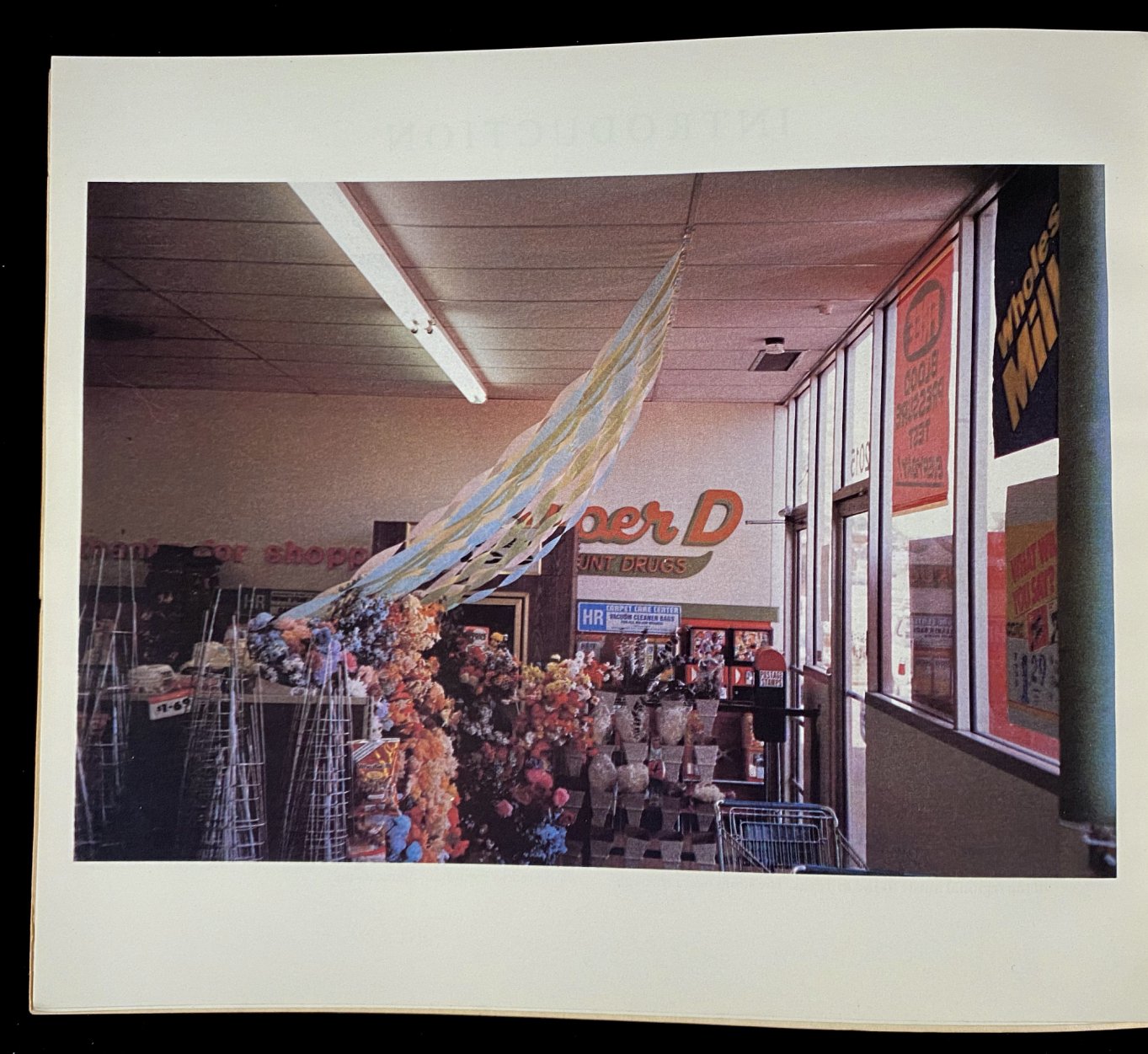

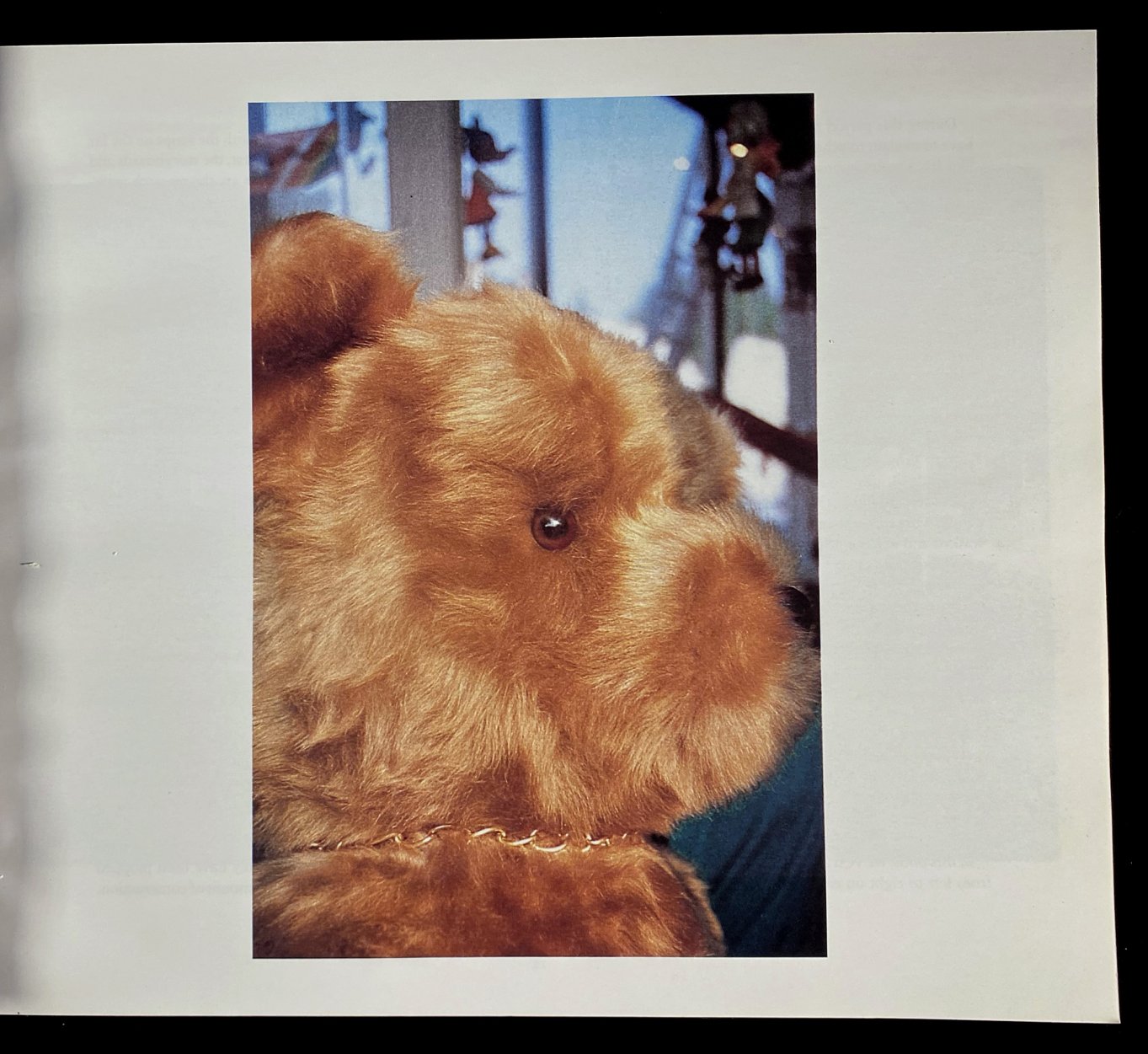

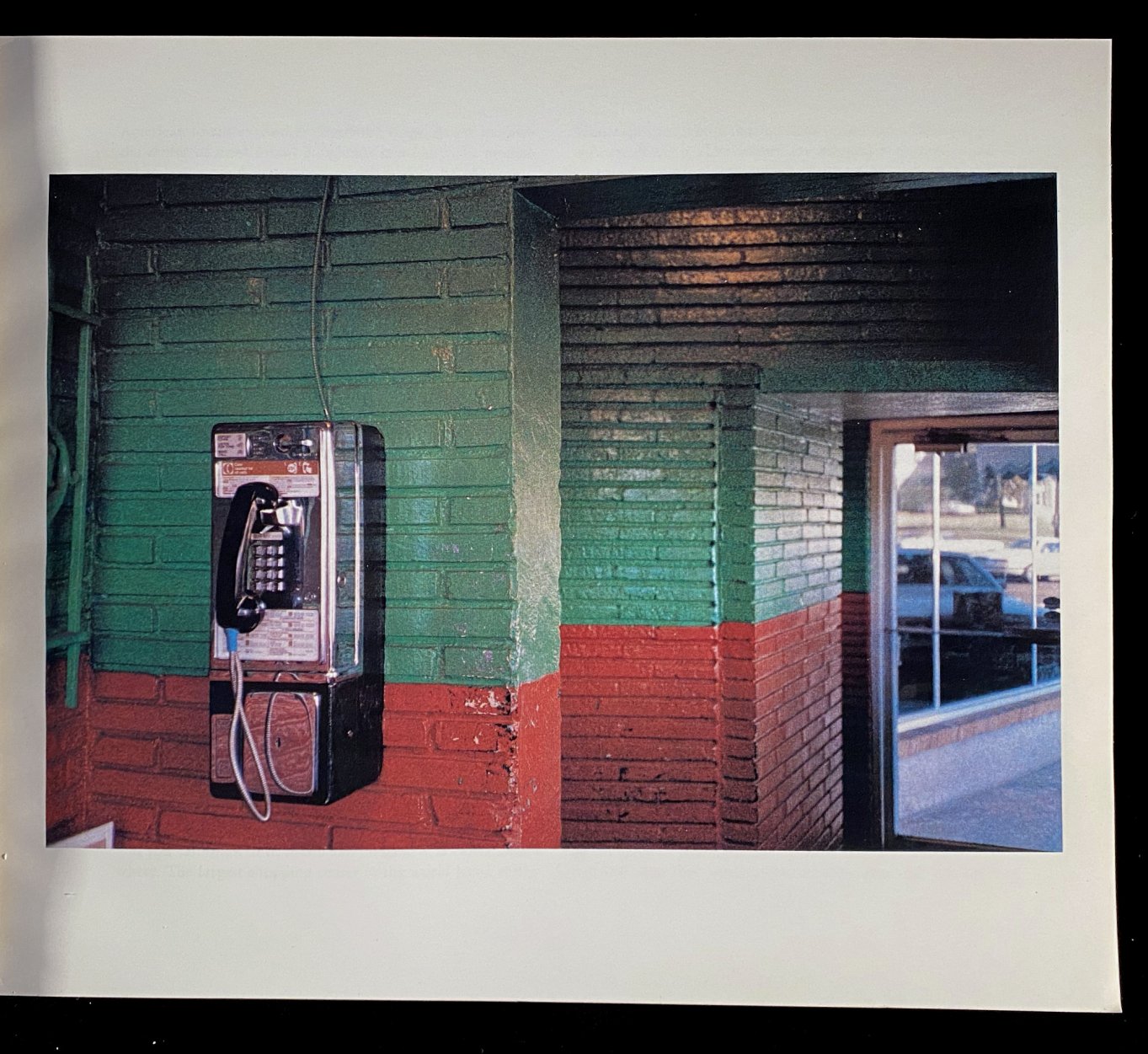

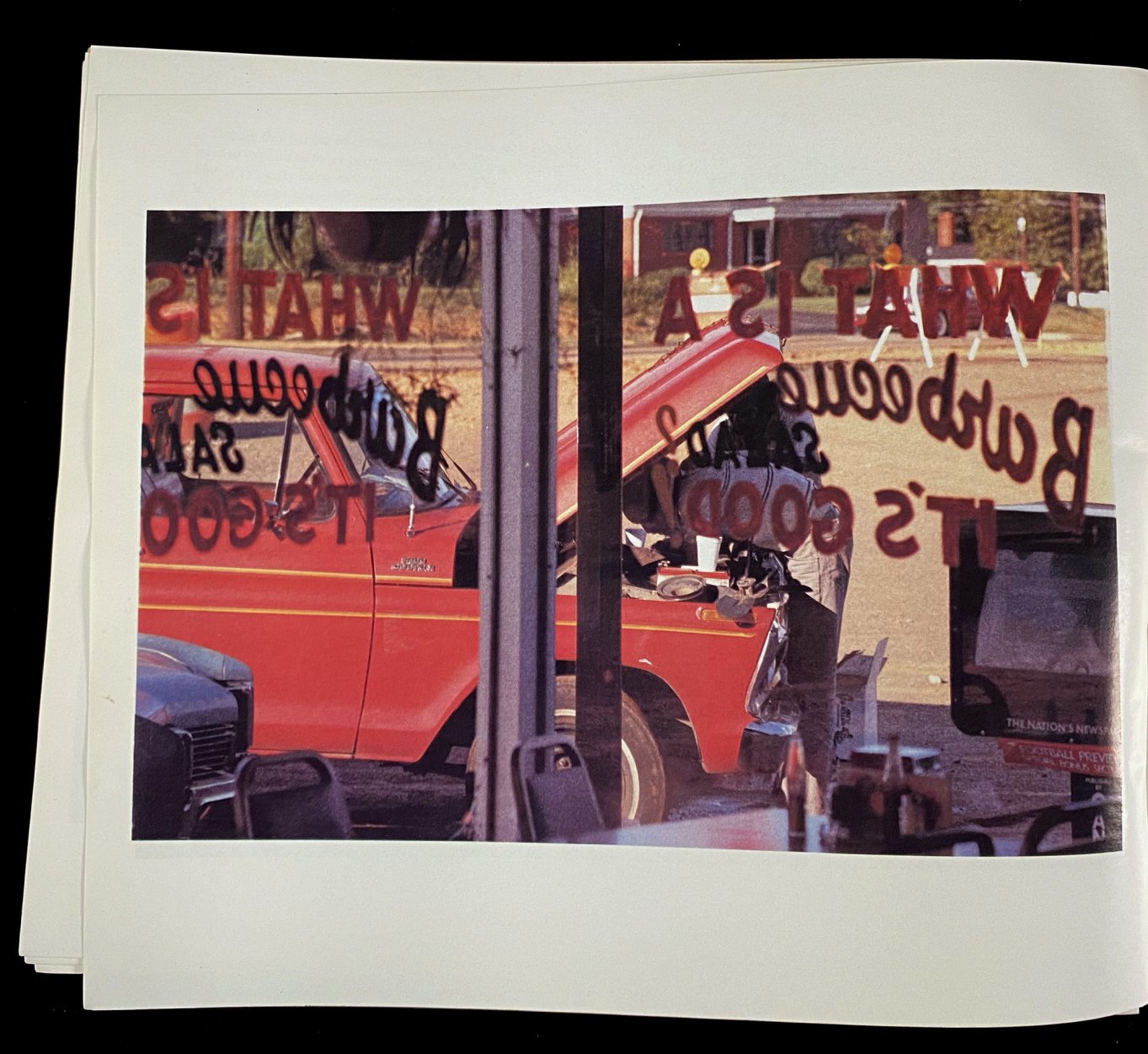

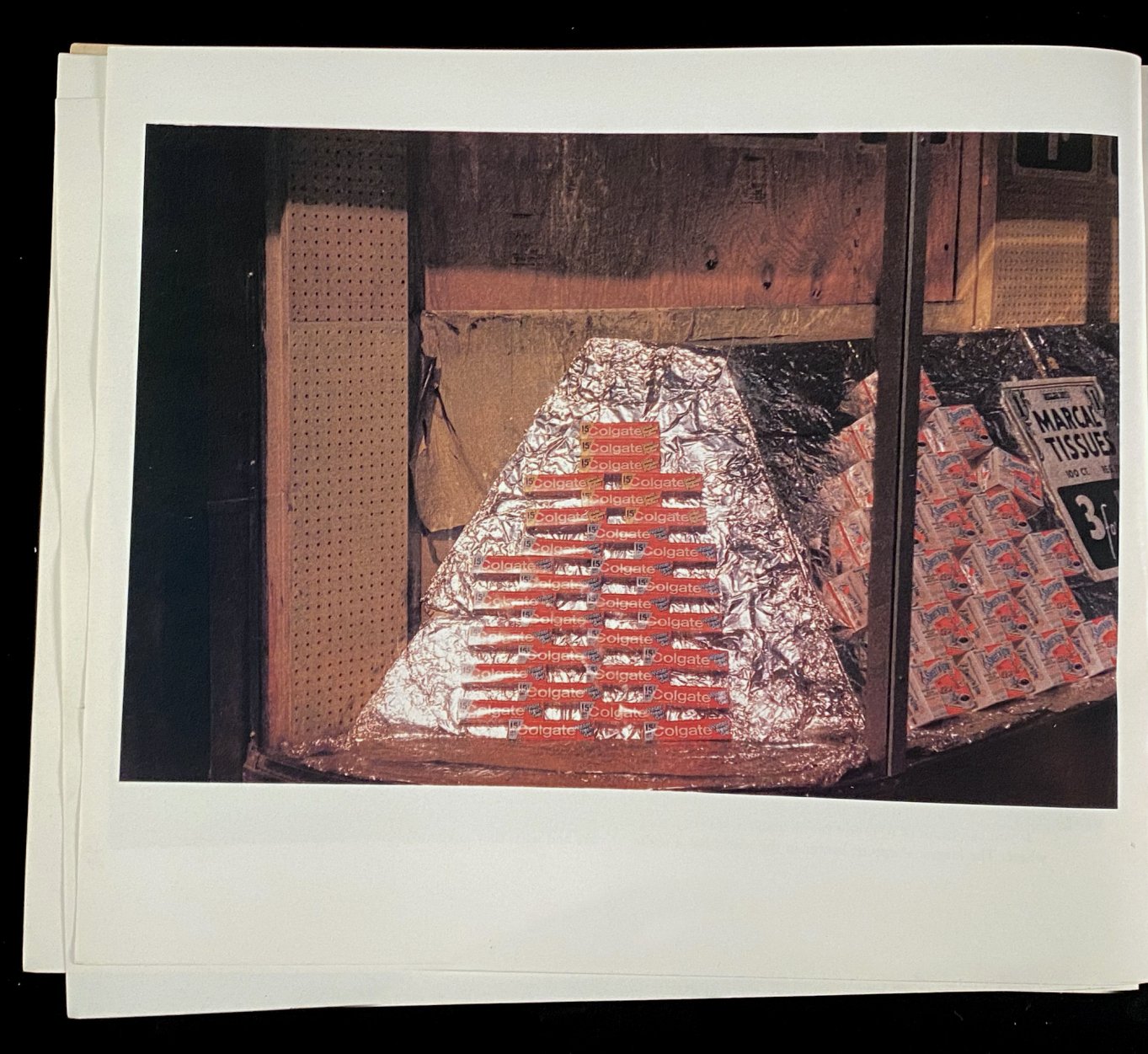

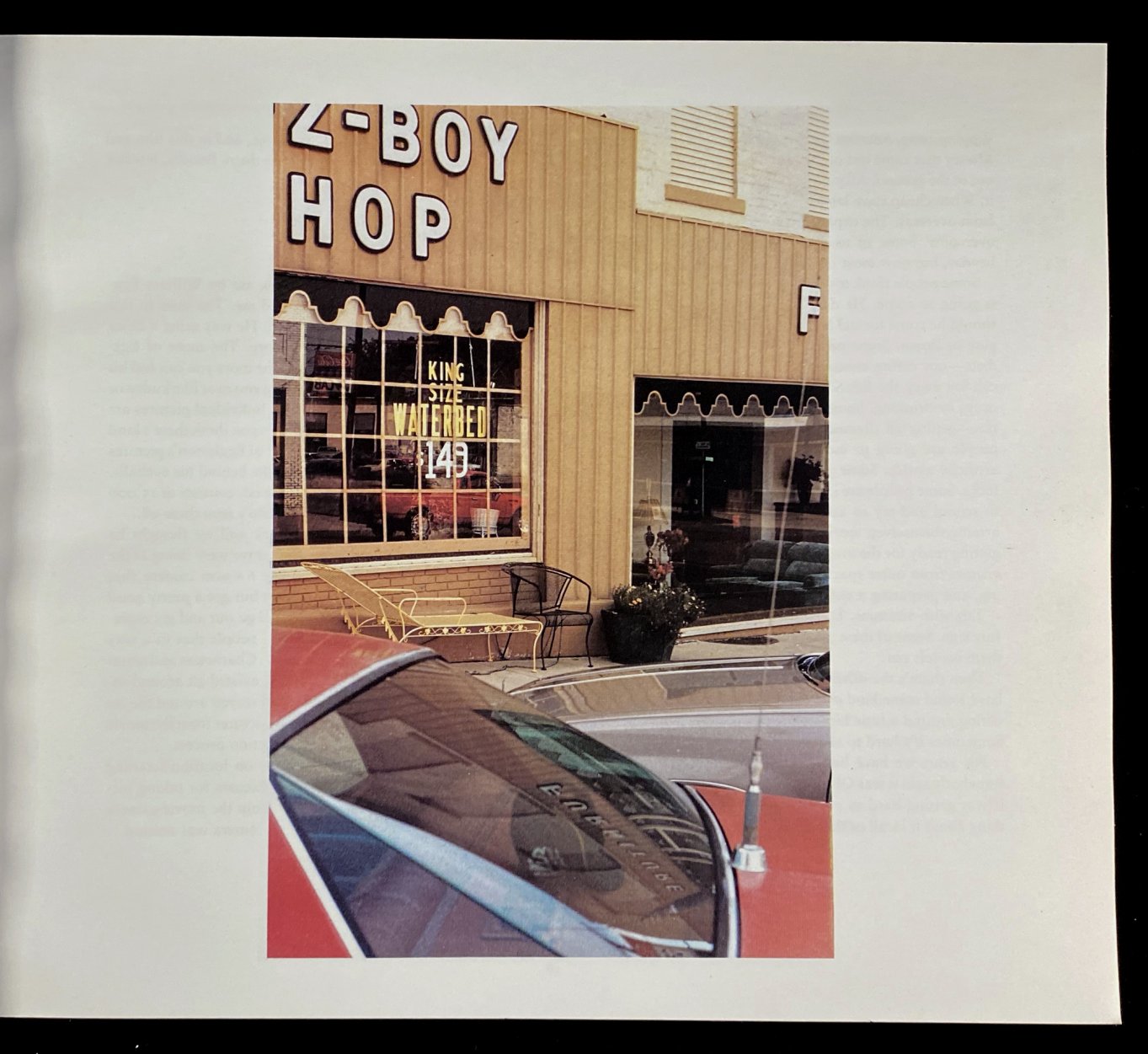

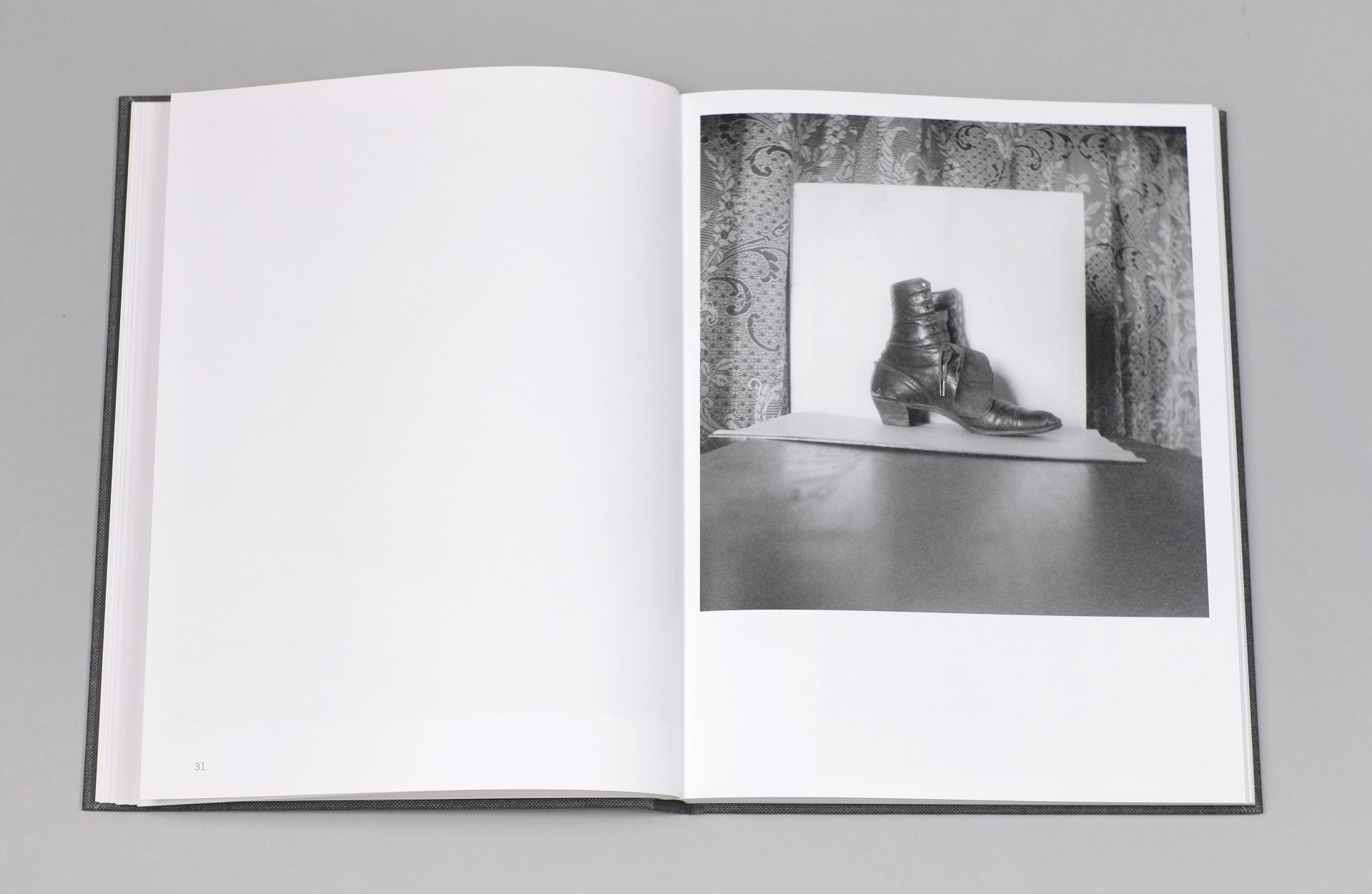

The ones in this introduction are by William Eggleston. He was using a Leica and buying his film in the drugstore. The more of Eggleston’s pictures you look at together, the more you can feel his sensibility and his way of looking taking you over like kudzu or some kind of insidious creeping moss. Individual pictures are sometimes hard to figure out. Sometimes you think there’s kind of nothing out there, but when you see a lot of Eggleston’s pictures at once you can feel what it must be like behind his eyeballs. His current project, The Democratic Forest, consists of 15,000 pictures. He’s probably the only one who’s seen them all.

Watch my YouTube review of various editions of The Democratic Forest:

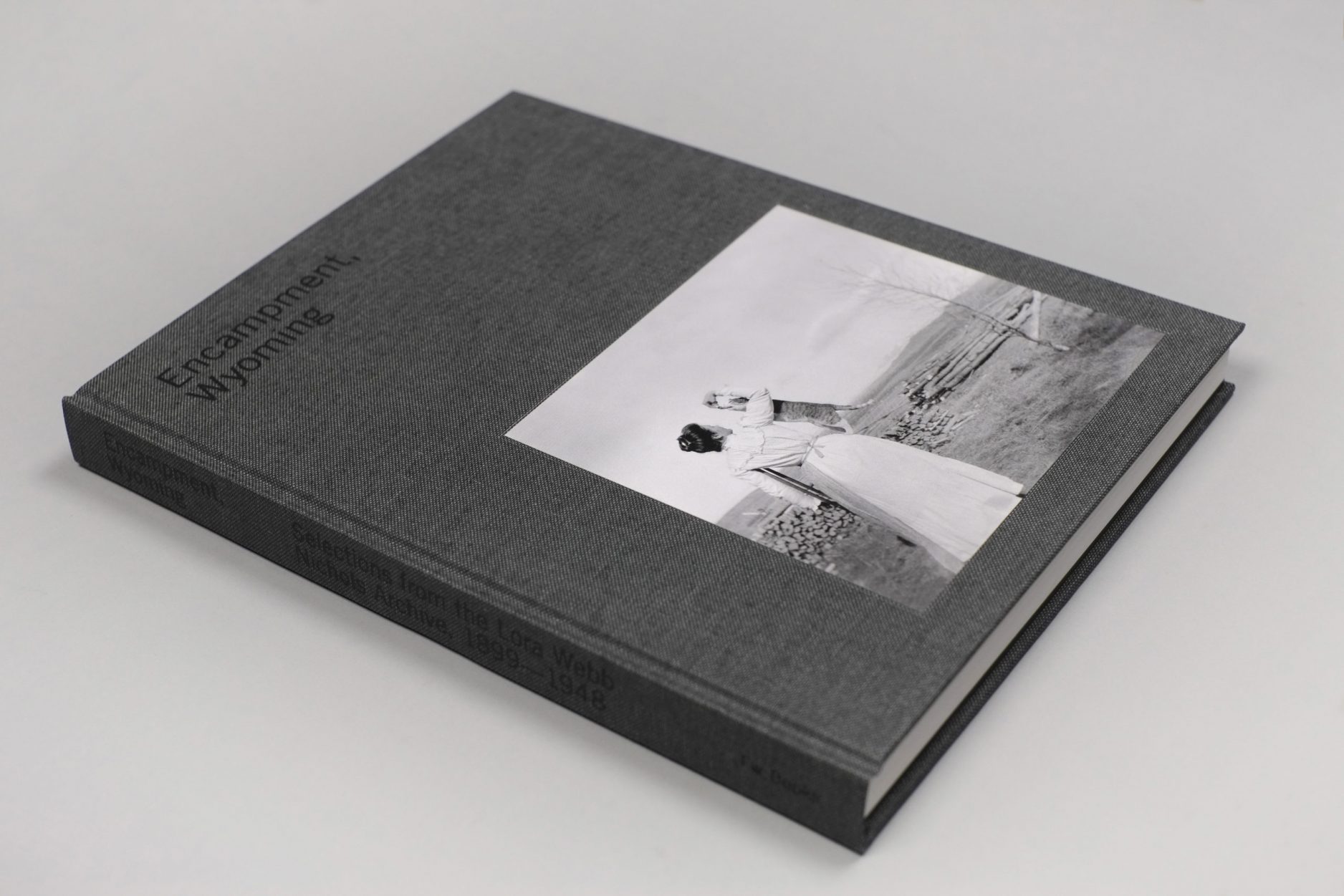

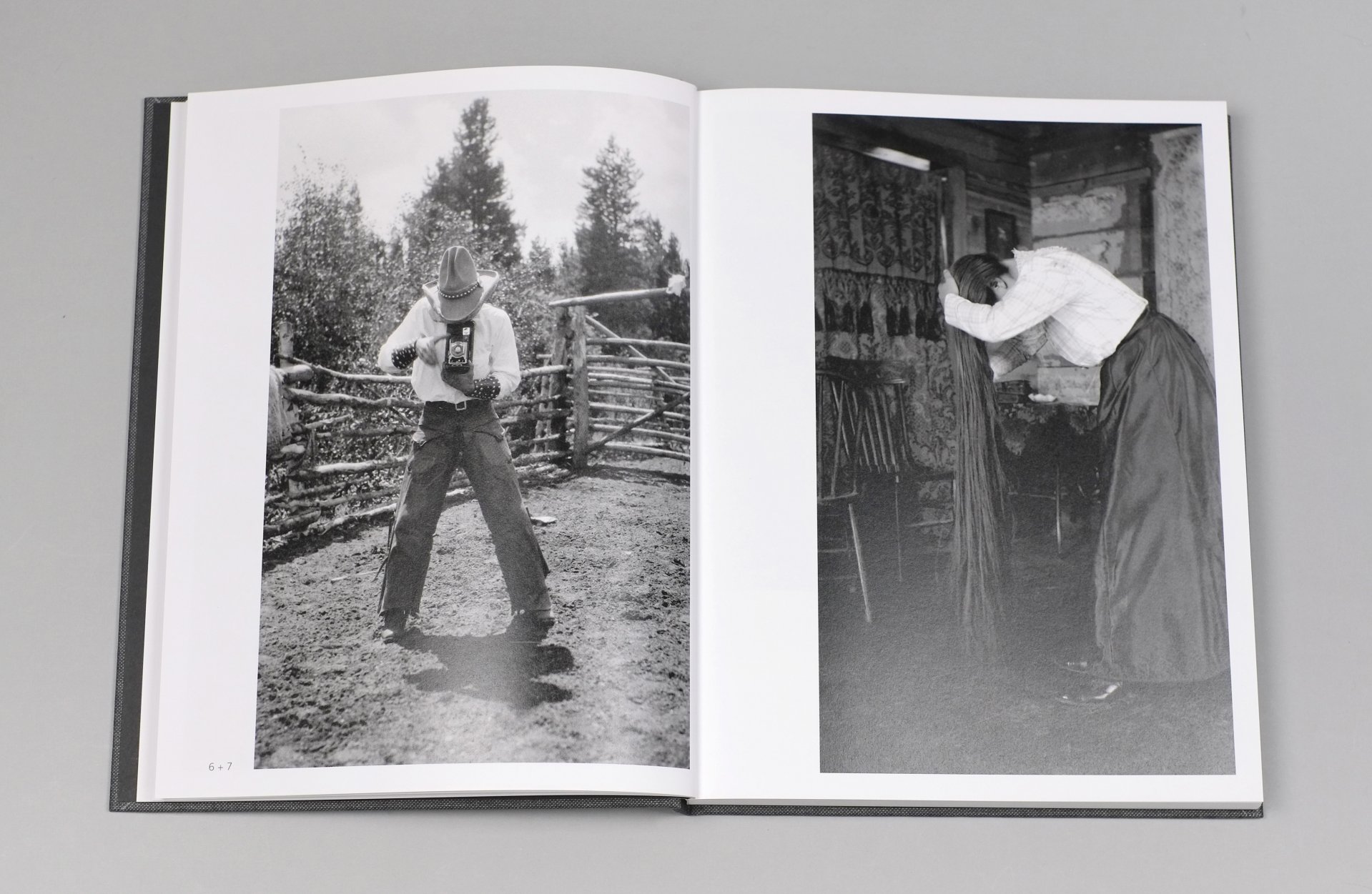

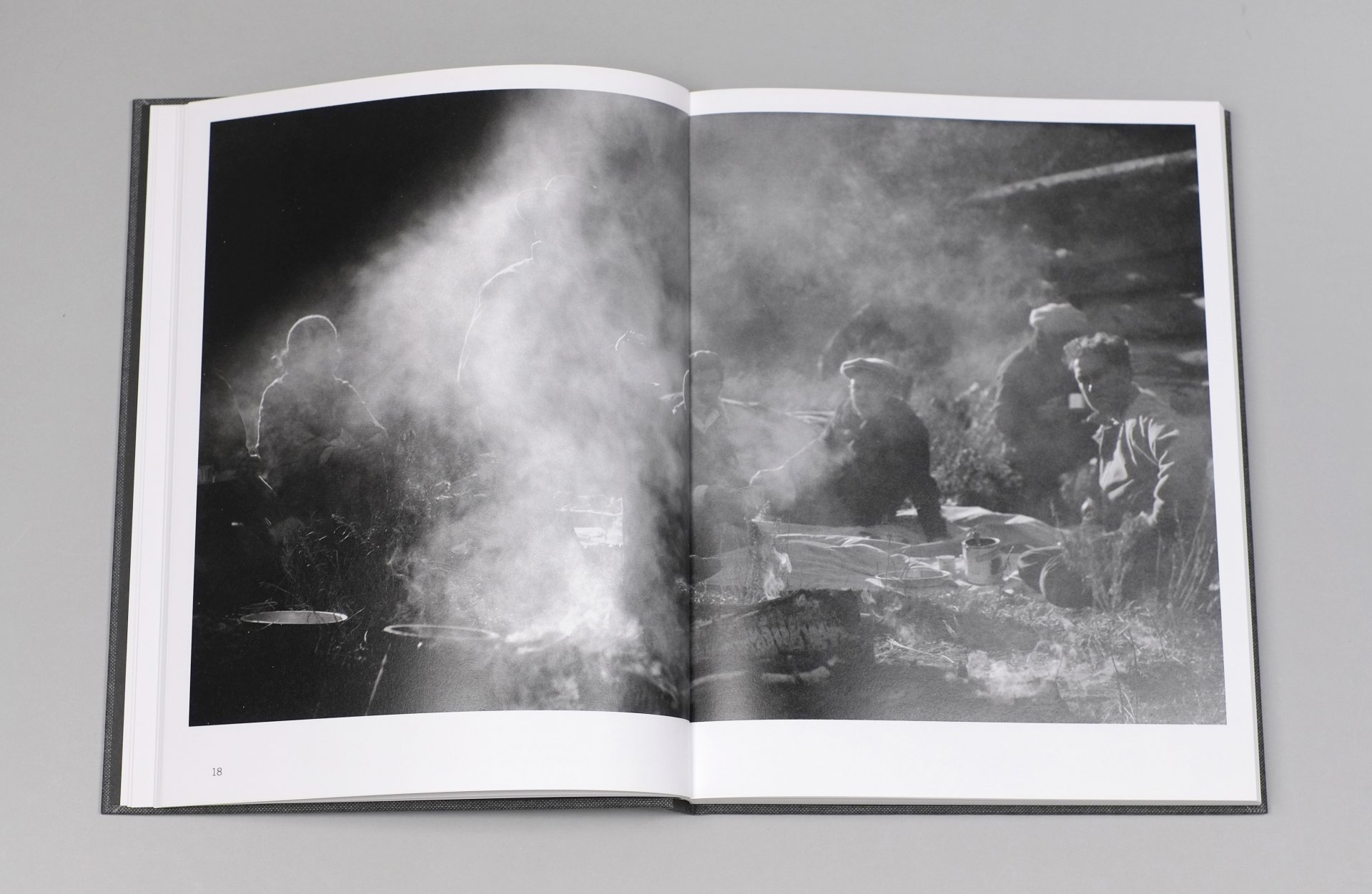

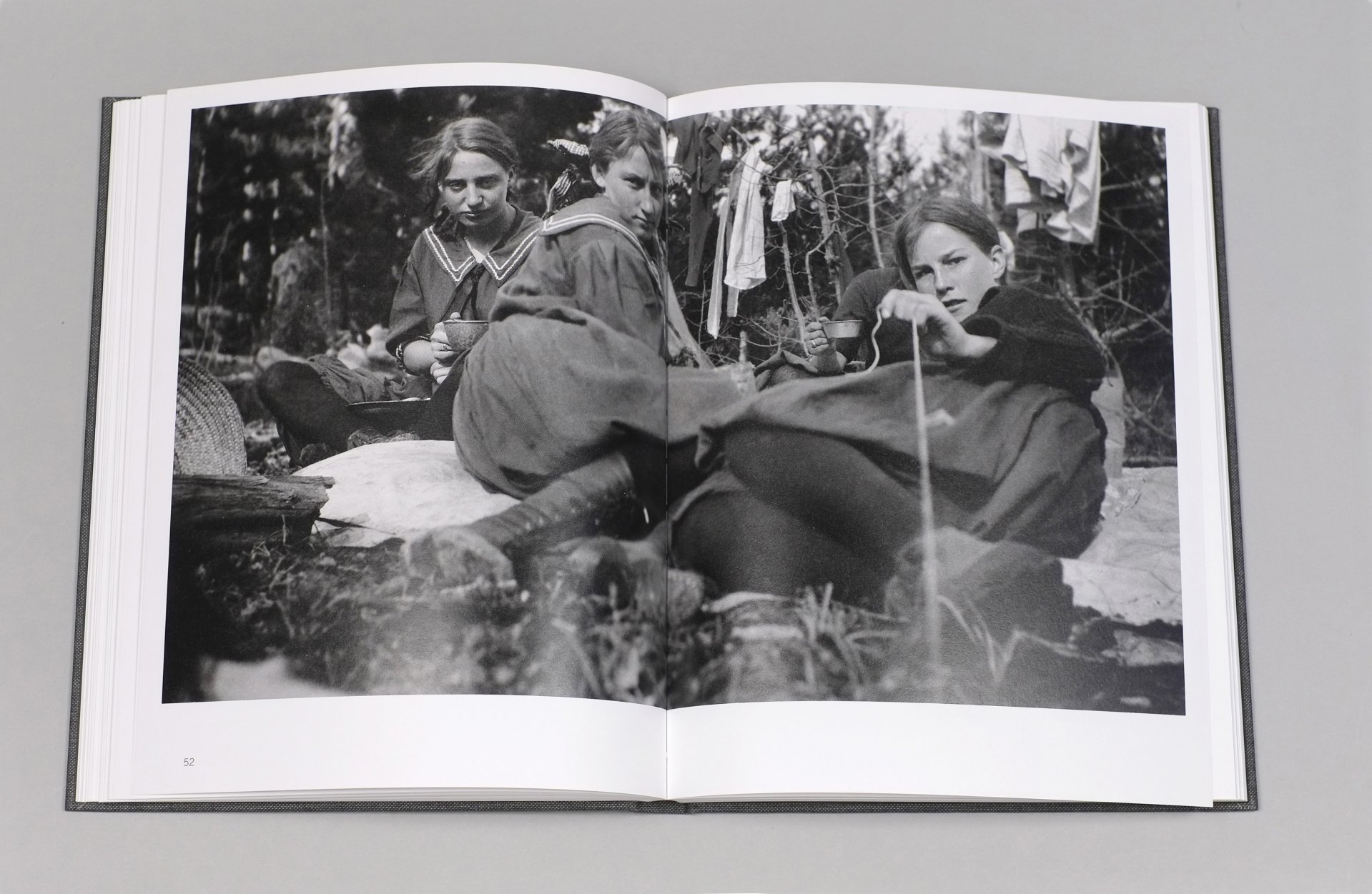

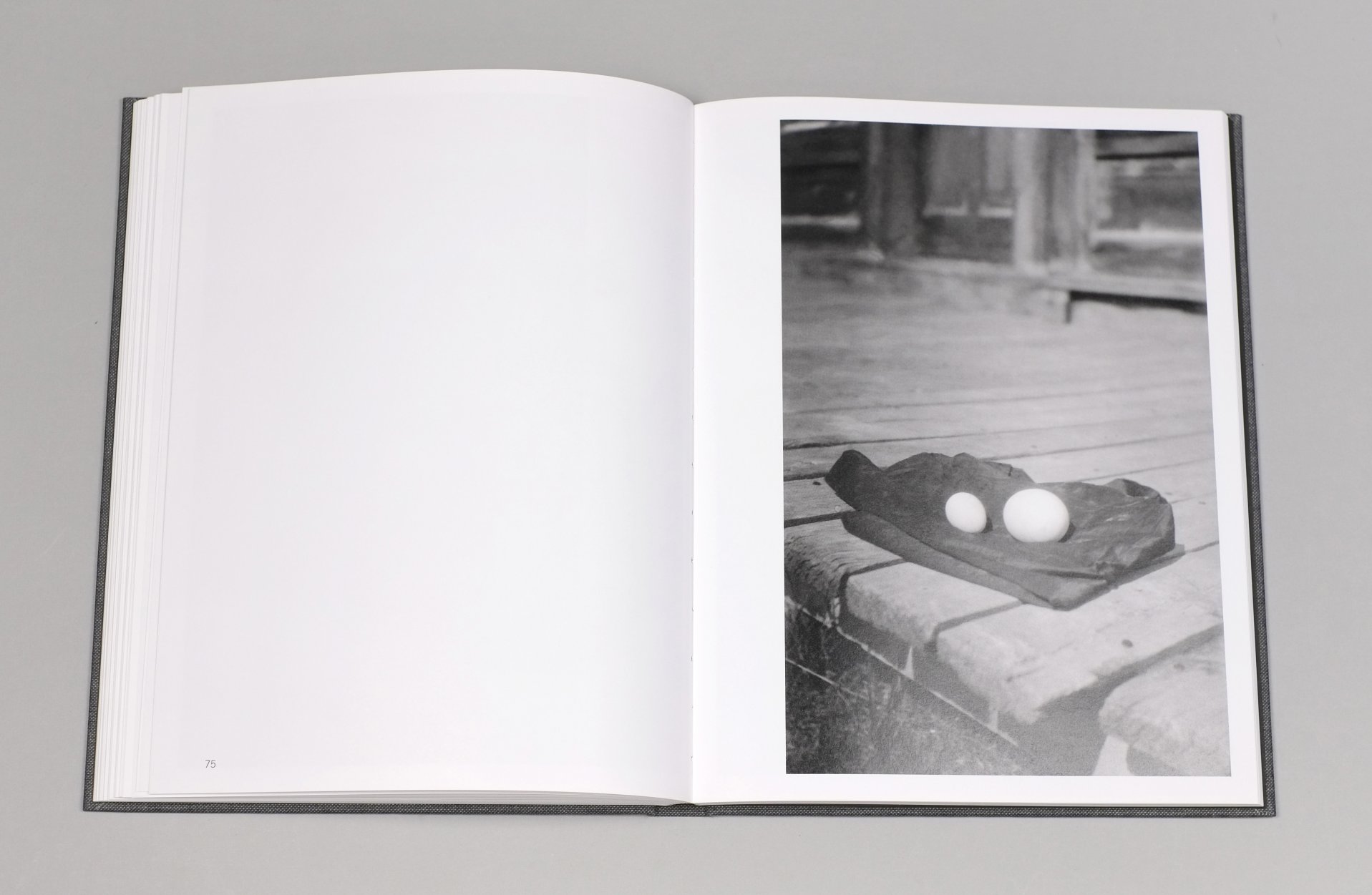

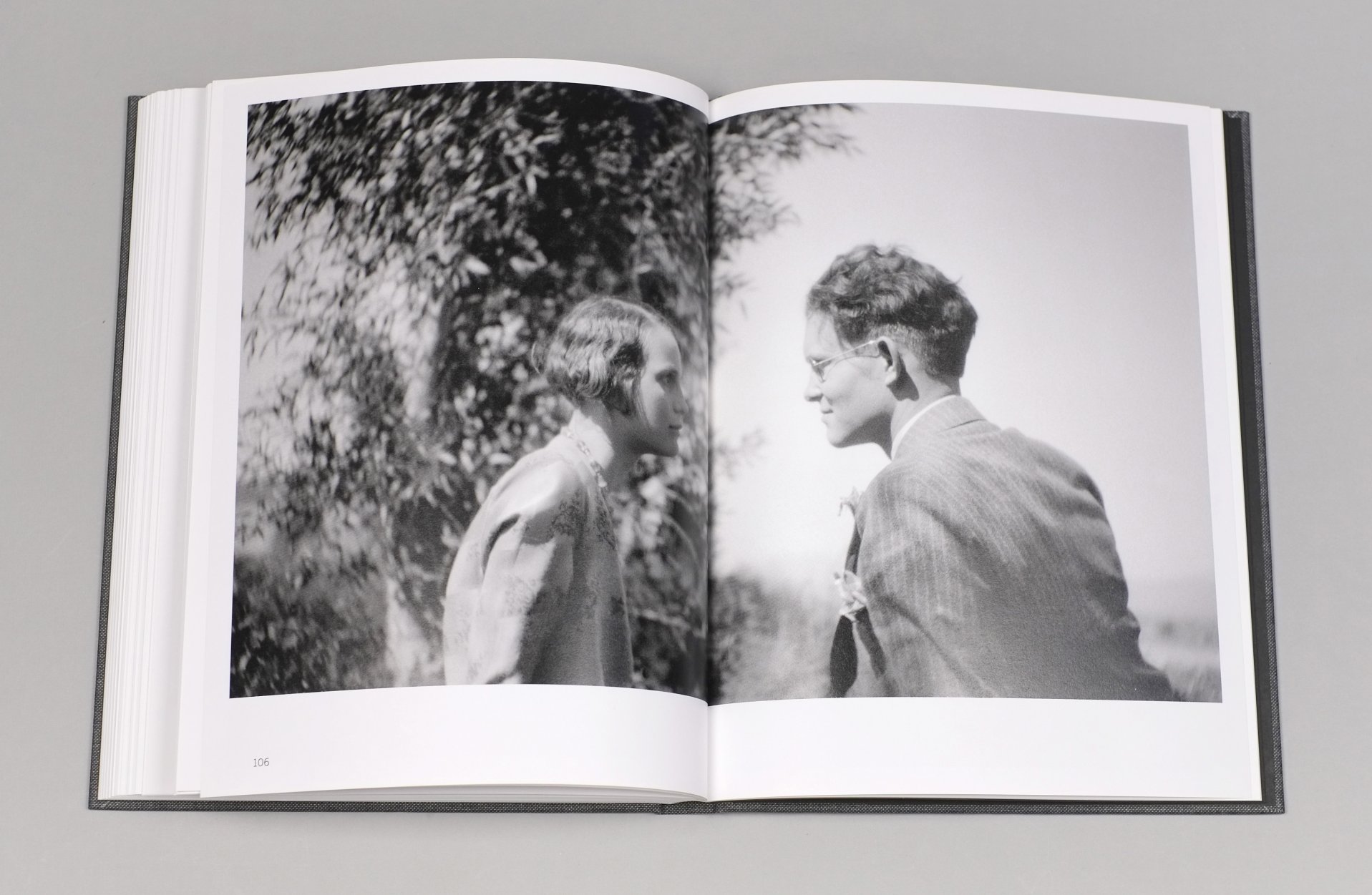

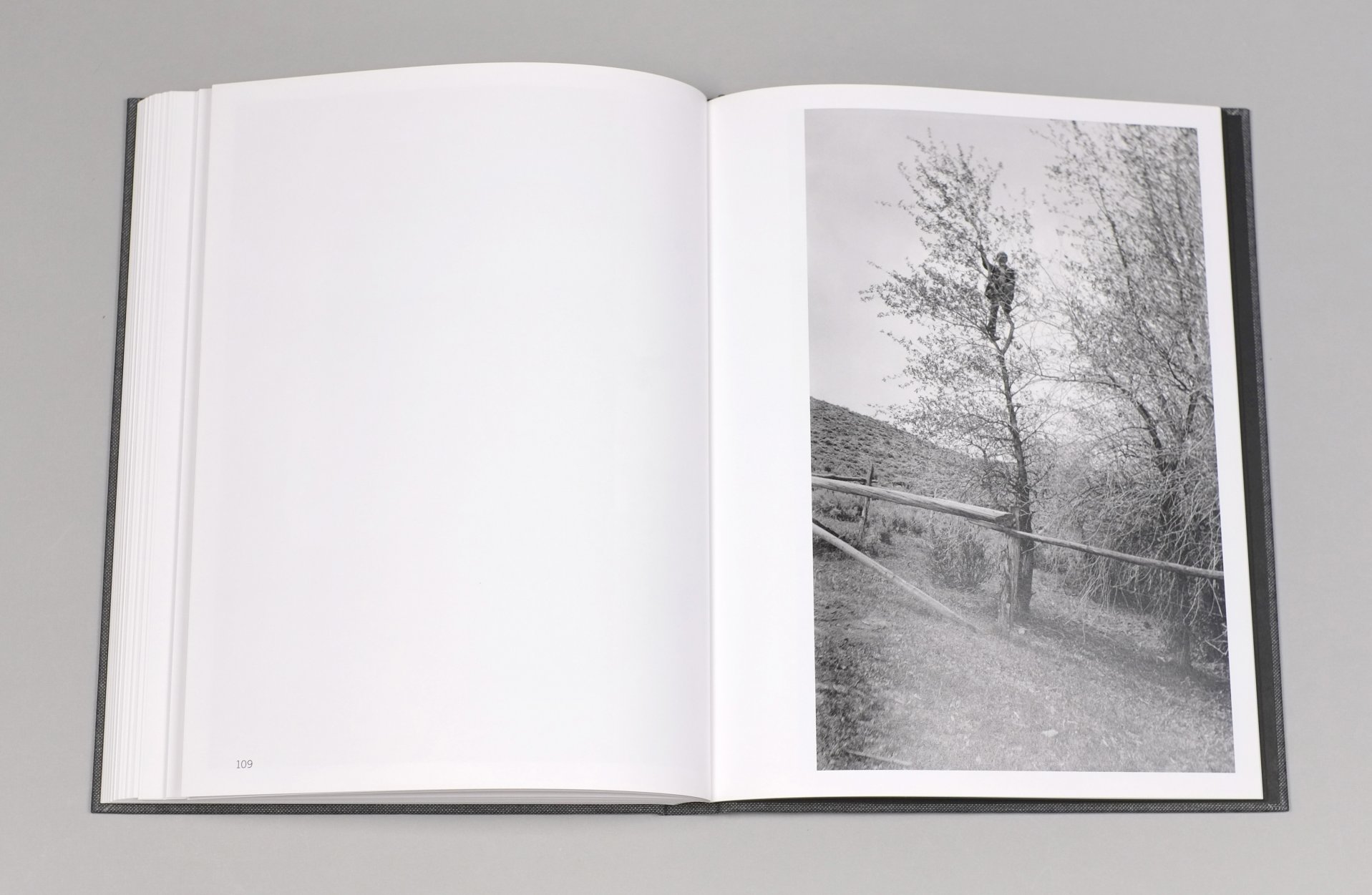

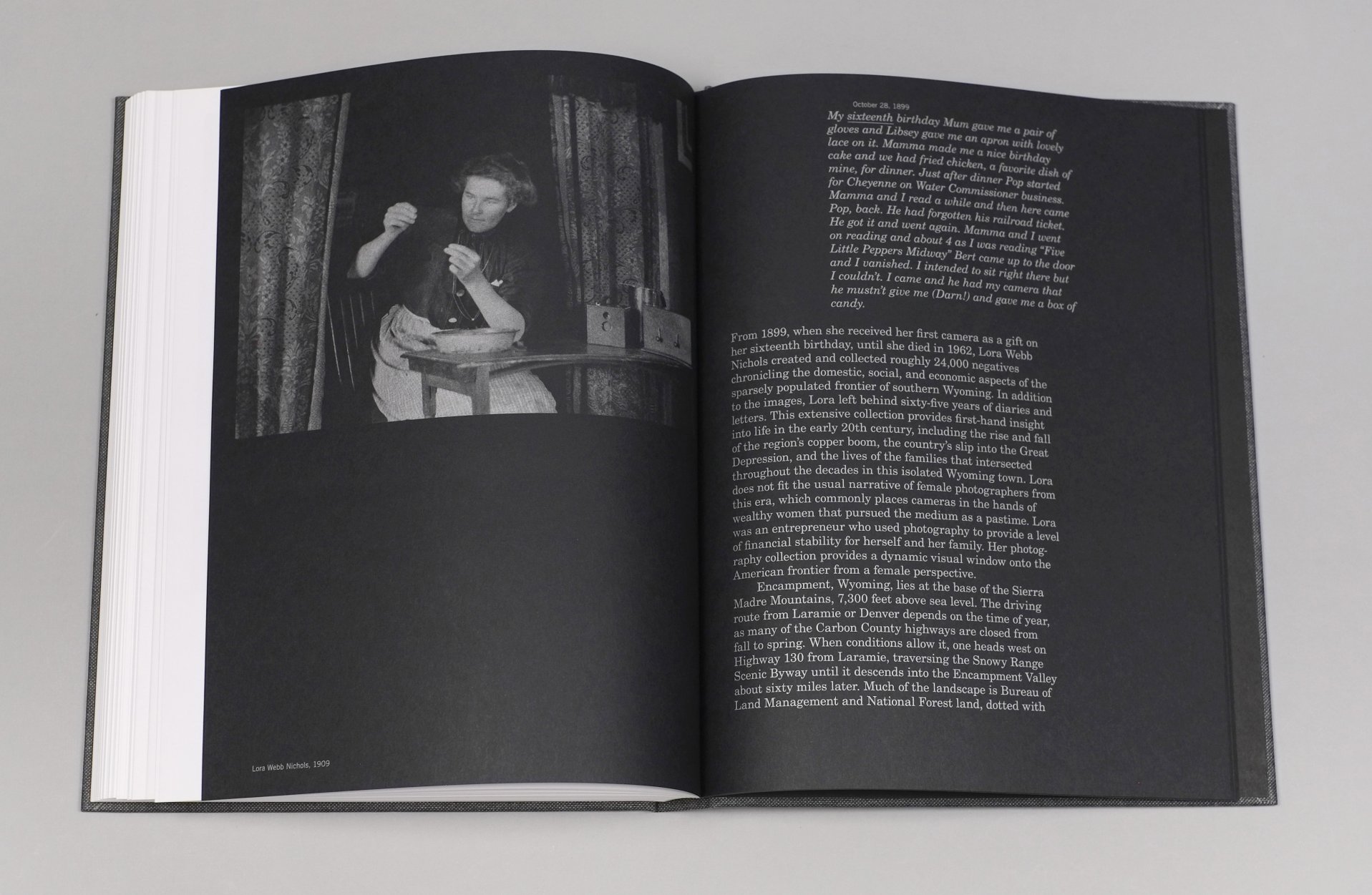

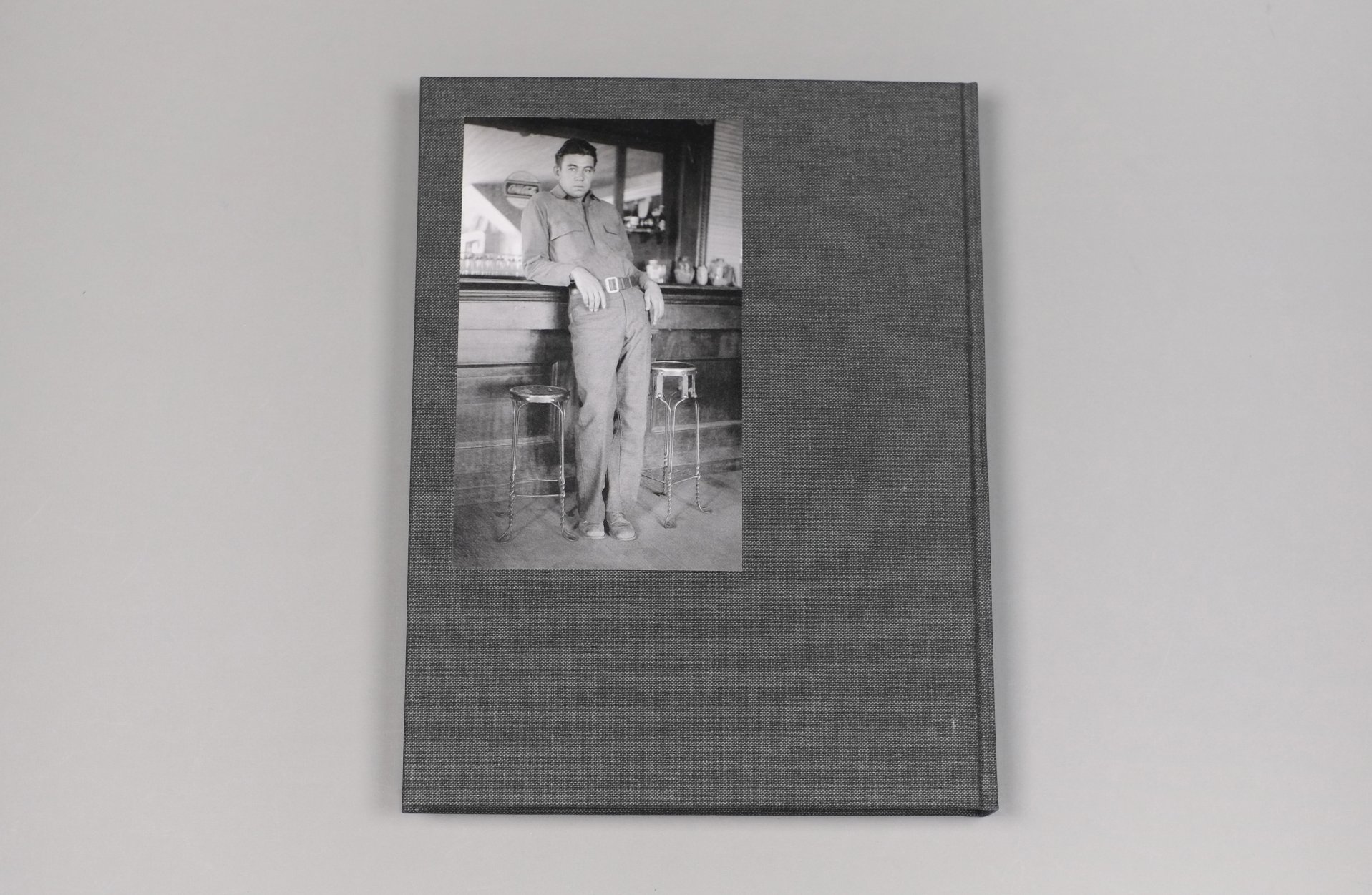

Recently Received: Encampment, Wyoming. Selections for the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948

From the moment she picked up a camera as a 16-year-old in the copper mining town of Encampment, Lora Webb Nichols’ pictures were as worthy of recognition as any others made in the 20th century. I like Mike Disfarmer as much as the next guy, but for me his pictures pale in comparison to Nichols’. A twice-divorced mother of five, Nichols shows us an intimate view of American life unlike any other I’ve ever seen. That Encampment, Wyoming represents less than one percent of her archive is astonishing, that it’s only coming to light now is infuriating.

As unfair as this is, Nichols is lucky to have Nicole Jean Hill as her champion. An artist, photographer and educator, Hill hasn’t just produced a historical document, she’s made a work of art. The bookcraft of Encampment, Wyoming is exceptional in every way, and the editing is as nuanced as best photographic literature. I’ve only owned Encampment, Wyoming for a few days, but it’s already one of my all-time favorites.

For more, watch my YouTube review of the book:

The Lunch Table:

Ethan: I recently watched American Animals, which was most interesting for its genre mixing approach. 7/10

Rylan: This week I read Journey of Souls by Michael Newton. It dives into the real life case studies of Newton’s patients undergoing hypnosis, and their experiences of living past lives. 7/10

Alec: I’ll watch anything with undercover cops. The Belgian series Undercover is better than most. 8/10